![]()

Chapter 1

Glancing over Newspapers

Ultimatum and Suicide

Historians generally assume that the Portuguese twentieth-century in fact begins with the episode of the 1890 British Ultimatum. On 11 January, Lord Salisbury, the British prime minister, sent a memorandum to Lisbon urging the withdrawal of Portuguese troops under the command of Major Serpa Pinto, then stationed in territories claimed by the British Empire (in what is now Zimbabwe). The note in itself was rather laconic. It demanded clear instructions be sent by the Portuguese government to the governor of Mozambique to ensure Serpa Pinto’s evacuation of the disputed regions, in the absence of which the British ambassador in Lisbon would receive orders to leave the city. In nineteenth-century diplomatic language, however, this brevity was clear enough: it meant a military ultimatum.1

The event would later become the synecdoche of a national crisis largely transcending the diplomatic episode. Its historical meaning now stands not only for a deeply felt political crisis, but also the country’s late nineteenth-century financial collapse and a major break in its cultural and intellectual self-consciousness. All together, the various dimensions of the event, or the different events now combined in the crisis of the Ultimatum, gave way to an acute awareness of Portugal’s vulnerability as a historic empire – a central feature in the country’s national narrative – and its subordinate role in European history. Internally, this was the moment when both republicanism and nationalism established themselves as the two dominant political cultures of the following decades. Despite the discrepancy between the historical significance and the sobriety of the diplomatic note, the event was immediately experienced as having both deep and wide-ranging consequences. Demonstrations of all kinds followed and something decisive happened to the sense of national identity. What would become the republican national anthem, ‘A Portuguesa’, was composed at the time as an anti-British protest. Patriotism was displayed with an intensity that came close to the consistency of twentieth-century nationalism. In other words, perhaps the diplomatic note was less discreet than we were initially led to believe. Its impact, however, was not due to the indiscretion of the politicians and diplomats concerned but to the media, through whom the note emerged into intense public visibility.

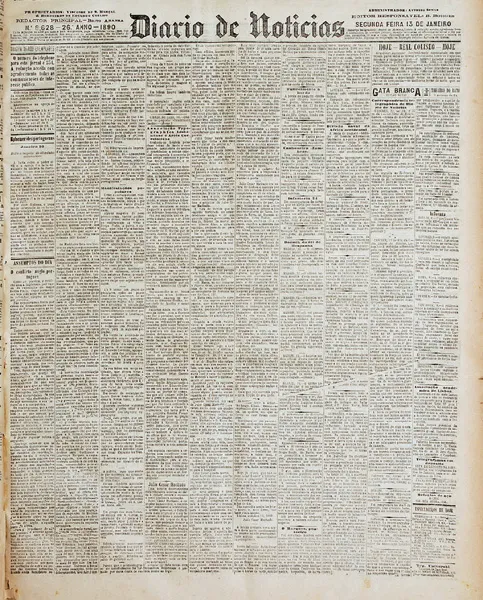

The regime of this visibility is, in itself, our problem. By looking at the reaction of Diário de Notícias – Portugal’s leading newspaper in 1890 – to the event on its front page on 13 January (Figure 1.1), we can see that such visibility was not based on images. There were no pictures or headlines about the Ultimatum, just a heavy block of text. At first sight, then, the newspaper did not keep pace with the importance of the historic event. But this impression may be biased. After more than a century of visual information, we may tend to identify journalistic sensationalism with images, whereas the report about the Ultimatum, occupying more than three columns of the paper’s front page, was entirely textual. Apparently, then, the event’s visibility must be read through the ways in which this written narrative is organized – as if what is being shown can be seen in the words.2 Only then will we be able to unveil what really happened between London, Lisbon and the African regions over which the two governments were in dispute.

Figure 1.1: Front page of Diário de Notícias, 13 January 1890. Archive of Diário de Notícias.

The article’s discreet heading, ‘The Anglo–Portuguese Conflict’, did not promise much drama. Moreover, the text started with an almost casual ‘as anticipated’, later reinforced, at the beginning of the second paragraph, with a reassuring ‘as everyone knows, or at least can imagine’.3 The outcome of the diplomatic tension between the two countries was what, according to the newspaper, could easily be ‘anticipated’ by the reader, who was also supposed to ‘know’, or at least ‘imagine’, the brutality of Britain’s display of power. It thus seemed that while the events were taking place, as they should, between ministerial cabinets and diplomatic chancelleries, part of the information was on the loose, circulating in the form of ‘serious rumours’ and leaving the newspaper with the pacifying – although secondary – role of confirming what ‘the readers already know’.

In these circumstances, one could ask: what was the use of journalism? Why should anyone buy, and read, a newspaper with information easy to anticipate, and an account of events that everyone already knew or at least could easily imagine? The answer to this question must be able to clarify the true object in the report of Diário de Notícias, or better still, the ways the newspaper transformed the information at its disposal into a narrative. On that particular Monday, the reader could not only recreate the entire exchange of telegrams between the two governments but also reconstruct the whole process through which Lisbon’s newspapers in general (the piece includes excerpts taken from Novidades and Diário Popular) organized the public perception of what was going on.

The event had started more than a week earlier, on Sunday 5 January, with the arrival of the first note sent by the British government, to which Lisbon replied on Wednesday 8 January. Taking into account the time it took, in 1890, for communications to be transmitted between the two countries, a second note from London could not have been received in Lisbon before Saturday 11 January. The anxiety was evident in newspaper reports. That day’s issue of Diário Popular (quoted by Diário de Notícias) seemed to believe that, ‘considering the language used by British newspapers, the Court of Saint James [is] expected to take [the reply sent by the Portuguese government] as an appropriate basis for peaceful negotiations’. However, according to the edition of 12 January of Novidades (once again quoted by Diário de Notícias), not only was the reply that had arrived on 11 January remarkably violent, but this had been anticipated the previous day by a first verbal demand for Serpa Pinto’s withdrawal, which did not even take into account the Portuguese reply on 8 January.

In short, what seemed to count as journalistic information was less the content of the diplomatic exchange than the form of its circulation. The event was somehow transformed in the production of information about it, and everything happened as if the news were reporting what had already been constituted as news. This may look like an impoverishment of the political event, as if there were nothing but its text, a metanarrative with no material dimension. But things were not that simple. For that same political event itself – that is, a political crisis between two governments – had been initially triggered by a network of information – a flow of discourses – circulating between London, Lisbon and several other interconnected positions in Europe and Africa:

Yesterday the government received a telegraphic warning from the governor-general of Cape Verde, informing them that an English battleship with secret instructions had arrived in S. Vicente. The possibility of an attack was creating anxiety. Zanzibar’s consul notifies that the English fleet that had concentrated there with ten ships, left towards the south, supposedly heading to Quelimane or Lourenço Marques … Finally, the [Portuguese] government knew, from information received from our consul in Gibraltar, that a fleet formed by the battleships Northumberland, Anson, Monarch, Iron Duke, was concentrated at the canal … being meanwhile reinforced by two battleships from the Mediterranean fleet, the Colossus and the Benbow, recognised as the most powerful of the British fleet.4

The newspaper thus took part in this intense network, where the constant communication between distant places produced political events that became news, which further transformed into new events.5 The last section of the report described the impact the news had had on the streets of Lisbon: ‘this and other news, discussed with more or less passion, gave rise to several demonstrations in different areas of the city’.6 In fact, Sunday 12 January was tense. Several groups of people walked the streets cheering Serpa Pinto and shouting slogans against England – ‘which’, the reporter added, ‘we will not reproduce, as it could make matters even worse in the present situation’.7 The British consulate and the Portuguese Foreign Office were stoned and several windows were broken, theatres were invaded and orchestras forced to play patriotic anthems. The crowds invariably ended up gathering in front of newspaper offices, as if the press was the last reliable institution. These people had responded to the news, and their response was bound to become news.

The reader thus had good reasons to buy the newspaper on Monday 13 January, after all. They might have known the diplomatic memorandum’s content beforehand and even imagined its political consequences, but the newspaper gave more. Namely, a narrative where that particular piece of information was organized in a continuous chain of events, as both the consequence of previous information and the cause of subsequent events. Our reader – especially if from Lisbon – might even read about episodes in which he had himself participated (the reader’s gender must be specified when readership concerns the street, for, if a given newspaper’s readership was constituted by men and women, only the former were expected to participate in public demonstrations). In that case, to read the newspaper widened the scope of participation by making readers aware of the circulating network they were part of.8

This also meant that the reader of Diário de Notícias on 13 January 1890 was able to make her own narrative by adding that day’s information to what she already knew after reading the issue of the previous day, and resuming it with the news published on the next. These considerations seem to assume that the same readers bought the newspaper every day, which is of course something we cannot be entirely sure of. More likely, that same reader did not stop reading her paper after the story of the Ultimatum but kept browsing for more information in the following columns. After all, there was still more than two thirds of the newspaper left to read. If we follow this imaginary reader as she moved forward, we can almost imagine her disbelief on discovering that the news of the British Ultimatum was not even the most dramatic piece of information that issue of Diário de Notícias had in store for her. For the day when the streets of Lisbon erupted in protest against the British, the city also witnessed the suicide of the popular writer Júlio César Machado and his wife.

Machado was none other than one of the newspaper’s main feuilletonists, writers who contributed fictional or critical texts to the feuilletons, a special section of the newspaper separate from that which contained the news. Machado had been a regular presence in the same pages that now announced his death, which made the news even more tragic, both from the perspective of the reporter – a colleague – and the reader – someone certainly familiar with Machado’s writings. His career as a feuilletonist was inseparable from the evolution of feuilletons in Portuguese newspapers: the popularity of both – feuilletons as a literary genre and César Machado as author – grew hand in hand from the 1850s (De Marchis 2009). Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, readers became increasingly used to reading these special sections where fiction and opinion went loosely together without the journalistic constraints of the news proper. This combination of different styles within feuilletons constituted a site of intense creativity where the relations between fictional and journalistic discourses opened new ways of representing reality: by the end of the century, feuilletons were closely entangled with literary realism.

In this sense, the genre occupied a unique space where the authority and legitimacy of journalism as a transparent discourse between reality and its readers had to negotiate with the more nuanced relation with the world proper to literature. Júlio César Machado was thus at the centre of a literary system where newspapers functioned as mediators in the permanent negotiation between fiction and reality. Feuilletons often showed a sharp awareness of their own concrete situation – narratives regularly published side by side with quotidian information – and reflected upon it. The young bohemians of A vida em Lisboa (Life in Lisbon), one of Machado’s first and most popular dramas, showed how ambivalent this negotiation could be. If, on the one hand, they complained about the dullness of everyday life in the Portuguese capital – on the grounds that ‘life in Lisbon wouldn’t even yield a feuilleton’ (Machado and Hogan 1861: 2) – on the other, however, they seemed to accuse that same reality of being too dramatic because of its close resemblance with the content of dramas: ‘My dear friend, usually it is not the theatre that depicts society: it is society that copies the characters in plays!’ (Machado and Hogan 1861: 38). Any contradiction between these representations of the relation between fiction and reality is only an appearance, for they ultimately showed how deeply both types of narrative were related. Lisbon’s life might lack what it took to make good drama or have too much of it. In any case, reality seemed unthinkable without its fictional counterpart as much as – if not more – fiction seemed unthinkable without its referent.

The trope of modern reality imitating popular literature has been identified as one of the most recognizable stereotypes in feuilletons (Thiesse 1984). More than a literary trope, however, this insistent image may be read as a kind of realistic common sense. For, as we have seen with the discursive origins of the Ultimatum, realism in 1890 had to focus on a reality already organized by the circulation of information. The challenge was thus twofold. On the one hand, the distinction between events and news became harder to maintain with the proliferation and interpenetration of events based on discourses and discourses that constituted events in their own right. On the other, fiction and reality were constantly blurred by the coexistence of literary and journalistic narratives within the same newspaper pages.

The most shocking thing about César Machado’s suicide was the way in which in its crudity it resembled a scene from a realist novel. Contrary to the British Ultimatum’s journalistic narrative, everything in this second event was unexpected and occurred away from public visibility. The reporter of Diário de Notícias himself had trouble getting hold of it. After all, the ‘painful news took the whole city by surprise’,9 and he was as shocked as his readers. When the ‘bad news spread’ (‘with amazing speed’), he was in no privileged position and had to run to César Machado’s house like everyone else did ‘as soon as we knew about this sad and painful news’. ‘Bad’, ‘sad’ and ‘painful news’: the reporter’s troubles were more than just the obstacles standing between him and the information. The death of Júlio César Machado had a personal, intimate, dimension that made it much more difficult to endure, and thus to narrate, than the Ultimatum itself. Half way through the report, however, the reporter suddenly seemed to gain the upper hand. The same emotional reservations initially blocking the narrative became a sign that, unlike everyone else except the police, he had been able to enter the house and see what happened with his own eyes: ‘It is hard to describe. We do so with a heavy heart and tears in our eyes’. The scene was tragic enough, but the reporter does not hesitate adding a little creativity: ‘it was obviously there that the last episode of this frightening drama occurred … [T]here is not a shadow of a doubt that the deranged spirits of our unfortunate friend and his wife had been occupied by the idea and willingness to commit suicide for some time’.10

At this point, the observed facts and the reporter’s presuppositions become hard to distinguish. It seemed that the writer and his wife were unable to cope with the recent death of their only son, thus deciding to take their own lives as well. But neither husband nor wife left any explanation. The whole report thus becomes an assumption based on the few elements that remained visible. In this sense, whereas the Ultimatum was recreated through the assemblage and articulation of public communications, the narrative of the suicide involved what happened in the invisible realm of private life, being somehow brought to public visibility. What the reporter could see – the traces left behind – matched what the police (the only other people allowed on the scene) used as clues to...