![]()

Chapter One

THE IDEOLOGY OF ELIMINATION

American and German Eugenics, 1900-1945

Garland E. Allen

RECENT THEOLOGICAL METAPHORS of the Human Genome Project as the “Holy Grail” of modern biology and literary references to our “fate being no longer in the stars but in our genes” reveal a pervasive belief, widespread in our high tech society, that much of who we are and what we do as human beings is controlled by the genes we inherit from our parents. In the past fifteen years our understanding of the genetic and molecular basis of many clinically definable physiological traits—cystic fibrosis, the various thalassemias, lipid and carbohydrate storage diseases, chronic granulomatous disease, and more than eight hundred others—has increased exponentially. In that same time period the Human Genome Project has been put in place, amid claims that the new knowledge of our genetic “blueprint” will revolutionize our future and provide solutions to myriads of previously intractable medical and social problems. Techniques involving somatic gene therapy and germline gene replacement, or claims that genetic engineering can lead to the design of molecules that substitute for the products of defective genes, all lead to the belief that in genetics lies the answer to many of our society's woes.

Nowhere have genetic claims been more prominent, or received more sensational treatment, than in the area of human mental, personality, and social traits. Whether in the guise of sociobiology twenty years ago, human behavior genetics in the past ten years, or “evolutionary psychology” in the last five, we have all been treated to a continuing barrage of reports on research purporting to show a genetic basis for a wide variety of social behaviors. Headlines on the covers of all our national magazines have driven this point home to even the most casual reader. Everything from general personality to alcoholism, schizophrenia, manic depression, and criminality has been claimed to have a significant genetic basis. We are what we are largely because of our genetics.

Most of these behaviors are presented as pathologies that have led to the observed widespread and significant increase in a variety of social problems, from the alarming rise in crime and drive-by shootings in the last decade to alcoholism, manic depression, and an increase in substance abuse and susceptibility to stress. The implications of these claims are generally twofold:

1. Because behavioral traits are to a significant degree controlled by genes, they are fixed and cannot be altered by environmental change; they can only be managed. Hence, traditional methods of trying to solve social or psychological problems—one-on-one therapy, counseling, reduction in stress—have been shown to be ineffective, and should be replaced by a more rational and medical protocol, employing genetically based, or at least genetically “informed,” solutions, including the use of behavior-modifying drugs, which substitute for defective gene products.

2. The second implication, following directly from the first, is that while we may not have full answers yet as to how genes control behavior, and thus to how genetics can inform us about future social decisions, we should nevertheless look to Science (with a “capital S”), particularly Medical Science, rather than to social science, for answers to these large-scale social problems. Biological psychiatry is the medical offshoot of this general spread of what is called scientism, that is, a strong and generally uncritical faith in the power of science.

Thus, genetics has become, in the words of Walter Gilbert, the “Holy Grail” of modern biology and medicine. However, the quest for the Holy Grail of Christian mythology has proved remarkably elusive, and the attempts to call forth genetic explanations for personality and social behavior have not fared much better, as evidenced by a “lack of progress report” published in Scientific American in June 1993. Such claims, whatever their scientific merit, or lack thereof, align with endeavors to place the cause of social problems outside the social sphere. The term “genetic (or biological) determinism” has been applied to this “new astrology”—our fate being now, in James D. Watson's words, “in our genes” rather than “in the stars.” Despite its scientific clothing, however, there may well be more to worry about with our new biomedical Emperor than meets the eye.

Overview

I do not wish to argue that there is no genetic component to human mental and behavioral traits. I have no doubt that there is, though how significant it is compared to the input from experience over the course of our developmental lifetime is generally difficult, if not impossible, to determine. Nor am I going to argue that technologies such as gene therapy, if they are ever feasible, should be rejected because they bring us too close to “playing God.” Genes are real, and we are learning more every day about the conditions they affect and the molecular basis of their functions. Rather, I want to argue that the attempt to promote genetic determinist explanations for social problems is driven more by economic and social contexts than by the availability of new and more reliable scientific data. While all science is to some degree culturally driven, theories of human social behavior are necessarily and overtly more so than most. This need not be a bad thing at all—many culturally derived metaphors or analogies, ways of conceiving of problems or picturing hypotheses, have led to very creative scientific ideas. What does become problematic is when we ignore the fact that science is culturally situated and thereby fail to examine which cultural biases or ideas help and which impede our understanding of the phenomena—in this case, the origins of our social behavior—we are trying to explain.

There are, of course, numerous problems with making strong claims about the genetic determination of complex human traits, especially behavioral ones. These problems reside in both biology and ethics. On the biological side, geneticists years ago moved beyond the view that single genes, or even multi-gene complexes, produce a fixed and invariant phenotype, recognizing that the phenotype for many traits—most principally behavioral ones—is far more plastic than classically portrayed. Rather than invariable outcomes, genes have norms of reaction that in most cases yield a variety of phenotypes under a range of environments. That range of environments includes not only the external environment in which the organism lives, but also the genetic environment—the genetic background, as it is sometimes called—in which every gene functions. Development, the process by which genetic information is ultimately translated into phenotype, has until recently been a little-understood and much-overlooked aspect of genetics. It is just now beginning to come back into its own at the molecular level, where the focus is on how genes are turned on and off and how they interact to produce a particular outcome. That process, as we are beginning to find out, is subject to a wide range of influences, both genetic and environmental.

In addition, defining complex behaviors in any kind of rigorous way (what is an “alcoholic” or a “criminal”?), collecting matched and well-controlled data, and determining the environments to which human beings have been subjected pose staggering methodological problems.

On the ethical side, of course, even to begin to disentangle the respective roles of heredity and environment in the development of behavioral traits requires the sort of rigorous, controlled experiments on human subjects that most scientists are, thankfully, loathe to pursue. So I am not sanguine about the prospects of ever achieving a meaningful answer to questions about any significant genetic components of our behavior.

But it is not the intricate problems involved in the study designs or the statistical analyses of the data about such traits on which I wish to focus here. Rather, in the spirit of George Sarton, one of the first historians of science who recognized science as a cultural product and its very basis as a necessary expression of cultural assumptions, I would like to ask why genetic or biological determinist theories receive the attention that they do at the time in history that they do. If the history of science has any heuristic value—and I think that it does—one benefit is surely as a means of understanding the larger picture of how and why certain questions get asked and certain answers get given at any particular time and place. Moreover, once we have answered those questions, I think we can learn from the past to determine how we might respond to similar situations in the present.

Fortunately for our inquiry, history can give us some clues about where genetic theories of social behavior can lead. In the early decades of this century, in many countries, a set of biological determinist claims, similar to those we are encountering today, was promulgated with the scientific authority of the day. Known as eugenics, this organized and influential movement was prominent in most Western countries, especially in the United States, Britain, and Germany. The extensive historical analyses of eugenics now available, by authors such as Daniel J. Kevles, Diane Paul, Mark Adams, Pauline Mazumdar, Sheila Weiss, Robert Proctor, Paul Weindling, Stefan Kühl, and Nils Roll-Hanson, among others, offer a rich data set on the economic, social, and political context in which that movement developed, as well as the political and social consequences to which it led. The history of eugenics also provides some important parameters for comparison to and understanding of the genetic claims that abound today and suggests how current claims are being or might be used. Nowhere is this history more dramatic and disturbingly relevant than in the case of Nazi Germany, where genetics and its associated eugenic claims became the centerpiece of an economic and a racial ideology that ultimately led to the Holocaust and the deaths of millions of people. It was eugenic principles, both developed in Germany and borrowed from the United States, that gave the Holocaust its scientific legitimacy. We turn now to a brief examination of eugenics as it developed in the early 1900s out of a renewed interest in breeding and heredity in agriculture.

Eugenics and Its Research Program, 1900–1940

“Eugenics” was a term coined in 1883 by Francis Galton, geographer, statistician, and cousin of Charles Darwin. It referred to “the right to be well-born” or, in the words of Galton's foremost American disciple, Charles B. Davenport, the “science of human improvement by better breeding.”1 Eugenics dominated much of the social reform thinking that abounded in the first four decades of this century. Its explanations were couched in terms of the then-new and exciting field of Mendelian genetics. Eugenicists argued that many social problems could be eliminated by discouraging or preventing the reproduction of individuals deemed genetically unfit (negative eugenics), while desirable social traits could be increased by encouraging reproduction among those deemed most genetically fit (positive eugenics). Eugenicists thought of themselves as bringing the latest scientific research to bear on old and previously unsolved social problems.

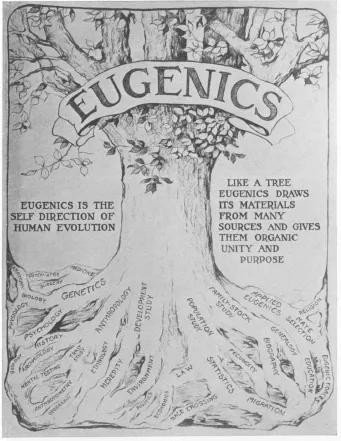

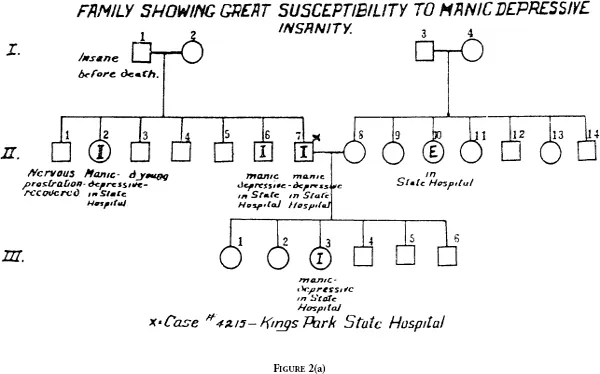

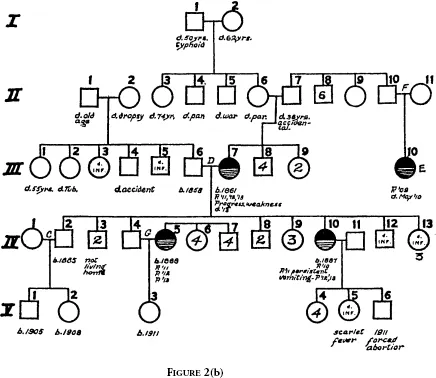

Many eugenicists, especially those carrying out research work, had a background in biology, but they saw their work as drawing on a wide variety of fields (fig. 1). Many had an interest in, or experience with, agricultural breeding and thought of their work as extending the knowledge of animal husbandry to improving the human species in much the same way as a breeder improves a flock or herd. “The most progressive revolution in history could be achieved,” Charles B. Davenport wrote in 1923 to textile magnate W. P. Draper, “if in some way or other human matings could be placed on the same high plane as…horse breeding.” Indeed, as historian of science Barbara Kimmelman has shown, the first organized eugenics group in the United States was founded in 1906 as the Eugenics Committee of the American Breeders’ Association, headed by David Starr Jordan, then president of Stanford University.2 Like the breeder, the eugenicist used pedigree analysis to determine the hereditary makeup of family lines (fig. 2); but unlike the breeder, the eugenicist could not use controlled mating experiments to test conclusions drawn from pedigree analysis. As a result, social transmission and biological transmission were often conflated. Despite this limitation, eugenicists put forth numerous claims for the inheritance of a wide variety of behaviors and conditions, from pauperism to scholastic ability, feeblemindedness, manic depression, pellagra, and thalassophilia (love of the sea). Moreover, they relied on and extended late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century lineage studies, such as those of the infamous Juke and Kallikak families, which supposedly documented in a dramatic way the ultimate outcome of hereditary degeneracy (fig. 3).

FIGURE 1: Eugenics was seen by its advocates as a multidisciplinary enterprise, drawing on fields such as genetics, statistics, psychology (including especially psychometrics, or mental testing), medicine, and anthropology, among others. In the United States and Germany, the genetic, or hereditarian, element in eugenic thinking was particularly strong. The leafy branches of the eugenic “tree” were thought to include a general level of eugenic “education” among the public, social legislation such as voluntary or involuntary sterilization laws, and political reforms such as immigration restriction. This image was the logo for the Third International Congress of Eugenics, held in New York City at the American Museum of Natural History (whose director and president, Henry Fairfield Osborn, was an avid eugenicist), 21–23 August 1932. [From A Decade of Progress in Eugenics: Scientific Papers of the Third International Congress of Eugenics, held at the American Museum of Natural History, New York (Baltimore: Williams and Wilkings, 1934), Plate I] A clearer version of this image can be obtained from the Eugenic Image Archive established by the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, at the following web site: http://vector.cshl.org/eugenics/. Image # 233.

Much of the research work was carried out by or organized through the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island. The ERO was the institutional nerve center of North American eugenics. It was directed by Charles B. Davenport and funded by the Harriman family of New York until 1916, after which it was taken over by the Carnegie Institution of Washington and maintained until its final closure in 1940.3 The ERO was managed by Davenport's enthusiastic minion Harry Hamilton Laughlin, whom he had recruited in 1910 from a teaching position at an agricultural and teacher-training school in northeastern Missouri. Laughlin served eugenics in a number of capacities: superintendent of the ERO (1910–1940), propagandist in state legislatures, “Expert Eugenics Witness” to the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in the 1920s, tireless organizer of meetings, author of newsletters and articles on eugenics, and head of a series of summer training sessions for eugenics fieldworkers, held at the ERO and funded by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. In the early years of its existence, the ERO boasted a distinguished board of scientific advisors, including such important figures as W. E. Castle (mammalian geneticist at Harvard), David Starr Jordan (who, before becoming a university president at Indiana, then Stanford, was a well-known ichthyologist), Irving Fisher (economist at Yale), Thomas Hunt Morgan (at the time, just beginning at Columbia the work with the fruit fly Drosophila that would later earn him a Nobel Prize), and Alexander Graham Bell. Besides the ERO, many other eugenics organizations existed in the U.S., including state branches of the nationwide American Eugenics Society, the Race Betterment Foundation (funded by the Kellogg cereal family in Battle Creek, Michigan), and the Human Betterment Foundation in Pasadena, California. The ERO, however, served as the major research center and clearing-house for much eugenics work done around the world.

FIGURES 2(a) and 2(b): These are two family pedigree charts of the sorts constructed by eugenicists to sho...