![]()

One

PLACING WASHINGTON

Americans sort out their cities with nicknames and slogans. Faced with dozens of major metropolitan centers and scores of aspiring cities, we simplify the task of distinguishing Kalamazoo from Kokomo and Topeka from Tulsa by attaching shorthand characterizations. We traffic in common nicknames whether or not we have ever visited the Motor City, Baghdad by the Bay, the Emerald City (that's Seattle, not Oz), the Big Apple, or Big D. We look for truth in appellations and catchphrases that take on a life of their own. Perhaps the West really begins at Fort Worth. Could Boston truly be the hub of the American intellectual universe? Did Atlanta grow so fast because its white residents really were too busy to hate?

Nicknames and slogans are the products of self-conscious image making by civic elites and professional promoters. But they also catch the popular imagination when they appear to give plausible answers to common questions.1 What is life like there? Is it fast-paced, laid-back, artsy, businesslike? What does the place look like? Is it bathed in sunshine, washed by a mighty river, or crowded with bustling factories? What assumptions and values do residents share and emphasize? Are they tolerant, acquisitive, civic-minded, self-interested?

Sloganizing often ties a community specifically to its region. I grew up in Dayton, the Gem City of Ohio's Miami River Valley. For big events, like the first films photographed in Cinerama, we piled into the family Studebaker and drove fifty miles down the Dixie Highway (U.S. 25—the great connection between southern workers and middle western automobile factories) to the Queen City of the West, aka Cincinnati. Other names and slogans have tried and sometimes succeeded in identifying cities as the heart of Dixie, the capital of more than one inland empire, or the buckle of the Sunbelt.

In the midst of the urban babble, Washington, D.C., has been hard to pin down. As if the city is like one of its proverbial two-faced politicians, observers have struggled to capture its character in a single satisfying phrase or paragraph. John R Kennedy reflected this difficulty with his often-quoted aphorism that Washington is a city of “southern efficiency and northern charm.”2 Novelist Willie Morris reflected the same ambiguity in The Last of the Southern Girls (1973) when he created a Washington dinner party that seated Arkansas-bred Carol Templeton Hollywell next to a famous middle western writer:

“Have you ever written about Washington?” [she asks amid the clatter of china and silver].

“No” [is the writer's reply]. “Everybody's too native to somewhere else.”

“Northerners consider it Southern and Southerners think it Northern.”

“That's why it's here.”3

Morris's carefully crafted conversation is sharp writing but flawed analysis. It conflates two distinct approaches to understanding the essential Washington and blurs the fact that Americans tell two different stories about the character of their national capital. Aspects of these stories can be tested objectively, as I hope to do, but they have lives of their own. They are themselves cultural facts that help people make sense of an unusual place and give us entry points for thinking about cities, regions, and networks in the development of the nation.

The first story about Washington is a narrative of regional change. Washington used to be southern until. . . , or Washington is still southern despite This is the story that locals tell—journalists with Washington connections, congressmen with decades of Washington experience. It centers attention on the influx of outsiders and the influence of outside values that have supposedly changed the character of the city, but its timing is slippery. The turning point is sometimes put as far back as the Civil War or the Gilded Age. Others date the big change to World War I, or the New Deal, or World War II, or racial integration in the 1950s, or the New Frontier, or home rule in the 1970s, or globalization in the 1980s: “The sleepy Southern town that continued well into the 1970s has been replaced by a big-time city,” said a 1994 edition of a slick hotel room sights-and-shopping guide.4 Washington through this lens is regional but hard to focus, a southern city whose character seems to melt in the glare of television lights.

Gore Vidal's novel Washington, B.C. (1967), for example, describes such a process of regional change during the New Deal, when New York brain trusters and middle western graduate students arrived in numbers to rescue a ravaged economy through federal intervention. Vida's spokesperson is a fictional society columnist with Potomac Valley roots. Hosting a genteel party at a northern Virginia estate, she remarks that “our lovely, gracious Southern city has been engulfed by all these ... [she casts around for a tactful phrase] . . . charmin’ people who've opened our poor eyes to so many things undreamed of in our philosophy.”5 Vidal's character would have had a sympathetic ear in Mississippi senator John Stennis, who lamented in the 1970s about the slow erosion of Washington's traditionally “southern attitudes in the social realm—neighborliness, friendliness, conviviality.”6 Nevertheless, his colleague Mark Hatfield, arriving in Washington from Oregon in the late 1960s, was struck by the city's continuing southernness. Why, he wondered, did Washington's short-order cooks serve up his breakfast eggs and toast with what seemed to be a puddle of Cream of Wheat on the side of the plate?7

This story of southern retreat and staying power as retold by Vidal, Stennis, and scores of other observers is a direct attack on an essential truth. Washington was born in a regional borderland that was itself pulled among alternative futures at the start of the nineteenth century. For two hundred years the growing city has balanced between Tidewater and Piedmont, between East and West, and most obviously between North and South. Perceptions and images of its character have changed as the meanings ascribed to the nation's dominant regions have developed and changed. In the process of these larger changes, Washington has been enlisted on behalf of different groups, different agendas, and the different needs of South and North.

A second and very different understanding of Washington comes easily to many Americans who look at the city from the outside. This is a moral tale of sin and fall without redemption, telling of a community that has purchased power at the price of its soul and character. Its communities of bureaucrats and lobbyists are thought to make the city into an aberration that lacks the regional identification and loyalties that might be expected in more ordinary communities (“everybody's too native to somewhere else,” says Hollywell's dinner partner). Perhaps pandering to national prejudice, political leaders have frequendy criticized Washington as a city of outsiders and temporaries. “There are a number of things wrong with Washington,” said Dwight Eisenhower, himself the product of a peripatetic career; “one of them is that everyone has been too long away from home.” Richard Nixon, an extremely self-conscious outsider, agreed that “Washington is a city without identity. Everybody comes from someplace else. . . . Deep down, they still think they're back home.”8

The assumption of rootless residents implies that Washington cannot be understood as an identifiable place, but only as a collection of place seekers. To a newcomer like President Jimmy Carter, Washington was thus an “island” with few bridges to the American mainland. To journalist Joel Garreau, it is an aberration. Says one of the characters in Larry McMurtry's Washington-based novel Cadillac Jack (1982), “It's fine for spies and newspapermen, but it ain't everybody's cup of tea. Maybe you ought to move to Minnesota.”9

This second story is also true. Washington has been extraregional even as its society and politics have been intensely regionalized. The city originated as a platform for the federal government that would be outside the direct administrative control of a single state or set of states (although the choice and development of the site was never apolitical). Efforts to base economic growth on a local hinterland repeatedly failed. Instead, the seat of government slowly attracted national institutions and organizations—many of which now locate in Washington because of each other's presence, not because of the city's character as a special and specific place. The experts who operate these organizations come from a national pool of talent, not from the regional hinterland that supplies most middle managers in “real” cities like Milwaukee and Cleveland. Late-twentieth-century Washington is thus a node in national and global networks of power and communication.

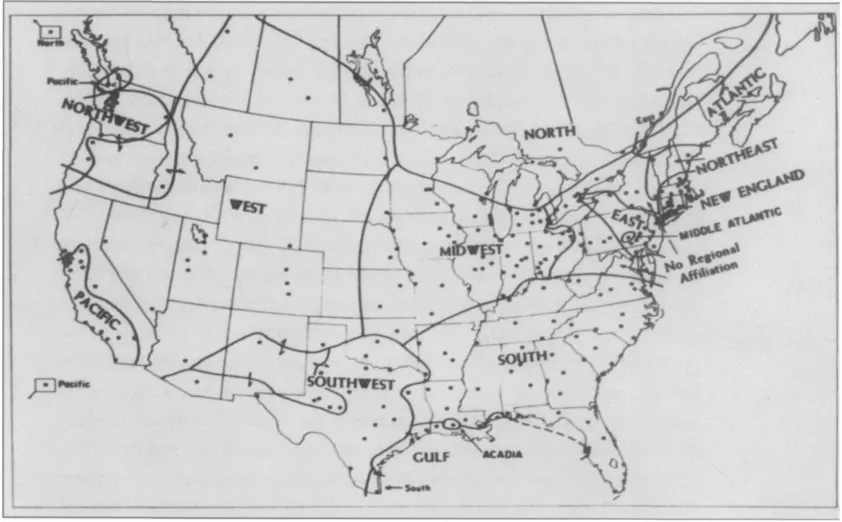

Washington and the zone of regional indifference. Geographer Wilbur Zelinsky found in the 1970s that Washington lay between areas of distinct regional identity but had no widely recognized regional identity of its own. (From Wilbur Zelinsky, “North America's Vernacular Regions,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 1980)

These contrasting ideas about Washington's character as a metropolitan community are the starting point for this essay in urban history. I want to remain close to the case—to the experience of Washington and Washingtonians—but also to use this fascinating city to explore the historical processes that have been involved in the construction and interaction of American regions and networks. As I have considered Washington's history, I have come to believe that it provides a valuable arena for analyzing the tensions between local or regional allegiances and global change. Rather than allowing theorists of the local and the general to talk past each other, we can benefit from research that uses a specific community to examine the tension between the local and the general, between horizontal and vertical pulls.

Washington, of course, is an extraordinary rather than a typical city, but it is unusual in ways that illuminate the interplay between place and network. Because it has had such an ambiguous and contested regional identity, its local character has been an item of open discussion rather than an unspoken assumption. Because it is embedded in national politics, its fitness for federal, national, and international activities has likewise been a subject of frequent debate. In Washington, in short, the social and political construction of place has been a public process.

First, to put the question in its most unsophisticated form, I want to know what regions Washington has “really” belonged to. If we slice the American map into North, South, East, West, and a myriad of smaller regions, where should we put Washington? How have regional influences worked themselves out in Washington over two centuries? Which regional characteristics and connections have faded, which have persisted, and which have been reconstituted?

Second, I want to know how extraregional connections have functioned in one of the nation's most intensely networked cities. Have they supplanted or supplemented regional ties? When and how did the “federal city” become a “national city,” and how have its national roles competed with those of other cities? How deeply can we trace the roots of its prominence as an international metropolis? And have these networked functions turned it into one of those artificially sustained “nonplaces” that critics of postmodernism so gleefully assail?10

A slightly different way to formulate the same questions is to ask where Washington has fit within a changing system of cities in the United States. What roles and functions have the city's leadership and the nation at large defined at different periods? How successfully has the city performed these roles? How have these roles differentiated it from neighboring or competing cities—first Alexandria and Georgetown, then Baltimore and Richmond, then New York and Atlanta? What have these developing roles meant for Washington's sense of itself as a community?

The pursuit of these specific historical questions inevitably engages theoretical discussions about the changing meaning and character of “place” or places in the modern and postmodern worlds. In developing this framework for analysis, we can think of Washington, and any other city, as pulled both “horizontally” among its neighboring regions and “vertically” from the local landscape to national and international roles.

An emphasis on regional connections and change raises empirical questions about the relative dynamism of different parts of the American nation. Because Washington is located in the border zone between two of the country's great cultural regions, much of its history is “mappable.” It can be represented in terms of competing pulls and influences among geographic regions that are spatially articulated and involve a “horizontal” dimension in urban development. The idea of Washington as a border or frontier city is a way to conceptualize this horizontal dimension.

The second formulation introduces a “vertical” dimension involving tensions between locally based connections and character and the influence of wide-ranging networks. It embeds Washington in the dialogue about the impacts of modernization and the changing scale of formal and informal institutions in industrial and postindustrial society. Modernization has involved the incorporation of specific places into national and international economic and social systems. It involves the triumph of bureaucracy over personal connections, long-distance affiliations over next-door neighbors, generalizability over particularity. In detail, Washington's modernization thus demonstrates the rise of large-scale institutions and challenges the assumption that local allegiances can persist in a globalizing world.

Involved in both horizontal and vertical dimensions is a tension between past and future, for a sense of history is embedded in our reading of regional character as well as our understanding of modernization. For the century from the 1860s to the 1960s, Americans usually read South as “old” and North as “new,” with Washington as a mediator between systems of values rooted in time as well as place. As well as anyone, Baltimore-born Karl Shapiro summarized this understanding in the opening lines of his 1942 poem “The Potomac”:

The thin Potomac scarcely moves But to divide Virginia from today.11

As these lines suggest, to talk about Washington's regional character is also to contribute to debates about the character of the American South. In different versions and understandings, the South is disappearing, enduring, or even extending its influence. To the degree that Washington has permanently shifted from “southern” to “northern,” its history suggests the inevitable erosion of a distinctively southern culture and society in face of national institutions and power. If Washington is best understood as an island and aberration, in contrast, the South by implication may be unaffected as a social and cultural region by the vast growth of a border metropolis. And if Washington is an arena in which southern connections are repeatedly revitalized, that experience offers evidence that the South itself remains a dynamic and lively region coequal with the North.

I assumed at the start of this project that I would be looking at nonpolitical Washington, paying little attention to the dynamics of federal power or to local government decisions. Instead, I find that everything about Washington is “political” in either a narrow or broad sense. Indeed, because of Washington's special symbolic and functional roles as the national metropolis, its identity repeatedly has been contested and redefined. Groups and factions within the United States have tried to use Washington to express and represent their own interests and values and to equate those values with the national interest. Regional claims on Washington have also been claims about the character of the nation.

At times these efforts have involved explicit contests for control of the ins...