![]()

Chapter One: A Classroon Revolution

The present is a period of transition. Old things are passing away and all things are becoming new.

—Frank A. Daniels, “New South,” University Monthly (April 1883)

The tiny market town of Wilson took on a carnival-like air in late June 1881. Up and down the main street, merchants and townspeople prepared for the opening of a new summer normal school for white teachers. The school lasted three weeks and attracted educators and visitors from surrounding towns and counties throughout eastern North Carolina. They came to see old friends, shop in Wilson’s stores, and take in the lectures of a distinguished faculty that included a British “teacher of elocution and oratory” and a professor of vocal music from Paris. Evening sessions offered “literary and musical entertainments,” most notably the exhibition of a “hand-painted Panorama of the Apocalyptic Vision of Saint John on the Isle of Patmos” and a series of stereopticon lectures on astronomy presented by Professor Sylvester Has-sell, the principal of a local academy. The normal school quenched local residents’ thirst for contact with a world beyond the solitude of scattered farms and commercial crossroads. By all accounts, it was the social event of the season.1

The normal school exercises might have proceeded uneventfully had it not been for a series of speeches delivered by Alexander Graham of Fay-etteville. Graham, who had taught for several years in New York State, brought news of the graded schools that were gaining popularity in the cities of the Northeast and in North Carolina’s larger towns. Unfortunately, there is no record of what he said, but his words must have been inspiring. White residents of Wilson gathered in a mass meeting on July 6 to make plans for joining the graded school movement. On a motion from the floor, B. S. Bronson, a local minister, was directed to compile a list of potential trustees and “to stir up a lively interest in the community on the subject.”2

At a second meeting, one week later, Bronson presented his nominees, all of them leading citizens: the clerk of superior court, an attorney, four merchants, three influential landholders, and a miller. Wilson township was then divided into districts, and canvasers were appointed to solicit support for a graded school in the form of voluntary subscriptions. By early August, the campaign was going well, and the county commissioners had agreed to give the trustees Wilson’s share of the public funds allotted for white education. The graded school opened on Monday, September 5, 1881, with five teachers and more than two hundred students organized into eight grades.3

Wilson’s new school became a major public attraction. People traveled from all across the state to see for themselves “the practical workings” of graded education. By June 1882, the town’s two thousand residents had hosted 8,291 curious guests. As many as one hundred visitors at a time crowded into the halls and classrooms on the busiest days. The Wilson graded school also attracted national attention when Amory Dwight Mayo, an educational evangelist from New England, came to inspect its operation. Mayo was so impressed that he prepared a special report for the Boston Journal of Education, encouraging his “Northern friends, travelling South . . . to stop and see the Wilson” experiment. “With no disposition to exaggerate,” he wrote, “we can honestly say we never saw so much good work done. . . . The children were there in force . . . and the enthusiasm of the youngsters over their work was something beautiful to behold.” But “the most interesting sight of all was the community in its relations to the new graded school. It had become the passion of the place; the sight to which the best people took their friends from abroad; the town-talk.” Mayo concluded by advising progressive communities across the South to send delegations of their “best men and women to bring home a report” on Wilson’s “model system of . . . instruction.”4

Why did the Wilson graded school stir such curiosity and excitement? After all, North Carolina had supported a system of public instruction since the 1840s. What was it about the graded school that so fired the imagination? To answer those questions, we must begin with the antebellum past and with the common schools that graded education aimed to replace.

On the eve of the Civil War, North Carolina was an economic backwater, known even among its own inhabitants as the “Rip Van Winkle State,” the “Ireland of America.” Lacking a major seaport and a system of easily navigable rivers, it never sustained great plantations like those boasted by its neighbors, South Carolina and Virginia. But the state’s fortunes were shaped nonetheless by the economics of slavery. Political power rested in the hands of eastern slave owners who held the great bulk of their wealth in the form of human rather than real property. Unlike land, that investment was movable, and its value bore little relation to local development. As a result, North Carolina’s governing elite gave scant attention to improving the countryside through the construction of railroads, canals, villages, and factories. They sought instead to maximize the return on their investment in slaves. When the soil wore out, planters—particularly those of more modest means—picked up and moved to unexploited land elsewhere in the state or to the fertile fields of Alabama, Mississippi, and western Tennessee. Between 1790 and 1860 that footloose behavior helped to drop North Carolina’s population from fourth to twelfth largest in the nation. Those planters who remained produced cotton, tobacco, and rice—crops that oriented them toward the coastal export trade rather than inland commerce. For that reason, they offered only limited support for efforts to pierce the state’s interior with plank roads and rail lines. Local investors and the state legislature financed a fledgling rail system on the coastal plain during the 1830s and 1840s, primarily to service the cotton and tobacco economy, but until 1856 no track extended farther west than Raleigh, the state capital, which lay just one hundred and fifty miles from the shore.5

Underdevelopment left most North Carolinians in the upcountry Piedmont and mountain regions living in rural isolation. Poor transportation hobbled commercial agriculture and reinforced a system of general farming and direct exchange among local producers. White yeomen and a smaller group of tenants raised corn, wheat, and other grains to feed their families; in the woods and meadows that surrounded their fields, they herded cattle and hogs, hunted wild game for the table, and harvested timber for fuel and shelter. People found dignity in working with their hands,

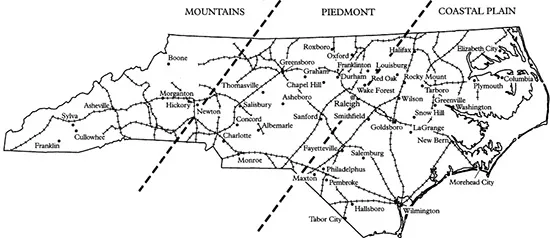

Map 1. North Carolina counties

Map 2. North Carolina railroads, cities, and towns, ca. 1894

treasured control over their labor, and considered ownership of land—or at least access to the means of subsistence—a common right. Although they were not unaware of events in the outside world, they grounded their identities in a familiar circle of family, neighbors, and friends. Calvin Henderson Wiley, who took office as the first state superintendent of common schools in 1852, thought of North Carolina as less a state than “a confederation of independent communities.” “Whoever travels over North Carolina,” he observed, “will meet with great apparent diversity of character, manners, and interest; and if he be much attached to the ways . . . of his own community, will hardly ever feel himself at home from the time that he crosses the boundaries of his county.” Nearly thirty years later, another traveler found most North Carolinians to be “independent and happy, but very far from the rest of the world.”6

The state’s common schools bore the stamp of that rural society. Before the mid-1880s education was primarily a local enterprise that served to integrate children into webs of personal relations defined by kinship, church, and race. North Carolina first provided for a system of public education in 1839, when lawmakers empowered individual counties to collect school taxes supplemented by payments from a state Literary Fund. This fund, established fourteen years earlier, drew its revenues from bank and navigation company stocks, taxes on auctioneers and distillers, and profits from the sale of state-owned swamplands and other public holdings. By the time of the Civil War, those resources supported the instruction of more than 100,000 children—roughly half the white school-aged population—enrolled in 3,488 districts scattered across the countryside.7

Under the Reconstruction Constitution of 1868, the benefits of schooling were extended to African American children, and a tax-supported, four-month term was made a legal requirement rather than a local option. Black Republicans fought for those provisions on behalf of constituents who viewed education as the key to realizing their dream of independence on the land. For the freedmen, illiteracy was both a badge of servitude and a serious liability in their dealings with white landlords and merchants. They embraced the common school as a means of putting “as great a distance between themselves and bondage as possible.” But in other fundamental ways, the antebellum system of public instruction survived relatively unaltered. In the years immediately after the Civil War, schooling in black and white communities alike continued to stand on what one observer described as a foundation of “home rule and self-government.”8

State law provided for an educational bureaucracy with only limited power. Throughout much of the mid-nineteenth century, politicians considered the state superintendency a “little office,” and its occupants labored under the constraints of a vague legal mandate to “direct the operations of the system of public schools.” Until 1885, the legislature refused even to supply a clerk to help the superintendent manage his correspondence. In the same year, lawmakers made provisions for the appointment of county boards of education and expanded the power of county superintendents to intervene in day-to-day schoolhouse affairs. But because board members served without pay and superintendents received only a modest per diem, few gave the work their full attention. In many counties, the superintendent never visited the schools in his charge. Meaningful authority remained largely in the hands of the three committeemen selected in each school district by the boards of education to oversee the hiring of teachers, the arrangement of the school calendar, and the disbursement of appropriated funds.9

The appointment of district committeemen reflected local hierarchies and served as an extension of the political process in which men vied for power, respect, and standing for themselves and their families. In Orange County, for example, Democrats used the school districts as basic units of political organization. During the spring, the party faithful in each district gathered to advise the county board of education on who should be named to the school committees and to select delegates to the party convention. Farther east, in counties with heavy black populations, the selection of district committees also reflected the politics of race. Under informal agreements with ruling Democrats, black community leaders often claimed at least one, and sometimes all three, of the committee posts attached to their neighborhood schools. White officeholders, mindful of the political clout of black voters, viewed such compromises as the price of power. While they retained ultimate authority over the allocation of school funds, they ceded to black parents a basic measure of day-to-day “control over their own schools.”10

District committeemen kept themselves well apprised of their neighbors’ opinions. Unless parents approved of a local committee’s actions, they would neither enroll their children nor help secure the land and supplies necessary for building and maintaining schoolhouses. Most common schools stood on private property and were constructed without direct state assistance. When a district needed a new school, local committeemen mobilized their neighbors to undertake the construction. J. M. White of Concord remembered how his community went about replacing a dilapidated log schoolhouse in 1883. The district committee “decided not to have any school one winter” and diverted the money that otherwise would have been used to hire a teacher into a special building fund. A carpenter in the neighborhood drew up plans for a new frame structure, and a generous farmer offered all the necessary “field pine timber,” provided that his neighbors agreed to “come with wagons and hands to chop and haul.” The families then passed the hat to collect extra money for shingles, nails, and homemade desks. On the appointed day, men and boys gathered early in the morning to assist the carpenter, while the women prepared hot meals for all who joined in the task. In the evening, the neighbors celebrated their accomplishment and congratulated themselves on building “the best country schoolhouse in Cabarrus county.”11

Perhaps justified in this case, such pride more often belied the conditions under which children learned their lessons. One student described her school as a “very common” structure “situated in the woods nearly half a mile from the public road. When it rains the yard is covered with water and is very muddy. The house is not plastered and there are some very large cracks all about.” At another school, a young teacher found “nothing . . . to absolutely repel one, but . . . equally as little to attract.” The walls, “which had once been white,” were “ornamented by the hieroglyphics of incipient pensmen” and “smoked almost to blackness” by misuse of the fireplace. A “scratched and shabby-looking blackboard” stood at the front of the room, flanked by rows of “heavy, clumsy desks, so awkwardly constructed as more to resemble a contrivance for punishment than a comfortable seat for the ‘human form divine.’” Still other teachers were terrified by the snakes that coiled around schoolhouse rafters or entertained by the lizards that crawled in and out of the walls, feasting on flies.12

Nevertheless, the neighborhood school both shaped and reflected a sense of community. If the families in a district got along, the school expressed their harmony. If they were at odds, it fell prey to partisan bickering. According to the state superintendent, people in some neighborhoods could “get up more enmity, hatred, and raise a bigger row in general, over the public schools . . . than could be stirred up upon any other subject in the world, except politics.”13

In fact, conflicting political loyalties often provoked “public school wrangle [s].” W. D. Glenn, a dry goods merchant in a Gaston County settlement known as Crowder’s Creek, charged that “under Radical rule” he and his Democratic neighbors in school district number 47 had been “robbed” by Republicans in district number 50, who had redrawn the boundary lines and claimed a mile of their territory. The expropriation caused little trouble until the mid-18 80s, when the residents of the Republican district built a schoolhouse in the disputed area and, according to Glenn, “seduced our people to go to their school.” Since most of the county educational fund was distributed on a per capita basis, Glenn and his neighbors received only $70, compared to their rivals’ $100. Glenn’s faction convinced the Democratic school board to restore the old boundary, but they had less success with the defectors, who continued to send their children to the Republican school. Apparently, they had not been seduced after all. “Some of these live 1/4 mile some about 1/2 mile inside our district,” Glenn complained to state superintendent Sidney Finger. “Can a man belong where he pleases and go where he pleases across the dist[rict] line. What is a line for if they...