1

THE MISSING DIMENSIONS OF STATENESS

The state is an ancient human institution dating back some 10,000 years to the first agricultural societies that sprang up in Mesopotamia. In China a state with a highly trained bureaucracy has existed for thousands of years. In Europe the modern state, deploying large armies, taxation powers, and a centralized bureaucracy that could exercise sovereign authority over a large territory, is much more recent, dating back four or five hundred years to the consolidation of the French, Spanish, and Swedish monarchies. The rise of these states, with their ability to provide order, security, law, and property rights, was what made possible the rise of the modern economic world.

States have a wide variety of functions, for good and ill. The same coercive power that allows them to protect property rights and provide public safety also allows them to confiscate private property and abuse the rights of their citizens. The monopoly of legitimate power that states exercise allows individuals to escape what Hobbes labeled the “war of every man against every man” domestically but serves as the basis for conflict and war at an international level. The task of modern politics has been to tame the power of the state, to direct its activities toward ends regarded as legitimate by the people it serves, and to regularize the exercise of power under a rule of law.

Modern states in this sense are anything but universal. They did not exist at all in large parts of the world like sub-Saharan Africa before European colonialism. After World War II decolonization led to a flurry of state-building all over the developing world, which was successful in countries like India and China but which occurred in name only in many other parts of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. The last European empire to collapse—that of the former Soviet Union—initiated much the same process, with varying and often equally troubled results.

The problem of weak states and the need for state-building have thus existed for many years, but the September 11 attacks made them more obvious. Poverty is not the proximate cause of terrorism: The organizers of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on that date came from middle-class backgrounds and indeed were radicalized not in their native countries but in Western Europe. However, the attacks brought attention to a central problem for the West: The modern world offers a very attractive package, combining the material prosperity of market economies and the political and cultural freedom of liberal democracy. It is a package that very many people in the world want, as evidenced by the largely one-way flows of immigrants and refugees from less-developed to more-developed countries.

But the modernity of the liberal West is difficult to achieve for many societies around the world. While some countries in East Asia have made this transition successfully over the past two generations, others in the developing world have either been stuck or have actually regressed over this period. At issue is whether the institutions and values of the liberal West are indeed universal, or whether they represent, as Samuel Huntington (1996) would argue, merely the outgrowth of cultural habits of a certain part of the northern European world. The fact that Western governments and multilateral development agencies have not been able to provide much in terms of useful advice or help to developing countries undercuts the higher ends they seek to foster.

The Contested Role of the State

It is safe to say that politics in the twentieth century were heavily shaped by controversies over the appropriate size and strength of the state. The century began with a liberal world order presided over by the world’s leading liberal state, Great Britain. The scope of state activity was not terribly broad in Britain or any of the other leading European powers, outside of the military realm, and in the United States, it was even narrower. There were no income taxes, poverty programs, or food safety regulations. As the century proceeded through war, revolution, depression, and war again, that liberal world order crumbled, and the minimalist liberal state was replaced throughout much of the world by a much more highly centralized and active one.

One stream of development lead to what Friedrich and Brzezinski (1965) labeled the “totalitarian” state, which tried to abolish the whole of civil society and subordinate the remaining atomized individuals to its own political ends. The right-wing version of this experiment ended in 1945 with the defeat of Nazi Germany, while the left-wing version crumbled under the weight of its own contradictions when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.

The size, functions, and scope of the state increased in non-totalitarian countries as well, including virtually all democracies during the first three-quarters of the twentieth century. While state sectors at the beginning of the century consumed little more than 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in most Western European countries and the United States, they consumed nearly 50 percent (70 percent in the case of social democratic Sweden) by the 1980s.

This growth, and the inefficiencies and unanticipated consequences it produced, led to a vigorous counterreaction in the form of “Thatcherism” and “Reaganism.” The politics of the 1980s and 1990s were characterized by the reascendance of liberal ideas throughout much of the developed world, along with attempts to hold the line, if not reverse course, in terms of state-sector growth (Posner 1975). The collapse of the most extreme form of statism, communism, gave extra impetus to the movement to reduce the size of the state in noncommunist countries. Friedrich A. Hayek, who was pilloried at midcentury for suggesting that there was a connection between totalitarianism and the modern welfare state (Hayek 1956), saw his ideas taken much more seriously by the time of his death in 1992—not just in the political world, where conservative and center-right parties came to power, but in academia as well, where neoclassical economics gained enormously in prestige as the leading social science.

Reducing the size of the state sector was the dominant theme of policy during the critical years of the 1980s and early 1990s, when a wide variety of countries in the former communist world, Latin America, Asia, and Africa were emerging from authoritarian rule after what Huntington (1991) labeled the “third wave” of democratization. There was no question that the all-encompassing state sectors of the former communist world needed to be dramatically scaled back, but state bloat had infected many noncommunist developing countries as well. For example, the Mexican government’s share of GDP expanded from 21 percent in 1970 to 48 percent in 1982, and its fiscal deficit reached 17 percent of GDP, laying the groundwork for the debt crisis that emerged that year (Krueger 1993, 11). The state sectors of many sub-Saharan African countries engaged in activities like running large state-owned corporations and agricultural marketing boards that had negative effects on productivity (Bates 1981, 1983).

In response to these trends, the advice offered by international financial institutions (IFIs) like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, as well as by the U.S. government, emphasized a collection of measures intended to reduce the degree of state intervention in economic affairs—a package designated as the “Washington consensus” by one of its formulators (Williamson 1994) or as “neoliberalism” by its detractors in Latin America. The Washington consensus has been relentlessly attacked in the early twenty-first century, not just by antiglobalization protesters but also by academic critics with better credentials in economics (see Rodrik 1997; Stiglitz 2002).

In retrospect, there was nothing wrong with the Washington consensus per se: The state sectors of developing countries were in very many cases obstacles to growth and could only be fixed in the long run through economic liberalization. Rather, the problem was that although states needed to be cut back in certain areas, they needed to be simultaneously strengthened in others. The economists who promoted liberalizing economic reform understood this perfectly well in theory. But the relative emphasis in this period lay very heavily on the reduction of state activity, which could often be confused or deliberately misconstrued as an effort to cut back state capacity across the board. The state-building agenda, which was at least as important as the state-reducing one, was not given nearly as much thought or emphasis. The result was that liberalizing economic reform failed to deliver on its promise in many countries. In some countries, indeed, absence of a proper institutional framework left them worse off after liberalization than they would have been in its absence. The problem lay in a basic conceptual failure to unpack the different dimensions of stateness and to understand how they related to economic development.

Scope versus Strength

I begin the analysis of the role of the state in development by posing this question: Does the United States have a strong or weak state? One clear-cut answer is that given by Lipset (1995): American institutions are deliberately designed to weaken or limit the exercise of state power. The United States was born in a revolution against state authority, and the resulting antistatist political culture was expressed in constraints on state power like constitutional government with clear-cut protections for individual rights, the separation of powers, federalism, and so forth. Lipset points out that the American welfare state was established later and remains much more limited (e.g., no comprehensive health care system) than those of other developed democracies, that markets are much less regulated, and that the United States was in the forefront of rolling back its welfare state in the 1980s and 1990s.

On the other hand, there is another sense in which the American state is very strong. Max Weber (1946) defined the state as “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.” The essence of stateness is, in other words, enforcement: the ultimate ability to send someone with a uniform and a gun to force people to comply with the state’s laws. In this respect, the American state is extraordinarily strong: It has a plethora of enforcement agencies at federal, state, and local levels to enforce everything from traffic rules to commercial law to fundamental breaches of the Bill of Rights. Americans, for various complex reasons, are not a law-abiding people when compared to citizens of other developed democracies (Lipset 1990), but not for want of an extensive and often highly punitive criminal and civil justice system that deploys substantial enforcement powers.

The United States, in other words, has a system of limited government that has historically restricted the scope of state activity. Within that scope, its ability to create and enforce laws and policies is very strong. There is, of course, a great deal of justified cynicism on the part of many Americans about the efficiency and sensibility of their own government (see, for example, Howard 1996). But the American rule of law is the envy of much of the rest of the world: Those Americans who complain about how their local department of motor vehicles treats motorists should try getting a driver’s license or dealing with a traffic violation in Mexico City or Jakarta.

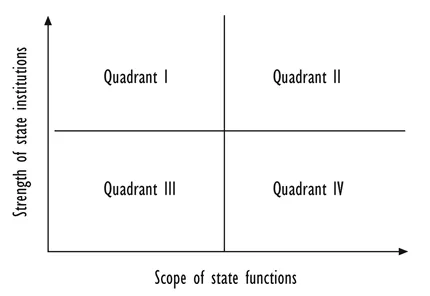

It therefore makes sense to distinguish between the scope of state activities, which refers to the different functions and goals taken on by governments, and the strength of state power, or the ability of states to plan and execute policies and to enforce laws cleanly and transparently—what is now commonly referred to as state or institutional capacity. One of the confusions in our understanding of stateness is that the word strength is often used indifferently to refer both to what is here labeled scope as well as to strength or capacity.

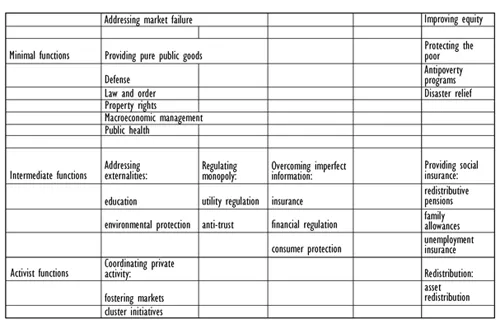

Distinguishing between these two dimensions of stateness allows us to create a matrix that helps differentiate the degrees of stateness in a variety of countries around the world. We can array the scope of state activities along a continuum that stretches from necessary and important to merely desirable to optional, and in certain cases counterproductive or even destructive. There is of course no agreed-on hierarchy of state functions, particularly when it comes to issues like redistribution and social policy. Most people would agree that there has to be some degree of hierarchy: States need to provide public order and defense from external invasion before they provide universal health insurance or free higher education. The World Bank’s 1997 World Development Report (World Bank 1997) provides one plausible list of state functions, divided into three categories that range from “minimal” to “intermediate” to “activist” (Figure 1). This list is obviously not exhaustive but provides useful benchmarks for state scope.

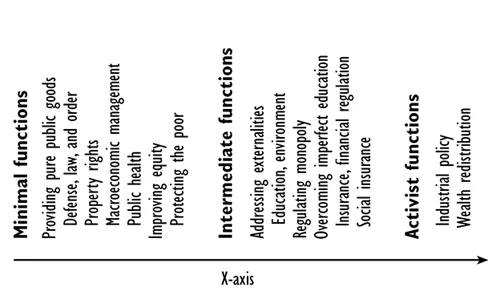

If we take these functions and array them along an X-axis as in Figure 2, we can then locate different countries at different points along the axis depending on how ambitious they are in terms of what their governments seek to accomplish. There are of course countries that attempt complex governance tasks like running parastatals or allocating investment credits, while being unable to provide basic public goods like law and order or public infrastructure. We will array countries along this axis according to the most ambitious types of functions they seek to perform.

There is a completely separate Y-axis, which represents the strength of institutional capabilities. Strength in this sense includes, as noted above, the ability to formulate and carry out policies and enact laws; to administrate efficiently and with a minimum of bureaucracy; to control graft, corruption, and bribery; to maintain a high level of transparency and accountability in government institutions; and, most important, to enforce laws.

Figure 1. Functions of the state. (Source: World Bank, World Development Report, 1997).

Figure 2. The scope of state functions.

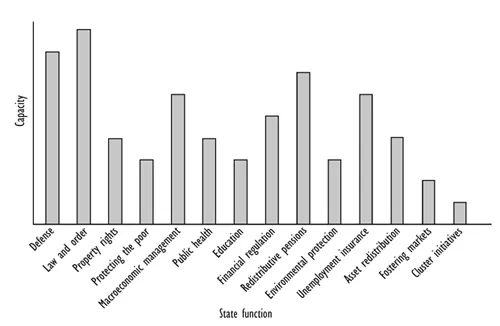

There is obviously no commonly accepted measure for strength of state institutions. Different state agencies may be located at different points along this axis. A country like Egypt, for example, has a very effective internal security apparatus and yet cannot execute simple tasks like processing visa applications or licensing small businesses efficiently (Singerman 1995). Other countries like Mexico and Argentina have been relatively successful in reforming certain state institutions like central banking but less so at controlling fiscal policy or providing high-quality public health or education. As a result, state capacity may vary strongly across state functions (Figure 3).

With the renewed emphasis on institutional quality in the 1990s, a number of relevant indices have been developed that help locate countries along the Y-axis. One of these is the Corruption Perception Index developed by Transparency International, which is based on survey data primarily from the business communities operating in different countries. Another is the privately produced International Country Risk Guide Numbers, which are broken down into separate measures of corruption, law and order, and bureaucratic quality. In addition, the World Bank has developed governance indicators covering 199 countries (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi 2003; indicators for six aspects of governance are available at www.worldbank.org/wbi/governance/govdata2002). There are also broader measures of political rights like Freedom House’s index of political freedom and civil liberties, which aggregates democracy and individual rights into a single guide number, and the Polity IV data on regime characteristics.1

Figure 3. State capacity (hypothetical).

Figure 4. Stateness and efficiency.

If we combine these two dimensions of scope and strength into a single graph, we get a matrix like that in Figure 4. The matrix divides neatly into four quadrants that have very different consequences for economic growth. From the economists’s standpoint, the optimal place to be is in quadrant I, which combines limited scope of state functions with strong institutional effectiveness. Economic growth will cease, of course, if a state moves too far toward the origin of the axis and fails to perform minimal functions like protecting property rights, but the presumption is that growth will fall as states move farther to the right along the X-axis.

Economic success is not, of course, the only reason for preferring a given scope of state functions; many Europeans argue that American-style efficiency comes at the price of social justice and that they are happy to be in quadrant II rather than quadrant I. On the other hand, the worst place to be in economic performance terms is in quadrant IV, where an ineffective state takes on an ambitious range of activities that it cannot perform well. Unfortunately, this is exactly where a large number of developing countries are found.

I have located a number of countries within this matrix for purposes of illustration (Figure 5). The United States, for example, has a less extensive state than either France or Japan; it has not attempted the management of broad sectoral transitions through credit allocation as Japan did in its industrial policy during the 1960s and 1970s, nor does it boast the same kind of high-quality top-level bureaucracy like France with its grands écoles. On the other hand, the quality of the U.S. bureaucracy is considerably higher than that of most developing countries...