eBook - ePub

The Patient Multiple

An Ethnography of Healthcare and Decision-Making in Bhutan

- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan, medical patients engage a variety of healing practices to seek cures for their ailments. Patients use the expanding biomedical network and a growing number of traditional healthcare units, while also seeking alternative practices, such as shamanism and other religious healing, or even more provocative practices. The Patient Multiple delves into this healthcare complexity in the context of patients' daily lives and decision-making processes, showing how these unique mountain cultures are finding new paths to good health among a changing and multifaceted medical topography.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Patient Multiple

Cures, Healths and Bodies

Introducing a Bhutanese Patient

Early on in my ethnographic explorations of patient narratives in Bhutan I was struck by a problem. The ‘patients’ I worked with were using an array of healing practices, sometimes simultaneously, to cure their disparate health issues. The problem was that patients were so flexibly connected and constituted by multiple practices and knowledges that they fluidly changed subjective categories. Just when I thought I knew what a patient was and how they were being created, a new, contradictory or disjunctive subjectivity would emerge. Let me use Pema to illustrate the problem.

Pema and I worked together throughout my time in Bhutan, discussing the variations of her treatment history surrounding a painful and chronic nasal pain. She had visited the state biomedical hospitals, which had given her a diagnosis, medical records, medications and an operation. This single-track healing narrative augmented over time: two years later she arrived at the traditional medicine hospital with a bleeding nose and a resurgence of pain. She believed the biomedical doctors had failed as they hadn’t dealt with the Buddhist aspects of the disease, and she hoped for a more fitting cure from these traditional doctors. Over the course of this one illness, Pema had already shifted her ideas of what the disease was, where it had come from and how it was to be cured.

Taking Pema’s narrative complexity further, she then revealed she had another simultaneous pain in her stomach, however, this pain and causal disease was dissociated from her nasal issue. In her opinion, this disease had more to do with her astrological reading, or she called it her tsi (rtsis), and accompanying enviro-behavioural risks. I witnessed her bisect her body into two, both parts of which felt pain in different ways, explained through different understandings of health and curative practices.

How was I to deal with such multifarious patient subjectivities and ethnographic realities? To make matters worse, Pema was not a one-off case. In 2013, the Ministry of Health reported that its national healthcare centres treated just under two million cases, including returning and new patients in both traditional and biomedical medicine units (MoH 2013a: 66). In 1985 this number was below 350,000 (MoH 1986: 19), demonstrating a massive growth in the availability and use of national healthcare services. Meanwhile in February 2012, the popular Bhutanese newspaper Kuensel released an article quoting ministry figures that showed there were more alternative healers than all the doctors, nurses, health assistants and national traditional medicine staff nationwide, 1,683 to 1,593 respectively (Pelden 2012b). While these exact figures are contestable, they suggest a high demand for alternative healers as well as state healthcare services; across Bhutan, the sickly and those that act as decision-makers on their behalf are turning to many different healthcare practices to alleviate suffering.

This expansion and diversification of treatment routes in Bhutan parallels shifting ideas of health and healthiness. The arrival of new communication technologies, improved education and accessible health services in the past sixty years are just some of the factors influencing these changes. Not only are new modes of understanding and interpretation available – for example, with increased education and biomedical knowledge patients can now read and share their blood test results – but also new bodily interactions and modes of practice are easily accessible. Patients hook themselves up to dialysis machines, insert themselves into herbal steam baths or swallow new ranges of pharmaceuticals and herbal remedies. The new patient subjectivities emerging through shifts in both practice and knowledge are crucial in understanding healthcare-seeking behaviour.

The aim of this chapter is to argue for a theoretical conception of a ‘patient’ that will then play out through all following chapters, adding an important analytical position in understanding how people in Bhutan form coherent and effective responses to suffering in a diverse and rapidly changing medical scenario. I will draw from my ethnographic work with Pema, a nineteen-year-old woman with complicated and ongoing illnesses, as she ‘becomes’ and ‘emerges’ as a patient. I will describe how illnesses occurred in Pema and, through the course of their unfurling, through pain and understanding and in the company of different doctors, family members, healers and diagnoses, how she became not one patient but many patients, the ‘patient multiple’. Through this narrative I will also introduce Bhutan’s healthcare context, including the primary healthcare assemblages that go on to affect how, when, where and why patients seek out and participate in healing technologies, ethics, knowledge and practice.

The geographic contexts for the ethnography presented in this chapter, as well as the others, are the Thimphu and Mongar dzongkhags. However, the findings have implications and representation in many other areas of Bhutan. Latour’s actor network theory explains how to ‘transfer the global, the contextual, and the structural inside tiny loci[,] . . . allowing us to identify through which two-way circulations those loci could gain some relevance for others. [And secondly it allows us to] transform every site into the provisional endpoint of some other sites distributed in time and space[,] each site becom[ing] the result of the action at a distance of some other agency’ (Latour 2005: 219). With this theory of network expansion, I defend the extrapolation of my ethnographic findings into wider communities and socialities in that Pema, as well as many other patients and doctors, have lived in other regions, towns or villages, some of which I visited while tracing healing narratives. With road networks and medical transport services increasing, patients now move across the country in search of a cure (see Tashi 2009). Additionally, both state and alternative health practices are relocating to and operating within communities in even the remotest of Bhutan’s regions. While this chapter and many others will engage with geographic specificity and its affects on the ethnography, the two-way movements of agents – both human and nonhuman across a network, in this case the growing patterns in patient and health knowledge migration – permit a wider overview.

The chapter is broken into three sections, each introducing aspects of becoming, processes through which Pema becomes a ‘patient multiple’.

The first section introduces the ‘cure multiple’, in which we learn about the variety of different health practices that Pema uses and relates to as strategies against suffering. I will argue that Pema uses multiple cures to meet her different health needs.

The next section explores the different conceptions of ‘health’ through which Pema assesses her own ‘healthiness.’ I will claim that Pema has multiple ‘healths’ that are afflicted by correlating diseases, which in turn require correlating cures.

The final section pertains to the role of the body in the process of becoming a patient, and how Pema has many bodies that both fall ill and ameliorate in different ways.

I conclude by describing how Pema retains a sense of coherency while living these multiples of cure, health and body. Furthermore, I argue that her use of multiple healing practices brings an agentive meaningfulness to her healing experiences.

While the triadic structure I deploy here suggests distinctive boundaries, these sections should not be analytically or ethnographically dissociated. They are all interrelated and interdependent, and sometimes they may be the same thing. Following Deleuze and Guattari’s principle of connections and heterogeneity, ‘any part of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be’ (Deleuze and Guattari 2004: 7). I treat the patient as a ‘multiplicity’ or ‘rhizome’, and thus adopt the theoretical idea that ethnographic subjects of enquiry are integrally connected to other subjects, or rather they are constituted by ‘relations of exteriority’. For example, Pema’s biomedical body part may detach itself from a bloodwork report and reattach itself to a religious modality of health. Her red blood cells are removed from the biomedical epistemology and mean something different in a karmically contingent cosmology.

My narration of Pema’s illness is not limited to a chronological order, for it has been and continues to unfold over the course of one life that is still, at the time of writing, being lived. It began in the past, is occurring now and is being planned for in the future. It thus cascades itself across time, and I will treat it as such.

Furthermore in aid of arguing the muteness of chronology, my role as ethnographer must be considered. This story unfolded in my presence, as I sat with Pema during many consultations and treatments. It was revealed in interviews and informal discussions. Details were also communicated spasmodically, either during a phone call or a random meeting in the city. My learning of her story was not linear. Although my excessively zealous approach to interviewing attempted to sequentially obtain all the details of Pema’s life at our first meeting, I quickly learned that systematically recording Pema’s life in one interview was not feasible. In now writing Pema’s healthcare narrative, I have found that sequencing her becoming a patient is also superfluous work, for the patient multiple does not lend itself to a linear or neatly packed chronology of events through time. The event of ‘becoming’ a patient has time, occurs in time, but is not dependent on chronological sequencing, or any sequencing for that matter; different orders and patterns of time are called into play when a particular chronology helps enact the patient of that moment. Therefore my method of relating Pema’s story is purposely non-sequential so that our understanding of her will remain flexible and multidimensional, allowing me to introduce her as a ‘patient multiple’.

Cure Multiple

Pema and I met in a small wood-walled room in the National Traditional Medicine Hospital in Thimphu ready to spend the next hour discussing her reasons for visiting the hospital. She agreed to talk with me after her consultation, as did all participants who joined the research project. She had visited the hospital because of a resurgence in chronic nasal pain and was starting a treatment course with a drungtsho (drung ‘thso), the official name for a traditional physician in the traditional medicine institution. She was nineteen years old, a diligent and successful student from the Paro Valley, visiting her family and boyfriend in the capital city, although the boyfriend was a well-kept secret. She stood tall, nearly six feet in her high-heeled shoes, framed in a golden kira (dkyi ra), the female ankle-length national dress. My first questions searched for her beginning as a patient: When did her symptoms start? When did she first visit a hospital? When did she first ‘emerge’ as a patient? In her response, I found there was no ‘beginning’ in Pema’s interpretation. She has always had people care for her using multiple forms of curative practice, and thus has been a patient as long as she can remember. However, one particular illness experience was singled out quickly as her most dramatic and memorable to date.

PEMA: I was living with my parents in Paro, attending school. When I was twelve years old I was having headaches and fainting all the time. I was eating lots of medicine. Whenever I went to hospital they gave me paracetamol and vitamins. They said I was very weak and I should be eating vitamin C and taking lots of water and food so I wouldn’t faint. I felt quite better with the paracetamol, but only for two to three days; after that again it comes. My uncle told me I should go to Thimphu and take an x-ray. I was thirteen . . . I went to the Thimphu hospital and took an x-ray. When the doctor saw my x-ray he told me that I had got a sinus problem and I had to do an operation.1

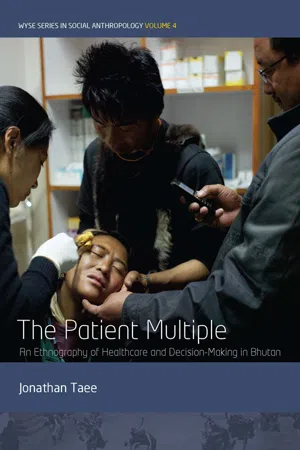

Illustration 1.2 Patient in Surgery; Operation Theatre One, Mongar Hospital. A young female patient lies on an operating table.

Pema’s first narration tells the story of a one-track healing response. Pain occurred, and treatment was found. Through more interviewing, I learnt that the biomedical hospital had diagnosed Pema with acute sinusitis caused by a slight anatomical deformity in her ethmoidal sinuses, just between her eyes, where bone was blocking the sinus openings.2 She underwent endoscopic surgery to remove small portions of bone to unblock the sinuses, followed by a heavy course of antibiotics to stop post-surgical infection.

If ethnography was easy and if all healing narratives were this simple we could stop at this sequence: pain → diagnosis → treatment → healed. However, I met Pema in the traditional hospital six years after her operation. Her chronic nasal pain was resurfacing, and this time she was visiting a different hospital, utilizing a different type of medicine. Not only that, she had formed new hypotheses for what the disease was and what part of her ‘health’ it was affecting, beyond just the symptomatic pain. This is just the beginning of a long and intertwined ethnographic account of Pema’s illnesses and how she assembles a curative response. I came to learn that throughout adolescence Pema had participated in multiples of healing practices and would continue to do so over the year we spent talking together.

Pema, like all patients across Bhutan, has access to a plethora of healing practices. When sickness strikes she may choose from a range of responses and may often participate in multiple curative routes. She may assemble her healing trajectories from state-managed hospitals and health units, non-institutionalized healers, home remedies, corner-shop pharmacies, religious practices, dietary changes or familial care, to name but a few. As Bhutan continues to open its borders to trade and development opportunities, so increases the influx of foreign and domestic health-related materials and practices, the sole focus of chapter 5. Pema has resources that neither her parents nor grandparents had that increase her access to these new health solutions. She is highly educated, now studying at a top Bhutanese college, and has an outstanding literary competency. The bus she takes from Thimphu to her college uses newly constructed roads that are constantly expanding access to more remote regions. In her kira pocket she carries an ample supply of Bhutanese ngultrum3 (dngul kram, the national currency abbreviated to nu) provided by her parents, who both work for the civil service, the biggest single employer nationwide, and thus she has disposable income for new medications and health products. With multiple cures arriving at her doorstep and the increasing means to access them, she regularly makes use of a diverse array of healing practices.

How can we conceptualize Pema’s use of these multiple cures and understand what it means to be a ‘patient’ of these practices? Annemarie Mol has shown medical anthropology the importance of ‘enactment’, how ‘medicine enacts the objects of its concern or treatment’ (Mol 2003: 5). Following this theory, ‘patients’ emerge through the practices they enact. Without a practice, a patient is simply a sick person, a fleshy body deteriorating. This is more than just an abstract relation; it is a use of the body with technologies, people, epistemologies, knowledge and experience. A patient ‘emerges’ through the enacting of healing technology, ethics and regime and is thus relationally dependent upon the practices engaged with. With the diversity of practices available to Pema, she had to be categorically flexible, multiple, able to move between these relational enactments and be reborn within each practice. This is why it is so important to understand the various practices available to patients, as they will in turn define what we come to understand as the ‘patient’ and how that ‘patient’ understands themselves.

Categorizing healing practices can be difficult because of the diversity of practices that may be considered as healing, curative or preventive. The problem is both an ethnographic and a theoretical one. Ethnographically it can be challenging to distinguish a healing practice from something that may have nothing to do with ‘health’. For example, would we consider T. Dorji’s (2004) explanation of restoring a person’s lost soul (la tor, bla stor), a practice common in Bhutan and detailed in chapter 4, as a healing or spirito-religious practice, or both? Would the practitioner who screams the name of the forlorn and bargains for the return of the ‘life forces’ (sog, srog, T. Dorji 2004: 598) consider it a health-related practice? There are even more mundane practices that an ethnographer might consider as a technology of healing: eating particular foods, circling a bus around a chorten at the top of a mountain pass or drinking ara4 (a rag), home-distilled alcohol, hot and with butter and an egg. With the right lens, almost all human activities can be connected to concerns of health; it often depends on how far one is willing to go to connect the dots.

This ethnographic diversity makes it difficult to theoretically manage an assortment of practices. Clumping together or bisecting practices into categories or modalities risks either missing meaningful connections between them or conversely homogenizing variance. While this is a semantic concern dealt with by many medical and social anthropological theorists (Napolitano and Pratten 2007; Strathern and Stewart 2010, to name two of many), it also holds weight in the ethnographic s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps, Illustrations and Figures

- Acronyms

- Notes on Language, Transliteration, Transcription and Translation

- Dzongkha Reference Guide

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Patient Multiple: Cures, Healths and Bodies

- 2. Modernizing Traditional Medicine: A Two-Option Healthcare Service

- 3. An Ethnography of Decision-Making

- 4. Alternative Practices and the Removal of Ja Né

- 5. Patients and Healing Materials: Relations and Dependency

- Conclusion: Assembling Patient Multiples and Complementary Logics of Care

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Patient Multiple by Jonathan Taee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.