![]()

1

BATTLE LINES

We often think of the poor as inhabiting the margins of our world, but that image misses something important. In North Carolina, the poor might better be imagined as the foundation upon which the state’s modern social and economic order was built. That structure first took shape during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as North Carolinians struggled over the organization of wealth and power in the new commercial economy that arose from the death of slavery. Change came about at a frenzied pace. Between 1880 and 1900, the state and private investors financed the construction of more than five thousand miles of new railroad that snaked through the countryside, linking once isolated communities to regional and national webs of trade. On the outskirts of small towns and cities, merchant entrepreneurs built cotton and tobacco factories that turned farmers’ crops into profitable commodities, primarily cigarettes, thread, and cloth. But alongside a host of opportunities, this new world also produced dislocation and want. For black North Carolinians, the cruelties of tenancy and debt peonage destroyed emancipation dreams of independence on the land; white farmers, too, slid into sharecropping as they moved from subsistence to commercial agriculture; and in textile and tobacco factories, rural folk, seeking refuge from hardships on the land, worked sixty-six-hour weeks for wages that made child labor a necessity of life. In all of this, two fundamental questions begged to be resolved: who would reap the bounty of this age, and by what principles would that abundance be shared?1

Struggle over these questions reached a flash point in the election of 1894, which set white elites united in the Democratic Party against a broad but uneasy alliance among African Americans, middling white farmers, and a nascent class of industrial workers. Black Republicans and white Populists joined forces behind a “fusion” slate of candidates and captured two-thirds of the seats in the state legislature. Two years later, they extended their legislative majority and elected Republican Daniel L. Russell as governor. While similar insurgencies erupted in other southern states, only in North Carolina did a biracial Republican-Populist alliance seize such extensive control of state government.

Fusionists used their newfound political power to enact a program of reforms designed, in the words of a former Democrat, to secure “the liberty of the laboring people, both white and black.” They capped interest rates on personal debt, increased expenditures for public education, shifted the weight of taxation from individuals to corporations and railroads, and made generous appropriations to state charitable and correctional institutions. To expand political participation among the 36 percent of the population who could neither read nor write, Fusionist lawmakers required that party symbols be printed on all ballots. And most important, they gave ordinary North Carolinians a voice in local affairs by replacing a system of county government based on legislative appointments with elected boards of county commissioners and city aldermen. The Fusionists’ goal was nothing short of a “revolution in [state] politics.”2

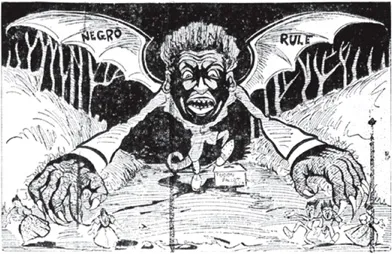

Democrats were stunned by the Fusion victories. Their party had held and exercised power primarily through local networks of kinship and patronage. They were therefore initially ill prepared to counter the Fusionists’ appeal to shared economic interests and issues of equality that undercut those networks and had the capacity to mobilize voters across even the deep divide of race. By 1898, however, Democrats had begun to organize themselves around a new strategy centered on what political economist Kent Redding has described as a “fully politicized white identity.” In past campaigns, Democrats had addressed race as one among many issues, and when they dismissed black voters, they most often did so by arguing that poverty and ignorance made former slaves the dupes of scheming carpetbaggers and scalawags. The appeal in 1898 was different. Under the leadership of young party chairman Furnifold M. Simmons and Raleigh newspaperman Josephus Daniels, Democrats made race their primary issue, and they spoke of blacks as fundamentally “other,” sharing with whites no commonality of interest or intention. The result was a white supremacy campaign of unprecedented focus and ferocity.3

Playing on the racial mistrust that was slavery’s lasting residue, Democrats sought to pry apart a biracial alliance that, at its best, was tenuous, contested, and fragile. They dodged the economic and class issues that held together the Fusion coalition and emphasized instead the specter of “negro domination.” At the heart of their appeal were warnings of miscegenation and sexual danger. Democrats insisted that having secured the ballot, black men would soon claim another prerogative of white manhood: access to white women. In an effort to whip up race hatred, party newspapers created a black-on-white rape scare and accused white Fusionists of sacrificing their wives and daughters on the altar of biracial politics.4

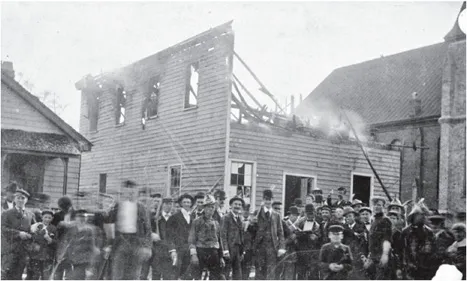

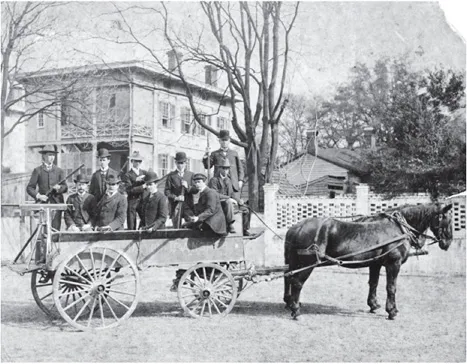

This sharpened rhetoric of race was a potent weapon, but Democrats understood that words alone would not restore them to power. In the closing days of the 1898 campaign, party leaders turned to violence and intimidation. They organized White Government Unions throughout the state and encouraged the party faithful to strip down to their red undershirts, a symbol of the Confederacy’s sacrifice and the late-nineteenth-century equivalent of the hooded robes worn by the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction. The Democrats’ determination to defeat their challengers at any cost was revealed most starkly in the coastal city of Wilmington, where white paramilitaries under the command of former congressman Alfred Moore Waddell staged the only municipal coup d’état in the nation’s history. They marauded through the town’s black district, set ablaze the print shop of the local black newspaper, murdered as many as thirty black citizens, and drove from office a biracial board of aldermen.5

Democrats won the 1898 election by a narrow margin. They claimed only 52.8 percent of the vote, but that was enough to oust most Fusionists from the legislature. The victors moved immediately to silence black and white dissenters. In the 1899 legislative session, Democrats drafted an amendment to the state constitution that aimed to end biracial politics once and for all by stripping from black men the most fundamental privilege of citizenship: the right to vote. The Fift eenth Amendment to the federal Constitution, adopted at the height of Reconstruction, forbade the states from denying the ballot to citizens on the basis of race. North Carolina Democrats, like their counterparts elsewhere in the South, got around that prohibition by adopting a literacy test. In order to vote, citizens first had to demonstrate to local election officials that they could read and write, upon command, any section of the Constitution. That gave Democratic registrars wide latitude to exclude blacks and large numbers of poor whites from the polls. The literacy test was thus designed to achieve the very thing the federal Fift eenth Amendment expressly outlawed.6

In 1900, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Charles Brantley Aycock put the disfranchisement amendment before voters for approval. On the stump, he promised the white electorate a new “era of good feelings” in exchange for racial loyalty. The hour’s need, Aycock declared, was “to form a genuine

white man’s party. Then we shall have peace everywhere. . . . Life and property and liberty from the mountains to the sea shall rest secure in the guardianship of the law. But to do this, we must disfranchise the negro. . . . To do so is both desirable and necessary—desirable because it sets the white man free to move along faster than he can go when retarded by the slower movement of the negro—necessary because we must have good order and peace while we work out the industrial, commercial, intellectual and moral development of the State.” For those who still harbored doubts about supporting a Democratic candidate and the disfranchisement amendment, the party’s Red Shirts offered their own brand of persuasion. On election eve, Alfred Moore Waddell encouraged a white crowd in Wilmington to “go to the polls tomorrow and if you find the negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls and if he refuses,

kill him, shoot him down in his tracks.” The beleaguered remnants of the Populist and Republican opposition could hardly counter such tactics. With a turnout of nearly 75 percent of qualified voters, Aycock and disfranchisement won by a 59 to 41 percent margin.

7The Democrats’ triumph cleared the way for a system of racial capitalism characterized by one-party government, segregation, and cheap labor. With the removal of black men from politics, North Carolina’s Republican Party became little more than an expression of regional differences among whites that set the western mountains, the party’s surviving stronghold, against the central Piedmont and eastern coastal plain. The political contests that mattered occurred not in general elections but in the Democratic primaries, where party leaders exercised tight influence over the selection of candidates and electoral outcomes. Under such circumstances, many North Carolinians found no reason to cast a ballot. Only 50 percent of the newly constrained pool of eligible voters turned out for the 1904 gubernatorial election, and by 1912 the number declined to less than 30 percent. This system of one-party rule sharply circumscribed debate and dampened enthusiasm for the kinds of social investment that Fusionists had championed at the turn of the century. In the state’s cities and larger towns, white middle-class merchants and professionals taxed themselves willingly in order to provide their children with the benefits of education, but spending for rural areas lagged far behind. At the same time, a great gulf opened up between black and white schooling. In 1880, North Carolina had spent roughly equal sums per capita for black and white children, but by 1915 state allocations favored white students over black by a margin of three to one.8

Having asserted that race, not class, was the fundamental dividing line in North Carolina society, the state’s self-styled redeemers set about normalizing imagined racial hierarchies—making them seem natural and self-evident. Since such notions needed to be established anew with each generation, the work of race making was unending. Over time, the architects of white privilege developed an elaborate system of discriminatory law and custom known commonly as Jim Crow, a name taken from the familiar black-face characters in nineteenth-century minstrel shows. Lawmakers passed North Carolina’s first Jim Crow law in 1899, during the same session in which they crafted the disfranchisement amendment to the state constitution. The law required separate seating for blacks and whites on all trains and steamboats. The aim of that and other such regulations was to mark blacks as a people apart and, in doing so, to make it psychologically difficult for whites to imagine interracial cooperation. Segregation also divided most forms of civic space—courthouses, neighborhoods, and public squares—that might otherwise have been sites for interaction across the color line. In Charlotte, soon to be North Carolina’s largest city and the hub of its new textile economy, neighborhoods in 1870 had been surprisingly undifferentiated. As historian Thomas Hanchett has noted, on any given street “business owners and hired hands, manual laborers and white-collared clerks . . . black people and white people all lived side by side.” By 1910, that heterogeneity had been thoroughly “sorted” along lines of race and class. In communities large and small across the state, this process played out a thousand times over as white supremacy erected a nearly insurmountable wall between the blacks and poor whites who had risen in the late 1890s to challenge Democratic power.9

Jim Crow also worked to relegate the majority of black North Carolinians to the countryside and to create, in effect, a bound agricultural labor force. Jobs in the textile industry, which in the early twentieth century would become North Carolina’s leading employer, were, with few exceptions, reserved for whites only. The industry’s boosters promised that factory jobs would free poor whites from want by teaching them the virtues of thrift and insulating them from economic competition with blacks. But segregated employment was far less of a boon than textile promoters claimed. Jim Crow held black earnings to near-subsistence levels, dragged white wages downward by devaluing labor in general, and advanced industrial employers’ interests by tempering white workers’ efforts at organization with concern for the protection of racial privilege.

In all of these ways, the triumph of white supremacy set the stage for an extended period of economic development and wealth accumulation bound up with enduring poverty. Between 1880 and 1900, investors built an average of six new cotton mills a year in North Carolina. The pace quickened in the opening decades of the twentieth century, so that by the late 1930s the state claimed 341 mills and had displaced Massachusetts as the world center of cotton textile production. At its peak, the cotton goods industry in North Carolina employed more than 110,000 people. The story of tobacco, although different in its particulars, followed a similar trajectory. By the 1920s, two North Carolina firms—R.J. Reynolds in Winston-Salem and American Tobacco in Durham—dominated the industry. Their combined market influence enabled them to set prices along the entire production chain, from the purchase of raw tobacco to the sale of cigarettes.10

Together, tobacco and textiles transformed crossroads towns into cities and built some of the great fortunes of the early twentieth century. In Durham, James B. Duke used his family’s tobacco wealth to endow Duke University and to establish the Southern Power Company (today, Duke Energy), which brought electricity to and quickened development in much of North Carolina’s central Piedmont region. The Reynolds family, connected by banking and business partnerships with the Gray and Hanes families, anchored the wealth of Winston-Salem, which in the 1930s one journalist described as a city of “one hundred millionaires.” Greensboro’s Cone brothers, Caesar and Moses, first entered the textile industry as cotton brokers for southern mills and later built an empire on the production of denim. In nearby Burlington, J. Spencer Love consolidated a handful of family mills into Burlington Industries, which eventually became the world’s leading textile firm, and in Kannapolis, Charles A. Cannon oversaw the state’s largest company town. Located thirty miles southwest of Kannapolis, Charlotte, which claimed its own share of textile firms, fed industrial North Carolina’s hunger for investment capital. Between 1897 and 1927, more than ten new banks opened offices in the city, including a branch of the Federal Reserve. The legacy of that development remains apparent today. Charlotte is home to several of the nation’s largest banks, including Bank of America, and ranks second only to New York as a financial center.11

Despite the scope of this economic development and the wealth it generated, North Carolina remained a poor state. In 1938, deep into the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s National Emergency Council issued its Report on Economic Conditions of the South, which explained how circumstances in North Carolina and elsewhere in the region produced poverty that was “self-generating and self-perpetuating.” The average annual industrial wage in the South was $865, as compared to the $1,219 earned by workers outside the region. Southern factory hands’ wages were so low primarily because the workers competed for jobs with a virtually limitless pool of desperately poor rural folk. On southern farms in general, per capita income was only $314, slightly more than half of the $604 earned by farmers elsewhere in the nation. For tenant families—white and black—who owned no land of their own, that figure plummeted to an average of only $74 per person. Those families, the Report observed, were “living in poverty comparable to that of the poorest peasants in Europe.”

Such deprivation left southern s...