![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: ‘Are we still together here?’

This book is based on fieldwork in Uhero in the Dholuo-speaking Bondo District of western Kenya at the end of the twentieth century.1 It examines late modern East African village life, looking particularly at the central role of everyday practices of material contact or touch for the constitution and contestation of relations, and for the construction and reconstruction of time. Underlying the significance of material contact is its connection with growth, of persons, groups and the forward movement of life more generally. As we shall show, for many people in western Kenya growth is engendered by material engagements among persons and between persons and things. Yet both the capacity of touch and the nature of growth are contested in Uhero, which is why they have become the analytical themes of this book. In the first part of this introduction, we provide an outline of these themes; in the second part, we reflect on our way to Uhero village and on how we arrived at some of these concerns.2

A community at the end of the world

To talk of Uhero is to talk of a group of people, JoUhero (914 persons in February 2001), attached to a particular place, a peninsula on Lake Victoria.3 Like all Luo, JoUhero have connections – practiced or fictitious – to distant places.4 Many of them travel widely, but home is never forgotten, although, for various reasons, people may rarely go there.5 Few of them are buried away from the home where they belong by birth or marriage, death being – at least in these days of uncertainty – the definite return home. The world beyond Uhero – cities, neighbouring nations, other continents – is present in Uhero in material objects that are used or longed for, in dreams of going abroad and in fears of exploitation. But, in spite of the considerable mobility of many JoUhero, at the centre of people's life world is still – and probably increasingly – the idea of ‘home’ (dala): a particular, named place of belonging and of a community of people attached to this place.

Yet, as the question in this chapter's title – asked in a conversation between young people – shows, the most salient trait of this community is its profound doubt in itself. Uhero is not usually evoked by either young or old as a coherent, stable and safe community, but in relation to the fractures and tensions between its members. Beneath these conflicts, what JoUhero share is a profound sense of crisis and loss. This undoubtedly encompasses what JoUhero call ‘the death of today’ (tho mar tinende) – the AIDS-related sickness and death of many villagers during the past decade or more – but this is seen as but the most recent outcome of longer processes of economic and social change that affect the very constitution of sociality itself. Nostalgia pervades everyday conversations, public oratory and popular music (Prince 2006), and generalising statements of loss are ubiquitous; either taken straight from Achebe/Yeats: ‘Things fall apart’ – words that generations of Kenyans have read in school – or in a local idiom: ‘The earth is dying. There is no love nowadays’ (‘Piny tho. Tinende hera onge’), which link the loss of life and belonging directly to that of social relations, continuity and sense of direction. Uhero calls forth, then, a sense of longing as much as of belonging.

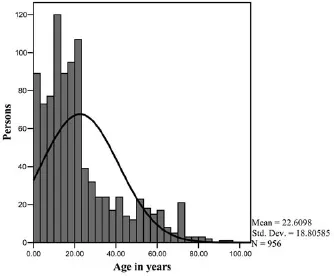

Laments about the ‘death of land’ and the decline of ‘love’ seem to be as widespread across contemporary Africa as the literary quotation. In Ghana, Geurts found frequent references to ‘worldly demise or something rotten and amiss in the universe’, expressing concerns with land degradation, AIDS, poverty and moral decline (2002: 112–14;183); de Boeck observed in post-Mobutu Congo ‘a deeply felt sense of personal and communal crisis which pervaded all levels of society’ and ‘a growing sense of loss of a viable basis of social relations’ (1998: 25; see also Gable 1995; Hutchinson 1996; Mamdani 1996; Yamba 1997; Ferguson 1999; Sanders 2001; Dilger 2003).6 JoUhero (as well as Luo people elsewhere) say this crisis started in the 1980s. This was a time of accelerating economic decline that disappointed the expectations of ‘development’ of the period after the Second World War, which had been encouraged by independence and the achievements of the new nation's first, progressive years. The 1980s were a time of authoritarian political rule, corruption, externally imposed austerity policies and economic decline that betrayed the promises of independence; and it coincided with a sharp rise in mortality due to deprivation and, increasingly, to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Since over 60 per cent of JoUhero are under thirty years of age (Figure 1.1), few of them have personal memories of better days. The Luo contemporary sense of loss, then, does not simply reflect an experience of change, but is also a distinct way of talking about people's sufferings and the challenges to survival in the present.

Figure 1.1. Age distribution of Uhero's population, December 2002 (n = 956).

What exactly has been lost people disagree upon. For some it is an idealised pre-colonial world of morally upright pastoralists, for some it is civil servants’ and wage-earners’ expectations of development, modernity and progress that seemed achievable in the 1960s and 1970s – and often Arcadian and Utopian longings merge. Accordingly, ethical arguments take on a temporal dimension: ‘These people don't do as they should do any more’; ‘Those people still do as it was good to do in the past’; and ‘Because people still behave like this, we have not yet achieved that future.’ Contact and continuity with the past, especially material contact in ritual and everyday practices, are widespread and contested concerns. Some people fear it, such as born-again Christians, who regard the African past as the ancestors’ (in their terms: devils’) realm. In contrast, others struggle to reconnect to the past by calling for the restoration of ‘Luo Tradition’7 or by trying to reconcile what they distinguish as ‘Christian’ and ‘Luo’ practices. Through these contested practices, different understandings of temporality are materialised in everyday life and engaged with each other. For the purpose of this study, the most significant fact is that, irrespective of people's particular orientation in time, tropes of loss have become a leitmotiv of conversations about sociality and change in Uhero and give shape to people's practices in the present.

They also shape imaginations of the future. How one creates families, marries and raises children, ensures their future, builds houses, uses one's property and arranges for its devolution, works the land to produce food or surplus, cares for one's body, provides for old age, cares for the sick and elderly, copes with illness, and buries and remembers the dead depends on how one understands the past and wishes the future to be. Orientations forward as well as back in time thus give shape and meaning to people's present practices and are equally contested. Conflicts and disagreements about personhood and social relations, property and durability, crystallise around people's attempts to bring about the futures they desire. Some dream of moving ahead, leaving past and origins behind, while others dwell on imaginations of return; but these are different orientations rather than characteristics of different persons and groups; people adapt positions contextually and move between these orientations, including contradictions and dilemmas, which guide their social practice in the present.

For JoUhero, these temporal trajectories from past to future are entangled with spatial trajectories spanning what in colonial times was designated as ‘reserve’, the rural repository of backward lifestyles; the Kenyan cities and farms, places of transformation and possibility; and the realm of remoter futures, Europe or the USA. In the second half of the twentieth century, after political independence, colonial separations between spaces of the past and those of the future were somewhat eroded, initially spurring people's mobility and their hopes of eventually arriving somewhere. However, from the 1980s onwards the present crises – in politics, health and the economy – have considerably challenged these movements and expectations. Suspended between past and future, the present continues to be imagined in terms of movement, journeys along the battered tarmac roads and railway lines, longed-for jet travel and virtual movements through letters, penfriends and, of late, for some, the Internet. But alongside this is a sense of immobilisation – no past to return to, no future to gain – which is well captured by young people's responses to the question of what they are doing: ‘I'm just sitting’ (‘Abetabeta’) – implying not working or moving – or ‘I'm just walking around’ (‘Abayabaya’) – without productive purpose or destination.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, this community on the shore of Lake Victoria finds itself at ‘the end of the world’, in both a locational and a temporal sense. This sense of being stuck in place and time does not, however, imply isolation. People see their predicament as part of a larger pattern; they recognise how wider currents with distant sources flow through and shape life in Uhero. Structural Adjustment and donor policies, (antiretroviral) drug prices and globalised medical research are issues of debate, as are Kenyan politics, government policies and corruption scandals, and the expansion of South African influence during the past decade – manifested in fish export, satellite TV, gold prospectors and rumours about child abduction – augments the spatial imagination. Yet the experience of being part of a larger whole, which affects people's lives but remains outside their control, being part of a process but unable to affect its course, exacerbates their sense of immobility and loss.

Although it is not our main theme, this book does necessarily have something to say about how people engage with wider, so-called global, processes of change, or modernity, a theme that has gained prominence in the anthropology of Africa over recent decades (e.g. Comaroff and Comaroff 1993; Moore and Vaughan 1994; Hutchinson 1996; Weiss 1996; Crehan 1997; Ferguson 1999). Some of these works emphasise the destruction resulting from the confrontation between local societies and global modernity (e.g. Fernandez 1982; Vansina 1990). Others celebrate the creativity of global modernity in peripheral African locations (and ignore its destructive sides) as if the engagement with wider connections were a specifically new phenomenon (e.g. Hannerz 1992; see also Appadurai 1986). Others again acknowledge that African and other modernities have co-evolved, and seek to replace the dichotomy between pre-modern African and modern Western societies and culture in favour of an analysis of ‘African modernities’ (e.g. Fabian 1990; Comaroff, J.L. and Comaroff J. 1991; Comaroff, J. and Comaroff, J.L.1997; Geschiere and Konings 1993). This book takes its orientation from accounts of African modernities that explore changing ideas and practices of personhood and social relations through observations of localised social practice, such as Piot's study of Kabre sociality (1999), Hutchinson's work on Nuer relatedness (1996) and Taylor's work on changing and contrasting imaginations of the body and practices of healing in Rwanda (1992). What these ethnographies share, despite their different approaches, is that they transcend the older ethnographic fiction of cultural or social otherness (e.g. between Africa and the West), not by collapsing them into the convenient sameness of a global ecumene, but by retracing within African societies the patterns of radical alterity that mark the predicament of modernity. In a similar manner, this book will focus on concrete everyday practices between JoUhero, and JoUhero's reflections about these practices and how they change, emphasising the diversity of experiences within this community (see Chapter 3). Despite the apparent clarity of distinctions drawn by JoUhero between ‘then’ and ‘now’, ‘here’ and ‘there’, ‘us’ and ‘them’, we argue that there are, in fact, no such clear-cut, easy distinctions to be had – especially in these times of confusion and death.

The death of today

Before we move on to lay out the main concepts explored in this book – growth and movement, touch and relations – we must address the place of the ‘death of today’ and of AIDS in the lives of JoUhero, as well as in this book. Death is omnipresent in Uhero, in fresh graves, deserted houses, and homes inhabited by very young and very old people. Saturday has become the day of funerals, which are the only social occasion of note. During our last longer fieldwork period (2000–2), seventy-seven JoUhero (forty-one women and thirty-six men) died, and thirty-seven of these were young adults (fifteen to forty-five years of age).8 Estimates for western Kenya suggest that, during the time of our fieldwork, 30–40 per cent of young adults were HIV-positive (KNACP 1998; UNAIDS 2000). This means that every third adult in Uhero will die within ten years unless a radical change of health care provision occurs. Young adults die before they are married or even before they have had children, and children are orphaned and left with relatives, old people, or to care for themselves. ‘Growth’ in the sense of ordered generational sequence can no longer be taken for granted.9

Yet, although death, presumably related to AIDS, is central to JoUhero's current sense of crisis, we choose not to place AIDS at the centre of this account. Until recently, ‘AIDS’ or ayaki (from yako, ‘to plunder’, ‘to raid’) were scarcely used terms in Uhero and, even in 2000, when one could hear them in private conversations and funeral speeches, this was rarely related to a particular person but to health problems in general. Even though JoUhero are keenly aware of the epidemic and its immediate causes, it is still not common for somebody's illness or death to be openly attributed to HIV. Instead, people say ‘she has been sick for a long time’ (or claim, more commonly, that this has not been the case). If AIDS is mentioned, it is after someone's death, since speaking the name of the ‘death’ while the sufferer lives would almost amount to a curse.

Moreover, for many people, the omnipresence of death is understood in a broader context, extending well beyond the biomedical facts of HIV/AIDS and originating in the ‘confusion’ (nyuandruok, from nyuando, ‘to confuse, jumble up, disarrange’) of social relations that the past century has brought about.10 This death is not merely a long-term side effect of modernity; it also reveals the impotence of modernity itself, as biomedicine offers no remedy for it.11 The defeat of modern science leaves JoUhero suspended between a lost past and a fading future. Well aware of the fact that treatment for AIDS exists for those who can afford it, JoUhero are left behind as, some of them say, ‘us poor Africans’.12 The understanding that ‘AIDS is our illness’, as one young JaUhero put it, ‘and not yours’, is reiterated and debated around the notion of chira, a deadly affliction arising from disordered social relations and affecting the growth of families. Thus, the death of today is understood within wider historical struggles about power and resources. Were we explicitly to centre this account on AIDS, we would suppress the critical potential of the villagers’ interpretations of their present condition and its genesis.

However, if we choose not to place AIDS at the centre of analysis, this does not mean that it is not present throughout this book. The bodily suffering and death of young people are experienced as opposed to any form of growth, creating a sense of being stuck, and opening up the question of what exactly growth is and how it should be produced. Moreover, AIDS makes certain kinds of material contact problematic and potentially dangerous – notably bodily intercourse, care for the sick and burial of the dead. But how exactly AIDS affects social relations and concerns with touch and growth is far from obvious, and this question occupies JoUhero as well as the pages of this book. AIDS brings many tensions and conflicts in social relations to a head, but the situation of this sociality cannot be reduced to it or explained by it. JoUhero's primary concern is not with death, but with growth and how to engender it against considerable obstacles.

As we shall argue, all kinds of substance – body and bodily fluids, food or earth – and all substantial ties established through touch and material contact have the potential to bring about growth; and they are all related to one another through metonymic associations. Every form of touch potentially evokes another one. Touch and sharing of substance in the sexual union have an important place in this metonymic cluster, but not the dominant one. Every substantial relation has the potential to create life and growth as well as to kill. Thus we contend that, only if we understand how a loaf of kuon (stiff porridge) is shared or not shared in modern Uhero, can we begin to examine bodily intercourse and its effects, including the problems arising from HIV. The specific problems that sex, reproductive fluids and AIDS pose in these times is implicitly present in our account, but to place it at the centre would be to distort the representation and would prevent us from understanding AIDS in this place, at this time: it is omnipresent, it enters all existing tensions and conflicts, but it is not the dominant theme. Uhero is not an ‘AIDS village’.

Growing relations

JoUhero agree that ‘there is no love these days’, sharing a sense of loss and – to a greater or lesser extent – of being lost, and locating this loss in the workings of their sociality. ‘Love’ (hera) should here be understood less as an emotion or attitude than as a practice, or, rather, the multiplicity of everyday practices through which people create and enact positive social relations. However, people do not agree about what human relations in their community should be like and blame different causes for their malfunctioning.13 People deal differently with the present predicament, and the same people may respond differently to different situations. Rather than framing our study in terms of ‘the consequences of social change’, or the effect of time on social relations (in Tönnies’ idiom of the dissolution of Gemeinschaft), we look at how images and debates about rupture and loss are used in relations, concretised in people's use of ‘time figures’ (pre-modern/modern, nostalgia/expectations, decay/development) in social practices and ethical reflections about practice. Undoubtedly, many things have changed in living conditions and people's ways of acting towards one another in the course of the ‘-ations’ of the twentieth century: colonisation, monetisation, commodification, Christianisation, modernisation, globalisation, individualisation (and, of late, Africanisation and Traditionalisation), and their concomitant phenomena: biomedicine and schooling, wage labour and private property, literacy and mass media, demographic change and epidemics. However, JoUhero rarely talk about the past in such linear terms; rather their memories emerge through everyday practices and evaluations of other's practice. People's position in the present and towards other people shapes their access to and use of the past and vice versa. Imaginings of rupture and continuity are realised through relational practices towards others and the environ...