![]()

Part I: In the Shadow of Cotton

From now on, I am not responsible for defending and controlling this province that has been placed under my protection.

—Governor Antonio Martínez, 1820

![]()

Chapter One: The Texas Borderlands on the Eve of Mexican Independence

During the night of July 4, 1819, a soft rain began falling north of San Antonio, beating the parched earth with an endless stream of desperately needed water. A severe drought had seared the region for the past several years, burning away vast swaths of native grasslands and decimating herds of bison and wild cattle. Fields withered by the sun that summer had been unable to support the corn crops needed to sustain the Spaniards huddled in San Antonio, leaving the village gravely short of food. Even the horses were starving, with the Spaniards’ mounts so malnourished that some could barely stand. Yet the rain had finally come. Rolling across the burned ground, water began to fill the dried creek beds and arroyos that twisted their way southward. Eventually the storm made its way to San Antonio. For those who lived in that small, parched village, the din of rain on their rooftops surely sounded like mercy sent from the heavens.

San Antonio was a town in need of divine grace. Founded in 1718, a little more than a century earlier, the town sat on a stretch of land between the San Antonio River on the east and the San Pedro Creek on the west. Growing in spurts over the course of the eighteenth century, the village served as the makeshift capital of Texas, the most remote province along New Spain’s far-northeastern frontier. Despite its political status, the village had always languished in isolation as Spanish authorities refused to put significant resources into the region, sending only as few troops and supplies as necessary to keep alive their military presence in Texas. When the governor of Texas filed a report on the region in 1803, his assessment of San Antonio was grim. The village had, he lamented, “absolutely no commerce or industry” to support its modest population of twenty-five hundred, and were it not for a handful of hunters providing the town with buffalo meat, “the greater portion of the families would perish in misery.”1

If the village failed to prosper during the eighteenth century, it had been ravaged during the nineteenth. When the Mexican War for Independence broke out during the early nineteenth century, rebels captured the town in 1813 and executed the governor. Spanish authorities, in retaliation, launched a bloody military campaign to reclaim the region, killing hundreds of suspected rebels in San Antonio and sending hundreds more fleeing into the countryside. Those who survived the vicious reassertion of Spanish authority found themselves, in the years since, living under siege. Emboldened by the weakness of San Antonio, Comanches and Apaches launched an endless series of raids that bled the Spaniards of what few horses, cattle, and crops they still had. Wars, drought, and famine reduced the population of San Antonio to a mere sixteen hundred by 1819, almost a thousand fewer than lived there only two decades before.2

On that July evening in 1819, however, the rains had finally come. And they continued overnight, though too quickly for the drought-hardened ground. Shallow creek beds soon began funneling a torrential gush into the San Antonio River, which picked up speed and force as it moved south toward the village. By dawn, the river was straining at its banks. A wall of water broke into the north side of San Antonio just after daybreak, rushing through the streets with frightening momentum. The only bridge spanning the river cracked and shattered under the power of the rising tide. Water continued to force its way into the town, drowning every street and plaza, before finally joining the San Pedro Creek on the far-western side of San Antonio. Almost as soon as the flood began, there was no longer a town—only a wide, angry river that subsumed everything.3

The governor, Antonio Martínez, awoke to water pouring into his home. Wading out into the flooded streets, the aged patriarch could hardly comprehend the scene. Every avenue had been transformed into a furious river sweeping away screaming men and women who flailed about in desperate attempts to pull themselves to safety. Those lucky enough to snag tree limbs climbed high into the branches seeking refuge. Others tore off their clothes to keep from being pulled to their deaths beneath the water. The raging tide even unmoored homes from their foundations. Poorer families in San Antonio lived in rickety wooden huts, known as jacals, built of timber plastered together with mud and clay. Martínez watched, powerless, as the flood ripped apart jacals, often with families inside, and “houses began to disappear, leaving only fragments afloat to indicate the disaster that overtook them.”4

The governor ordered his soldiers to pull anyone they could from the water, sending the best swimmers to rescue people who had taken refuge in treetops. As the deluge continued, Martínez decided to abandon the town before the water rose any higher. Ordering all survivors to follow him, Martínez led a march toward the hills outside San Antonio, where they huddled beneath trees. Then, as quickly as they had come, the flood waters began to recede.

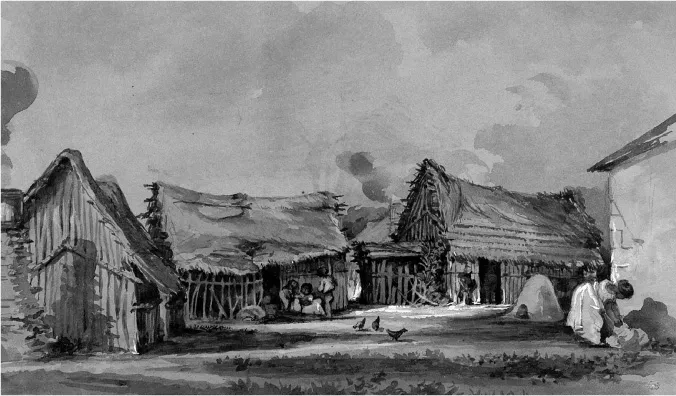

Mexican Huts, by James Gilchrist Benton, 1852. Most Tejanos in San Antonio lived in rickety jacals, many of which were swept away and destroyed by the 1819 flood. (Amon Carter Museum of American Art Archives, Fort Worth, Texas)

When they returned, the survivors surveyed the destruction. San Antonio in 1819 was divided into four neighborhoods that corresponded roughly to the directions on a compass.5 The northern and southern neighborhoods—where the wealthiest and most influential families lived—had been completely inundated, with homes and buildings near the town’s center sustaining the worst damage. The flood, however, had concentrated its fury on the poorer neighborhoods on the eastern and western sides of town. Raging waters had slammed hardest into the eastern neighborhood of Valero, where nearly every home had been a rickety jacal. Hardly a structure survived, as the flooding destroyed and killed indiscriminately. In the small western neighborhood of Laredo, the water rose so quickly that people, trapped within their homes, lashed together makeshift rafts in a desperate bid to avoid drowning. Many had not succeeded, and most of those who died in the flood came from either Valero or Laredo.

Governor Martínez returned to his residence on the east side of the military plaza, near the center of town. The receding waters swept away many of the governor’s household effects, and extensive damage made the home uninhabitable. Most other government buildings met similar fates. The royal corrals had been ruined, and the livestock lost. Storehouses of corn had flooded, spoiling what little food reserves the town had. There would now be no harvest that year—the fields just outside the village had been leveled. Like the governor, most residents had either been made homeless or lost their few possessions to the raging waters. Many no longer had clothes, having shed them to keep afloat during the height of the flood. No one could even be sure how many had died, and for days survivors toiled at the grim task of recovering the dozens of bodies that washed up on the riverbanks downstream.6

Three days after the flood, Martínez wrote two reports of the disaster, one for the commandant general in Monterrey, Nuevo León, the other for the viceroy of New Spain in Mexico City. Martínez described, in frank and brutal terms, the desolate scene in San Antonio, begging both men to send whatever aid might be possible to salvage the town. Martínez also brooded on the dark irony of a flood ravaging the same village that had prayed for an end to the drought. God, it seemed to Martínez, was mocking the impoverished people of San Antonio. “Divine Providence,” he wrote to the viceroy, “lets them exist in order to witness and participate in the misfortune which His Divine Majesty dispenses with impenetrable judgment.”7

Though he railed at God, Martínez saved most of his anger for the leaders of New Spain. The flood, while devastating, had merely exposed the decay left by what the governor saw as a century of neglect and mismanagement by Spanish authorities. Texas, he recognized, had always been treated by the Spanish crown as a distant, unimportant hinterland, leaving outposts like San Antonio—even before the flood—in desperate straits. When the violence of a revolution shook New Spain during the 1810s, the result had been the rapid erosion of an already weak Spanish presence in Texas. In the years since, authorities in Monterrey and Mexico City had been either unable or unwilling to bolster Spain’s position in the region, which struck Martínez as an almost willful abdication of their responsibilities. In nearly every letter he wrote as governor, Martínez complained that lack of support from his superiors had effectively abandoned Tejanos—as Spaniards in Texas called themselves—along New Spain’s northeastern frontier to their enemies. His tirades about the “impenetrable judgment” of Providence, then, poorly masked Martínez’s underlying conviction that the misery of Spaniards in Texas was tied directly to the poor judgment of authorities in New Spain.8

What Martínez did not know, however, was that powerful forces had been destabilizing the Texas borderlands in ways that Mexico City could not control. Far beyond the confines of New Spain, a revolution in cotton had begun in Europe during the early 1800s when the burgeoning British textile industry developed an insatiable hunger for cotton as a cheaper, more comfortable, more durable alternative to wool. The crop became, almost overnight, one of the most valuable commodities in the Atlantic world, unleashing an economic storm that soon swept across the Atlantic Ocean and began reshaping the North American continent. One of the largest migrations in United States history ensued, as hundreds of thousands of Americans poured into the Gulf Coast region that would become the Cotton South of the United States—places like Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana—where alluvial soils and a long growing season promised ideal conditions for cultivating this newly profitable crop. By 1819, as Martínez despaired for Texas, the revolution in cotton had remade the southwestern United States into one of the primary engines of a new global cotton economy. And because all of this took place along the northeastern edge of New Spain, powerful forces unleashed by cotton began making their way across the landscape of Spain’s tenuous holdings in Texas.

Although Martínez could not know it, the desolate condition of Spanish settlements in Texas owed as much to the rise of this new global cotton economy as it did the failings of Mexico City. Alongside the Americans who flooded into places near the Spanish border had come an equally powerful new trading market geared toward supplying them. Indian nations in Texas, as a result, had vastly escalated the frequency and violence of their raids against Spanish villages in order to feed this voracious new market with horses and mules. American traders hoping to profit from those tribes, in turn, established illegal trading posts in eastern Texas, while smugglers used the Texas coast to funnel enslaved Africans into the flourishing new slave markets of the Mississippi River Valley. The result was a dramatic reorientation of economic and military power along the U.S.-Texas border that forced impoverished communities like San Antonio to expend their few resources on repelling invaders and began to collapse Spain’s presence in the region. Indeed, by the late 1810s Indian raids and armed incursions by foreigners had become so unceasing that Martínez feared he might have to abandon the province entirely. While it brought prosperity to the southern United States, the revolution in cotton brought chaos and turmoil to northern New Spain.

Governor Martínez had seen firsthand how the neglect of Mexico City and the forces unleashed by cotton had combined to overwhelm Spain’s presence in the Texas borderlands, even if he did not fully understand their origins. And in the aftermath of the 1819 flood, Martínez would turn to the very source of his troubles as an unlikely means of salvation, making the remarkable decision in 1820 to invite the cotton revolution into the Texas borderlands in order to save the region for New Spain.

Indian Country

As the people of San Antonio attempted to rebuild, Governor Martínez struggled to understand how Spain’s presence in Texas had edged so close toward ruin. The Spanish, he knew, had claimed control of the region since the sixteenth century, although that had long been more an assertion than anything else. When conquistadors found neither gold nor silver in Texas during the 1540s, Spanish authorities chose to ignore the region throughout most of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Only when French explorations of the Texas coast during the late 1600s threatened their claims did Spanish officials push to establish a permanent presence in the region. Numerous Spanish forts and missions were erected throughout the province during the years that followed, nearly all of which ended in failure. Reading through the reports of his predecessors in San Antonio’s government archives, Martínez could easily understand why. Letters from officials in Texas during those years invariably complained of inadequate support from Mexico City: too few troops assigned to defend such a vast and unsettled frontier; heavy-handed trade restrictions enforced by the crown that retarded the region’s economic growth; the lack of a shipping port, combined with undeveloped roads, that left the region dangerously isolated from the rest of New Spain. Few settlers, as a result, proved willing to abandon New Spain’s interior for the insecurities of this far-flung frontier, leaving the Spanish population in Texas perpetually anemic.9

By the onset of the nineteenth century, the permanent Spanish presence in Texas had not grown beyond a handful of small villages. San Antonio, the capital, was the largest and most developed in the province, boasting around twenty-five hundred people divided between civilians and the royal troops who guarded the town and nearby decaying missions. A hundred miles downstream stood La Bahía del Espíritu Santo, a small settlement of about seven hundred scattered around a dilapidated presidio and two missions.10 Originally located on the site of an abandoned French settlement, La Bahía had been moved in 1749 to its permanent location along the southern San Antonio River, near the Gulf of Mexico.11 Villagers in both outposts depended on ranching for their survival—running horses, cattle, and goats on ranches fronting the river—although that provided only a meager existence.12 Three hundred miles farther east, along the Louisiana border, stood the hamlet of Nacogdoches. Founded in the late 1770s, in the wake of the collapse of nearby missions, Nacogdoches had managed by the early 1800s to grow into a hardscrabble community of around eight hundred. Isolated by hundreds of miles from any other settlement, Spaniards in Nacogdoches survived on ranching and an illegal trade in contraband goods—including a small trade in slaves—that locals maintained with Louisiana.13 Life along the farthest edge of New Spain was precarious, and Spaniards in Nacogdoches struggled. “There,” the governor of Texas noted in 1803, “the inhabitants subsist w...