![]()

CHAPTER 1

Setting the Stage

Indianism and What It Is Not

Reality in a world, like realism in a picture,

is largely a matter of habit.

—Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking

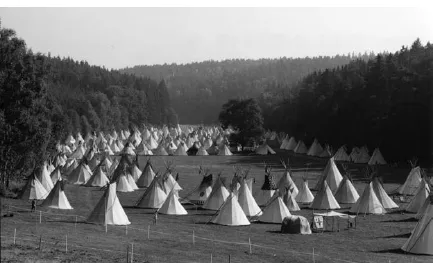

All over Europe, passionate amateurs invest time, effort, and love in re-creating scenes from a Native American past. Most numerous and active in Germany, these so-called Indian hobbyists or Indianists draw on ethnographies of North American Indians, travel diaries, paintings and photographs, how-to books, and faraway and perhaps imaginary landscapes and role models to sustain what has become an epistemological and performative practice with its own local traditions and dynamics. Organized in more or less tightly knit play communities, Indian hobbyists manufacture, display, wear, and use homemade replicas of eighteenth-or nineteenth-century garb and artifacts on “playgrounds” dotted with tepees (illus. 1.1) in an attempt to create visual, palpable, olfactory, gustatory, aural, and kinesthetic impressions of Native American or Canadian material cultures as they imagine these to have existed in the past. Since the establishment of the first Indian hobby clubs in the 1920s in Germany, Indianists have come to conceive of their hobby as a quest for knowledge. The drive behind the hobby is to try to understand material culture through experimentation. While fun and pleasure are often mentioned as an important reason for participating in the hobby, trying to “get things right” and be accepted by more experienced or gifted hobbyists may be a source of stress and frustration as well. The professed goal of the hobby is for participants to get a feel for how life was lived in the woodlands or on the plains back in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, respectively—which does not necessarily preclude singing folk songs around the campfire, organizing canoe trips with an “Indian” theme, or showing an interest in contemporary Native America.

Illustration 1.1. Indian Week 2003, Thuringia

Indianism as a Subset of Indianthusiasm

So how does this practice mesh with, to name a few examples, the small-business enterprise of a Dutchman performing “Indian stories” in a tepee pitched in Noord-Holland, the zeal of an activist claiming to feel a spiritual connection with Native Americans, or the delicate touch of a battle reenactor talking me through the materials he carefully selected for his Iroquois trapper's outfit? Indianists share the stage with thousands of Europeans who are active in other scenes that have a link with “Native America,” such as the characters I just mentioned, whom we will meet in more detail below. Many different practices, from contemporary powwowing to black-powder shooting to New Age drumming, have some overlap with the Indian hobby “proper.” Moreover, insiders may not always agree on what kind of an amateur should be considered an Indian hobbyist, let alone on what would constitute “the good Indian hobbyist,” with all the moral overtones that this implies.

A discussion of Indianism would be a muddled affair without an attempt to clarify where insiders position themselves within this wider spectrum. We need to know both what sets Indian hobbyism apart (as an experience) and what is perceived to set it apart (as a phenomenon) from other expressions of interest in Native America in order to understand why it seems especially prone to provoke mirth or disapproval in outsiders and pleasure or stress in insiders. Singling out the phenomenon as a “distinct” category will of necessity remain a somewhat artificial exercise, as even Indianists do not always agree on the core activities and values of their hobby. Moreover, trying to zoom in on the typical features of Indian hobbyism carries the risk of fostering stereotypical images of “the Indian hobbyist.” The interest of this exercise lies in unraveling the discourse about Indianism by addressing some of the most tenacious misunderstandings that transpire from outsider perceptions of the hobby, and in paving the way for a discussion of identity-through-performance.

A useful term to invoke here is “Indianthusiasm,” coined by Hartmut Lutz, a professor of Native American studies in Greifswald, to refer to all kinds of nonpolitical expressions of interest in historical or imaginary North American Indians among European, especially German, amateurs. He defines his term, translated from what he calls in German Indianertümelei, as follows:

The term Indianertümelei signifies a yearning for all things Indian, a fascination with American Indians, a romanticizing about a supposed Indian essence, or, for want of a better translation that catches the ironic ambiguities of the German term, an “Indianthusiasm.”…German “Indianthusiasm” is racialized in that it refers to Indianness [Indianertum] as an essentializing bioracial and, concomitantly, cultural ethnic identity that ossifies into stereotype. It tends to historicize Indians as figures of the past, and it assumes that anybody “truly Indian” will follow cultural practices and resemble in clothing and physiognomy First Nations people before or during first contact. Relatively seldom does Indianertümelei focus on contemporary Native American realities.1 (Lutz 2002: 168–69)

Lutz, then, speaks of practices that are problematic and tainted by stereotypical conceptions of “the Indian” (usually the Plains Indian), a European construction in itself.2 In what follows, I will take the liberty to extend his very convenient and catchy term to a much wider realm. In my usage of it, for now leaving aside some possibly essentializing and historicizing aspects of the practices under discussion, I will consider not only the Indian hobby, but also European activism on behalf of Native Americans or professional interest in North American Indians as expressions of Indianthusiasm. I find it useful to do so because these practices, even if they differ significantly in content and focus, arguably sprang from a shared history of ideas and images that have become part of European consciousness.3 In my communication with European activists and (museum or university) professionals, they often implied or expressed a motivation for being involved with Native American cultures that they could not always “rationalize” and that seemed to be rooted (almost in spite of themselves) in a long European tradition of contact and fascination with North American Indian cultures as distinct from other indigenous cultures. In their personal stories, they would recall having “played Indian” or savored romantic novels about the West before becoming involved in the subject matter in a more “serious” and responsible manner—a coming-of-age that is often mirrored in Indian hobbyists’ personal accounts as a transition from “beginner” to “expert.”4

I will carve out this conceptual niche for Indian hobbyism by giving a short overview of different forms of Indianthusiasm in my country of origin, the Netherlands.5 I spent quite some time looking for Dutch Indianists, who proved to be scarce on the ground. Instead, I encountered many people involved in or fascinated by “things Indian” who would not consider themselves Indian hobbyists and often, in fact, reacted disdainfully to any mention of the phenomenon. Self-identifying terms that surfaced in interviews with these other enthusiasts were, rather than “Indian hobbyists,” Indianenvrienden (friends of the Indians), Indianenliefhebbers (amateurs of the Indians), and Indianenfreaks (Indian buffs or enthusiasts). By approaching the phenomenon from outsiders’ perspectives, I hope to paint a picture of discourses that Indian hobbyists are in general well aware of, and which they actively use in constructing and verbalizing their own identities as distinctive actors competing for a slice of the excitement and prestige that involvement with Native America still tends to convey in Europe.

At the same time, painting a picture of Dutch Indianthusiasm will provide an impression of a Dutch outlook and mentality in which I inevitably partake as a product of “Dutch society,” despite having spent a considerable part of my adult life abroad. Thus, an overview of Dutch Indianthusiasm both draws on and illustrates my status in part of this research project as a “native anthropologist” who enjoyed TV series about the American West and played cowboy as a child. This being said, most of my Dutch examples of Indianthusiasm have equivalents in other European countries, which makes the following overview safe to resonate more broadly throughout this book as a sample of the wider Indianthusiast context in which European Indianists perform their specific practice.

Dutch Indianthusiasm: Support Groups

beyond Beads and Feathers

Several small-scale support groups for North American Indians are active in the Netherlands. Some of them share a founding history but parted ways as a result of differences over goals, philosophy, or strategy. In light of the shrinking popular interest in Native American issues, mentioned by most representatives of these groups, they have become competitors for members and sponsors. In early 2003 I spoke with the presidents of De Kiva, NANAI, Lakotastichting, Arctic Peoples Alert, and Wolakota Stichting,6 all located in the western, densely urbanized part of the Netherlands, and asked them to elaborate on their groups’ history, goals, and membership, as well as their experience with what I tentatively called Indianenspel (Indian play) or Indianisme (Indianism) and described as the expression of a historically focused interest in Native American cultures through craftwork, dress, and reenactment.

The oldest support group for North American Indians in the Netherlands is De Kiva, which was founded in 1963 and has published an informative magazine with historically and ethnographically oriented contributions ever since (cf. Taylor 1988). The founder of De Kiva, Mr. Heijink, had had contacts with Dutch anthropologist Herman F. C. ten Kate Jr. (1858–1931), who carried out physical-anthropological and ethnolinguistic research among Native American tribes and collected ethnographica for the ethnology museum (Museum voor Volkenkunde) in Leiden.7 One long-time Kiva member had personally witnessed performances by “show Indians” touring with Buffalo Bill and the German Circus Sarrasani; as we will see, such Native American performances were a major impulse for the foundation of the first hobbyist clubs in Europe.

De Kiva currently focuses more on contemporary issues concerning Native Americans and First Peoples and is involved in small-scale aid projects, especially to stimulate the continuing use of Native American languages. At the annual Kiva Day that I attended in the fall of 2003, elaborate presentations on travel experiences in “Indian Country” alternated with reports on aid projects. A bookstand with an impressive collection of literature on Native Americans (including many English titles) did good business. Two Dutch women selling crafts on behalf of associates living on a Native American reservation shared the space with a Dutch artist who made portraits of Native Americans and animals. One Kiva member told me she was interested in beadwork and had once organized a craft workshop.

In 1972, as Native American activism started to receive international attention, a Kiva member who wanted to be more actively involved in aid projects founded the NANAI support group. NANAI publishes NANAI Notes, a newsletter focusing on contemporary Native Peoples in North America. In tune with contemporary trends in Dutch society, its focus became pragmatic rather than idealistic, with a humanitarian rather than an activist focus. Sponsors of NANAI (the foundation has no members) had very different backgrounds, I was told, as did members of De Kiva. They often harbored rather romantic ideas about Native Americans, NANAI's president mentioned, which was part of the attraction of supporting NANAI. To illustrate NANAI's pragmatic and flexible approach, he stressed that the organization did not eschew collaboration with non-activist and even commercial enterprises if this helped promote interest in and support for Native American projects. One example was NANAI's collaboration with the Dutch teller of “Indian stories” who performed in a tepee.

The Lakota Stichting (Lakota Foundation) was founded in 1989 by a member of both NANAI and De Kiva with the aim of organizing “responsible” trips to Lakota homelands. According to the website, participants in these travel projects have the unique opportunity to enter into direct contact with Native Americans, their culture, contemporary way of life, self-image, and history.

Arctic Peoples Alert is the support group with the clearest activist profile. It originated in a project in which both De Kiva and NANAI participated and evolved into a protest movement against military low-flying exercises above Innu land in Labrador and Québec, in which the Dutch air force participated. When low flying became less of a priority toward the end of the 1990s, attention shifted to other problems faced by indigenous peoples in arctic regions.

Finally, I contacted the Wolakota Stichting, a foundation dedicated to the support of the Steiner School for Lakota Children on the Pine Ridge reservation in North Dakota. Eric Sellmeijer, one of the two Dutch initiators and directors of the foundation, told me he felt a spiritual connection with Native Americans that he considered part of his identity. He spoke at length about his close friendship with a traditional Santi Dakota, whom he had visited several times. He had started out with a rather “romantic, stereotypical” image of the North American Indian as personified, for example, by Winnetou, the noble Apache in the late nineteenth-century adventure novels by Karl May. This German author is very often mentioned in connection with European Indianthusiasm, both in literature on the subject and by different brands of enthusiasts, including Indianists, often as a source of pleasure and excitement in which they indulged during their youth.8

Sellmeijer, then, shares the genealogy of his interest in Native America with Indianists; also, material aspects of his involvement resonate with the Indianist focus on material culture as I introduced it above. On the walls of his living room, a buffalo skin was on display, as were two watercolors he had painted depicting Native American themes. He had enjoyed fashioning a pipe bag and a beaded pouch adorned with a Dutch symbol, the tulip. In fact, his interest in Native Americans was expressed both through his involvement in the Wolakota support group and through his pleasure in owning and fashioning Native American artifacts and images. He was puzzled, however, by the apparent need for dressing up displayed by some admirers of Native American cultures, although he took pleasure in wearing a bowtie and a beaded ornament his Santi Dakota friend had given him.9

My other discussion partners representing Dutch support groups expressed similar concerns with Indianism as a practice that involved non-Native people dressing up as Native Americans. “Why don't these people just act normally?” one sighed. For want of a better term, another referred to it as Indiaantje spelen (“playing Indian,” with a childlike connotation implied in the diminutive Indiaantje) and criticized Indianists for not being interested in what really mattered—namely, contemporary Native American issues. De Kiva's president was more nuanced when asked about Indian hobbyism. In former days, he told me, part of the membership enjoyed making nineteenth-century-inspired costumes and artifacts, but this practice had been all but abandoned by active Kiva members.10 Perhaps, he suggested, the Dutch, lacking German romanticism, were too down-to-earth for “real” hobbyism (that is, replica making and dressing up). As far as he knew, they tended to dismiss such practices as a nonserious preoccupation with “feathers and beads.” The president of the Lakota Stichting, who was otherwise quite critical of Indian hobbyism, told me she could not help admiring some of the replicas she had seen on eBay.

Dutch Indianthusiasm: Idealist Pragmatics

in Commercial Enterprise

The Dutch have often been characterized as a merchant people combining a businesslike, pragmatic mentality with humanitarian ideals derived from Calvinism.11 In my search for commercial arenas of Indianthusiasm, I came across a number of arts and crafts and New Age—oriented shops that had equivalents in all of my fieldwork countries, but I was also introduced to two commercial players that struck me as typically Dutch. Walas BV and Sunka Tanka were commercial ventures driven by, as I was told, strong yet pragmatic principles.

Walas BV

I got my first impression of Walas BV from an attractive magazine the company produces for children, Baribal, which many of my informants praised for the quality of its design and content. Its goal, I was told by the managing director, was to show children that indigenous cultures were very much alive and to offer an alternative image to the usual presentation in museums, where such cultures were, in her opinion, often framed as something of the past. In primary schools and community centers, young children in the Netherlands are regularly exposed to popular representations of “Indians” that do not attempt to problematize easy stereotypes. In the Heemskerk local paper, Zondag Ochtendblad (23 February 2003), I read an announcement of “Indian days,” where the promised activities included making headdresses and dream catchers, braiding hair, painting tepees, storytelling, and savoring Indian snacks. Friends in Overschie, near Rotterdam, told me about an “Indian day” at their children's primary school, where they were encouraged to decorate ...