![]()

1

INTRODUCTION: MEDIA ANTHROPOLOGY IN A WORLD OF STATES

The present world is a world of states, neither a world of tribes nor a world of empires, though the remnants of such forms are still present and occupy part of our thinking.

Nicholas Tarling (1998)

We live in a world of states. We have lived in such a world since the dismantling of the British and French empires after the Second World War. The remnants of both empires are still present, but the influence of Britain and France has waned as steadily as that of the United States, China, India and other large states has grown. In the 1990s, the now global inter-state system penetrated deep into the former Soviet bloc (the last European empire) and into non-aligned Yugoslavia. The result was a host of post-socialist states, some of which have joined the European Union – a curious entity at odds with the statist logic of the global system (Tønnesson 2004). By 2004 the misleadingly named United Nations had recruited a record number of 191 member states. Together with other global institutions, the UN actively supports the present state system. By the same logic, these institutions and the powers that bolster them strongly discourage secessionism. Thus between 1944 and 1991 only two territories around the world – Singapore and Bangladesh – managed to secede from recognised states and join the United Nations (Smith 1994: 292). Many other secessionist attempts were thwarted during that same period, as they still are to this day.

This book examines a neglected aspect in the study of this world of states: how states use modern media to ‘build’ nations within their allocated territories. The case study is Malaysia, a state created in 1963 as part of a third, Afro-Asian wave of modern state formation. The first wave broke upon the Americas in the nineteenth century, the second across Europe in the twentieth century, and we have recently experienced a fourth, post-Soviet wave (O'Leary 1998: 60).

The Federation of Malaysia was initially an amalgam of four British colonies: Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo (Sabah). Whilst Singapore seceded in 1965, the other three territories have remained united, and further separations seem highly unlikely. Malaysia's birth was inauspicious: it had inherited an economy wholly dependent on export commodities and a deeply divided multiethnic population. The new country faced the immediate threats of civil war, a belligerent Indonesia, and Filipino claims over Sabah. As I write these lines in mid-2005, Malaysia is a stable polity with a prosperous economy, a quasi-democracy, negligible levels of inter-ethnic violence, and amicable relations with neighbouring states. In an era of ‘failed states’ and ethnic massacres, how can we explain Malaysia's undoubted success? What are the domestic and external factors that have contributed to Malaysia's survival and prosperity?

A comprehensive account of all the possible contributing factors is beyond the scope of this book. Instead, the present study concentrates on a single domain of state intervention – the media – and on a single Malaysian people – the Iban of Sarawak, on the island of Borneo. What we lose in scope, we gain in focus: by studying in detail Iban uses of state media over time, we can gain an appreciation of analogous processes in other parts of Malaysia and elsewhere.1 I argue that state-led media efforts have been amply rewarded, for the Iban of Sarawak have become thoroughly ‘Malaysianised’. I also suggest that the Iban experience has important implications not only for anthropologists, development experts and indigenous activists, but also for our understanding of media in a world of states. I study four foundational media forms common to modern states virtually everywhere, namely state propaganda, writing (literacy), television, and clock-and-calendar time. In the developed North it is easy to forget that even the latest media technologies rely on earlier – but by no means superseded – media. For instance, both email and mobile telephone messaging depend on writing and clock-and-calendar time. New media rarely replace old media; the two usually co-exist.

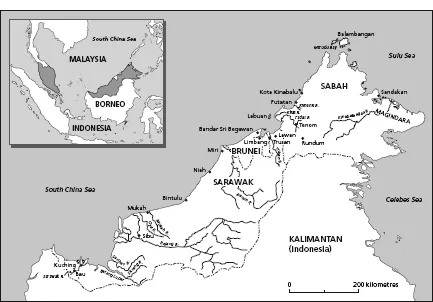

Figure 1.1. Sarawak, Sabah and Peninsular Malaysia.

Source: adapted from Andaya and Andaya (1982).

This chapter provides a theoretical background to the book. In the following section I clarify my usage of terms such as state, nation, nation-state, nation building, and nation making, and suggest that ‘nation building’ is still a concept with social scientific validity. I then define this study as an ethnological contribution to a research area known as ‘media anthropology’. My approach is ethnological in that it tracks the intertwined fates of the Iban and other Malaysian peoples (ethnos) across time and space through concepts such as diffusion, appropriation, cultural form, media form and culture area. In this respect, it differs from social anthropological (ethnographic) studies centred on the embedded sociality of contemporary groups. I suggest that Malaysia is becoming a ‘thick’ culture area in its own right, distinct from both the Indonesian and Singaporean culture areas, and that the consolidation of Malaysian variants of global media forms is central to this process. This consolidation entails what I call ‘sustainable propaganda’, i.e., state propaganda fully assimilated into the life and institutions of a population. The chapter ends with an outline of the book.

Nation Building

There is broad agreement amongst scholars on the meaning of the term ‘state’. In the contemporary world system, a state is an independent territory recognised by the United Nations, e.g., East Timor, Germany, or Canada. It is ‘the major political unit in world politics’ (Connor 2004: 39). In this book I use the term state interchangeably with the more colloquial ‘country’.

Defining the term ‘nation’ is far more problematic. A vast literature has been devoted to this problem, which has acquired renewed urgency with the demise of the Soviet Union and the expansion of the European Union. As is often the case, no consensus has been reached on the matter. The debate is closely linked to the inter-disciplinary study of nationalism. Two broad camps have formed on the question of origins: those who argue that nations are modern creations arising from the Enlightenment and industrialisation and those who trace the roots of nations to Antiquity or even further back.

The first position – modernism – is commonly associated with Ernest Gellner (1983), the Czech-Jewish philosopher and anthropologist. Other influential modernists, also known as ‘constructivists’, are Anderson (1991 and below) and Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983). For Gellner (1983: 140-143), the ideology of nationalism was the result of the economic modernisation of nineteenth century Europe. Industrialisation demanded a realignment of culture and state. The new economy could only develop if the population learnt to communicate fluently across ethno-linguistic divides, both face-to-face and through abstract media. The driving principle was ‘one state, one culture'. Under these circumstances, most European states developed national languages and mass educational systems. The aim was to create a ‘literate sophisticated high culture’ that could cope with the demands of economic modernisation. As a result of these changes, some ethnic groups began to feel excluded from their polities and to demand autonomy in their ‘own’ homelands. The simple doctrine of self-determination became a rallying call across Europe and eventually the whole planet. This doctrine demanded that the governing and the governed be co-nationals (O'Leary 1998).

The second position has a strong advocate in A.D. Smith (1986, 2001, 2004), a proponent of the ‘ethno-symbolist’ theory of nationalism. A nation, for Smith, is a

named human population which shares myths and memories, a mass public culture, a designated homeland, economic unity and equal rights and duties for all members (Smith 1995: 56-57).

Smith contends that although many of the ideals of nationalism are indeed modern, the roots of nations such as England, France or Japan can be traced to ancient times. Nations are not built out of thin air; they have solid ethnic foundations, myths of ethnic origin and election, and symbols of territory and community (Guibernau and Hutchinson 2004). They are patterned on, and often have evolved from, dominant ethnies, or ethnic communities. Yet the obdurate ‘presentism’ of modernist scholars, says Smith (2004), leads them to focus on elite manipulation, downplaying processes of national formation over the longue durée.

One criticism levelled at Smith is of special relevance to the present study. Connor (2004: 41) takes exception to Smith's questioning of the nation as a mass phenomenon, a questioning that contradicts Smith's own definition of the nation just quoted. To Connor, the notion of nation must necessarily imply ‘a single group consciousness’ that unites the elites and the masses. Such a consciousness cannot arise overnight; it requires many generations to spread from the elites to the masses. This poses a formidable methodological challenge for historians of nationalism, adds Connor, for illiterate masses are invariably ‘silent’. It is here, I would suggest, that an ethnological approach can make a lasting contribution, in that it combines ethnographic and historical research. Thus the present work springs from a direct fieldwork engagement with, and historical work on, both the Iban ‘masses’ and the elites.

Both Smith's and Gellner's theories suffer from weaknesses, but they also have much to recommend them. Gellner's linking of nationalism with modernisation is highly pertinent to Southeast Asia, a different region and historical period from those central to his thesis. As I explore in chapters 3 and 4, Iban and other Malaysian elites have used media to ‘modernise’ the Iban through cultural standardisation under conditions of rapid economic growth. Smith's definition of the nation, on the other hand, captures succinctly the aspirations of Malaysia's nation builders, including most rural Iban leaders, teachers and schoolchildren. These varied social agents all hope that Malaysia will achieve full nationhood by the year 2020. There is an important caveat, though: there is no provision as yet for Malaysia's ethnic Chinese and Indians to be given rights equal to those enjoyed by the Malays – the dominant ethnie (see chapter 5 and conclusion).

The notion of ‘nation building’ is no less problematic than that of nation. This term has long been marginalised from serious Western social theory for its association with modernisation theory (Smith 2004: 195, cf. Deutsch and Foltz 1963, Deutsch 1966). The latter had its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, as the U.S. government recruited scores of social scientists in its efforts to win the ‘hearts and minds’ of Third World populations in rivalry with the Soviet Union and China. Modernisation became an elastic notion used by U.S. academics and policy-makers to explain the persistence of traditional ‘mind-sets’ and ease the transition to market-driven, ‘democratic’ regimes in the postcolonial world. In other words, it was used to promote a form of nation building modelled on an idealised United States (Latham and Gaddis 2000). In Vietnam, ‘the other war’, the propaganda war over hearts and minds, was fought and lost by American social scientists who failed to agree on a nation building strategy for that country (Marquis 2000). At present, the term is often used in the Anglophone media and popular scholarship with reference to America's half-hearted attempts at ‘reconstruction’ in occupied countries such as Afghanistan or Iraq (e.g., Ignatieff 2003).

Given its pedigree, it is little wonder that anthropologists and other social scientists are wary of the term ‘nation building’. One recent search for an alternative term has been Foster's (1997, 2002) work on media and ‘nation making' in Papua New Guinea (PNG). In his monograph Materializing the Nation, Foster (2002) argues that although PNG inherited a weak state from the Australian colonists, the making of a PNG nation is well under way. Foster's notion of nation making differs from that of nation building in that it does not privilege state-led processes of change. In addition to the state, this notion directs our attention to the private sector and the wider population. Foster finds compelling evidence that PNG, independent only since 1975, is already far more than an ‘imagined’ political community (Anderson 1991). He analyses Coca-Cola advertising, law and order campaigns, letters to the English-language press, millennial cults, betel nut chewing and other practices, and reports the emergence of a distinctly PNG public culture. Foster follows Billig (1995) in stressing the significance of banal everyday practices in the maintenance of a national public culture, whether they be reading the PNG weather forecast or viewing street hoardings in Tok Pisin, the national language.

There are good reasons, PNG notwithstanding, to retain the term ‘nation building’. First, in contrast to PNG, Malaysia inherited a strong state from its colonial rulers. Efforts to create a Malaysian nation began in the early 1960s and are still given priority by the government. The state was, and remains, the most powerful agent of social and cultural change in Malaysia -as in many other countries. Second, Malaysian state propaganda on security, development and national integration soon percolated even into remote rural areas and began to shape people's worldviews, as I show in chapters 3 and 4. Today official nation-building propaganda is hardly distinguishable from the views of Iban from all walks of life. Third, the term nation building is still widely used by the ‘beneficiaries’ of America's Cold War largesse: the elites and middle classes of postcolonial states around the globe. It is also routinely used by inter-state organisations (the UN, World Bank, Commonwealth, etc.) and the media in relation to ongoing development strategies for East Timor, Afghanistan, Iraq, South Africa, and so on. The term captures the built nature of modern state and nation formation (Kolstø 2000). The close relationship between metaphors of development and building is clearly seen in the etymology of the Malay and Indonesian word pembangunan (development), derived from the term bangunan (building, structure). In the contemporary world, there is the universal expectation that a built infrastructure consisting of roads, airports, schools, hospitals, etc., will be put in place. Without such an infrastructure, not only is a country deemed underdeveloped, it cannot possibly operate in a capitalist world economy (Tønnesson 2004). A concomitant requirement is the existence of a mass workforce; a nomadic band of fifty hunters and gatherers can build neither a state nor a nation (Diamond 1999). In sum, the term nation building both reflects and produces socio-economic realities. It has tangible effects on the world, often unintended ones, but far-reaching all the same. All this lends the term enormous practical and theoretical importance in a world of states. Whilst not denying that the concept of nation making has great analytical potential, in this study I deal primarily with state media interventions that fall under the rubric of ‘nation building’.

A final word on the term ‘nation-state’. Strictly speaking, a nation-state is ‘that relatively rare situation in which the borders of a state and a nation closely coincide; a state with an ethnically homogeneous population’ (Connor 2004: 39). The term should be used sparingly when referring to present-day countries, but it is worth remembering that the nation-state as an ideal is still well entrenched in many corridors of knowledge and power, not least amongst politicians and social activists in Malaysia.

Media Anthropology

This book is intended as a contribution to a research area known as ‘media anthropology’, the anthropological study of contemporary media (Askew and Wilk 2002, Ginsburg et al. 2002).2 Like the study of nation building, the early history of media anthropology is tightly bound up with American foreign policy. Early functionalist fieldwork on media in small town America gave way during the Second World War to the study of enemy and allied media as part of the war effort (Mead and Métraux 2000). Some of the world's leading anthropologists, including Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict, studied national cultures ‘at a distance’ through films, novels and other media produced in enemy countries they could not visit owing to the war. After the war, interest in the media diminished as anthropologists returned to field research. There was scant anthropological interest in the media until the late 1980s, which saw the onset of a rapid growth in the number of studies that has continued unabated into the early years of this century (Peterson 2003).

Just as post-war anthropologists lost interest in the media, mass communications researchers in the U.S. became increasingly concerned with the effects of media (Morley 1992: 45). Their approach was often behaviourist. It assumed that mass media could ‘inject’ a positive ideology directly into the populace – the so-called ‘hypodermic needle’ model. This optimistic model, like its pessimistic precursor from the Frankfurt School, presumed a passive, atomised audience unable to resist the allure of the mass media. The model proved popular with modernisation theorists working on nation building projects within America's sphere of influence in the Third World (Peterson 2003: 44). It sustained the modernist ideology of the early Cold War through wellfunded research and journals prone to scientistic jargon. At the same time, it failed to address critically questions of power, knowledge or economy (Lull 1990: 15). But a reaction against this mass communications ‘dominant paradigm’ was already under way in the 1960s. It came to be known as ‘uses research’. If effects research had asked ‘what media do to people’, uses research asked ‘what people do to media’. Its theoretical orientation was structural-functionalist. People were seen as active participants in the selection of media contents, not as passive recipients, seeking to meet their societal needs (Morley 1992: 52).

In Britain, media research followed its own paths. Like the old Frankfurt School, British cultural studies scholars in the early 1970s were keenly interested in media power. They shifted, however, the analytical focus from production to reception. Influenced by Gramsci and Foucault, they held the view that media producers have no monopoly of power; this is always shared with consumers (Askew 2002: 5). Although Raymond Williams, the Cambridge don, was the founding father, Birmingham remained the centre of British cultural and media studies through the 1970s and 1980s. For many years, Stuart Hall was the leading figure of a network of scholars who kept their distance from America's media effects researchers. They had an explicitly leftist agenda: to fight capitalism, racism and patriarchy (Lull 1990). Most practitioners followed Hall in his rejection both of economic determinism and of the structuralist stress on the autonomy of media discourses, i.e., the idea of texts as the sole producers of meaning. Instead they emphasised creativity and social experience, placing media and other practices within the ‘complex expressive totality’ of a society (Curran et al. 1987: 76-77). Hall argued persuasively that although media producers shape the future ‘decoding’ of their texts by encoding what he called ‘preferred readings’, they hold no ultimate control over their audiences' interpretations (Askew 2002). Most audiences actively appropriate media contents, turning them to their own uses, but within the constraints imposed by both medium and message.

The bulk of media research down the decades has been carried out in North America and Western Europe. Media anthropologists, who are relative latecomers, have helped to extend the geographical reach of media research beyond its North Atlantic heartland. In theoretical terms, however, they remain resolutely North Atlantic, yet they are far more influenced by Williams, Hall and other British cultural studies luminaries than they are by American media effects research. These anthropological studies share a careful attention to ethn...