![]()

CHAPTER 1

Designs on/in Africa

DIPTI BHAGAT

Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title. Subtitles may include the words ‘Zanzibar’, ‘Masai’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Zambezi’, ‘Congo’, ‘Nile’, ‘Big’, ‘Sky’, ‘Shadow’, ‘Drum’, ‘Sun’ or ‘Bygone’. Also useful are words such as ‘Guerrillas’, ‘Timeless’, ‘Primordial’ and ‘Tribal’… Never have a picture of a well-adjusted African on the cover of your book … (Wainaina 2005)

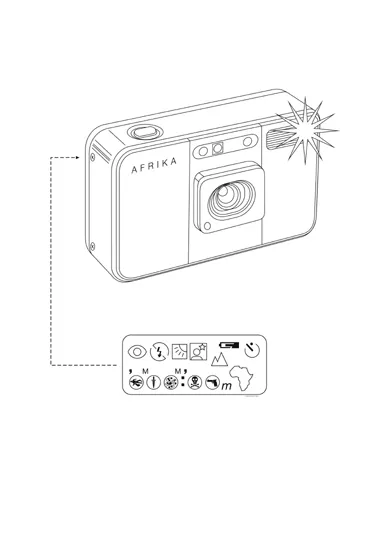

Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, writing from Norwich, England, in 2003–2004, penned a quick fire email to the editor of Granta magazine, responding to the ‘Africa’ issue. ‘Populated by every literary bogeyman that any African has ever known, a sort of “Greatest Hits of Hearts of Fuckedness”’, the Granta Africa issue stirred Wainaina’s ire. For him the Granta issue offered ‘nothing new, no insight, but lots of “reportage” … as if Africa and Africans were not part of the conversation, were not indeed living in England across the road from the Granta office. No, we were “over there”, where brave people in khaki could come and bear witness’ (Wainaina 2010). His email, a searing satire, was published by Granta in 2005. He goes on: ‘In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty … Or it is hot and steamy … Don’t get bogged down with precise descriptions. Africa is big: fifty-four countries, 900 million people who are too busy starving and dying and warring and emigrating to read your book … so keep your descriptions romantic and evocative and unparticular’ (Wainaina 2005). Fuck Afrika I an inkjet illustration (Fig. 1.1), by South African graphic designer Garth Walker (2008), pictures a similar parody: a crisp, ink outline of a compact 35mm camera with a brand name ‘AFRIKA’ in the top right, a comic book graphic star to indicate the flash and an inset diagram to reveal the icons describing the camera modes out of sight on the back of the camera. The icons in the inset for Walker’s ‘AFRIKA’ camera reiterate the stereotypical images of Africa that Wainaina lists: a full sun, an outline of the continent, a gun, a skull and cross bones, a dagger, syringe and needles, a dead body.1

Fig. 1.1 Fuck Afrika I, Garth Walker 2008, inkjet print, reproduced here by kind permission of Garth Walker. Garth Walker’s commercial work can be seen at www.misterwalker.net/ and his renowned experimental graphics publication ‘I-jusi’ at www.ijusi.com/.

The title of this chapter does include ‘Africa’; indeed it shall endure throughout. Why? Not to treat ‘Africa as if it were one country’, but because the ‘category’, or the ‘sign’ of Africa, as Wainaina and Walker drive home, persists. It looms large. As an imaginative object, the continent is, as James Ferguson puts it, more than the sum of its localities (Ferguson 2006: 4). In popular discourse and media representations, as a name, an idea and an image and also as a subject for scholarly study, ‘Africa’ remains fraught, at times burdened with alterity. It is this very sign of ‘Africa’ that intrigues; its predicament appears to be a persistent consigning of Africa to further taxonomies: of hopelessness, of urgency, of inconvenience, of silence, of perseverance. In the neo-liberal frame of the universal ‘global’, Africa is un-modern, an anomaly, ‘globalization’s antithesis’ (Bjørnsen 2008). The recent methodological shift in the humanities and social sciences to a ‘global perspective’ has meant that historians of the West have made impressive efforts to directly engage with Africa’s once ignored, now urgently implicit connections, with and across the Euroverse (Berg 2007; Desan, Hunt and Nelson 2013; Colley 2013). For design history, entangled by its Euro-American and ethnocentric historiography, the global – and Africa within that global – is an important project of inclusion and diverse representation (Teasley, Riello and Adamson 2011; Margolin 2005).

So, what is this place in the world that Africa occupies? How is the category of Africa understood as one through which a world is structured (Mudimbe 1988; Ferguson 2006; Mbembe and Nuttal 2004)? What might the relationships be between the imagined/constructed and the real – in writing and in life? For categories, arbitrary as they are, are historically constructed, impose rules and can structure how people live.2 And how might design histories engage with work which has sought to unpick predominant images of ‘Africa’? Distinctive to the field amongst other forms of history is its multi-dimensional subject matter: design. The multi-dimensionality of design is particularly illuminating if it is understood as object, process and intention, animated by tensions and ambiguities and by its histories as focused on exploring the ‘translations, transcriptions, transactions, transpositions and transformations that constitute the relationships among things, people and ideas’ (Fallan 2010: vii). These ways of thinking about the empirical work of design history suggest quite well how Africa might be written as a part of the world.

This essay is exploratory; magpie-like, I have sought what might be interesting or useful or instructive for design histories of Africa. I consider the ‘global’ in history’s current focus; some historians, Africa scholars especially, are sceptical of the flattening impetus of recent discourses of globalization, and argue in favour of retaining a focus on Africa precisely because the category of Africa is constituted through a series of practices that come under historians’ scrutiny. Through some examples of things, people and ideas in Africa, this chapter tries to write against the grain of what Africa is not.

Africa and the Limitations of Global History

Writing in what Geoff Eley calls the ‘din’ of ‘globalization talk’ (Eley 2007: 161–162), African historian Frederick Cooper questions globalization as a concept and analytical tool (Cooper 2001). He acknowledges the validity of an underlying ‘quest for understanding the interconnectedness of different parts of the world’ (Cooper 2001: 189–190), yet remains (see also Cooper 2013) dissatisfied with the word ‘global’, as too singular, boundless in its claims to universality and unfeasibly planetary in scale; and with globalization as a presentist obsession with processual teleology that seeks to explain ‘the progressive integration of different parts of the world into a singular whole’ (Cooper 2001: 211). Here, Cooper detects the traces of modernization theory of the 1950s and 1960s; yet its premise that postcolonial nations progress from traditional to modern, rural to urban, subsistence to industrial economies was discredited for its (first the West then the rest) ethnocentric tendency to propose a broad, large-scale process, seemingly ‘self-propelled’ and thus occluding historical detail and precise questions about people’s agency (Thomas 2011: 729–731; Cooper 2005: 113–117; 2001).

Cooper warns Africa scholars especially of a concept that emphasizes ‘change over time but remains ahistorical, and which seems to be about space, but which ends up glossing over the mechanisms and limitations of spatial relationships’ (Cooper 2001: 190). Rather, he argues for ‘historical depth’, ‘precision’ and particular alertness to the ‘time-depth of crossterritorial processes, for the very notion of “Africa” has itself been shaped for centuries by linkages within the continent and across oceans and deserts – by the Atlantic slave trade, by the movement of pilgrims, religious networks, and ideas associated with Islam, by cultural and economic connections across the Indian Ocean’ (Cooper 2001: 190). While he accepts that histories written as though contained in solely national or continental structures may be limited, he balks at the language of globalization that suggests the only container is planetary. David A. Bell also queries the effectiveness of placing past events in such ‘vast contexts’ (Bell 2013). Indeed, what happens to the analyses of power – and its limitations – in the flatness and abstraction of planetary scale, when the structure of Empire (for example, or ‘nation’) is replaced with universal ‘global flows’? What happens to national histories on which global histories rely? For the ‘global’ must depend on an inter-national or even local context to be made real or illustrative.

Words and definitions seem to matter. For James Ferguson, ‘The global, as seen from Africa, is not a seamless, shiny, round, and all-encompassing totality (as the word seems to imply). Nor is it a higher level of planetary unity, interconnection, and communication’. Indeed, for Ferguson, writing about Africa’s place in the current neo-liberal, world order, Africa throws into sharp focus the inadequacy of the concept-word, and emphasizes rather the asymmetry and inconsistency of globalization:

Rather, the ‘global’ we see in recent studies of Africa has sharp, jagged edges; … It is a global not of planetary communion, but of disconnection, segmentation, and segregation – not a seamless world without borders, but a patchwork of discontinuous and hierarchically ranked spaces, whose edges are carefully delimited, guarded, and enforced. (Ferguson 2006: 48–49)

Nevertheless, the ‘global turn’ in history – perhaps the striving for a ‘global approach’ or ‘global history’ collectively – has generated a huge range of studies, often opening up valuable new perspectives. Much work has been done to emphasize globalization as a historical phenomenon (Moyn and Sartori 2013; Desan, Hunt and Nelson 2013; Eley 2007), frame its chronologies (Hopkins 2006; 2002) and locate the historical roots of the concept (for a brief review, see Subrahmanyam 2007: 332). Historians and design historians have variously deployed the ‘global’ as a meta-analytical category (e.g. to emphasize interconnectedness; Adamson, Riello and Teasley 2011), as a substantive scale of historical process, for example to focus on modes of circulation of goods, or imperial transformations (Bayly 2004), or, more innovatively, to consider the intellectual history of the conception of the ‘global’ as used by people in the time and place historians study (Moyn and Sartori 2013; Colley 2013). Some avoid this highly contested term – the ‘global’ – because of its need for definition and attendant perils (see the essays in Desan, Hunt and Nelson 2013): global histories and design histories tend, like their subjects, towards complexity and contradiction. Much ‘global’ history scholarship involving detailed, in-depth research seldom offers a seamless picture of ‘planetary communion’ (Ferguson 2006: 48–49); indeed, in this work, the ‘global’ is perhaps less scalar, more a way to connect empirical detail and larger processes or structures across two or more places or regions. In which case, can the study of flows, circuits, connections and power dynamics between two or more locations contribute to our shared grasp of ‘globality’ (a condition so complex yet so singular and vast in its inscription that it is doubtful if it should be applied at all)? Are these approaches best described as ‘interconnected history’, and thus is there a more ‘differentiated vocabulary’ to enhance thinking about specific, complex connections and confines in writing design history, and African design histories in particular (Cooper 2013: 284; 2001: 213)?

Towards Histories of African Design

For scholarship on Africa, these emphases on connections and confines have the potential to unravel dominant and enduring imaginings of Africa as being apart from the world, residual, a poor reflection of something else, to highlight instead the entanglements within and ‘embeddedness in multiple elsewheres of which the continent actually speaks’ (Mbembe and Nutall 2004: 348). ‘Multiple elsewheres’ are important: for current visions of the ‘global’ tend to focus on the expansion of European ‘modernity’, which is also temporally limited and fixes Africa’s inter-continental connections and diaspora in the Western hemisphere/Atlantic Eurosphere. Lynn M. Thomas explains how Africa has been key to defining an image of the ‘modern’: as its antithesis, as a signifier of modern ills, as a sign of modern primitivism, as a site to test modernization theories, while modernity has reified the divide between precolonial, colonial and postcolonial histories (Thomas 2011: 727–733).3 The history of Africa’s long-distance connections is older, and differently sited, than its history of connections with Europe. Studies in historical archaeology have shown in nuanced detail how shifting patterns of coastal Swahili (East African) cosmopolitan culture between the tenth and sixteenth centuries grew out of alliances between local elites and foreign merchants (men, both) who negotiated trade in commodities from the southeast African interior beyond the coast (including iron, ivory, gold, timber, skins, slaves and tortoise shell) in exchange, in part, for Islamic, Chinese and later southeast Asian ceramics, key luxury imports of the Islamic Oceanic trade. Evidence of diverse consumption by elite men, women and children in Swahili societies of these imported ceramics – as tableware in public festivals, for display in intimate, honorific or ritual contexts or worn as personal ornamentations, including re-use – show the socio-cultural status of these ceramics in urban Swahili culture (see Fig. 1.2 for a fine example of Ming Dynasty Lonquan Ware discovered in Malindi, Kenya). Alongside this, the limited evidence of these objects, either in agricultural coastal settlements or the continental interior that supplied raw materials for this coastal trade, suggests that urban Swahili elites carefully guarded and delimited the distribution of such luxury products (Zhao 2013; 2012). Swahili mercantile power was clearly large scale in its connections across the Indian Ocean – or to describe this connection in its own terms, the ‘Afrasian Sea’ (Pearson 1983)4 – and evolved over a long time, but it was also complex and contingent upon its particular geography and maritime climate, and the expansion of the Islamic world.

Fig. 1.2 Stoneware bowl with a thick green celadon glaze inside and out except for its unglazed centre and base (height – 7.6 cm, diameter – 18 cm); dated circa 1400–1500, Ming Dynasty, made in Longquan, China, found in Malindi, Kenyan coast. Malindi was a key entrepôt for Afrasian trade between China, Arabia and Africa, and Chinese celadons such as this one here were widely used as tableware in this part of Africa. © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

This example of Afrasian Sea trade in ceramics is a study of historical archaeology and is thus perhaps a little provocative for a design history that classically considered its subject to be ‘modern’ and ‘industrial’, serially produced (Pevsner 1936; also Teasley, Riello and Adamson 2011: 6; Lees-Maffei and Houze 2010; Margolin 2005), and thus European and ethnocentric. That ‘design’ was, and still is at times, deployed as a signifier of Euro-industrialized economies suggests that particular forms of power might have become lodged in the very definition of design: objects from Africa not described strictly as design by industry have all too often been labelled variously as curiosities, ethnography (Shelton 2000) or art. How can we study design in ‘precolonial’, ‘colonial’ and ‘postcolonial’ Africa when confronted with the fact that this use of design emerged in part from the history of what we are trying to examine – that is, the history of the so-called ‘first’ industrial revolution which has been shown to be wedded to Europe’s colonial expansion? A careful re-reading of postcolonial scholarship will remind us of a ‘deep suspicion of metanarratives that enfold global history into the history of the modern west’ (Moyn and Sartori 2013: 18). If Europe can no longer be studied in isolation (a key imperative of the ‘global’ turn in history), as the central place from which would materialize the stimulus for action in the rest of the world, then what do we do with the European and ethnocentric uses of design? Perhaps a way beyond this apparent impasse is less about re-defining design, more about engaging with the writing of design histories beyond this time limited, industrial Euroverse. Vilem Fusser’s essay on the etymology of ‘design’ (1995: 50–53) offers...