![]()

Chapter One: Modernist Visions and Municipal Displays The Founding and Development of German Ethnographic Museums

The ultimate goal of all ethno-graphic activities and with them the general purpose of ethnographic museums can only be: To contribute to the knowledge and understanding of ourselves.—Oswald Richter, “Über die Idealen und Praktischen Aufgaben der Ethnographischen Museen”

The degree of civilization to which any nation, city or province has attained, is best shown by the character of its Public Museums and the liberality with which they are maintained.—G. Brown Goode, Principles of Museum Administration

When Germany was founded in 1871 it possessed only scattered ethnographic collections, leftovers from princely treasure houses, forgotten items in curiosity cabinets, and the ill-gotten gains of adventurers.1 Yet by the first decade of the twentieth century, a number of Germany’s cities possessed internationally acclaimed ethnographic institutions, and the nation’s capital boasted the world’s largest, and according to contemporaries, grandest ethnographic museum. The rapid growth of these institutions was as unprecedented as it was surprising. Their appearance paralleled the creation and development of the German Empire, and they matured against the riotous backdrop of nineteenth-century colonialism. But the movement to create ethnographic museums was not driven by German nationalism or by a particular colonialist vision. City-building rather than nation- or empire-building provided German scientists with the support they needed to pursue ethnology with vigor.

Because ethnology only began to dawn as a scientific discipline in Europe in the late 1860s, German ethnologists benefited from the wave of civic associations that began forming after the Napoleonic Wars and especially the increasing numbers of natural scientific associations that were founded following the 1848 revolutions.2 Scholars have calculated that by 1870, “one German citizen in two belonged to an association,”3 and between 1840 and 1870, up to eighty new associations were founded devoted to the natural sciences alone.4 This changed Germany’s institutional landscape. Associations in the cities sponsored projects devoted to renewal, such as hygiene, welfare for the working classes, public health care, and they eagerly engaged in fashioning signs of their own cultural progress: art museums, natural history museums, opera houses, botanical and zoological gardens.5 Many of the people involved in these associations, and many who would later champion ethnographic museums, were also inspired by the travel literature that began flooding Europe at this time. They were enchanted by Alexander von Humboldt’s cosmopolitan vision, and many were eager to take up his challenge to pursue total histories of the world.6

German ethnographic museums owed their origins to a small number of aspiring ethnologists who seized on Humboldt’s vision and were convinced that they could improve their knowledge of themselves by exploring mankind’s extensive variations. But in many ways ethnology, and especially ethnographic museums, flourished in Imperial Germany because a range of different cities provided this science with particularly fertile ground for its development. Indeed, during the second half of the nineteenth century, German ethnology was an emerging discipline led by intellectual newcomers in cities caught up in the throes of change. It emerged as a science just as German cities were beginning a phase of uncommon growth, and a striking range of citizens in the largest of these cities embraced ethnologists and their institutions because they believed this new, internationally recognized science provided the city that possessed a significant ethnographic museum with a means for exhibiting its citizens’ worldliness and thus for refashioning themselves.

The Shaping of German Ethnology: Adolf Bastian’s Humboldtian Vision

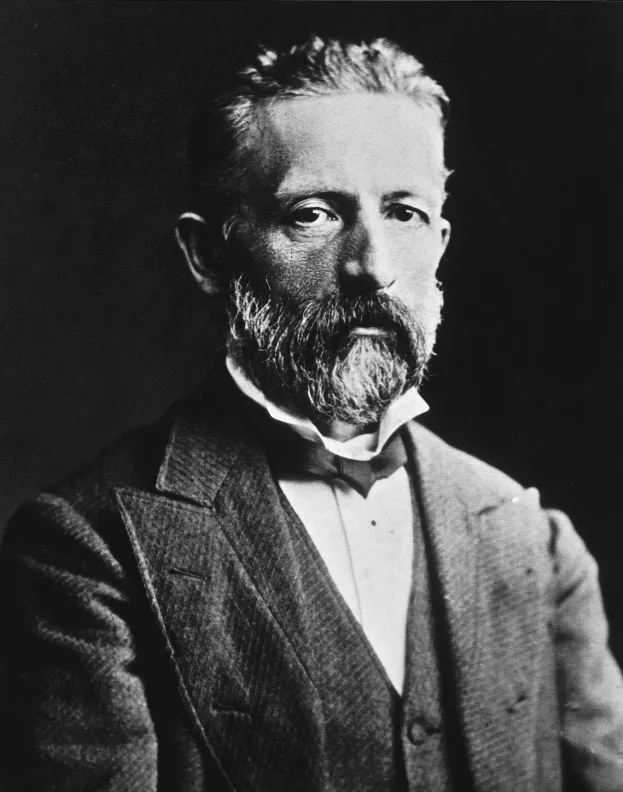

More than anyone else, Adolf Bastian (1826–1905) shaped the development of German ethnology during the second half of the nineteenth century (Fig. 1). He established and directed Germany’s largest ethnographic museum. He founded, contributed to, and edited a number of leading ethnological and geographical journals, and he was repeatedly featured in a number of popular magazines. He was a key player in Germany’s foremost geographical society, the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory, as well as several other scientific associations. He was also the first person in Germany to gain a university position as an ethnologist. By 1895, Bastian had over 230 publications to his credit, and by 1905 his books took up three to four feet of shelf space and included over 10,000 pages.7 There were, of course, a number of other German scholars such as Friedrich Ratzel who also played important roles in the history of this science, and whose viewpoints differed in marked ways from Bastian’s. But it was unquestionably Bastian who set the central trends in German ethnology from the 1860s through the 1880s as he sketched out his vast empirical project, established extensive international networks of collection and exchange, created an ethnographic institution that became the critical point of comparison for all others, and helped to train a number of Germany’s first professional ethnologists and encourage them to harness this new science in pursuit of self-knowledge.8 It was Bastian’s vision that provided the initial framework for German ethnology and shaped the character of Germany’s leading ethnographic museums.

Like many of his generation, Bastian was inspired by Alexander von Humboldt, the leading natural scientist of his age. Humboldt was renowned for his exploration of equatorial America from 1799 to 1804. He produced thirty volumes based on these journeys, which encompassed the botany, plant geography, zoology, physical geography, and political economy of the area. He also contributed to the sciences of anatomy, mineralogy, and chemistry, and he was keenly interested in the relationship between humans and their environment. His masterpiece was the five-volume Cosmos (published from 1845 to 1862), in which he attempted to write a comprehensive description of the universe and a complete account of the physical history of the world. Because of popular demand, the original edition of the first volume alone sold over 22,000 copies, making him one of the most successful authors of his day.9 Humboldt’s writings helped to establish geography as a scientific discipline, and his example influenced both the lifestyle Bastian embraced as well as the character and scope of his ethnographic project.10

Bastian dedicated his first major publication, Der Mensch in der Geschichte, to Humboldt, and in there he set out the essential parameters of the project he pursued for the next forty-five years.11 Bastian argued during a speech he delivered in Humboldt’s honor in 1869, that “world travel” rather than a limited contemplation of texts was the best thing for the “promotion of science.”12 Inspired by Humboldt’s example, he undertook eight major excursions outside of Europe.13 Indeed, he ultimately spent more than twenty-five years of his life abroad—gathering information, collecting for his museum, persuading well-placed individuals in other lands to assist him, and convincing talented young men like Karl von den Steinen to join in his project to unveil the total history of humanity in all its many variations.14

FIGURE 1. Adolf Bastian (1826–1905). The son of a wealthy merchant family in Bremen, Bastian spent over twenty-five years of his life abroad and became the father of German ethnology. (Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

Moreover, much like his intellectual hero, Bastian’s ethnographic project was governed by a set of methodological and political convictions rather than a single overarching theory. His reading of Humboldt’s Cosmos had convinced him that the creation of universal theories about human history were secondary to the accumulation of knowledge about its particulars: “All systems-construction,” he argued during his speech in honor of Humboldt, “remains mere metaphysical illusion unless knowledge of the details has been accumulated.” For this reason Humboldt had posited no great theory, no general explanatory system in his Cosmos; nor, as far as Bastian was concerned, was one necessary. Such “systems,” Bastian argued, “are ephemeral by their nature,” but Humboldt’s method (the development of a vast synthesis based on empirical induction) was “everlasting” and would eventually lead to scientific truths.15 It was Humboldt’s effort to fashion a total empirical and harmonic picture of the world that inspired Bastian’s attempt to unite all knowledge of human history—ethnological, philosophical, psychological, anthropological, and historical—into a huge empirical synthesis and to abstain from issuing tentative explanatory theories.

This methodological commitment to careful, empirical research over “speculative theorizing” prompted Bastian and his counterpart in German physical anthropology, the well-known pathologist Rudolf Virchow, to shun Darwinian schemes of human history and isolate themselves from the race debate.16 Virchow did argue in public debates that Darwinism was dangerous because of its possible association with Social Democracy; but his chief criticism always targeted Darwinism’s speculative nature.17 Bastian took the same position. While he admired Darwin’s travels, he lamented the lack of “factual evidence” that might support his conclusions, and he compared Darwin’s postulates about the “genealogy of mankind” to “fantasies” from the “dreams of mid-day naps.”18 But he found particularly offensive the efforts by Germany’s leading Darwinian, Ernst Haeckel, to popularize these ideas. In his public debates with Haeckel, Bastian denounced these efforts as “unscientific forgery,” lacking a sufficient empirical base for responsible presentation. As he noted, “Nothing is further from my intentions than popularization, because I know that my newly born science of ethnology is still too young for such a daring deed.” While Haeckel strove “above all and with reckless abandon toward popularization,” Bastian believed that only theories based on solid empirical evidence should be used to explain complex phenomena to laymen.19

In lieu of a definitive ethnological theory, Bastian had a set of specific convictions and a three-part plan of action. World history for Bastian was the history of the human mind. He argued, with a strong monogenicist conviction stemming largely from his worldwide travels, that “human nature is uniform all over the globe” and that “if there are laws in the universe, their rules and harmonies should also be in the thought processes of man.”20 Thus Bastian’s first (and highly ambitious) goal was to engage in a vast, comparative analysis of these thought processes during which he expected that his second goal would ultimately take care of itself: empirical laws would eventually emerge. Once these laws were revealed, he believed that they could also be applied to his ultimate end: they could be harnessed by Europeans to help them better understand themselves.

As Bastian wrote in 1877, “the physical unity of the species man [has already] been anthropologically established.” In consequence, his project was focused on locating “the psychic unity of social thought [that] underlies the basic elements of the body social.” The best way to do this, he contended, was not through subjective self-reflection on European cultural history, but by bringing together and examining the physical traces of human thought, the material culture produced by peoples everywhere, which he believed would reveal “a monotonous sub-stratum of identical elementary ideas” with which they could exfoliate the more general history of the human mind.21

Bastian stressed that every group of people shared these “elementary ideas” or Elementargedanken, even though they were never directly observable. Having an “innate propensity to change,”22 they always materialized in the form of unique patterns of thought, or Völkergedanken, reflecting the interaction of peoples with their environments, as well as their contacts with other groups. Elementargedanken were thus hidden behind humanity’s cultural diversity—a diversity that was historically and geographically contingent. Understanding the unique contexts in which each culture took shape, Bastian stressed, was thus critical for gaining insight into the universal character of “the” human being.23 Indeed, it was largely Bastian’s interest in identifying these contexts that led Fritz Graebner to term Bastian the Naturvölkers “Erwecker zu historischem Leben,” quite literally, the one who brought natural peoples (or ostensibly primitive peoples) into history.24

In addition to Bastian’s notion of Elementargedanken and Völkergedanken, it was the idea of geographical provinces that formed the core of his thought.25 For Bastian, the Völkergedanken that characterized different groups of people emerged within identifiable zones where geographical and historical influences shaped specific cultures. Unique Völkergedanken, like “actual organisms,” fit within these particular geographical provinces, shifting and changing as they came into contact with others. This interaction, Bastian emphasized, was the basis of all historical development, and it could be observed most readily in certain geographical areas: on rivers, coast lines, and mountain passes, which he referred to as “Völkertore.”26

Within Bastian’s ethnology, the question of human difference played a critical role. On a basic level, humanity could be divided into two major categories, the Naturvölker (natural peoples) and the Kulturvölker (cultural peoples).27 Having achieved literacy, the latter had a recorded past that historians and philologists could explore. This did not mean, however, that the former were without history or c...