eBook - ePub

The Annoying Difference

The Emergence of Danish Neonationalism, Neoracism, and Populism in the Post-1989 World

- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Annoying Difference

The Emergence of Danish Neonationalism, Neoracism, and Populism in the Post-1989 World

About this book

The Muhammad cartoon crisis of 2005?2006 in Denmark caught the world by surprise as the growing hostilities toward Muslims had not been widely noticed. Through the methodologies of media anthropology, cultural studies, and communication studies, this book brings together more than thirteen years of research on three significant historical media events in order to show the drastic changes and emerging fissures in Danish society and to expose the politicization of Danish news journalism, which has consequences for the political representation and everyday lives of ethnic minorities in Denmark.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Methodological Framework and Historical Context

CHAPTER 1

The Emergence of Neonationalism and Neoracism in the Post-1989 World

On the one hand, I agree with scholars like John Comaroff, who argues that there can be no universal theory of nationalism and ethnicity (1996); yet as Comaroff’s work shows, there can still be studies of the regularities inferred inductively through substantial case studies. On the other hand, this should not be misunderstood to mean that we can’t use generalized insights such as Comaroff’s own, or Cas Mudde’s studies of radical right populism from a more detached theoretical perspective (2007), or Arjun Appadurai’s conceptualization of anxiety of incompleteness, nationalism, globalization, and related issues (2006). These three examples may help us look for regularities in the local case studies, even if they are not borne out of these case studies, or in the end may be revised or even rejected from more local studies—studies that of course encompass both the global and local in various relationships.

From Danish Nation-Building to Neonationalism

The prefix “neo” in this context indicates a revitalization of nationalism in the post-1989 world. This nationalism occurs within an established nation-state and differs from the nation building in Denmark that took place in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. That process began among Copenhagen’s emerging bourgeoisie, which had acquired some wealth and education during the relatively peaceful and economically prosperous eighteenth century but which saw the king and the aristocracy firmly in power, with German assistance. Grundloven (the constitution) was passed in 1849, ending absolute monarchical rule. A few years later, in 1864, Denmark was defeated in yet another war with Germany. By then the country’s loss of territory included Norway (in 1814), Sleswig, Holsten, and Lauenborg; 170,000 Danish speakers now lived outside Denmark. For the first time, almost all of those who lived within Denmark’s borders spoke Danish. In 1920 most of the Danish speakers located on the German side of the border returned when the lost territory in southern Jutland was voted back in a referendum. The referendum came as part of the negotiations of borders following Germany’s defeat in World War I, and ended up moving the national border farther south, reflecting the linguistic border as closely as possible.

During the last third of the nineteenth century, nation-building efforts spread from the elite to the peasants, workers, and smallholders. Unlike in neighboring Sweden, the Danish popular movement of peasants and workers created a separate public sphere and a civic society independent of the state, which stemmed from the nation’s failure to establish norms for all citizens. Danish nationalism at the time was motivated by the hostile relationship to Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s Germany but was mainly aimed at gaining social and political power within the country. In Sweden social democrats pursued nation-building through a modernist utopian ideal by uniting popular movement and the state (Hansen 2002; Trägårdh 2002).

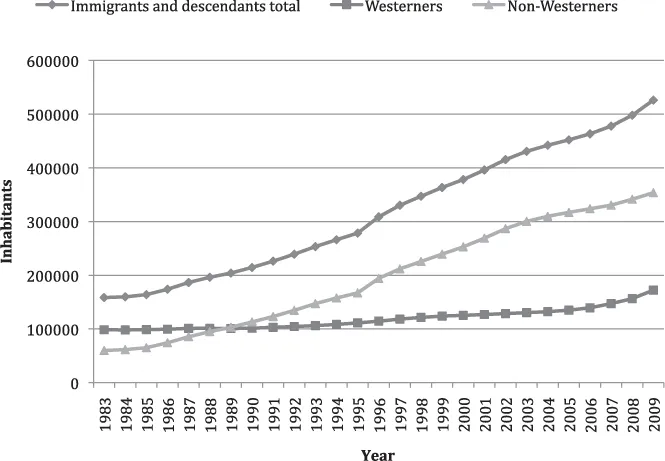

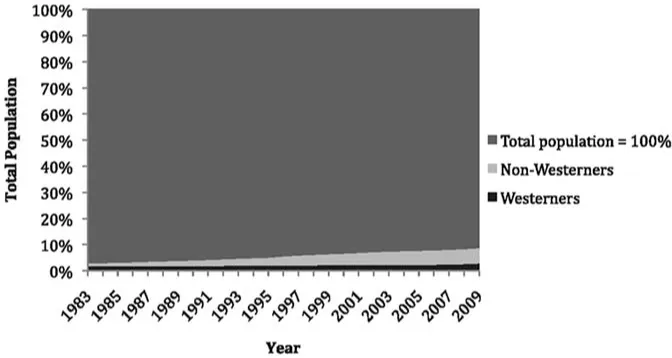

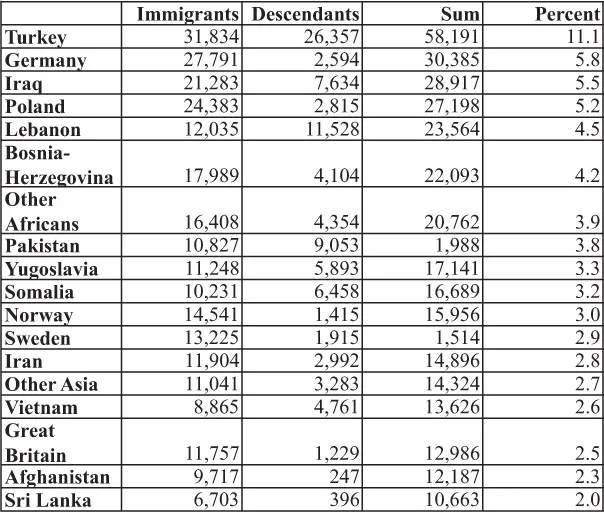

In the late 1960s a new migration began taking place: unskilled laborers from outside Europe (and ex-Yugoslavia) were invited to work in the Western European industry (see figures 2 and 3, and table 1). As elsewhere, this migration provided the impetus for a new understanding of the concept of culture. “Cultural difference” soon came to refer to the differences displayed by these new (guest) workers and their families. Although the migration was formally halted in 1973, the number of migrants kept growing steadily in Denmark throughout the 1980s and 1990s as family members joined each other under the Family Reunification Act. These migrant workers and their families were represented fairly positively in the media until the late 1980s.

Figure 2. Immigrants and descendants in Denmark by 1 January 1983–2005

Source: Ministry of Refugees, Immigration, and Integration Affairs (2009: 16)

Figure 3. Percentage of Western and non-Western immigrants and descendants of total population by 1 January 1983–2005

Source: Ministry of Refugees, Immigration, and Integration Affairs (2009: 17)

Table 1. Immigrants and descendants according to country of origin

Source: Ministry of Refugees, Immigration, and Integration Affairs (2009: 13)

In 1984, refugees from the Middle East fleeing the protracted conflict between Iran and Iraq (1980–88) arrived in Denmark. They were placed more or less arbitrarily in buildings that were being abandoned. In Kalundborg, a town 100 kilometers west of Copenhagen, about sixty Iranians lived in an old hotel building surrounded by both bars and private homes. On 26 July 1984 native Danes attacked the shelter, throwing bottles through the windows and trying to enter the building. According to the television news coverage, the mere sight of refugees with new bicycles provided by the authorities was provocative (Togeby 1997: 8–9). Television reported how the provoked Danes directed their anger at the refugees, but they did not pay attention the authorities handing out the bicycles.

In 1985, Mogens Glistrup, the leader of the Progress Party, got out of prison after finishing his sentence for tax fraud. Glistrup had started a populist party in 1972 and had won a unprecedented 15.9 percent of the votes (28 seats in the 179-seat Parliament), based on popular discontent with the tax system as its key issue. From a populist perspective the party was unique, since it did not include nationalist appeals (J. Andersen 2004: 148–49), but relied on a tax rejection scheme. On his return to the political scene, Glistrup began to use an ever more anti-Islamic platform to attract voters, and in the process he turned to nationalist recruiting for party support. Although he was isolated within the party and was finally expelled in 1991, he is an important historical figure in terms of constantly putting Islam on the media’s agenda and for his populist appeals. Glistrup preferred the offensive categorization “Muhammedanians” (muhammedanere) rather than Muslims, yet his racist communication also targeted black Africans, particularly Somalis; his Web site featured a page of racist jokes about Somalis.

Another historical figure, radical right-wing priest Søren Krarup, wrote for years in Morgenavisen Jyllands-Posten. When the editorial leadership changed in 1988, Krarup no longer had direct access to the paper’s pages, but he had already made major news in 1986. Tabloid newspaper Ekstra Bladet called him “an apostle of evil,” a label that grew out of Krarup’s 1986 initiative to oppose a national door-to-door collection of contributions for the Danish Refugee Council. He chose this occasion to launch an attack regarding Danish refugee politics, calling for national resistance to hold the borders against foreign refugee “invasion” caused by “elite traitors.” Krarup made his campaign public through advertisements in Jyllands-Posten and received enough economic and political support to establish the Committee against the Refugee Act of 1983, later changed to the Committee against the Policy on Integration (Komitéen mod Indvandrerpolitiken). This committee became the core of radical right-wing group the Danish Association (Den Danske Forening), made up of members with xenophobic, nationalist, populist, and anti-Islamic convictions and agenda. They regard the association as a new resistance movement, directly comparable to the resistance against the Nazi occupation of Denmark from 1940 to 1945, and against traitors—those who supported the occupying troops. Members included leading politicians in the Progress Party and the later Danish People’s Party, Pia Kjærsgaard (MP), who led the party while Glistrup was in prison: Søren Krarup (MP), Glistrup’s cousin; priest Jesper Langballe (MP); Søren Espersen (MP); and several others. The Danish Association, a Christian-oriented “Tidehverv” (epoch), a journal of the same name, and the Progress Party were four vehicles via which the far right cultivated the intimate relationship between Danishness, nationalism, Christianity, anti-immigration, anti-Islam, and populism that developed in the early 1990s.

Though the origin of these new calls to secure the Danish borders, values, identity, and language can be heard with increasingly louder voices in the late 1980s, the prefix “neo” only began to become a historical factor in the early 1990s in the wake of international mega-events, not least the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and processes of globalization.

The Post-1989 World

Hastings Donnan and Thomas Wilson have described what they call the “startling world transformations” since 1989: the dismantling of the Iron Curtain and the fall of the Berlin Wall (the border between the two competing world systems of capitalism and communism); the disintegration of the Soviet empire and state (with the reawakening of new states); the dissolution of Yugoslavia (with fierce redrawing of borders); the Gulf War (with its new alliances and information warfare); the expansion of the European Union and the formation of the “Inner Market” (with disappearing internal borders and new external ones); and peace accords in the Middle East and Northern Ireland (Donnan and Wilson 1999). In this post-1989 world or, as Comaroff (1996) terms it, this “age of revolution,” borders weakened, only to be replaced by new ones that were even stronger.

On top of these events comes globalization of culture, society, and technology—for instance, the global introduction of the World Wide Web in 1989 as a freely usable technology; the growth of multinational corporations; new supranational trading blocs, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994; and environmentalist concerns, both as supra-border threats and as fuel for social movements (e.g., the Chernobyl fallout in 1986). The Chernobyl radiation disaster on 26 April 1986 and the following days knew no national borders. Even people such the Sami reindeer herders, more than a thousand kilometers away, were affected: They were forced to butcher their herds in August (Blackwell 2003). Such events involved people with vulnerable forms of subsistence and borders that failed to provide safety.

Any drastic change may produce shared emotions that can be capitalized upon at any given moment. According to Anthony Giddens (1987: 178), “[T]he significance of nationalism in the modern world is quite clearly related to the decline of tradition and to the fragmentary character of everyday life in which lost traditions are partly refurbished.” The experience of fragmentation of day-to-day life may impinge upon what R. D. Laing called “ontological security” (1968), the sense of being at home in one’s being and thereby able to meet the hazards of life. Whereas Laing used the concept in an individualized sense, I would apply it more generally to the shared sense of security, or even the shared imagination of insecurity, resulting from the dramatic transnational changes reported by the news stream and its expert interpreters. As such, ontological insecurity relates to “human security,” an underdeveloped concept pointing to on-the-ground security rather than the security connected to the nation-state, which refers to the right to be protected from chronic threats, such as disease and hunger, and sudden disruptions of everyday life. The sense of insecurity may have arisen in Denmark, although I don’t want to exaggerate or be too specific about the character of this potential fertile ground for becoming a political or commercial platform. One aspect of the social anxieties that can emerge in the post-1989 world of disappearing borders and a bigger mix of newcomers, strangers, and natives is the mixophobia and proteophobia Zygmunt Bauman talks about. If “proteophilia” is the love, desire, and enjoyment of change often associated with the city, “proteophobia” is the opposite: the feeling of being endangered and threatened by not knowing what may happen and what to expect when one is in a big city. Likewise, if the pleasure of constantly mixing and mingling with strangers is “mixophilia,” then Bauman calls the opposite “mixophobia,” the off-putting and frightening experience of being completely surrounded by strangers, those “moments of fright” when people find them themselves in a crowd, surrounded by strange faces (Z. Bauman 2004). “When you visit unfamiliar places, you want to insure yourself against such moments; as a tourist, you are careful to keep to the narrow and well protected paths provided for the tourists’ use. You don’t mix with the local population. If you meet the local people, they are mostly the waiters, hotel maids and bazaar traders,” according to Bauman (2004: 4). This may be unlike the committed ethnographer, the “mixophiliac” who seeks precisely those moments of total absorption. Again, my point is not to describe causes and effects or to characterize emotions leading to action, but rather to describe some of currents in this turbulent post-1989 phase, for emotions can become the object of self-reflection and the potential target of groups aiming to mobilize supporters and consumers.

A clear shift in Swedish newspapers’ presentation of issues concerning migration and migration policy occurred in the late 1980s, from a largely positive view of migrants to a view of migrants as a cultural, political, social, and economic threat to the Swedish host society (Fugl 1997). Hanne Fugl’s data suggest that even though the assassination of prime minister Oluf Palme in 1986 may have contributed to this shift, international events and processes are the most feasible explanation for it, given that similar patterns can be found in countries such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom and that all of these patterns revolve around 1989 (Fugl 1997).

Elsewhere in Europe, perceptual turns took place. Within the year 1989, linguist Ruth Wodak noted that rhetoric and perceptions in Austria changed significantly. Following the democratic revolutions in East Central Europe, refugees from the behind the Iron Curtain had been welcomed as heroic refugees fleeing tyrannical regimes, but now suddenly they became socially more threatening “economic immigrants,” “spirit and salami merchants,” and “criminals” too lazy and selfish to remain in their own country and solve their own problems (Wodak 1997: 133).

Following the dramatic events around 1989, Europe in 1990–91 witnessed a drastic increase in racially motivated violence and polarized attitudes toward immigrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers. For instance, in September 1991, in the Saxon town of Hoyerswerda in the former East Germany, skinheads and neo-Nazis attacked guest workers and asylum-seekers (Peck 1995: 103). Such events were met by demands for tougher policies restricting the number of non-Westerners coming into Western Europe and stricter requirements for those already within the European Union. Leading politicians warned not only about insecure Russians in endless rows of trabants but also about hordes of disillusioned Africans threatening the “safety” of the Western European middle class; these “threats” were used to provide strength to the idea of the newly expanded “Fortress Europe,” with its vanishing internal and fortified external borders. Thus Italian Secretary of State Gianni de Michelis warned in 1990, “We must be careful that these two or three million refugees do not become 10 times as many, since this type of invasion [from Eastern Europe] would create a terrible destabilization” (H. Rasmussen 1996: 47).

Borders, national ones in particular, are supposed to provide comfort and security for their citizens. After 1989, borders began to collapse and became an existential matter. The nation-state entered into a temporary crisis caused by the expansion of the economic market, the free flow of capital over the borders, and freer mobility of workers within the European Union, which meant that national economies could no longer be tied to production, trade, and consumption (Comaroff 1996). When the nation-state is in a crisis, agents of the nation-state, or self-staged agents acting on behalf of state, react with new nationalistic appeals: “The people” make ownership claims to the territory where they are living and act to exclude any who are not considered part of this people.

Before I deal with the analytical balance of neonationalism and neoracism, it is necessary to look at the war engagement in Afghanistan in the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union, because this is where the “clash of civilizations” narrative is born.

Changing Enemies

According to Steve Coll, President Jimmy Carter and his National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski allowed the CIA in 1979 to begin supporting Muslim militant groups on the southern border of the Soviet Union in order to create an anarchic frontier that would make it difficult for the Soviets to make encroachments into the oil-rich strategic Middle East (2007). When Ronald Reagan became president in early 1981, support to Muslim rebels on the border, including militant Muslims and others in Afghanistan and in Iraq, increased dramatically. This support went hand in hand with Saudi Arabia’s support of several thousand Saudis (including Osama bin Laden) and others,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- List of Acronyms

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I. Methodological Framework and Historical Context

- Part II. The Campaign(s) of 1997

- Part III. The Mona Sheikh Story of 2001

- Part IV. The Muhammad Cartoon Crisis

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Annoying Difference by Peter Hervik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.