eBook - ePub

The New Media Nation

Indigenous Peoples and Global Communication

Valerie Alia

This is a test

Share book

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The New Media Nation

Indigenous Peoples and Global Communication

Valerie Alia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Around the planet, Indigenous people are using old and new technologies to amplify their voices and broadcast information to a global audience. This is the first portrait of a powerful international movement that looks both inward and outward, helping to preserve ancient languages and cultures while communicating across cultural, political, and geographical boundaries. Based on more than twenty years of research, observation, and work experience in Indigenous journalism, film, music, and visual art, this volume includes specialized studies of Inuit in the circumpolar north, and First Nations peoples in the Yukon and southern Canada and the United States.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The New Media Nation an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The New Media Nation by Valerie Alia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Scattered Voices, Global Vision

We signed the papers with our thumbs.

As soon as the ink was dried, the surrounding

peoples challenged our treaties

and the fight began.

They told us to be self-sufficient after secluding us on a rock pile

—Robert Joe, Sr. [Wa-Wal-Ton], Swinomish [nation]

As soon as the ink was dried, the surrounding

peoples challenged our treaties

and the fight began.

They told us to be self-sufficient after secluding us on a rock pile

—Robert Joe, Sr. [Wa-Wal-Ton], Swinomish [nation]

Some of the world's least powerful people are leading the way toward creative and ethical global media citizenship. Locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally, Indigenous peoples are using radio, television, print, and a range of new media to amplify their voices, extend the range of reception, and expand their collective power. Emerging from the shadows of a shared colonial inheritance, the international movement of Indigenous peoples has fostered important social, political, and technological innovations.

I first used the term, “New Media Nation,” in a chapter for Karim Karim's edited collection on communication and Diaspora (Alia 2003). Emerging from the international movement of Indigenous peoples, The New Media Nation is linked to the explosion of Indigenous news media, information technology, film, music, and other artistic and cultural developments. While its individual member outlets and organizations may be subject to state regulations and control, in a broader sense, The New Media Nation is an outlaw organization. No real “nation” in the political science sense, it exists outside the control of any particular nation state, and enables its creators and users to network and engage in transcultural and transnational lobbying, and access information that might otherwise be inaccessible within state borders.

Like many of its constituent organizations and cultural groups, The New Media Nation uses a form of what the interdisciplinary, post-colonial scholar of ethics, human rights, and globalization, Gayatri Chakravorzty Spivak (1990; 1995), has called “strategic essentialism,” in which particularities and differences are set aside, in the interest of constructing an essentialized pan-indigeneity. Cultural action, the making and remaking of identities, takes place “in the contact zones, along the policed and transgressive intercultural frontiers of nations, peoples, and locales (Clifford 1997: 7).” Transnational connections break the binary relations of “minority” and “majority”, and renew earlier concepts such as W. E. B. Du Bois's notion of “double consciousness” (Clifford 1997: 255). Those who exoticize and primitivize Indigenous peoples may find these developments surprising. The Inuit journalist, Rachel Qitsualik, provides a cultural context for understanding the openness of Inuit and other Indigenous communicators to technological innovation and change:

Inuit are nomads…[and] rejoice in the ability to compare Opinions abroad, as they did when traveling at will…the hamlet is the new iglu, and the Internet is the new Land (Alia 2007).

Through creative use of strategic essentialism (Spivak 1995) and a wide range of media techniques and technologies, Indigenous people are developing their own news outlets and networks, simultaneously maintaining or restoring particular languages and cultures and promoting common interests. Their progress is consistent with Ien Ang's idea of the “progressive transnationalization of media audiencehood” (Ang 1996: 81). However, “transnationalization” implies a unidirectional crossing of national boundaries and, in my view, should be extended to account for instances of internal colonialism and for boundaries between ethnicities and regions. I have called the fluid, constantly changing crossing from boundary to boundary and place to place—the internationalization of Indigenous media audiencehood and media production—“The New Media Nation.”

Inuit have played an important role in this global communications movement, having developed some of the world's most effective and politically astute organizations. Indigenous people from many parts of the world regularly attend Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) assemblies as observers who often carry ideas and strategies home. Founded in 1977 by the late Eben Hopson of Barrow, Alaska, as the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, the ICC has flourished and grown into a major international non-government organization representing about 150,000 Inuit of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Chukotka (Russia). The organization holds Consultative Status II at the United Nations. On its website, the ICC explains its origin and mandate:

To thrive in their circumpolar homeland, Inuit had the vision to realize they must speak with a united voice on issues of common concern and combine their energies and talents towards protecting and promoting their way of life.

The ICC international office is housed with the Chair and each member country maintains a national office under the political guidance of a president (ICC website 2006).

The ICC declared its global vision from the start. During the Cold War years, Siberian Inuit were not able to leave the Soviet Union to attend ICC assemblies. But ICC was founded “under four flags” and each assembly flew them all. Each time, an empty chair was placed in front of the Soviet flag to symbolize the presence of Inuit from all of the circumpolar nations. Finally, in 1989, under Gorbachev's leadership, Inuit from Chukotka, Siberia, were permitted to attend the ICC assembly. It was held in Sisimiut, Greenland, and I was lucky enough to be there for one of the most moving experiences I have known.

Everyone gathered on the dock to greet the ferry when the Siberians arrived. Though happy, some of them were a bit wobbly, having reportedly endured 40-foot waves during the passage from the airport at Sondre Strømfjord to Sisimiut. Some of their hosts went out to greet the ferry in the large boats called umiaqs. The magnificent Greenland qayaq (kayak) team performed in their honor. Ashore, they were met with tears and laughter. They were granted provisional status and brought into ICC as full members at the next assembly. Every evening there was dancing, theater, and music. Inuit from Alaska and Siberia watched each other's performances and expressed their joy in meeting relatives for the first time. Some had been separated by only a short distance, through the boundaries set by governments that had long denied their cultural and often familial connection in the name of political expediency. In 1989, there were several chairs in front of the Soviet flag, and all of them were full. These days, the flag is Russian.

Figure 1.1. Mary Simon addressing the ICC General Assembly in Sisimiut, Greenland, 1989. To her left are delegates from Chukotka, Siberia (USSR, now Russia), who were attending the assembly for the first time. Photograph by Valerie Alia.

Rewriting the story

Recently, the spread of information and communication technology has given rise to new blends of traditions and elements of “world culture,” in music and arts, clothing fashions, food, etc. The coexistence of traditions and modernity is currently observed among many indigenous peoples worldwide. It includes renewal and in some cases reinforcement of ethnic identities, as well as an instrumentalization and commoditization of cultures…These new blends illustrate Marshall Sahlins's assertions, based on research in many parts of the Third and Fourth Worlds, that peoples around the world see no opposition between tradition and change, indigenous culture and modernity, townsmen and tribesmen. Culture is not disappearing, he concludes, rather it is modernity that becomes indigenized.

—Csonka and Schweitzer 2004: 51; Sahlins 1999

—Csonka and Schweitzer 2004: 51; Sahlins 1999

One example of Sahlin's view of indigenized modernity is a delightful booklet of historical and cultural information, which was published in 1989 by the Dene Cultural Centre in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories (Canada). The reader encounters indigenized modernity from the moment of seeing its front cover, with a picture of Indigenous people on a riverbank, watching a canoe go by, filled with strangers. One child is pointing to the canoe. The title fills in the rest of the picture—Dehcho: Mom, We've Been Discovered. Steve Kakfwi is a political leader from the Dene Nation. The back cover of the booklet carries his words:

Alexander Mackenzie came to our land. He described us in his Journal as a ‘meagre, ill-made people’…My people probably wondered at this strange, pale man in his ridiculous clothes, asking about some great waters he was searching for. He recorded his views on the people, but we'll never know exactly how my people saw him. I know they'd never understand why their river is named after such an insignificant fellow (Kakfwi, quoted in Holmes 1989).

The Dene call the river Dehcho, not the Mackenzie River. The booklet's text, design, and presentation make Sahlins’ point. Colonial and Indigenous history and culture are rewritten and presented for the education (and perhaps, the edification) of Outsiders and the gratification of Insiders in setting the record straight. The humor, too, is characteristic. It appears in all sorts of contexts and places, and offers a fresh way of communicating the issues. Another notable example is the Indigenous Australian film, Babacueria (1981), in which colonizers and the colonized are also turned around. The title is a satirical reworking of outsiders’ hearing of the term, “barbecue area”. In the film, a boatload of Indigenous “explorers” land on Australian shores and “discover” pale-skinned, English-speaking “natives.” The explorer-colonizers proceed to do all of the things for which colonizers are known. They plant a flag, attempt to communicate with the “natives,” rename and label people, things, and places in absurd and inappropriate ways, and then begin to “improve” the people they have found. From broadcast news anchors to government leaders and social service directors, they set new policies and controls, herd children off to residential schools, and engage in all manner of amusing and sometimes sinister activities.

The Fourth World Movement

The New Media Nation is one of the major trends to emerge from what George Manuel called the “Fourth World.” While the term is generally attributed to Manuel and is unquestionably linked to his vision of an international organization of Indigenous peoples, Mbuto Milando apparently coined it during a conversation. When they met, Milando was First Secretary of the Tanzanian High Commission. Manuel told him that if Indigenous peoples could stand together, their voices “could reach beyond their national borders and be heard by the world. Mbuto…suggested that what George Manuel seemed to be talking about was the emergence of a “Fourth World.” George Manuel seized on the phrase and over the years popularized it” (McFarlane 1993: 160–161).

George Manuel came from the Shuswap (Secwepemc), Neskonlith First Nation of British Columbia, Canada. He was equally passionate about working locally, regionally, nationally, and globally. Regionally, he served as president of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. He headed the National Indian Brotherhood (now the Assembly of First Nations). He was the first president of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples. In the late 1970s, he told 15,000 Indigenous Peruvians, “we have to have our own ideology” (Manuel and Posluns 1974: 77–78). His influences were as wide as his outlook. His thinking was affected by meetings with Julius Nyerere in Tanzania and with Māori leaders in New Zealand in the early 1970s. In 1973, he met in Washington, DC, with Mel Tomasket, president of the National Congress of American Indians. They set up exchanges between Indigenous people in Canada and the United States that became models for later developments in global and pan-Indigenous projects. Manuel was “'instrumental in drafting the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ and contributed to innumerable and highly influential national and international position papers and reports. To help unify Indigenous peoples of North, Central, and South America and Eurasia, he launched the UN-affiliated World Council of Indigenous Peoples in 1975” (McFarlane 1993: 8).

It was not his first international effort. In 1960, he and Henry Castilliou submitted a brief on British Columbia land rights to the United Nations. In 1973, he traveled with a delegation from Canada's Department of Indian Affairs to New Zealand and Australia. He found a historic colonial link between First Nations people of British Columbia and Indigenous peoples in Eurasia: in both regions, the first European to “make contact” was Captain James Cook. Both areas were subjected to settlement and “developed under the British imperial system” (Mc-Farlane 1993: 156). Manuel's tour of New Zealand ended with festivities organized by Māori that included members of some of the Polynesian peoples who had immigrated to New Zealand—Samoans, Tahitians, and Fijians, who shared a common culture with Māori (McFarlane 1993: 159). Before the time of PowerPoint, George Manuel and Michael Posluns created a narrated slide show of Manuel's Australia-New Zealand trip to promote the North American-Eurasian Indigenous project. In October 1975, the Nootka community hosted the first World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) conference on Vancouver Island. In attendance were 52 delegates and more than 200 official observers from 19 countries. George Manuel was acclaimed President. Vice President was Sam Deloria, from the United States. The rest of the founding executive comprised Julio Dixon (Panama), Clemente Alcon (Bolivia), Nils Sara (Norway), and Neil Watene (New Zealand) (McFarlane 1993: 218).

Manuel used the term “Fourth World” to clarify the position of Indigenous Peoples in relation to the layers of dominance and subordination, and centrality and marginalization of peoples within political power structures in the relatively privileged “First” and “Second” worlds and the “Developing” or “Third” world (Manuel and Posluns 1974; Bodley 1999: 77–85; Dyck 1985). Peoples of the “Fourth World” cannot be confined within national or state borders. For Manuel, language and communication help to engineer and maintain the oppression of Indigenous peoples. In the context of Fourth World theory, “Nation” refers to a community or group united by common descent and/or language (Murphy 2000). Manuel framed the Fourth World not as a place, but as a global highway. “The Fourth World is not…a destination. It is the right to travel freely, not only on our road but in our own vehicles” (Manuel and Posluns 1974: 217).

Fourth World: The Next Generation

However powerful a movement, progress tends to come in fits and starts. In 2007, “the new UN Human Rights Council adopted a declaration…to protect the rights of indigenous peoples around the world, including their claims on land and resources” (Schein 2007). While the declaration is not legally binding, many people have noted that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which also was not a binding document, eventually became customary law.

Ellen Lutz, executive Director of Cultural Survival, thinks the question of Indigenous “peoples” was “the main stumbling block. As indigenous advocates frequently point out, the whole debate is over the letter ‘s’” (Lutz 2007: 14). I think it is a bit disingenuous to imply that “Indigenous peoples” form as easily definable a category as “women” or “victims of disappearance.” In fact, the very question of whether or not to define indigeneity underlies the whole enterprise. There is no definition of “Indigenous peoples” in the Declaration, or in any other UN publication, body or procedure. Lutz says that this is deliberate, as a precise definition is both impossible and unhelpful. “Among indigenous peoples, inter-governmental organizations, and most states, consensus has emerged that it is better not to define ‘indigenous peoples’ and to focus instead on defining and protecting their rights” (Lutz 2007: 19).

Despite the frustration of knowing the decision was not unanimous, participants acknowledged it as an emotional moment of great political significance. “[T]he packed conference room erupted into applause. People wept and hugged each other and smiled broadly. Louise Arbour, the UN high commissioner for human rights and former Supreme Court of Canada justice, joined in the standing ovation” (Schein 2007). “In the end, the force for support was so great that even countries that had previously dissented, including Russia and Colombia, chose to abstain rather than vote against it. The only ‘no’ votes were from the diehard group of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States” (Cultural Survival Quarterly 2007: 5). In April 2009, under the leadership of newly elected Kevin Rudd, the Australian government reversed its position and endorsed the declaration. Despite a sharp change in direction from the presidency of George W. Bush to that of Barack Obama, the United States still had not endorsed the declaration (Cultural Survival 2009). For many, Canada's vote was a big shock. The newly (and only marginally) elected minority Conservative government of Canada rejected the request for a consensus decision, requested a vote, and then voted against the declaration.

Lawyer and Treaty Six international chief, Willie Littlechild said, “I'm very excited…delighted and encouraged by the signal the new Human Rights Council has given the world that they are serious about addressing indigenous issues.” Nevertheless, Littlechild and Kenneth Deer, representing the Mohawk Kahnawake First Nation of Québec and the United Nations Council of Chiefs, said they felt betrayed by the Canadian government. Deer said: “Canada had a lot to do with the declaration getting this far…It's ironic that for eleven years they carried the resolution and at the end they voted against the declaration and against their own work” (Schein 2007).

The New Media Nation is a Fourth World movement that is engaged with removing ethnic and national borders and placing pan-indigeneity at the center. Although culturally distinct, the world's Indigenous communities have collectively experienced many of the elements of Diaspora. Small numbers of people are scattered over great distances, some far from their homelands, as in Oklahoma-where survivors of forced relocation landed at the end of the “Trail of Tears,” and the high Canadian Arctic, where Inuit were moved from northern Québec. Some reside in homelands newly “legitimated” by dominant governments—as in the instances of Nunavut Territory and Greenland Home Rule. Some are in process of negotiating or renegotiating their relationships to state governments, as in the case of Indigenous people in Australia, in the wake of the 2007 government apology (discussed in Chapter 2). Arjun Appadurai (1990: 298–299) uses the term, mediascape, to describe media representations and their dissemination. Starting from Appadurai's idea of “mediascapes” and “ethnoscapes”—new flow patterns of media and people—John Sinclair and Stuart Cunningham observe that “whereas flows of people often have tended to be from the periphery…towards the “centre”, media flows historically have traveled in the other direction” (Sinclair and Cunningham 2000: 2). This is not always the case with respect to Indigenous media. Although dominant-society media made early incursions into Indigenous communities, the main movement in Canada has been from “periphery” to “core”—with Indigenous media originating in remote arctic and sub-arctic communities and moving gradually toward the urban centers. The most recent example of this pattern is the transformation of Television Northern Canada (TVNC), based in the minimally populated northern regions, to the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN), which covers all of Canada and is moving toward global coverage. The poverty and distortion of mainstream coverage have made it imperative for Indigenous people to develop their own news outlets. They are using satellite, digital, cable, the Internet, cell phones—whatever is at hand. This is not, as some might infer, an exclusively high-tech movement, but one based on maximizing the effectiveness of small- and large-scale technologies, organizations, communities, and budgets. Often, it is the older and simpler technologies—or a fluid mix of old and new, high- and low-tech—that best serve its needs.

Figure 1.2. The next generation: high school students join the staff of the Top End Aboriginal Bush Broadcasting Association (TEABBA), broadcasting live from the Gama Festival in Arnhem Land, Australia in 2005. Photograph by Michael Meadows.

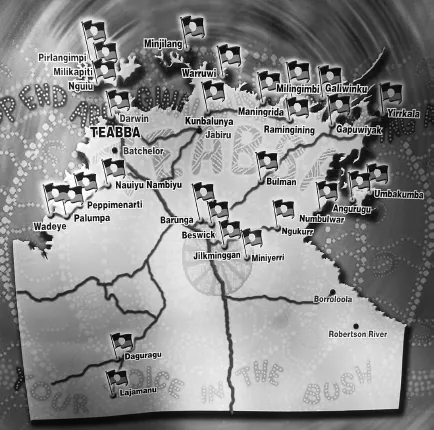

Figure 1.3. Radio stations served by TEABBA, across the Top End of Australia.

Radio remains the chosen medium for local communication, both in traditionally transmitted forms and transmitting via the Internet to expand and globalize originally locali...