![]()

1 Origins

Nineteenth-century observers spoke of cities’ “magnetic attraction,” which drew multitudes from the hinterlands. A closer look, however, shows that many aspects of this cityward movement were, and remain, unknown. Reality was, as usual, rather more complex and less straightforward than myth. Clergymen who inveighed against evil Boston’s corrupting rural youth did not know that about half of the men moving to Boston from its environs were already “family men,” hence presumably less susceptible to the Sirens’ call of debauchery.1 But that is getting ahead of our story.

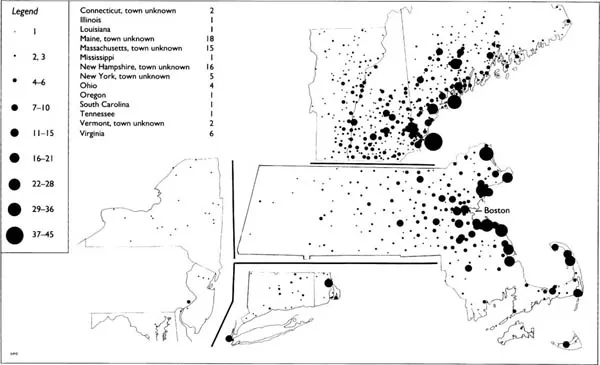

During about the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, Boston drew its migrants (all references to “migrants” are to native-born unless otherwise specified) from an area extending from the coast of Maine across New Hampshire and Vermont, then contracting to the south to include Massachusetts east of the Connecticut River, a sliver of northern Rhode Island, and the peninsula of Cape Cod (see Map 1.1). The city’s attraction seems to have been augmented by ease of travel and reduced by the competing attraction of other urban areas. Few Massachusetts men came to Boston from west of the Connecticut River, for New York City dominated that area.2 Of the 2,808 men in this study, Massachusetts provided about 40 percent of the 2,165 who were in-migrants to Boston (there were 643 Boston natives), followed by Maine (about 25 percent) and New Hampshire (about 22 percent). Allow Vermont a mere 7 percent and but 6 percent remains for “others.” These proportions held, with minor variations, at least from the 1820s through the Civil War.

Changing Sources of Migrants

Early in the century, before the development of New England’s extensive railroad network, migrants to Boston tended to hail from areas from which the journey to the city was easier: the coastline and along well-traveled interior routes (rivers and, later, turnpikes and canals). With the spread of rails throughout New England after the mid-1840s, more men from the interior towns began to arrive, changing the mix of skills they brought to the labor market away from maritime and toward agricultural. Of course, after about the 1830s they could not farm in Boston so they had to take on new occupations there.

MAP1.1

Birthplaces of All In-Migrant Sample Members

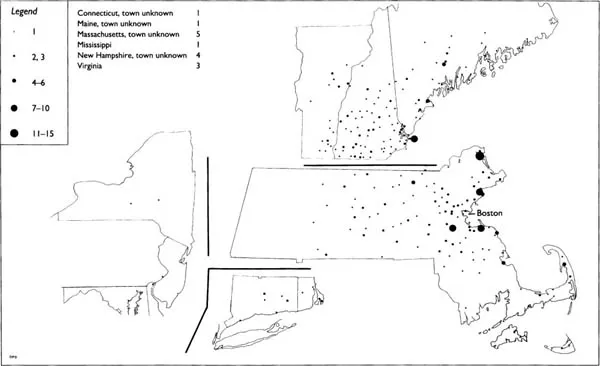

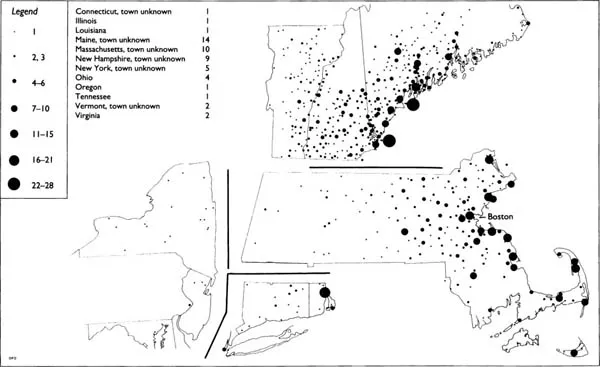

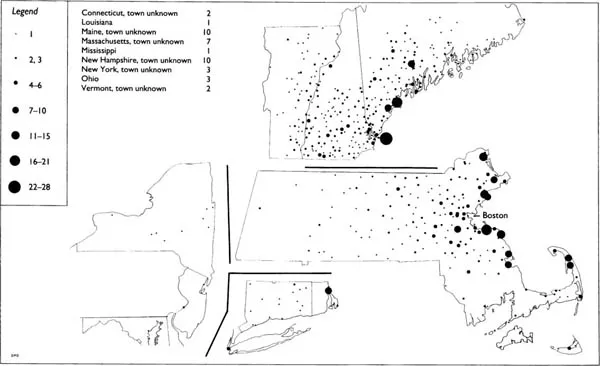

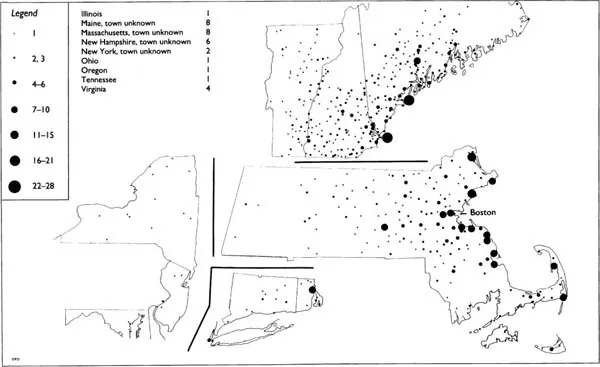

The spatial distributions of these earlier and recent in-migrants, separated into those who entered Boston before 1841 and those who arrived after 1845, are presented in Maps 1.2 and 1.3. Before 1841 New England’s railroads were concentrated near Boston and presumably transported few in-migrants from distant places, whereas after 1845 the system began penetrating to all parts of the region. Comparing the maps one may note the striking opening up of interior regions as sources of migrants.

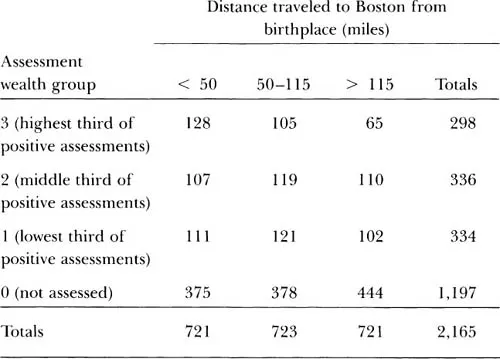

Most of the men who moved to Boston came from communities within 100 miles of the Hub: about a third moved less than 50 miles from their birthplaces to Boston, another third between 50 and 115 miles, and the remaining third over 115 miles. Since New York City was 240 miles distant, this suggests the relatively compact area from which most in-migrants came. As one might anticipate (see Table 1.1), those who moved the longest distances to Boston were probably the least well off and thus were destined not to do as well as those who had some family nearby (fuller details on the concept of “assessment wealth group” appear in the next chapter).

The maps of sample members’ birthplaces, separated by sample (Maps 1.4 and 1.5), can only suggest what statistical inquiry reveals: the group of native-born men residing in Boston as of 1870 had come from a larger number of different communities than had their predecessors of 1860, and these communities tended to be farther away; the average distance to Boston from in-migrants’ birthplaces rose from 97 to 104 miles during the Civil War decade. The increase, though small, was statistically significant. (Although married sample members tended consistently to come from slightly farther away from Boston than did the bachelors, this difference was not statistically significant.)

Most migrants to Boston came from small towns; apart from the few major cities in the region, small towns were the norm.3 These men came from farms, even though their fathers might not have called themselves farmers, because farms constituted the settlement pattern in those towns. Almost every rural family grew something, kept some animals, resided by itself in a structure separate from the residences of other households (in nineteenth-century census listings of New England’s towns, the virtual one-to-one correspondence of houses and households is notable).4 The migrants, then, typically grew up in towns of less than a thousand population; the families in such towns were dispersed over the countryside in farms which, by 1850, averaged about 125 acres each and of which, again on average, about a third was cultivated, with the rest in pasture and woodlots.5

MAP1.2

Birthplaces of In-Migrants to Boston before 1841

MAP1.3

Birthplaces of In-Migrants to Boston after 1845

Table 1.1

Assessment Wealth Group Compared with Distance Traveled to Boston, Both Samples Combined

Source: All tables in this chapter are based on sample data. Chi-square significance > 0.0001. Regression equations relating assessed wealth to distance from birthplace to Boston were not statistically significant.

In Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, the 1850 census enumerated just over half the adult males as farmers. In Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, where the trend toward urbanization was much more pronounced, only about a third were farmers.6 Among the men in the study, the proportion of migrants coming from outside Massachusetts whose fathers were described as farmers was 49 percent; for those from within Massachusetts the fraction fell to 26 percent. Neither value departs markedly from the census norm so it appears that migrants’ fathers were farmers to about the extent usual around 1850 in New England.

MAP1.4

Birthplaces of In-Migrants to Boston, 1860 Sample Members

MAP1.5

Birthplaces of In-Migrants to Boston, 1870 Sample Members

Fortunately for historians, Lee Soltow has chosen three rather large nationwide samples of free adult males in the U.S. population as of 1850 (size 10,393), 1860 (size 13,696), and 1870 (size 9,823). He did this by obtaining National Archives population census microfilms, inserting them in a microfilm reader, and turning the crank handle a predetermined number of times until an eligible male’s entry appeared (hence his designation of “spin samples”).7 In 1850, according to Soltow, the nationwide average value of real estate owned by native-born farmers was about $1,400.8 He does not break down the 1850 wealth figures for native-born farmers by age, but if the trend is similar to that he reports for 1860, the average value of real estate owned by native-born farmers aged over 40 in 1850 would have been about $2,250.9 These figures permit rough comparisons concerning the prosperity of the families from which the migrants came. As is usual in census-based studies, there is considerable attrition: by 1850, at least 631 of the 2,165 migrants’ fathers were already dead, leaving only 1,534 who might have reported wealth in the census. Of them, 406 reported zero wealth to the enumerators, leaving 1,128 who might have possessed wealth; of them, 717 reported some wealth; the other 411 fathers could not be located in the census (likely because some of them were dead). The oldest third of these 717 fathers, aged 62 and over as of 1850, averaged about $3,600 in real estate, while the middle third, aged 51 to 61, averaged $3,100. The youngest third, aged 50 and under, averaged $2,750. Some 77 percent of native-born farmers nationwide who were aged 40 and over reported some wealth to the census enumerators,10 as compared with 717 of the 1,129 sample members’ fathers (64 percent). Adding in the 406 fathers who reported no wealth yields an overall average wealth for the sample members’ fathers of just about $2,000. Taking into account the slightly lower than average wealth reported and the markedly lower than average proportion of fathers who reported any real wealth at all, it would appear that the migrants left from homes somewhat less well off than the average.

Leaving Home

A “typical” migrant to Boston was born in a town of under a thousand population, spent the first 18 years or so of his life in or near that town, and was then ready to strike out on his own.11 This was not a sudden change in status for him because from about age 15 he was likely to have been working “out” for other farmers, usually within a few miles of home, or to have been learning a trade. David W. Galenson’s examination of the biographies of almost 300 “New England manufacturers” memorialized by one J. D. Van Slyck in 1879 suggests that the mean age of leaving home for the 233 men for whom that datum was provided was 18; more than 80 percent of them had left by age 21. Interestingly, about 52 percent of their fathers had some connection with agriculture, as against 49 percent of the men in this study. Galenson suspects that his manufacturers may have departed a bit earlier than was usual for those who would go into nonmanufacturing pursuits. He also found that having a father who was a farmer tended to delay a sons departure.12 The data in this study were more precise but do not speak directly to the same question because a sample member’s age at departure from home was almost never recoverable from the nineteenth-century sources. As Table 1.2 shows, however, one may place an upper limit on the age at departure from home for those sample members who arrived in Boston unmarried by examining their ages at arrival in the city. This distribution would indicate that about half of the single in-migrants to Boston arrived during their early twenties, but since the principal source for determining their arrival in the city was the city directory, which tended not to list men under age 21, it is likely that quite a few of them arrived a year or two before that, in their late teens. Assuming that they had moved directly to Boston with no stops along the way, this accords well with Galenson’s finding of a large clustering of departures from home around age 18.

One may obtain some blurred glimpses of the in-migrants “on the road,” so to speak, since several of them appear twice in the manuscript population census of 1850 or 1860, once with their families “at home,” again with a farm family a few miles away, listed as “laborer.” *Aaron B. Hayden was enumerated 29 August 1850, aged 19, with his family in East Livermore, Maine, and also that day as a “farmer” in nearby Jay.13 (He became a tailor and married Mary H. Orne of Lebanon, Vermont, in Boston in 1853; see Appendix C.) His apparent duality of residence could reflect that work for payment was going on or perhaps it indicates “labor exchange,” a method by which farmers traded work at slack times of the year in return for aid at their bus...