![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Man for Office Is Cole Blease

Like Will Thompson, Joe Childers was a white millworker. A newspaper reporter described him as a “respectable laboring man” with a “good reputation.”1 On the night of March 27, 1912, Childers met Joe Brinson and Frank Whisonant, both African Americans, near the train station in the tiny up-country town of Blacksburg, South Carolina. The meeting proved tragic.

What happened that night among Childers, Brinson, and Whisonant will never be known. Depending on who told the story, Childers either asked Brinson and Whisonant to get him a pint—or a quart—of whiskey or the two African Americans badgered the innocent white man until he finally agreed to buy liquor from them. The three men got drunk. According to Childers, Brinson and Whisonant ordered him to drink all of the whiskey. Fearing for his safety, he drank as much as he could as fast as he could, but he could not drain the bottle. As Childers guzzled the rust-colored rotgut—or maybe it was clear white lightning—Brinson and Whisonant taunted him; when he did not finish, they grew quarrelsome. They forced him into a cemetery and made him take off his clothes. N. W. Hardin, a local attorney, recounted what he heard happened next: “They [Brinson and Whisonant] drew their pistols, cocked them and told Childers to open his mouth, and keep it open, that if he closed it, he would be shot on the spot.” Then, in Hardin's version, Brinson made Childers perform oral sex on Whisonant.2

Following this consensual or coerced sexual act, or what the press dubbed the “unmentionable act”—the phrase commonly used to talk about the rape or alleged rape of a white woman by an African American man—Childers “escaped."He ran straight to the police. The law officers quickly apprehended Brinson and Whisonant and charged them with selling liquor, highway robbery, carrying a concealed weapon, assault with a deadly weapon, and sodomy. The local magistrate fined the two men twenty dollars each. Some thought that the penalty, which was roughly the equivalent of three weeks’ wages for a textile worker, was too lenient. Regardless, Brinson and Whisonant had no money and went to jail.

The next morning E. D. Johnson of Blacksburg got up early and walked to the well in the center of the town square. Johnson discovered that the rope used to pull up the water bucket was missing. Puzzled, he looked around; his eyes eventually stopped at the sturdy stone and brick jail. The front door was knocked down. Johnson peered inside and saw a broken padlock and an open cell. He must have known what had happened. He ran to tell the mayor. It did not take the men long to find the missing rope and the missing prisoners.

“The job,” wrote a reporter, “had been done in a most workman-like manner.” Brinson and Whisonant's cold, stiff bodies dangled from the rafters of the blacksmith shop located just behind the jail. Bound hand and foot, both victims had been gagged, one with cotton, the other with rope. The killers had not wanted them to scream.

Word of the lynching spread through the area, but the crime did not bring together, in the words of a student of southern vigilantism, Arthur Raper, “plantation owners and white tenants, mill owners and textile workers.”3 Instead, the killings stirred discord. “Law and order,” worried the editor of the Gaffney Ledger , “has been flaunted” as “passions [have become] inflamed and reason dethroned.” “Every good citizen,” he was certain, “deplored the crime.” The newsman, however, had no sympathy for the dead. “Those were two bad negroes who were lynched in Blacksburg,” he conceded. “But,” he added, “those who outraged them became worse whites.”4

No one publicly named the “worse whites.”5 Many people, especially in Blacksburg, speculated that a mob—totaling as many as a dozen or as few as six men—drove into town or rode in on horseback from the mill villages of Gaffney, Cherokee Falls, Hickory Grove, And King's Mountain. Others insisted that the killers were from Blacksburg. Though questions about where the murderers resided lingered, there was little doubt about what they did for a living. “My idea,” wrote N. W. Hardin, “is that as Childers was a factory operative, the lynching was done by the operatives of the surrounding mills, trying to take care of their class.” If millworkers committed the crime, townspeople were sure where the larger blame for the murders lay. “Some of the d— fools are already saying,” reported Hardin, “this is Bleasism.” The Gaffney Ledger echoed this view. “If a majority of the people of South Carolina

A lynching in the South Carolina upcountry sometime before World War I. According to John Hammond Moore (“Carnival of Blood: Dueling, Lynching, and Murder in South Carolina, 1880-1920,” unpublished manuscript), this picture probably depicts the lynching of Joe Brinson and Frank Whisonant in Blacksburg, March 1912. (Historical Center of York County, York, South Carolina)

want Blease and Bleasism,” the editor wrote of the lynching, “they will have it in spite of those who desire law and order.”6

Bleasism was the term used to designate the political uprising of first-generation South Carolina millworkers. This electoral surge took its name from its standard-bearer, Coleman Livingston Blease. “Coley,” as his loyal backers called him, had occupied the governor's office for more than a year and was gearing up for his reelection drive when Brinson and Whisonant were killed. Although Blease did not play any role in the murders, commentators who linked him to the disorder in Blacksburg were, at least in part, right. Blease's racially charged, antireform campaigns and his irreverent leadership style inflamed many of the same cultural, economic, and sexual anxieties that ultimately led some working-class white men to lynch African American men.

Despite the homoerotic overtones of the meeting at the railway station, the killers must have decided that Childers was “innocent,” that he had been “raped,” and that the crime symbolized more than one shocking evening in a cemetery. The imagined rape of the millworker Joe Childers may have represented in microcosm the assaults on white manhood posed by industrialization. Even more than the rape of a white woman, the rape of this white man by another man graphically represented male millworkers’ deepest fears of emasculation. That the perpetrators were African Americans magnified the offense. The alleged sexual attack not only erased the color line but also placed an African American man “on top,” in a position of power over a white man. A few male textile workers appear to have made a connection between how the “rape” of Childers feminized him and how industrialization stripped them of control over their own labor and that of their families, and thus their manhood. Some southern white wage-earning men apparently felt that industrialization could potentially place them in the position of a woman: vulnerable and dependent, powerless at home and in public.

By murdering Joe Brinson and Frank Whisonant, the killers tried to reassert their manhood.7 The same fierce determination to uphold white supremacy and patriarchy that led to the Blacksburg lynching propelled Cole Blease's election campaigns. The same sexual and psychological fears that drew the lynch mob to the jail that spring night in 1912 brought many more men to the polls a few months later to vote for Blease. Middle-class South Carolinians—professionals and members of the emerging commercial elite—also connected the lynching in Cherokee County with Blease's political success. They argued that both stemmed from the collapse of “law and order” in the mill villages and together demonstrated the need for reform.8

The anxieties that fueled Bleasism and triggered the Blacksburg lynching were not confined to South Carolina or, for that matter, to the American South. Across the United States and indeed the globe, the reconfiguration of productive landscapes—the shift from fields to factories—jarred gender relations. Industrialization triggered an almost-universal crisis of male identity. In South Carolina, the crisis of masculinity among first-generation millhands aggravated race and gender relations and eventually spilled over into politics, splitting the state along class lines.9

South Carolina's turn-of-the-century mill-building crusade and white supremacy campaigns set the stage for the political emergence of Cole Blease. In 1880 there were a dozen mills in South Carolina. Twenty years later the number of textile factories had jumped to 115; in 1920 there were 184. As the mills multiplied, the labor force changed. At first, the mills employed mostly widowed women and children, but as the industry grew and the region's rural economy stagnated, more and more men took jobs in the factories. As early as 1910, two-thirds of all South Carolina millworkers were men, and, because of the state's political makeup, most were eligible to vote.10

Industrialization also gave new meaning to South Carolina's traditional geographic divide. A natural fall line, stretching from the North Carolina border in Chesterfield County to the Georgia boundary in Aiken County, cuts across the state, slicing it into two sections commonly known as the upcountry and the low country. A narrow band of sandhills in between is usually referred to as the midlands. More than topography separates these sections.11 During the antebellum era, small farms and a smattering of plantations dotted the upcountry's rolling red clay hills, while factories in the fields exploiting African slave labor dominated the marshlands and reedy swamps of the low country.12 These sharply contrasting economic patterns persisted long after the carnage of the Civil War and the drama of Reconstruction. Although the defeat of the Confederacy destroyed the system of slavery, it also accelerated the transformation of the South Carolina upcountry. Because of the area's access to credit and its abundance of fasting-moving streams, mill building—the thrust of New South industrialization—was concentrated above the fall line.

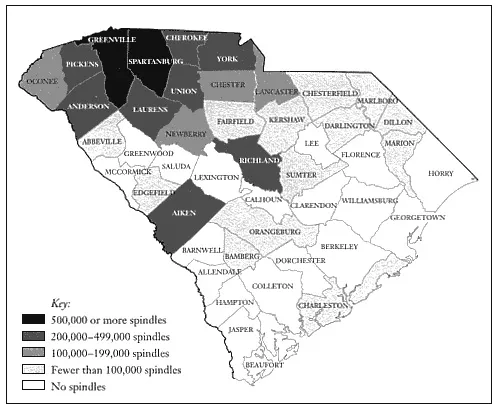

By the time Blease started to campaign for office in 1906, more than 80 percent of South Carolina's textile mills were located in the upcountry, half in Greenville, Spartanburg, and Anderson Counties alone.13 The modernization of the state's economy produced “unbalanced growth.” Growth encouraged more growth, while atrophy bred stagnation. The turn-of-the-century mill-building boom, in other words, benefited the counties of the upcountry, while it skipped over the low country. After this, the state was divided between the relatively modern, industrial, and predominantly white areas of the upcountry and the increasingly stagnant, rural, and overwhelmingly African American sections of the low country.14

Map 2. Textile Spindleage in South Carolina, by County, 1929 (Adapted from Hall et al., Like a Family , xxvi-xxvii)

Meanwhile, unlike what happened in other southern states, South Carolina lawmakers did not cut poor white males, including propertyless upcountry millworkers, out of electoral politics when they put in place the Jim Crow order in the 1890s.15 But that did not make the state democratic, not even for whites. Besides almost ending black suffrage, the state's 1895 constitution established the basic rules of politics in South Carolina for the next fifty years. Disfranchisement ensured whites a virtual monopoly on state power, but the constitution did not guarantee that all white citizens would be represented equally. For one thing, citizenship was not portable. Voters had to remain in the same place, even the same house, for one year in order to cast a ballot. This provision penalized white millhands, in particular, who in the early twentieth century took advantage of a regional labor shortage by constantly moving around looking for the best deal for themselves and their families. Even when male millhands did stay put, the polls often closed before the end of their shifts, making it impossible for them to vote. The apportionment of the general assembly also diluted democracy in South Carolina. Based, in part, on geography rather than population, it provided rural citizens with a disproportionate amount of political power, especially when compared to upcountry millworkers.16

While the South Carolina Constitution imposed limits on Palmetto State democracy, it also gave the Democratic Party—the only party that mattered after Reconstruction—the right to determine who could and could not vote in its all-important primary. After a long debate, state Democrats in the 1890s decided to extend the suffrage to all white men over the age of twenty-one, regardless of wealth or education. The constitutional poll tax, moreover, applied only to the rather meaningless general election. As a result of these rules and the racial composition of the textile workforce, the expanding mill population possessed considerable electoral strength. By 1915 nearly one out of every seven Palmetto State Democrats lived in a mill village.17 Affirming at the same time the ideal of herrenvolk democracy, that is, of white political equality, the state's emerging political culture also provided poor whites with a powerful ideological lever. Despite constitutional checks on democracy, this myth defined citizenship by race and implicitly put forth the idea that all white men were equal. In the years to come, white millworkers repeatedly demanded that elites honor the tenets of herrenvolk democracy by treating them with the respect and dignity that equal citizens deserved.18

Although Blease's mentor, the quasi-populist and racist leader of the state's disfranchising forces, Benjamin R. “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, had little use for industrial laborers—he once referred to them as that “damned factory class”—Cole Blease himself recognized the electoral harvest to be reaped in the textile communities.19 As soon as Blease turned away from a career in law to one in politics, he focused his attention on the mill hills around his hometown of Newberry. He spent afternoons and evenings in front of company stores and at nearby roadhouses, and he joined the clubs, fraternal organizations, and brotherhoods that textile workers belonged to. Sometime early in this century it was said, and no one disputed it, that Blease knew more millhands by name than anyone else in the state.20 He turned this familiarity into votes. In 1890 he was elected to represent Newberry County in the South Carolina General Assembly. Twice, in 1910 and 1912, Blease triumphed in the governor's race. On a number of other occasions he won enough votes to earn a spot in statewide second primaries or runoff elections. In most of these contests, millhands made up the bulk of his support.21

Male textile workers did not just cast their ballots for Blease, they were fiercely devoted to him. When he went up to the mill hills, poking fun at elites, issuing chilling warnings about black rapists, and slamming “Yankee-ridden” unions, overflow crowds greeted him with “tornado[es] of shrieks, yells, and whistles.” Mill people named their children after Blease, hung his picture over their mantels, and wrote songs and poems about him. “If you want a good chicken,” an upcountry bard was heard to say, “fry him in grease. If you want a good governor get Cole Blease.” When a reporter asked a textile worker why he supported Blease, the man snapped, “I know I ain't goin’ to vote for no aristocrat.” Another millhand once hollered, “Coley, I'd vote fer you even if you was to steal my mule tonight.”22

Millworkers’ allegiance to Cole Blease has long baffled historians. Because he promoted white supremacy, derided national unions, rejected child labor restrictions, and lambasted compulsory school legislation, scholars have accused him of being “a feather-legged demagogue” with “no program for the benefit of the factory workers.” Historians have contended that the reform policies Blease opposed would have saved workers from the misery and poverty of the mill village, but they did not care. They preferred a politician who spouted off about race to one who promoted reform. How, historians have wondered, could such perplexing behavior be explained? Ignorance and false consciousness were the answers most often given. Spellbound by Coley's saber-rattling rhetoric, this argument...