eBook - ePub

The Great Dismal

A Carolinian's Swamp Memoir

Bland Simpson

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Great Dismal

A Carolinian's Swamp Memoir

Bland Simpson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

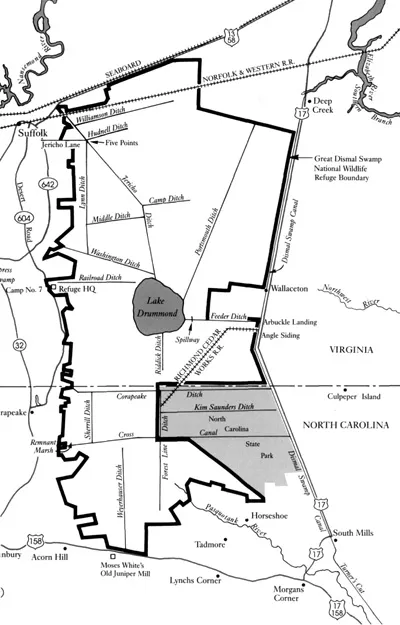

Just below the Tidewater area of Virginia, straddling the North Carolina-Virginia line, lies the Great Dismal Swamp, one of America's most mysterious wilderness areas. The swamp has long drawn adventurers, runaways, and romantics, and while many have tried to conquer it, none has succeeded. In this engaging memoir, Bland Simpson, who grew up near the swamp in North Carolina, blends personal experience, travel narrative, oral history, and natural history to create an intriguing portrait of the Great Dismal Swamp and its people. For this edition, he has added an epilogue discussing developments in the region since 1990.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Great Dismal an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Great Dismal by Bland Simpson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: Drummond’s Pond

“One thinks if God ever made a fairer sheet of water, it is yet hidden away from the eyes of mortals.”

—Alexander Hunter, A Huntsman in the South, 1908

When I was a boy, my father and I used to go out boating on the broad, black Pasquotank River, running through Elizabeth City, North Carolina. We had a 1 1/4 horsepower motor that stayed clamped to a sawhorse in our garage until the Saturday or Sunday afternoons when he would haul it forth and put it in the trunk of our maroon humpback ’52 Dodge and we would drive to a boathouse on the Camden causeway across the Pasquotank, rent a gray wooden skiff, and set out from there.

Ours was a riverine world, and the dark water was everywhere. Already on our ride to the causeway we would have crossed Gaither’s Lagoon, where my first boating had been in an unseaworthy forty-gallon washbucket, then gone for a mile along Riverside Drive on the western shore, past houses on stilts out over the water and past the millionaire oilman’s yacht and the machineshops and marine railways and the yacht club that put on the hydroplane races each fall, then up and over dark Charles Creek and right at Dog Corner, along Water Street past the fishhouse and onto the big drawbridge itself.

Here a ferry once led to the Floating Road to Camden, before the bridge and causeway, but I didn’t know that then. I had no notion that anything had ever been different than it was now, or ever would be. In our little gray skiff my father would guide us unhurriedly past the short cypress trees in the shallows. He had been a pilot and a navigator in the Navy during World War II, and when we were well out he would give me the motor handle, pick a heading, and in a bemused nautical fashion say something like, “Steer her for that stob yonder, sailor!”

Legions of turtles basked on logs and timbers at the river’s edge, and we saw water moccasins and muskrats gliding in the shadows of treelimbs hanging way out from shore. Always we went upstream—for the river became too broad a bay below town for us to venture south—around the horseshoe curve where the Pasquotank narrowed, past the burned-out shell of the Dare Lumber Company and the rotting pilings of the long-gone oyster-shucking houses, then under the tawny drawbridge, where the momentary dark and the echoed drone of the little engine as we passed beneath always thrilled me.

Alongside old wharves where steamboats once called we would cruise lazily for a bit, never going any farther upriver than a point even with a great grain elevator, about a mile from where we had begun. I could see how the river was narrowing still, and I wondered: where did it go from here? If someday we kept on, instead of turning downstream for the boathouse and home, where would it take us?

If we followed it all the way, my father used to tell me, we would disappear with the river into the Great Dismal Swamp.

We would not have been the first.

The Great Dismal has been around for ten thousand years, five hundred generations, and some unknown Indian man, woman, or child who sleeps deep beneath the mantle of peat, the floor of this great boggy wood, unremarked and unmourned holds that honor. The Powhatan had hunted the Swamp in that ancient age when it was a great reach of open marsh. Their bola-weights, spheres and ovoids and dimpled stones once thonged together and slung at waterfowl, have turned up all over the vast morass, most along the Suffolk Scarp, the ancient Pleistocene seabeach at the Swamp’s western edge. So have their projectile points, the tools and weapons they went to once the broad marsh had grown up in boreal forest, jack pines and spruce.

The Ice Age had ended and the climate warmed, and the cold-weather woods fell in succession to new forests, first of beech and birch, then of oak and hickory, and these went down in turn to a wet stretch of cypress and gum and a cedar here called juniper. Still the Powhatan were in the Great Dismal, and not just to hunt. They left behind them potsherds and pollen, the spore of maize, grains too heavy to be wind-borne far from where they grew—the Indians were farming at the very heart of the Swamp.

Nansemond was the name of one of thirty peoples that Wahunsonacock—Chief Powhatan, father of Pocahontas—counted among his empire in the early 1600s. Their home then was in the Swamp along the Suffolk Scarp, but three centuries after Jamestown a few of them clustered together around the village of Chuckatuck, north of Suffolk, Virginia, in the 1930s, there to die out as timber outfits great and small cut the last of the Swamp’s virgin forest. None now speak that tongue, but in my lifetime a Nansemond named Earl Bass hunted the Swamp from the north side.

From car windows as a boy I stared at Earl Bass’s Swamp, the corridor of switch cane and big pines between Suffolk and Norfolk that is U.S. 13/58. And I saw the cypress go to gold and rust each autumn in the sloughs along U.S. 158, between Morgans Corner and Sunbury. My Ferebee cousins in Camden carried me into the Swamp’s southern edge, for it was their own backyard, and we its diminutive natives. I was no Nansemond, but I knew I was Powhatan aplenty from the moment my great-aunt Jennie told me I was kin to Pocahontas—that through the Virginia Blands a smidgen of her blood ran in my veins.

Mostly I knew the Swamp from countless rides up and down the Canalbank, the twenty-two-mile straightaway of U.S. 17, through pines and reeds and fields from South Mills, North Carolina, to Deep Creek, Virginia. The dark Dismal Swamp Canal this road ran beside was the watercourse that tied the Chesapeake to the Albemarle, and for all my growing up I watched the implacable jungle beyond it and heard its simple standard lore: the Swamp was full of runaway slaves and escaped convicts that the law wouldn’t follow in. And I was too young at first to understand or have a sense of time before and beyond my own, believing that these slaves and outlaws were there right then, lurking and staring out at me and my family with bad designs from behind the green curtain as the Africans on the riverbank had stared at freshwater sailor Charlie Marlow in Joseph Conrad’s tale, “Heart of Darkness.”

North beyond all this Swamp was Norfolk, the sprawled-out Navytown queen of Tidewater Virginia, provincial capital for northeastern North Carolina as well. So long allied and tied to each other were Norfolk and our northeast that one Hampton Roads editor, frustrated by decades of conflict with Richmond, hoped in the Herald in 1852 that his “people release themselves from bondage by annexing the city, come what may, to North Carolina—who would at least treat us with decent and common justice.” We small-town Carolinians loved the whole waterfront shebang that the radio called the “world’s greatest harbor,” and we loved the big wilderness that lay between us and the city.

On many of the days of my youth, going up to Norfolk to see my Lamborn cousins, up to Norfolk to shop for suits and shoes, my mother behind the wheel of our pale blue Plymouth station wagon, up to Norfolk on the school bus on field trips to the zoo, I, like Conrad’s Marlow, had gazed back at that bright darkness and thought his same thought:

When I grow up, I will go there.

Nearly twenty years passed before I got the chance.

One Indian summer in the early 1970s, New Hampshireman John Foley and I went down east out of the Carolina Piedmont, through the last slow rolling hills near Rocky Mount, into the flat uncrowded farm country of the Coastal Plain. In Elizabeth City we intended to rent a canoe or a small skiff, and we failed. The town I remembered was gone—the thriving riverport, the boatbuilding town was no more. No one had small craft to let.

We went into the lobby of the New Southern Hotel, a bloodred brick building at the corner of Road Street and East Main, and started calling around the countryside for outfitters, finally finding one in Virginia Beach. By late afternoon, when we got back to the gateway into the Swamp with our gear, the day had grayed up. We parked our station wagon at the far end of the Lady of the Lake tourboat parking lot at Arbuckle Landing, where the wide Feeder Ditch comes down out of the heart of the Swamp and meets the main north and south Canal.

With the same blind homage to the Irish poet that thousands of pilgrims have shown, since his 1803 ballad “The Lake of the Dismal Swamp,” we christened our craft the Tom Moore and pushed off from the small dock. The Sportsman’s Inn, a grill back at the Landing, fell away behind us, and the cries of howling dogs east of the Canalbank faded.

“Looks inviting,” Foley said as we passed a ladder overgrown with vines going from water’s edge to the top of the high bank, the sides of the deep cut through an ancient oyster reef flecked with white.

We paddled westerly up the shallow canyon at a sprint, because it had been drizzling since we put in and also just to hold our own against the strong current. At dusky dark in a heavy rain we reached the spillway outpost, Waste Weir. On the wooded peninsula on the south side of the Feeder we pitched our tent, got a wet-wood fire going, cooked T-bone steaks and drank Rittenhouse rye, and talked into the night about just where on the face of God’s extremely green earth we had gotten ourselves to. Swamp rats, we fancied ourselves.

It was a stormy Monday, and I relished every moment of it. The rain had not let up for more than twenty minutes since we arrived at Waste Weir. Again and again lightning lit up the outpost with blasts of calcium-white light: the small screened and roofed mess hall where we sat, the docks and piers and covered boathouse here on the spit, the spillkeeper’s house and garden beyond the spillway.

Each large crack of thunder rolled over the Swamp like a great log rolling over a vast tin ceiling. When we were in the thick of a piece of storm and the lightning was very close, the thunder boomed out with even intensity all around us and receded slowly, echoing all the way, for ten seconds or more after each crash, a slow and marvelous roar.

Feeder Ditch at Lake Drummond, outlet locks, about 1890

A little past eleven that first night there was a fairing off, and we left the mess hall to walk around the spill. Frogs were moving, the clouds broke open, and the waxing Harvest Moon shone through. Standing on the spillway itself and looking back down the Feeder was astounding: the ditch was barely visible by moonlight, but when the lightning flashed in the near distance the waterway lit up for a second at a time, a silver strand that seemed to lead straight into a jungled nowhere.

Next morning, the spillwayman hailed us from the house across the ditch, and Foley and I went over and had coffee with him. Almost as soon as he had opened his mouth, speaking in Outer Banks soundside, I asked him,

“Where in Dare County you from?”

“Hatt’ras Oyland,” he said, “but Oy been all over Virginia with the Corps of Engineers.” His name was Nat Midgette, and he was three shy of thirty years with the Corps. He wore large thick glasses and had both lenses on retirement.

“You be careful bout your fires over there on that point,” he said. “We had to pump water down a hole over there, peat fire got started by some coals that was still live. Took two days and we still like not to got it.”

This was no small warning. Fires have long deviled the Great Dismal. In 1806 a great fire burned over the Swamp for more than a month. Shinglegetters threw tens of thousands of cypress and juniper shingles into a canal to save them, but the uppermost were above water and they burned away—drenched shingles below them rose to the surface, dried in the heat, and burned as well. An 1839 blaze scorched miles of Swamp in the northwest, and a hunter boating through the same section sixty years later after another big burn there gazed out over thousands of smoldering, smoking acres and called it a charred desert.

So the record went, and worsened: the 1923 fire that burned for three years over a hundred and fifty square miles; the latesummer fires of 1930 that burned over a thousand acres each and the October fire that fall that burned ten thousand acres before November rains put it out; fires burning at will in the Swamp all through the Great Depression after all parties, all agencies gave up; the deep peat fires of 1941 and 1942 that clouded the coastline so badly that Hampton Roads was endangered—little traffic of any sort could move, including the U-boat patrols offshore—and it took the Army and the Navy and the governors of Carolina and Virginia to make the war effort put out the fire in the Swamp.

But Nat Midgette didn’t have to read the whole record to Foley and me that first morning over coffee, for all that too was Great Dismal lore I’d long heard, of firefighters disappearing into flaming pits where the peat had burned out from beneath them and they had fallen through the top crust, of pinetops exploding like fireworks and cascading high over plowed firelanes to ignite the heated, waiting woods beyond. We would be careful about our fires over there on the point.

The soundsider watched as we unhitched our canoe and paddled around the point, up through the profusion of yellow cowlilies all abloom around the banks. At the head of the lagoon was a boat railway, once driven by hand winch and now by motor, for moving small craft from the Feeder Ditch level below the spillway to the Lake level above.

We dragged the canoe up the railway to the higher water, and, as we started on in, Nat Midgette called after us:

“It says be back by six, but you all come on back from the Lake whenever you want to.”

The sun was burning off a heavy mist from the storm and the night, and the air was cotton thick, dishrag damp. Foley in the bow spotted catbirds and bluejays, and a loon led us on up the ditch, whose banks were now even with the water. Ahead of us in heavy-laden grapevines and in wild hedges of brilliant orange jewelweed the loon would alight, awaiting us and then mo...