![]()

Chapter 1

THE ICTY INVESTIGATIONS

Interview with Jean-René Ruez

Isabelle Delpla (I.D.): Between 1995 and 2001, you led the inquiry into the July 1995 Srebrenica massacre. You have on several occasions presented the results of your investigation before the ICTY, in particular during the trial of General Krstić, commander of the Drina Corps of the Army of the Republika Srpska,1 where your testimony lasted three days.2 Could you provide a general idea of the scope, objectives, and principal findings of your investigation into these events? In particular, can you explain how the distinction between combatants and non-combatants—the foundation of international humanitarian law—was applied?

Jean-René Ruez (J.-R.R.): The inquiry began in Tuzla on 20 July 1995; in judicial terms, it was thus a flagrante delicto investigation. The ICTY investigation concerned the criminal events that followed the fall of the enclave on 11 July 1995. These introductory remarks set the limits of the criminal inquiry. The investigation therefore did not relate to the causes of the enclave’s fall and no one was charged with the “crime of seizing a UN safe area.” Nor did the investigation address air strikes or the reasons why they were not carried out.

“Krivaja 95” is the codename that was given by the Army of the Republika Srpska to the operation that aimed not to occupy the Srebrenica enclave, but rather to reduce it to the size of the town in order to make residents’ living conditions so intolerable that the UN would be forced to evacuate the area.

Against the advice of his staff officers, Ratko Mladić nevertheless decided on 10 July to capture the town. This had not been part of the initial plan. When the Army of the Republika Srpska took Srebrenica on 11 July, the population fled in two directions: women, children, the elderly, and men who did not want to abandon their families or thought they had nothing to fear from General Mladić’s forces set off toward a small industrial zone called Potočari, where the main UN base was housed in an abandoned factory. Around 25,000 refugees assembled in this area.

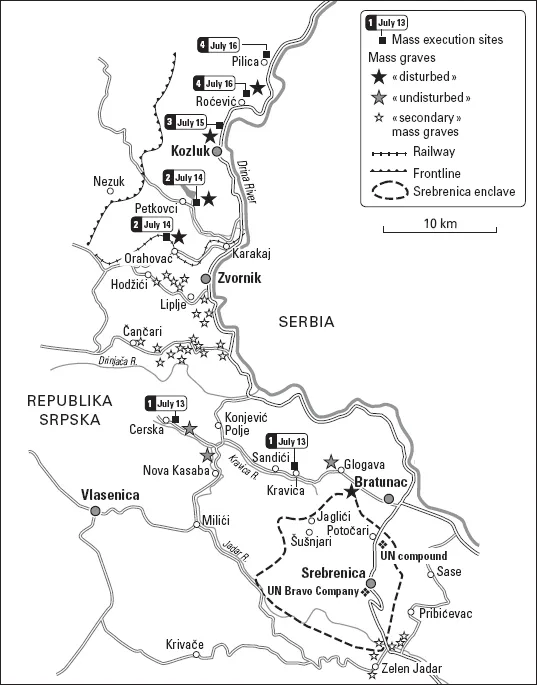

MAP 6. Srebrenica: Execution sites and mass graves

Most of the men gathered at a place called Šušnjari, in the northwest corner of the enclave, where they later decided to cross the lines, traversing minefields in single-file formation. They included the soldiers of the twenty-eighth division of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina as well as all able-bodied men who had not left for Potočari. It was not until the following day at noon that the tail end of the column finally left Šušnjari. The column was comprised of a mix of armed men and unarmed civilians. At this point, it was possible to consider every man as a “potential combatant though in civilian dress”—the previous day a general mobilization order had been issued to the entire male population of the enclave—or in any case as legitimate military targets to the degree that men were still carrying arms or were marching among soldiers.

This column reached the road intersection located at Konjević Polje. With the soldiers leading, around eight thousand crossed this sector in the evening of the 12th. I will say nothing further of the fate of this military column because it is not part of the inquiry: six thousand of them joined the Bosnian forces after breaking through the lines near Zvornik on 16 July, an episode that belongs to military history, not to the criminal record. Since we are unable to prove that they were murdered, those killed while seeking to flee the enclave must be considered as combat deaths and so are not counted among the victims who were executed while being held by the Army of the Republika Srpska.

Indeed, the ICTY inquiry, in conformity with international humanitarian law, does not judge military combat or the fate of combatants. It does, however, apply to the fate of non-combatants, whether originally soldiers or civilians; it applies, in other words, to all those who are not, or are no longer, in a position to fight.

After the head of the column passed through Konjević Polje, Serb forces closed the area, trapping the other refugees and runaways in the hills between Konjević Polje and Srebrenica (see map 6). On 13 July, this group decided to surrender to the Serb forces, enticed to do so by the fact that some Serb soldiers were wearing stolen blue helmets and claimed through megaphones that the UN and the International Red Cross were present.

At the same time, a process of forced transfer of the population that had sought refuge in Potočari began on 12 July using buses and trucks. In Potočari itself, troops created an atmosphere of terror, committing numerous murders while proceeding to separate men from women and children. Chaos reigned among the refugees. The evacuation was completed in the late afternoon of the 13th.

Widely known to the media, these events represent only the “tip of the iceberg.” Next, the men were assembled in several places. This was Phase One of the extermination operation. Among others, these assembly points included Bratunac, Sandići, the soccer stadium of Nova Kasaba, and the Kravica hangar. At Bratunac, the executions began on the 12th with clubs, axes, and throat-cutting. This was not a mass execution but rather a matter of sporadic murders. Summary executions also took place along the road between Konjević Polje and Sandići. At the road intersection of Konjević Polje, there were two assembly sites at which sporadic murders also took place. Correlations between several survivor accounts and our research shows that some men were even killed in mass graves previously dug for them, where they were subsequently buried, since we found bullets under the bodies. At Nova Kasaba, there were also sporadic executions, as well as some that were more systematic. At this stage, it is clear that, regardless of the men’s initial status, they could no longer be considered combatants. Notwithstanding Mladić’s claims that, in this area, only soldiers and runaways were killed in combat operations, many of the cadavers had their hands or arms tied behind their backs. The type of restraint used, especially in this southern zone, is a flexible metal band that is highly practical for tying someone up from behind and impossible to slip out of once attached. A group of at least five hundred individuals were taken into the Kravica hangar and executed using automatic weapons and offensive grenades. The crime scene technicians who minutely examined the site found blood, skin, and other human tissue as well as explosive residue on the walls. One hundred and fifty prisoners, their hands tied behind their backs and some with bound feet, were transported in three buses to the Cerska valley. All of them were shot along the roadside and their bodies covered by an excavator. Still other prisoners were transported to the Jadar River, where they were executed by being shot from behind.

Thus, by 13 July, numerous executions had begun taking place, but the process was still disorganized, even anarchical. In reality, you could sum things up by saying that anyone who wanted to pull a trigger that day had license to kill. The same day, Serb army leaders, realizing that not all of the prisoners could be executed in this way, decided to begin by assembling the prisoners in Bratunac. While this was being done, officers of the security branch of the Drina Corps moved more than thirty kilometers northward to the Zvornik zone to scout out detention and burial sites, which were in fact to serve as execution sites. The transfer of the prisoners was thus planned to begin on the night of the 13th to the 14th. No provision for food or drink was made for the prisoners. Records of security officer movements were found during searches of the headquarters of the Bratunac and Zvornik brigades, their drivers having failed to destroy these records. It is the drivers’ log-books that enabled us to confirm that we had in fact found all of the crime scenes, since these sites matched those listed in the drivers’s handwritten records. For lack of transportation, those who could not be relocated on the day of the 13th were executed on the spot.

Phase Two of the extermination operation began during the night of the 13th to the 14th July, when a first convoy headed north from Bratunac to Zvornik. The prisoners were informed that they were being transferred as part of an exchange and taken to schools in Grbavci and Petkovci. Those held at the Grbavci school were blindfolded and executed in nearby Orahovac. After a number of them were tortured, those held at the Petkovci school were executed at the bottom of a nearby dam. In Orahovac, the wounded and dead were gradually buried, some while still alive, by excavators and backhoes. At the Grbavci school, we found a large number of blindfolds at the surface. In the trenches, numerous cadavers also had blindfolds that, when compared to those found at the surface, enabled us to link the execution site with the burial site. At the dam, near Petkovci, we found spent cartridge cases and a very large number of cranial fragments, evidence that the killers often shot their victims in the head.

The evacuation of Bratunac continued into the night of the 14th to the 15th. Approximately 500 prisoners were transferred to the Roćević school, north of Zvornik. On the 15th, they were all executed not far away, near Kozluk. The same day, the prisoners remaining in Bratunac were taken to two public buildings in Pilica, the school and the cultural center. The approximately 1,200 prisoners held at the school were executed on the 16th at the Branjevo military farm and 500 more from the Pilica cultural center were executed that same afternoon. We later found the same type of residue in the cultural center as that found in the Kravica hangar.

The chronology of the “clean-up” operation on the ground—i.e., the burial of bodies—proceeded from the south northward. If you consider all of the crime scenes, they fall into a northern zone and a southern zone, where the executions were less organized, if equally systematic. In both cases, all of crime scenes were within the area assigned to the Drina Corps.

Next came Phase Three of the operation. During the Dayton negotiations in the Fall of 1995, it became clear to the Republika Srpska authorities that there would be inquiries into these events. The Drina Corps then launched an effort to camouflage evidence of their crimes that was logistically as great as the extermination operation itself. They cleverly—and even maliciously—left a small number of cadavers in the primary mass graves so that, if we found them, we would conclude that there had indeed been murders and that witnesses had thus probably told us the truth even if, instead of numbering in the hundreds or thousands, the victims numbered in the tens and twenties.

Nearly all of the primary mass graves were dug up in 1996 thanks to the efforts of Professor Bill Haglund who, as chief of the ICTY exhumation team, spearheaded this critical operation.3 A fair number of the cadavers were found with their hands tied behind their backs, and one victim had an artificial leg and vertebrae that were so fused together that he would not have been able to stand erect. The very fact that these individuals were executed obviously contradicts claims that the victims were combatants. At this point, we faced a serious problem, however: How could we be sure whether the bodies that we had located represented 10 percent or 90 percent of the total number of victims, since at each site eye-witnesses referred to hundreds of victims killed?

During this third phase of the Drina Corps’s operation, primary mass graves were reopened with excavating equipment and the cadavers were transported in trucks toward more remote locations and dumped into twenty-six secondary gravesites spread throughout the zone controlled by the Drina Corps. All of these trenches were dug along similar lines, and they were obviously excavated by engineering units, since each is of the precise depth of a combat tank buried so that only its turret protrudes. Anywhere between one and four truckloads of bodies were dumped into each trench. Analysis of the objects found at these locations, such as cartridge cases, blindfolds, ligatures, and fragments of broken glass, along with examination of the soils and pollens, offer a cluster of clues that allow us to link the mass graves that we called primary to those that we termed secondary.

The teams of experts we sent to carry out the exhumations were multinational and made up of highly qualified archeologists. Their responsibilities ranged from preserving each body part and object that they uncovered to examining the excavator tracks in the trench bottoms, which allowed us to identify anomalies in the treads of individual machines.

With the exception of a handful of sites, the southern zone was also part of this effort to conceal evidence. One such exception was a site in the Cerska valley that went untouched. There are three possible reasons for this. The first is that the site contained only 150 bodies and that the officers deemed this too insignificant a number to be worth the trouble of reopening the trench. The second hypothesis is that because of a lack of organization during the day of 13 July, the security officers may well have been unaware of this particular execution site. The third hypothesis is that the site is so remote that they thought it would not be found. Indeed, we did not locate it using aerial imagery4 but by cross-referencing witnesses’ testimony.

Simply presenting these facts before the Tribunal, documented by maps and photographs, took up three days. For each visual document, one could present a large number of additional photographs to better explain all of the details of these crime scenes. In addition, there were reports from expert witnesses, including crime scene technicians and exhumation reports. The military analysis constitutes a whole separate body of evidence concerning the situation. I should add to that the analyses of all of the transcribed radio interceptions at our disposal. It is the whole array of these nested “Russian dolls,” one fitting into the other, that gives an overall picture of the situation. As the indictments show, there were many crime scenes, especially when one considers that, during the investigation, we only examined situations in which a “large number” of victims had been assassinated. Let us just say that there was a period of several years where we would not have even traveled to a site with fewer than a hundred bodies, due to a lack of time and resources.

I.D.: The difficulty that an outsider may have in understanding the nature of such investigation, which is essentially a criminal one, is due to the distance separating it from more familiar models in such contexts—that of historical investigations drawing on the archives of the Nuremberg trials, for example, or NGO investigations. Your presentation clarifies this difference, if only through the investigative powers conferred upon you. The inquiry reveals a state crime that used the apparatus of the state (the army) and public tools and buildings (schools and so forth). It seems that, for investigating into this state crime, your inquiry also draws upon the resources of the state. Here, I am referring to your use of aerial photographs and the transcripts of intercepted radio communications prepared by the Army of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This might lead one to revise one’s vision of international criminal justice as an expression of an international civil society that is independent of states.

In order to clarify the nature of this inquiry and the kinds of evidence it yielded, could you be more specific about what place you occupied as a police chief relative to the teams of specialists and experts who participated?

J.-R.R.: I need to make it clear that I cannot take a personal position on this matter because it relates to an ongoing judicial process.

Given the sheer scale of the drama, the situation was new. Nobody before us had had to soil their hands with this kind of work. The role of a police chief is that of coordinator. He is not supposed to be a one-man band who plays all of the instruments himself. He has to use what he knows in order to surround himself with people who can bring their own expertise to bear and thereby cover the many facets of such a situation. We are engaged in a judicial inquiry whose goal is to produce trials before an international court. Some trials have already taken place, and others are in progress or will be in the future. The role of the leader of the investigating team is therefore to try to understand what happened, to give a direction to the inquiry, and subsequently to assemble experts who will contribute to efforts to find out the truth. And finally, once we think we have reached a reasonable stage in that search and thus are in a position to bring charges, we have to supply technical evidence in support of them.

I.D.: What kinds of organization and skills does such an investigation require?

J.-R.R.: Whether the head of a group leads two people or ten people, his role does not change. However, if he lacks sufficient resources or manpower, he will end up having to act as a one-man band instead ...