![]()

SAHRAWI SECTION

![]()

1

Identity With/out Territory: Sahrawi Refugee Youth in Transnational Space

Dawn Chatty, Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh and Gina Crivello

Introduction

Thirty years after the first wave of refugees from Western Sahara fled their territory and took refuge along the border areas of south-western Algeria, a second generation has grown up without territory, patently committed to supporting its government-in-exile's goal of return.2 Sahrawi refugee youth are highly politicized and imbued with a sense of the importance of education, which they perceive as a major weapon in their nation's fight for economic and political survival. Educational opportunity also instils Sahrawi youth with a sense of hope for a better future. They accept the transnational reality of their education and recognize that the limited resources within their refugee camps mean that they must leave their families and kin from an early age in the pursuit of education. This mobility and networking across vast distances and often several nation states is a common feature of life for these youth. Although the four (or five, if we count the smaller 27th February Camp) Sahrawi refugee camps near the Algerian border town of Tindouf are the physical locus of their lives, most Sahrawi youth recognize that they must travel for education as well as for the support networks their movements create. Whether it is summer camps in Spain or Italy, or high school and university training in Algeria, Spain, Libya, Cuba, Syria and, more recently Mexico, Venezuela or even Qatar, these placements are regarded as a ‘national’ duty to support their government-in-exile and eventually also their families. Their homes are cast widely, wherever their extended families are found, be they in Mauritania, Algeria, Spain, in the Western Sahara itself, or elsewhere. But the message remains the same: they are refugees from a territory currently occupied by Morocco. The transnational spaces which make up the core of Sahrawi young people's lives remain organized around the theme of education for the betterment of the nation as well as the more immediate needs of their family and kin.

This chapter examines the social and political conditions which have led to the emergence of significant transnational education and networking phenomena primarily among Sahrawi children and youth. Based upon family group interviews in the Sahrawi camps and individual interviews with youth in a summer host programme in Spain, the chapter examines how Sahrawi youth identities in a transnational context have emerged and how the policy of the government-in-exile has promoted and encouraged this development. The chapter then examines how Sahrawi youth come to terms with their reintegration into the refugee camps after months, and often years, abroad. We suggest that the original tribal ideology of pastoral-based mobility (Chatty 1996: 129–35; Zutt 1994: 7–9, 33–35), whilst not representative of all Sahrawi people, may help us to understand the relative ease with which many Sahrawi adults, if not the youth themselves, accept and tolerate long physical and temporal absences of close kin as part of the duty of a good Sahrawi citizen.3 The tradition of movement and dispersal among and outside the kin group – particularly by male youth – in the nomadic pastoral camps, the urban centres of the past, and in the settled refugee camps today is a cultural continuity which needs to be taken into account (Claudot-Hawad 2005). Furthermore, the almost complete material dependence of the Sahrawi state based in the refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria – although not always fully understood by Sahrawi youth – has meant that creating transnational educational opportunities for the young is a major state, as well as individual, survival strategy. Upon their return, these transnationalized youths face numerous difficulties, including those of a broadly cultural nature: how to acclimatize to the physical and intellectual emptiness of their desert refugee base after years spent abroad, sometimes in situations of relative deprivation and at other times in a richness of social experience and knowledge. The adjustment is hard, sometimes traumatic, and only just hinted upon in the data.

This chapter will open with a brief overview of the regional and global politics which superseded the flight of the Sahrawi from their home towns and desert camps to the Algerian border area of Tindouf. It will then describe the Sahrawi refugee camps themselves on the desert edge of the town of Tindouf, followed by a review of the main characteristics of the Sahrawi refugee community as they emerge from the project household interviews. Finally, we turn our attention to Sahrawi youth themselves and discuss the significance which transnational education has had on the formation of both their social and political identities, and how their reintegration has shaped that process.

Contested History

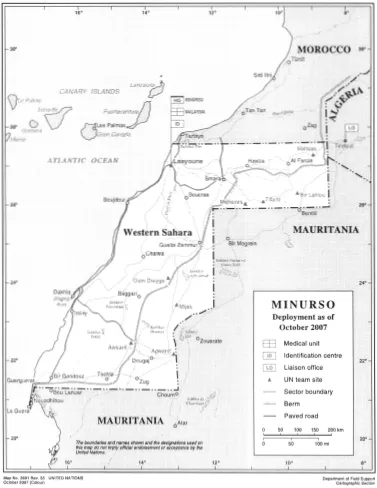

Figure 1.1: Map of Western Sahara.

Reproduced with the permission of the UN Cartographic Section.

The Western Sahara, Africa's last non-self-governing territory according to the United Nations (UN),4 became a Spanish colony in 1884. While the Spanish presence in the territory remained minimal until the mid-twentieth century, by 1936 Spain and France had formed an alliance to establish Spanish hegemony in the Western Sahara. In 1920, 253 Spaniards were present in Villa Cisneros, the main ‘urban’ centre in the territory (Yara 2003), but the discovery of phosphates in 1947 led to a massive shift in Spanish interest in the territory, which was paralleled by a mass influx of Spanish civilians and soldiers. The total Spanish civilian population reached 1,220 by 1950, more than quadrupling by 1960 to 5,304 (Damis 1983), and multiplying again almost fourfold to reach 20,126 in 1974 (Barbier 1982). Spain's desire to exploit the territory's natural resources, in addition to the need to keep emerging Sahrawi anti-colonial movements under control, led to the military presence soaring from only 700 Spanish troops in 1925 to some 15,000 Spanish soldiers by 1970 (Damis 1983).

This ever-expanding number of Spanish civilians and soldiers in the territory was accompanied by the settlement of large numbers of nomadic pastoral Sahrawi people, who increasingly moved to live around the territory's growing urban centres: Aaiun, Villa Cisneros (now known as Dakhla) and Smara. This process of sedentarization of the region's nomadic peoples occurred both as a result of the several severe periods of drought in the territory between 1949 and 1974, and also following the Spanish administration's pressure to ‘civilise’ the population.5 By 1974, between 55 per cent and 72 per cent of the Sahrawi people still based in the territory, estimated to number around 73,500 according to that year's Spanish census,6 were living in or around the main urban centres, although not all of these had given up nomadic pastoralism entirely.

Throughout the colonial period, animosity and tension towards the Spanish administration cumulatively intensified, with the first major urban-based anti-colonial movement emerging in 1968. Four years before this major organized resistance started, the UN first asked Spain to decolonize the Spanish Sahara, a request which was reiterated in December 1965, and on a systematic basis from then onwards. The UN and the Organisation of African Unity (now the African Union) stressed, as they continue to do today, that a referendum for self-determination should be held, in order for the inhabitants to decide their future. In 1973, a group of Sahrawi students, many of whom had studied in Morocco and Spain, formed the Polisario (Frente Popular para la Liberación de Saguia El-Hamra y Rio de Oro), the armed forces of the Sahrawi liberation struggle. The Polisario demanded independence from Spain, and rejected any claims made by Morocco and Mauritania to the territory. In 1975, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) published its advisory opinion maintaining the right of the Sahrawi people to self-determination. On the same day, the Moroccan king, Hassan II, announced his intention to ‘reclaim’ the Sahara through a civilian ‘Green March’ (Damis 1983; Chopra 1999). Six days after the Moroccan armed forces crossed into the former Spanish Sahara, an estimated 350,000 Moroccan civilians followed (Saxena 1995; Pazzanita and Hodges 1994). Mauritanian forces invaded from the south. Makeshift camps sprung up to temporarily shelter those who fled their homes, but these were bombed soon after in a series of raids by the Moroccan air force. Young men generally stayed behind or eventually returned to fight, while their families sought refuge in Algeria where they remain to this day.

Sahrawi Society in ‘Exile’

Contemporary Sahrawi society is widely dispersed throughout northwestern Africa. The numbers of people in ‘exile’, that is, not living in the Western Sahara, are not precisely known, but are distributed primarily in Algeria, Mauritania and Spain.

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) statistical yearbooks of 2002, 2003 and 2004, the Sahrawi refugee population of concern to UNHCR in Algeria was distributed as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Sahrawi Population of Concern to UNHCR by Camp.

| Location | Population of concern to UNHCR at location |

| |

| Smara Camp | 41,850 |

| Dakhla Camp | 40,440 |

| Aaiun Camp | 38,740 |

| Auserd Camp | 34,410 |

| Tindouf (City) | 9,570 |

| Total | 165,010 |

This is a total of 165,010 Sahrawi refugees in the camps around Tindouf, although the estimate is limited in several respects. Firstly, the UNHCR has not been able to complete a reliable census, so these figures must, indeed, be seen as merely an estimate. Secondly, the total figure is limited by an absence of information regarding the number of refugees living in the 27th February Camp. Furthermore, as the figure remains the same from 2002 to 2004, it clearly does not account for population growth.

Mauritania also hosts some 26,400 Western Saharan refugees whose situations are monitored by the UNHCR but who do not directly receive assistance from the UN body.7 This would suggest that the total population of Sahrawi refugees spread out over a number of nation states is between 190,000 and 200,000 refugees.8

The Sahrawi Refugee Camps

The emergence of the Sahrawi refugee camps took place at a time when young and adult men were at the military front, meaning that female-centred extended families played a central role in social life from the mid-1970s until the mid-1990s.9 While fathers and husbands would return to the camps on short visits during these first two decades, most men were absent from the camps on a daily basis, leading to women being in charge not only of their families, but also of camp structures as a whole. Given women's centrality in daily social and political life in the camps, Sahrawi children have been cared for by a broad selection of individuals in social and institutional settings. In addition to being looked after by older sisters, aunts and grandmothers in their respective khaimas (tents/households), the creation of crèches for young children whose mothers work outside of their khaimas has been an integral part of the social structures developed in the refugee camps.

Sahrawi women's contemporary centrality, both within the khaima and at all levels of camp life, reflects a syncretic response to the demands and opportunities of exile.10 Similarly, the diffuse familiar and institutional forms of childcare currently offered in the refugee camps represent the adaptation of some elements of social structures which characterized Sahrawi life before the occupation of the Western Sahara.

An estimated 150,000 and 200,000 refugees from the Western Sahara currently live in one of the five remotely located refugee camps set up in the desert thirty kilometres from the south-western-most Algerian town of Tindouf. Some had been nomadic pastoralists; others had fled from larger urban centres such as Aaiun, Dakhla, La Guera and Smara. UNHCR provided them tents to which some families have added on sand-brick buildings. Trucks bring water to the camps, as well as food, medicine and other basic supplies. Camp residents are almost entirely dependent on externally-provided humanitarian supplies, although food-aid is supplemented by a small amount of vegetables (mainly potatoes, onions and carrots) grown in gardens in the camps, some eggs produced in one of three (air-conditioned) hen-houses (E.U. 2004), and the milk and meat from goats and camels kept by individual families.11

Sahrawi refugees live in camps set up, with Algerian permission, in 1975 by the Polisario Front and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), an entity whose existence was proclaimed by the Secretary General of the Polisario Front (El Ouali) on 27 February 1976, the day that Spain officially withdrew from the territory. Initial assistance was offered by the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC), who, forty-eight hours after receiving a call from the Sahrawi Red Cross, sent a plane from Sweden carrying tents and medical items (Wirth and Balaguer 1976). Other NGOs and IGOs, including the International Federation for Human Rights and UNHCR,12 sent missions to the camps to evaluate the requirements of medical and humanitarian assistance, and documented the abuses which had taken place during the invasion. Between 1975 and the mid-1990s, humanitarian aid and projects in the camps were managed by the refugee community itself, with only a minimal presence of international NGO/IGO workers in the camps.13

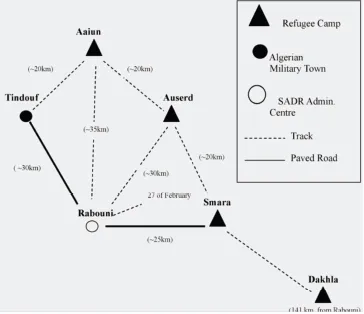

There are four major camps, one small camp (27th February Camp, also known as ‘The Women's Camp’), and one administrative centre (Rabouni). The camps are named after the four major urban centres in Western Sahara: Aaiun, Smara, Dakhla and Auserd. These camps, called wilaya (pl. wilayat, provinces), are located approximately twenty-five to a hundred kilometres from the Algerian military border town of Tindouf. Most of the camps can be reached in half an hour to an hour's driving time from Tindouf, although Dakhla is considerably further away to the south, located closer to the Mauritanian border. Each camp is intended to function as a self-contained wilaya of the SADR. Each wilaya is divided into six dawa'ir (sing, daira) or districts, with Dakhla claiming seven due its slightly higher population. Each daira is subdivided into four ahya'a (sing. hay) or sub-districts.

Figure 1.2: Map of Sahrawi Camps near Tindouf (South-West Algeria). Adapted from Train in Caratini (2003).

Thirty years following the war which prompted the Sahrawis to flee to Algeria, the refugees have become a highly organized community and participate in institutions ranging from local committees that run and manage small neighbourhoods, to larger organizations that include the National Union for Sahrawi Women (NUSW) and the Union for Sahrawi Youth (UJSARIO). Consequently, the individual refugee's daily life and activities intersect to a large degree with programmes and projects funded and run by international humanitarian organizations, the camp-based state, with its various governmental departments and community organizations, and the family. Moreover, the government, especially through the Ministry of Cooperation, ensures that external interventions, regardless of their nature and objectives, are screened and examined, a process that is bureaucratic in structure and chara...