![]()

Chapter 1

BIOCULTURALISM

Stanley J. Ulijaszek

Introduction

It is symptomatic of the new anthropological holism that terms, such as bioculturalism, are created to signal the attempt to reconcile divergent sub-disciplines. In biological anthropology, biocultural approaches are those that explicitly recognize the dynamic interactions between humans as biological beings and the social, cultural and physical environments they inhabit. Central to this is the understanding of human variability as a function of responsiveness to social, cultural and physical environments (Dufour in press). Although such concerns were salient at the origins of anthropology as a discipline, they largely fell from consideration when the disciplinary divide took place in the early twentieth century. They re-emerged in the 1950s and 1960s within the adaptability frameworks that placed human evolution and ecology central to the understanding of human biological variation. They became formalized only in the 1990s, when the earlier adaptability framework was shown to need theoretical expansion in explaining how culture and behaviour shape human population biology through economic and political change, modernization and urbanization. Bioculturalism is therefore a return to nineteenth-century concerns by human biologists; however, it does so within frameworks created by important theoretical advances in evolutionary biology, ecology and human genetics in the second half of the twentieth century.

With the adoption of evolutionary and ecological frameworks in biological anthropology from the 1950s onward, some biologists again attempted to make systematic links between biology and culture. A landmark study in this respect was that of Livingstone (1958), who demonstrated links between malaria prevalence in African populations, genetic resistance to this disease in the form of sickle-cell trait, and the adoption of agriculture in prehistory as the environment in which such resistance emerged. Subsequently, the Human Adaptability Section of the International Biological Programme (HAIBP), instigated in the 1960s, aimed to document human biological diversity as fully as possible in many of the world’s populations, among them societies seen to be disappearing in the face of global modernization (Baker 1965). Of note is the HAIBP project carried out in Samoa, in which social and cultural environment was considered in relation to human biological variation in more detail than in any other HAIBP project (Hanna and Baker 1979). At a similar time, Katz and Schall (1979) elaborated an alternative version of the Livingstone (1958) model of genetic resistance to malaria, for populations in the Mediterranean region. In this, they proposed a biocultural adaptation involving fava bean consumption, malaria prevalence and resistance to malaria conferred by the Mediterranean variant of the glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency genotype. A number of human adaptability studies of the time attempted to demonstrate the fundamental biological criterion for assessing human adaptation, that of reproductive success. Natural selection was regarded as a much more important determinant of population genetic variation in the 1950s to 1970s than it was by the 1990s (Harrison 1997). Natural selection is difficult to measure and demonstrate in human populations, and investigators increasingly focused on ecological success as a better measure of fitness among humans than that of reproductive success (Ellen 1982). With this came increased emphasis on proximate markers of human biological success, such as nutrition and health, and increased awareness of the importance of social drivers of biological outcomes. Nutrition was clearly as much an outcome of subsistence practice, tradition, food choice and preference as of biological and physiological process. Health and disease could be seen as being socially constructed and/or biomedically defined. The emergent bioculturalism has been viewed in various ways. For example, Wiley (1992) described bioculturalism as biological research with social correlates, while Stinson et al (2000) have stressed the importance of both evolutionary and cultural perspectives in explanations of human biological variation. Furthermore, Goodman and Leatherman (1998a) have pressed for a broadening of biocultural study by integrating political economic approaches.

Current formulations of bioculturalism, as defined by Wiley (1992), Goodman and Leatherman (1998a) and Stinson et al (2000) privilege neither culture nor biology, and unlike sociobiology, do not seek to understand the evolutionary basis of human behaviour and culture. Rather, localized and measurable human biological outcomes are examined in relation to aspects of history, politics and economics, while past evolutionary outcomes are viewed as forming the genetic basis for biological responses to interactive physical, social and biological stresses in the present. The production of health and disease is also central to bioculturalism, and this forms the basis of ecological medical anthropology (McElroy and Townsend 2004). In this article, the emergence of bioculturalism from the adaptationist framework in biological anthropology is examined. It begins with a brief description of adaptationism, and the problems encountered with its use in attempting to understand biological variation in contemporary human populations. It is followed by an examination of bioculturalism as a theoretical framework that has emerged from it. This approach is then applied to the issue of food security among past and present populations of Coastal New Guinea, to illustrate two ways in which this framework can be used.

Human variation and the origins of adaptationism

Biological and cultural variation among human populations was of great interest in the nineteenth century, the Ethnological Society of Great Britain being formed in 1843 with the aim of scientific study of humanity in its broadest sense. Charles Darwin and other biologists such as Alfred Russel Wallace, Thomas Henry Huxley and Francis Galton were members, as was William Pitt-Rivers. Although Darwin (1874) proposed mechanisms of natural selection (Darwin 1859) to have operated to generate human biological variation, ideas of biological difference between human populations had become formalized into notions of race by the nineteenth century. The creation of racial typologies and the use of morphology and classification continued to be the methods of anthropology into the twentieth century, the physical anthropology of the first half of the twentieth century being concerned almost totally with palaeoanthropology, racial origins, typologies, affinities and classifications (Harrison 1997). The ideas of typology and classification were challenged and overturned in the second half of the twentieth century with the empirical testing of evolutionary and ecological mechanisms for human biological variation (Harrison 1997).

From the 1960s, human population biology sought to document and explain processes that contribute to human biological variability. The study of human populations on a comparable scale and intensity to those of plant and animal communities was still poor by the 1960s, and the HAIBP was instigated to extend ecological understanding to human populations. The aims of the HAIBP were defined in 1962 by Lindor Brown and Joseph Weiner as ‘a world-wide ecological programme concerned with human physiological, developmental, morphological and genetic adaptability’ (Collins and Weiner 1977). The central concept in this field was the idea of human adaptability, the ability of populations to adjust, biologically and behaviourally, to environmental conditions. The HAIBP intigated studies in 93 nations between 1964 and 1974 (ibid).

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there had been many non-medical biologists who sought to engage with broad human themes that considered both social and biological concerns. Similarly, in the 1960s the HAIBP was a point of entry for biological scientists to engage with human themes outside of biomedicine. The majority of work involved attempts to describe and understand human adaptation and adaptability as the ecological processes by which natural selection takes place (Collins and Weiner 1977). Ideas emphasizing plasticity (the ability to alter physiology and morphology within the individual lifetime) as central to adaptation also emerged in various of the HAIBP studies (Lasker 1969).

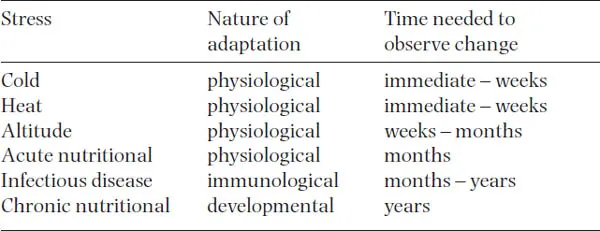

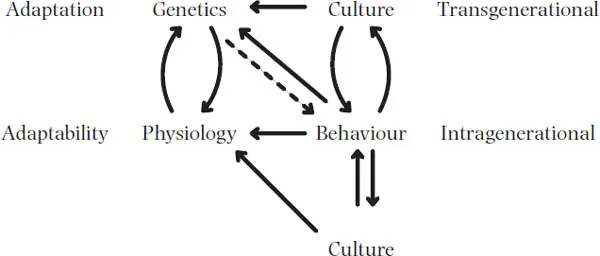

Adaptationist frameworks and their limitations

The adaptationist perspective is central to evolutionary biology and is one in which genetic, physical, physiological and behavioural characters are seen as being optimized in the adaptation of a species to its environment (Lewontin 1972). When applied to humans, adaptation and adaptability have been defined as processes whereby beneficial relationships between humans and their environments are established and maintained, making an individual better fitted to survive and reproduce in a given environment (Lasker 1969, Frisancho 1993, Harrison 1988, 1993). They have also been viewed as the processes that allow human populations to change in response to changing or changed environments (Baker 1965, Ellen 1982, Little, 1982, 1991, Smith 1993). With the HAIBP, behaviour and culture came to be increasingly incorporated in the adaptationist framework, with genetics and physiology (Ellen 1982, Harrison 1993) (Figure 1.1). In this scheme, genetic adaptation is seen to take place through selection of the genotype, the genetic structure of a population being shaped by migration, and differential fertility and mortality. Physiological adaptation is seen as the shorter-term changes that individuals and populations can make in response to any of a variety of environmental stressors, including heat, cold, low partial pressure of oxygen, low food availability, and infection (Table 1.1). Behavioural adaptation includes types of behaviour that can confer some advantage, ultimately reproductive, to a population. Such behaviours may include proximate determinants of reproductive success, for example mating and marriage patterns, types of parental investment (Dunbar 1993b), or patterns of resource acquisition, including food procurement. Cultural adaptation involves the transmission of a body of knowledge and ideas, objects and actions being the products of those ideas (Ulijaszek and Strickland 1993a).

Table 1.1 The time scale of some human physiological, immunological and developmental adaptive processes (modified from Ulijaszek 1997a)

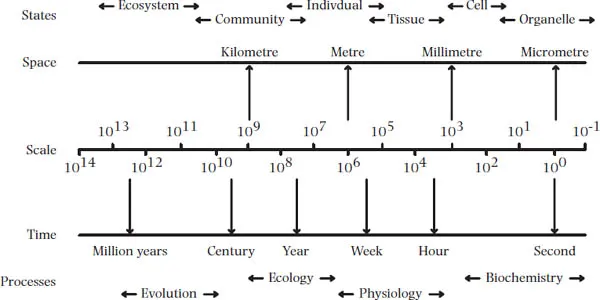

The HAIBP considered the fundamental questions of human ecology to be fitness, selection and population balance, as determined by physiological, developmental, and polymorphic adaptation, while acknowledging the problems associated with accounting for interactions between genetics and environment (Weiner 1966). However, operationalizing these questions was difficult. Adaptation can be seen as involving process and change, sometimes but not always in response to stressors, toward reaching accommodation with the environment. If adaptation is a process, then it must be possible to observe the process, or infer it from an observable character or trait. Adaptive processes can only be demonstrated if the duration of research is long enough to observe change; cross-sectional observation will only allow adaptive process to be inferred, not demonstrated. Problems associated with locating possible adaptive solutions of any population become apparent when framed in time and space (Figure 1.2). First, the notion of adaptation as state or trait must be distinguished from adaptation as process and change. The time-scale of human biological adaptation varies from fractions of a second to many generations, while physical states can be observed cross-sectionally at a range of levels, from macro- to micro-level.

Figure 1.1 Adaptive relationships (from Ulijaszek 1997a)

Field studies of short duration may be adequate to describe adaptive states, but not adaptive processes, given the long-term nature of many such processes. However, without knowledge of environmental change or stability, it is impossible to say whether the state described is one of adaptedness or not (Dobzhansky 1972). Table 1.1 gives the time scale needed to demonstrate the existence of adaptive processes to a variety of ecological stresses. Research has traditionally been of fairly short duration and rarely beyond a year, and it is of little surprise that adaptive processes have been extensively described in relation to cold, hot and hypoxic stresses (Frisancho 1993). Short-term physiological processes are the most researched and most thoroughly known, not only because they are easier to conduct, but also because they have been useful to the operationalization of military ambitions of various nation states including the United States and the United Kingdom. The understanding of short-term climatic adaptation was accelerated during the Second World War, when military concerns about the efficiency of operation of human military resources placed in extreme environments became important in new global theatres of war (Ulijaszek 1997a). The understanding of variation in human energetics and nutritional adaptation also has its scientific basis during World War Two. For example, the Minnesota starvation experiment was carried out to determine the physiological and psychological effects of human semi-starvation (Keys et al 1950), in an attempt to understand how best to undertake nutrition rehabilitation of starved victims of war. Over a 24 week period, the partial starvation of thirty-two adult male conscientious objectors was observed and physiological and pyschological change extensively documented, prior to nutritional rehabilitation. The value of this study for the understanding of human adaptation was not immediately appreciated by biological anthropologists. However, this changed as nutrition and subsistence practices became an increasingly important focus of research with the HAIBP (Ulijaszek 1996).

Figure 1.2 Ordering of time and space in the adaptive suite (from Ulijaszek and Strickland 1993a)

The question of what constitutes successful human adaptation has remained elusive, however. Since the measure of success is usually taken to be straightforwardly Darwinian (1859), it is necessary to demonstrate that specific alterations favour survival and reproduction. This has proved difficult to demonstrate in human populations (Smith 1993), Darwinian selection being more often inferred in relation to physiological traits which confer advantage. Adaptive processes related to changes in population genetics are cross-generational, and can only be inferred from trait biology or empirical study of distributions of genes or gene products (ibid). The study of trait biology involves examination of morphological and physiological factors that show marked geographical variation in their distributions, the task being to show that variants are each adapted to their own environmental circumstances (ibid). The empirical study of distributions of genes and gene products involves their spatial mapping, and relating these maps to potential selective pressures such as nutrition and infectious disease. An early example of this is Livingstone’s (1958) explanation of the linkages among population growth, subsistence strategy, malaria and the distribution of the sickle cell gene in West Africa. Another example is that of populations exhibiting genetic-based lactose tolerance in relation to milk consumption (Flatz 1987).

Another problem is the idea of the population as unit of study, which prior to the HAIBP was seen as synonymous with the idea of a society. Between the 1960s and 1990s, the study of human adaptation and adaptability moved away from essentialized notions of population biology, as such explanations for the existence of species were increasingly replaced by evolutionary ones in biology more generally across the second half of the twentieth century (Sober 1980). Explanations of variation within a species offered by contemporary geneticists involve citations of gene frequencies and the evolutionary forces that affect those frequencies. In the same way that no species-specific essences are required or posited for the current study of biological variation more generally, the understanding of variation in human biology requires no population-specific essence (see chapter by Dunbar, this volume). However, inasmuch as culture is seen as an adaptive force in human adaptability, the population construct has re-emerged in the guise of specific cultures, societies and ethnic groups. These have not undergone similar de-essentialization by biological anthropologists. Definitions of culture might include proximity, history, language and identification (Brumann 1999), as well as shared and socially-tansmitted normative ideas and beliefs (Alexrod 1997). However, culture as ‘norms and rules that maintain heritable variation’ (Laland et al 2000, Wilson 2002) as conceived in the adaptability framework has largely excluded the dynamism of social and cultural process. For example, values, beliefs and knowledge might or might not be consensual within a society, and the extent of consensus or lack thereof can have consequences for human population biology. Furthermore, cultures cannot be assumed to be natural, unchanging kinds (Atran et al 2005), leading to questions of how the long-term study of human variation in particular societies might be interpreted and understood.

The idea of environment in the adaptationist framework has also undergone change, increasingly including socially- and culturally-constructed environments. Humans manipulate and change local environments in their use of them and in relation to natural and social stress and social competition. Although some cultural structures may be seen as evolving as adaptive systems in response to environmental factors, culture is not primarily adaptive (Morphy, 1993). Furthermore, while behaviour may buffer against environmental stress effectively, environmental changes induced by behavioural responses often carry with them new stresses. In Wiley’s (1992) terms, adaptation in the broadest sense is ‘tracking a moving target’.

The reframing of anthropometry

The use of anthropometry in comparative physical anthropology had, in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, been largely to create or reify racial typologies. However, anthropometric descriptions of samples of adults and children have been useful in the determination of health risks of individuals and populations from the early twentieth century onward (Tanner 1981). The new biological anthropology embraced the idea of anthropometry as a measure of plasticity and nutritional health and rejected its use in taxonomy. According to...