eBook - ePub

A Tale of the Unknown Unknowns

A Mesolithic Pit Alignment and a Neolithic Timber Hall at Warren Field, Crathes, Aberdeenshire

Hilary K. Murray, J. C. Murray, Caroline Fraser, J. C. Murray, Caroline Fraser

This is a test

Share book

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Tale of the Unknown Unknowns

A Mesolithic Pit Alignment and a Neolithic Timber Hall at Warren Field, Crathes, Aberdeenshire

Hilary K. Murray, J. C. Murray, Caroline Fraser, J. C. Murray, Caroline Fraser

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The site of Warren Field in Scotland revealed two unusual and enigmatic features; an alignment of pits and a large, rectangular feature interpreted as a timber building. Excavations confirmed that the timber structure was an early Neolithic building and that the pits had been in use from the Mesolithic. This report details the excavations and reveals that the hall was associated with the storage and or consumption of cereals, including bread wheat, and pollen evidence suggests that the hall may have been part of a larger area of activity involving cereal cultivation and processing. The pits are fully documented and environmental evidence sheds light on the surrounding landscape.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is A Tale of the Unknown Unknowns an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access A Tale of the Unknown Unknowns by Hilary K. Murray, J. C. Murray, Caroline Fraser, J. C. Murray, Caroline Fraser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Warren Field Project: place and context

1.1 Background to the excavation

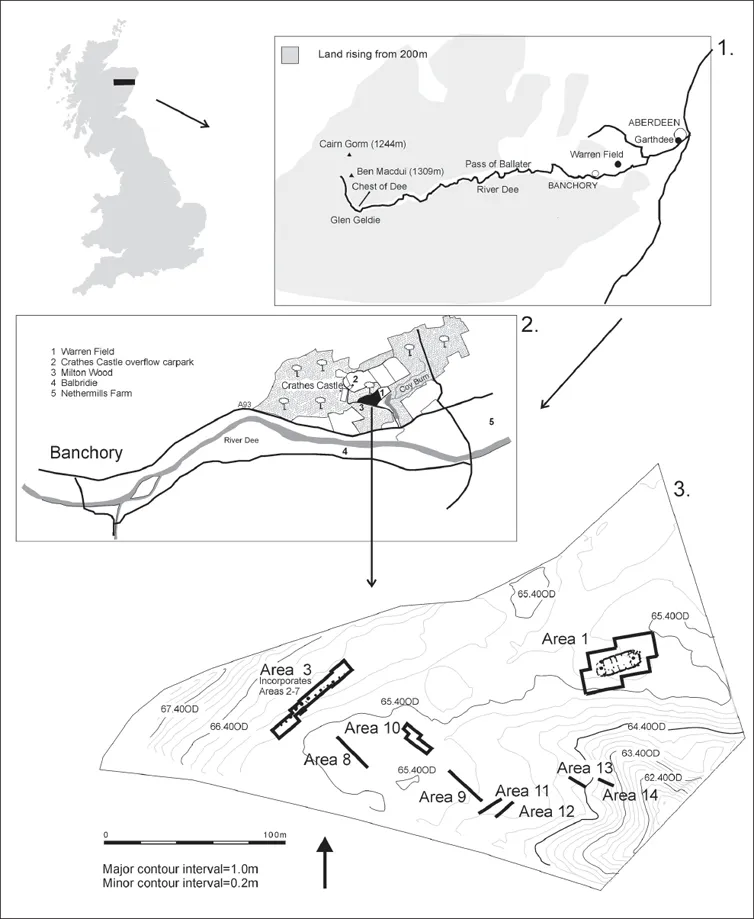

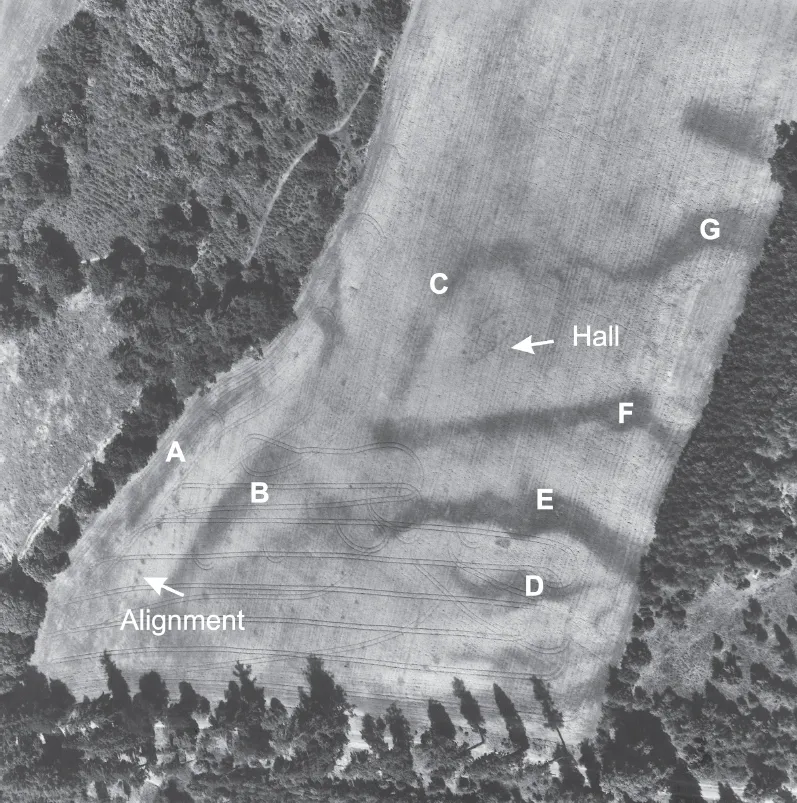

Warren Field, Crathes, Aberdeenshire lies within the estate of Crathes Castle, now in the ownership of the National Trust for Scotland (NTS) (Fig. 1). It is c.600m north of the River Dee and less than a kilometre from an early Neolithic timber hall excavated at Balbridie, on the south bank of the river (Ralston 1982; Fairweather and Ralston 1993). A complex of cropmarks was first identified on aerial photographs taken in the very dry summer of 1976 by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (Fig. 2). These revealed two main features: an alignment of pits (NGR: NO 737 966; NMRS NO79NW18), and a large, rectangular feature interpreted as a timber building (NGR: NO 739 967; NMRS NO79NW17). A large number of far smaller, dispersed features were also visible in the area between the building and the alignment.

The building was protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument in 1978 and the whole field, which had been in arable cultivation prior to 1976, reverted to grazing. In 1982 the Scheduled area was enclosed by a wire fence with buried rabbit wire. The fence not only proved ineffective, but the lack of grazing within the enclosed area actually encouraged rabbit activity. All fencing was therefore removed from the vicinity of the building in the late 1980s. Outwith the Scheduled area, the field was used for various recreational events, which involved activities such as the erection of marquees stabilised by pegs penetrating the ground 0.5m or more, or the display of heavy agricultural machinery.

In 1991 Warren Field was shallow-ploughed to reseed the grass and a programme of fieldwalking was undertaken; no prehistoric material was recovered (Begg and Hewitt 1991). A geophysical survey undertaken in 2000 by students of Glasgow University Archaeology Department appeared to show the outline of the building (Jones 2000). However, there was no clear understanding of the level of preservation of the known archaeological features and given the vicissitudes suffered by the building since its discovery, and the fact that the field was known to have been in cyclical cultivation since at least the late eighteenth century, damage might have been considerable. The NTS therefore established a project to assess the condition of the pit alignment and the building, and to evaluate the nature of the other cropmark features within the field.

The project also sought to address various research objectives. Pit alignments are rare in northeast Scotland; additionally, the class itself is not well understood, as it includes monuments varying widely in scale, nature, function and date (from the Neolithic to the early modern period), of which too few have been excavated to refine the picture. Rectangular timber structures are also rare in the cropmark record in northeast Scotland and more generally in northern Britain and although the Warren Field structure superficially resembled two other excavated sites interpreted as roofed Neolithic buildings – Balbridie (Fairweather and Ralston 1993) and Claish Farm, Stirlingshire (Barclay, Brophy and MacGregor 2002) – there were suggestions that it might equally represent the lowland element of medieval rural settlement, another elusive feature within Scottish archaeology. At the same time, understanding of the relationship of rectangular timber halls to other, more ephemeral, early Neolithic settlement evidence in Scotland, including potential turf and/or timber-built structures, is very limited. The occurrence of two such enigmatic monuments as the pit alignment and the hall in close proximity, alongside a series of other cropmark features, provided an opportunity to explore such issues at a landscape scale.

Figure 1. Location of the Warren Field site. Map 1 shows the site in relation to the river Dee and the rising ground to the west. The Mesolithic and Neolithic site at Garthdee and the Mesolithic sites at Chest of Dee and Glen Geldie are also marked. Map 2 shows Warren Field in relation to the Neolithic hall at Balbridie, the Mesolithic site at Nethermills and the small Neolithic sites at Crathes Castle Overflow Car Park and Milton Wood (this report). Map 3 shows the excavated areas (Based on the Ordnance Survey map © Crown Copyright NTS licence No. 100023880)

A small evaluation excavation was undertaken in 2004 (Murray and Murray 2004). Ploughing had truncated the site so that only negative features survived, cut into the underlying sands and gravels. Topsoil was removed by hand to evaluate finds distribution in the cultivated ground. A second resistivity survey was carried out over the site of the building, directly before excavation (Kidd 2004). Comparison of the excavated plan with the results of the 2000 and 2004 surveys was disappointing and emphasizes the difficulties encountered in the interpretation of geophysical data in a glacial geological context. As a result of this evaluation, the full plan of the timber structure was exposed – by now confirmed as an early Neolithic building – and more of the pit alignment was excavated (Murray and Murray 2005a). Samples from the pit alignment taken in 2005 indicated that it had been in use from the Mesolithic. To confirm this dating, two further pits in the alignment were sectioned and sampled in 2006 (Murray and Murray 2006). Extensive evaluation of the wider cropmark complex was undertaken in 2005 and 2006. In both of these seasons, the topsoil was machine-stripped with a flat-edged ditching bucket. The excavation was undertaken by Murray Archaeological Services Ltd on behalf of the National Trust for Scotland.

Archive

All archive material will be deposited with the National Monuments Record of Scotland, Edinburgh at the date of publication. The finds have been deposited in Marischal Museum, University of Aberdeen.

1.2 Geomorphic setting

Warren Field is a flat surface at c.55m OD. To the west and north the ground rises in a gentle slope in bedrock. To the east the deeply incised narrow gorge of the Coy Burn, 10–15m below the terrace surface, receives water draining the Loch of Park, 4 kilometres to the northeast of Warren Field. The terrace forms the surface of an unknown thickness of sands and gravels (Fig. 1); around 2m of gravel are poorly exposed in the sides of the Coy Burn. The terrace fill is very probably of glacifluvial origin, though the terrace is higher and thus older than those mapped along Deeside by Brown (1992).

The aerial photograph (Fig. 2) shows two sets of geomorphic features marked by dark, slightly damper channels on the otherwise very well-drained terrace surface. These features are not all identifiable morphologically. The first set of channels (marked A to C on Fig. 2) are generally longer, east-west trending channels. The two parallel channels at extreme left seem to split to leave a very low ridge of pale sand, and the ridge is possibly a mid-channel bar. This ridge, not distinguishable topographically today, was the locus for the pit alignment. The channels marked D TO G in Fig. 2 are parallel, more deeply entrenched in the terrace surface, and flow from north to south, widening slightly downslope. Channel C in the middle of the field seems to lead to channel F, suggesting that water flowed for a time contemporaneously in both sets of channels but it is thought that channel C is intercepted by channel F, making channel F later, and channels A–C are thought to predate channels D–F.

There is no direct dating of the channels: no channel examined contained organic matter that could be radiocarbon dated. Archaeological features tend to be formed, or are more easily seen, on what are now drier patches of sand or gravel, but at Warren Field it is not thought that these features were situated to avoid flowing water, as none of the channels is thought to have been active when the archaeological features were made. Channels A–C are aligned with the general trend of glacial meltwater channels along Deeside (Brown 1992), and do not accord with the current southerly slope to the River Dee (Fig. 1). Channels A–C are likely to be of Late Devensian age, formed during deglaciation (Brown 1993). Channels D–F cut into the terrace surface and flow to the incised Coy Burn (Fig. 1). They are likely to have been active when the Coy Burn was downcutting. This period is not known with precision, but since the Coy Burn has an alluvial fan at its outlet leading to one of three glacifluvial terraces of the Dee at Milton (Brown 1992), it is likely that these channels are also of Late Devensian age.

Figure 2. Aerial photograph of the Warren Field taken in 1976. The hall and pit alignment are marked. Letters A–G refer to the report on the geomorphic setting of the site (© Crown Copyright: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Image KC 632)

It is probable that the terrace surface was more topographically differentiated in the early Holocene period because much soil redistribution and surface smoothing has occurred in recent centuries. The early Mesolithic pit alignment follows closely the line of the probable gravel bar between channels A and B, and it may be that in the early Mesolithic period this ridge was still topographically distinctive between two shallow but dry channels. The Coy Burn had probably by this time become a major entrenched gorge to the east.

By the early Neolithic period when the timber hall was constructed, channel C (Fig. 2) may still have been visible as a shallow dry channel. This seems to curl round the site of the hall, and may have been used to demarcate the site.

Chapter 2

A line in the landscape: the pit alignment circa 8210–3650 cal BC

2.1 The excavated evidence

The aerial photographs (Fig. 2) taken in 1976 reveal a line of pits extending northeast/southwest along the top of a very low ridge. Between 2004 and 2006 a total of 12 pits were revealed in plan (Fig. 3: Features 20, 19, 18, 16, 22, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 and 12), extending for a distance of c.50m. There were also a number of smaller features interpreted as post-pits (Fig. 3: Features 21, 17, 2, 3, 4, 8 and 13) which were not visible on the aerial photographs. Detailed examination of the aerial photographs suggests that the line may extend to the southwest with two additional pits and to the northeast with two, possibly three, features of similar size to the excavated pits, but at slightly greater spacing. If these features belonged to the alignment it would have been c.90m long. Any further extension to the northeast, if it existed, would have been removed or obscured by boundaries within the eighteenth-century designed landscape. However, it must be stressed that the field has been in intensive use over the centuries and other anomalies visible on the aerial photographs have ranged in date from prehistoric to modern (see chapter 4.1). It should also be noted that if these other features were part of the alignment, the line would not appear to run so clearly along the low ridge, but to veer off at the northern end.

The line of the excavated pits was not completely straight as there is a distinct curve towards the east at the southern end (features 18–21) and, although a straight line can be drawn between pits 16 and 12, pit 6 lies to the east of this line.

The pits

In 2004, topsoil was removed partly by hand, to reveal the pits between pit 5 and post pit 13. The pits had been cut into very hard, compact silty gravels, below which there were bands of finer, sandier gravels. Pit 5 was partially sectioned in 2004 but, due to very dry conditions, even with spraying, the primary fills of redeposited gravel were indistinguishable from the undisturbed natural gravel and only the secondary fills were excavated. When pits 5 and 6 were fully excavated and the surface of pit 7 re-exposed in wetter conditions in 2006 they were shown to be far larger than first thought. It is probable that pits 9, 10, 11 and 12, which were planned in the dry conditions of 2004, are actually larger.

Seven of the pits and five of the smaller features were fully sectioned and are described in detail below. They ranged in size from c.1m in diameter and 0.55m deep to 2.6m in diameter and 1.3m deep. All of the sectioned pits proved to have had an initial cut partially filled by eroded material and slumping of upcast material. Subsequently each of the pits had been recut. All of the pits had been truncated by ploughing. Samples were taken of primary and secondary fills and datable material identified where possible. The sample locations are marked on the pit sections (Fig. 3). In total, 17 radiocarbon samples from the pits have been dated. For a full discussion of the radiocarbon dates see Marshall (chapter 5). The samples from three pits (16, 18, 19) were from charcoal deposited in the base of the pits and can confidently be used to say that these three pits were dug in the Mesolithic in the first half of the eighth millennium cal BC. Pits 18 and 19 were dug first and pit 16 some 200 to 400 years later. The dates from primary fills in pits 5, 6 and 22 are from contexts that do not allow the same degree of certainty as they contained material that had eroded into the pits. However, as there is a correlation between the soil chemistry of the primary ...