eBook - ePub

Creativity in Transition

Politics and Aesthetics of Cultural Production Across the Globe

- 366 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creativity in Transition

Politics and Aesthetics of Cultural Production Across the Globe

About this book

In an era of intensifying globalization and transnational connectivity, the dynamics of cultural production and the very notion of creativity are in transition. Exploring creative practices in various settings, the book does not only call attention to the spread of modernist discourses of creativity, from the colonial era to the current obsession with 'innovation' in neo-liberal capitalist cultural politics, but also to the less visible practices of copying, recycling and reproduction that occur as part and parcel of creative improvization.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

AFRICAN LACE

AGENCY AND TRANSCONTINENTAL INTERACTION IN TEXTILE DESIGN

Over the last fifty years a colourful fabric popularly known as ‘lace’ has come to define the public appearance of Nigerians at home and in the Diaspora. The industrially produced and largely imported fabric is commonly considered in Nigeria today as ‘traditional’ material and has become an essential feature of festive and official clothing. From an outsider’s perspective, ‘lace’ seems to characterize the ‘national’ costume of Nigerians if something of this kind exists in such a varied, populous and multiethnic society. Indeed, the fabric can be seen to connect the diverse cultural landscape of the country, as it is tailored into differing ethnic clothing styles and thereby becomes the thread that acts as a common denominator, weaving together the external appearances of the people.1 In essence an ‘invented tradition’ (Hobsbawm and Ranger 2009), the newly introduced fabric forms the ideal base material for clothing styles that have become an expression of postcolonial Nigerian-ness: a marker for a new and prospering nation.2

The term ‘African Lace’ is borrowed from the business world within which production companies and resellers clearly differentiate between embroidery products targeting Euro-American and African markets. African Lace is a specific product that has developed over the last fifty years and has been constantly readapted to changing fashion trends in Nigeria, which is the largest African outlet for this kind of material. As such, its history of production and consumption exemplifies the movement and appropriation of creative ideas across continents.

The Origin of African Lace

In Nigeria the term ‘lace’ denotes what, from a technological point of view, are industrially produced embroideries. The misleading term came into use for early products made of guipure (chemical lace) or eyelet embroidery that closely resembled real laces. Real laces are produced by braiding on bobbins or by crocheting work, both techniques producing a fabric just by intertwining yarn. In the specific guipure embroidery technique mentioned, the ground textile is chemically dissolved, thereby producing a similar effect.

Industrial embroidery production has its roots in Switzerland. Inspired by the hand-embroidery skills of Turkish women, Swiss merchants introduced the craft to the region around St Gallen during the mid-eighteenth century (Längle 2004). From there it soon spread to the neighbouring Austrian province of Vorarlberg. The invention of the chain-stitch machine and, in the late nineteenth century, the shuttle embroidery machine allowed the expansion of production and created a specific product that inspired European fashion at the turn of the twentieth century.3 The small market town of Lustenau, close to the Swiss border, soon became the centre of the Austrian embroidery industry and competed by producing goods at a lower price range than their Swiss neighbours.

The major product of the industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was whitework embroidery used for underwear, women’s clothing, handkerchiefs or home textiles. The industry had always been export-driven and was constantly looking for new markets in Europe and the world.4 In the late 1950s, the Vorarlberg embroiderers developed an interest in Africa and reached Nigeria in the early 1960s, where a newly established Austrian trade representation offered support services.5 Probably from the 1930s on, women in Nigeria had been using industrial embroideries for white blouses worn with wraparound skirts made of locally woven fabrics. Such whitework embroideries in European designs were imported by British, German, Dutch, Lebanese or Indian trading houses located on the Niger Coast and sold through retailers across the country. Products from Austria probably already figured among their assortment, as large quantities were sold to export companies in Great Britain and the Netherlands. However, the Austrian manufacturers were not aware of the final destination of these exports.

After Nigerian independence, Austria opened a diplomatic mission in Lagos in 1962-1963 and created the office of a trade delegate within the embassy, seeing the wealth of the new country as an opportunity for the Austrian economy. By coincidence, the first trade commissioner, Heinz Hundertpfund, was native of the westernmost region of Austria, Vorarlberg, where the embroidery industry was located. He observed the use of white lace for blouses in Nigeria and alerted embroiderers in his home region about a possible business opportunity. This was further facilitated by the introduction of direct flights to Lagos by Lufthansa and Swiss Air in the early 1960s. On the Nigerian side, independence not only favoured the establishment of a wealthy middle class, but also spawned other developments that facilitated international business contacts.6 Nigerian merchants increasingly took the initiative to circumvent commercial agencies established during the colonial era from which they had, until then, bought their goods. They preferred to establish direct contact with producers in Europe in order to increase profits and exert control over the design and quality of the goods.7

Thus, the origin of African Lace can be traced back to Switzerland where, by appropriation of an embroidery technique of Turkish origin, a European fashion was born. As a result of technological innovation, part of the production was moved to Austria in the search for cheaper labour. There, a competitive industry developed that finally reached out to postcolonial Africa, where a new and promising market evolved. New flight connections relativized spatial distance and enabled closer transnational ties between production centre and market outlet. All these processes, characteristic of globalization (Eriksen 2007), had a crucial impact on the creation of the final product, as will be shown in this chapter. Over more than fifty years, the transnational connections between Austrian manufacturers and Nigerian patrons further intensified with accelerated communication culminating with the spread of Internet access and mobile phone connections, leading to a further compression of time and space that shapes creative outcomes.

Nigerian Clothing Traditions: A History of Transformation

In everyday parlance in Nigeria a broad distinction is made today between ‘African’ and ‘European’ styles of dress. Since the early twentieth century, European clothing has become ever more widespread in daily life, and in certain office professions, such as banking, it remains the obligatory dress code. Nevertheless, so-called traditional clothing continues to dominate the overall image of urban life. The term ‘traditional’ in relation to clothing is used in Nigeria to refer to what are conceived to be non-European dress styles. It references something precolonial or something grounded in local traditions as opposed to foreign appropriations. As will be outlined in this chapter, much of what is understood as traditional today was actually inspired in the past by foreign models or materials. So in a sense we can speak here of a myth of tradition that actually defines modernity because ‘modern styles’ of dress can also be tailored in ‘traditional’ materials, such as hand-woven narrow-strip textiles or locally dyed adire fabrics, which may be seen as both modern and traditional at the same time. There is no strict opposition between the two, no unilinear process of movement from one to another, but rather, a contemporaneity with complex ramifications (see also Ferguson 1999).

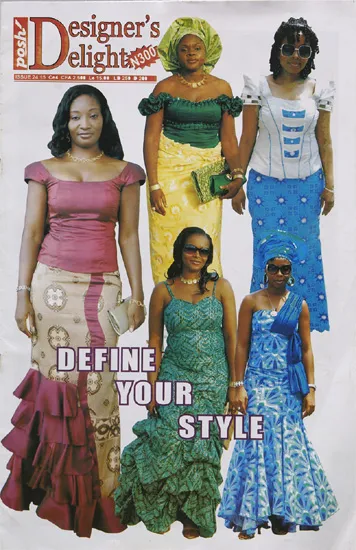

Within the sphere of contemporary ‘traditional’ clothing, certain types of fabrics are commonly associated with specific styles of dress, but such conventions are in constant flux, triggered, not least, by the creative reinterpretations of well-known fashion designers. Everyday women’s attire in what they usually refer to as ‘African’ or ‘traditional style’ consists in general of three pieces: a tailored blouse with a skirt that extends to the ankle, dubbed ‘up and down’, and a head tie of the same material (see fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Samples of contemporary ‘Up and Down’ styles on the cover of the fashion magazine Designers Delight (Issue 24, 2010).

The close-fitted blouses and skirts are fashioned in a variety of styles following the current fashion or suiting personal taste. Industrially printed cotton material (ankara)8 and resist-dyed cloth (adire) are predominantly used for such ensembles. The male counterpart in Nigerian dress consists of the sokoto, a long pair of trousers, and buba, a waist-length shirt with round collar (see fig. 1.2).9

The collar is usually bordered by delicate machine embroidery and has a short button panel. Muslims prefer to wear this shirt in a longer version reaching the lower leg. This style, dubbed ‘Senegal’ in the south, is also worn by non-Muslims according to personal preference or occasion. This variety of everyday attire for men is made of ankara or adire, but also from certain fabrics whose qualities are considered as characteristic of ‘male materials’ that are not usually worn by females. In the north, imported cotton damask (called brocade or, more specifically, Guinea brocade, in Nigeria) in white or pastel colours, such as light blue, beige and light green, is favoured for this outfit. In the south of the country, a variety of lightly structured cotton cloths are employed in the same restrained tones, sometimes also finely striped or delicately patterned in designs similar to those commonly used for male western shirts.10 This Nigerian dress in airy male-style materials is favoured by urban businessmen and politicians; it is well adapted to the local climate and cherished by many as an elegant alternative to the European business suit.

Figure 1.2. Contemporary male outfit designed by the well-known Lagos designer Goodwin Mekuye. Photo: Moussa Moussa, © Austrian Embroidery Association.

On special occasions, what is categorized as traditional clothing takes another form, and differs from everyday dress in cut. For festive events, women wear a wide, straight-cut blouse with round collar and long sleeves, a long wrapper and a matching headdress.11 The cut of this ensemble has remained identical for almost a century, so it could be categorized as a ‘classic style’, occupying a similar position to a woman’s suit in a Euro-American context. Although it can be made of ankara or adire, for festive occasions in southern Nigeria it is tailored in aso oke, a hand-woven narrow strip cloth, or more often in imported embroidery textiles, the so-called lace (see fig. 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Lady’s suit, Nigeria c. 1975. Industrial guipure embroidery with cotton yarn. Collection Weltmuseum Wien. Photo: Alex Rosoli.

The matching head tie needs to be made from a stiff material, either new styles of aso oke or colourful damask called brocade in Nigeria, and tied in a manner to achieve voluminous proportions. Older ladies will supplement the ensemble with an iborun, a cloth made out of the same material as the headdress. This cloth is folded over one shoulder, draped over the lower arm or wrapped around the waist. Men’s suits are of the same cut as those for everyday use, but are made predominantly of industrial embroideries. On official or special occasions, men of higher social status or age will wear an additional robe over the ensemble of shirt and pants. This voluminous gown in the Hausa style, known among the Yoruba of the south as agbada, and in the north as babban riga, is made of the aforementioned materials or of damask, the so-called Guinea brocade, and is usually decorated on the front and around the neckline with elaborate hand or machine embroidery. Completing the outfit is a cap, the fila, which in the south is made of aso oke or the stiff damask matching the women’s headdresses, and among the Hausa is adorned with characteristic embroideries. The expensive industrial embroideries are tailored in such ‘classical’ styles because these are regarded as more long-lasting, thus justifying the expense.

The quantity of cloth used for festive attires and draped around the body amplifies the wearer’s physical presence and enhances his or her social status. For this purpose, stiff materials that lend the garments a sculptural dimension are favoured. This predilection may relate to body ideals of fullness and plenty that also define age and associated higher status in society. At the same time, the voluminous gowns of men, with their pleats and heavy embroidered decoration, emphasize their elevated position in society, as family head or wealthy individual. The magnificent clothes also define their wearer’s movements: the adjustment and repeated tying of the wraparound skirt or energetic flinging back of the heavy fabric over the shoulder pertain to a subtle performance and staging of the self, in itself a creative act (Borgatti 1983).

While these ‘traditional’ forms of dress are common throughout Nigeria, they coexist with ethnic or local styles that clearly denote the wearer’s origins. These local styles are mainly worn at festive and official occasions and are often made of lace. Edo men, for example, wear a two-piece suit consisting of a shirt with stand-up collar and a long puffed-out skirt, while traditional women’s dress is composed of a wrapper that is tied above the breast and a wig decorated with agate or coral beads. Dress styles in the Nigerian south are characterized by their hybrid nature and by the use of a variety of materials ranging from locally produced hand-woven or -coloured materials to a variety of imported fabrics and styles, all of which contribute to the constitution of what is considered as distinctively Nigerian. These dress styles, connoted in Nigeria as ‘traditional’, assumed their present form only after the country’s independence, that is, since the 1960s. Yet, although there is little documentary evidence of the history of precolonial clothing traditions in Nigeria, we know that such practices of appropriation are not new or a result solely of colonization, but relate to trade interactions that go back over centuries.

Long before the Portuguese reached the West African coast on their way to India in the late fifteenth century, trade relationships had connected Europe and Africa through the Sahara.12 The trans-Saharan and later the Atlantic trade brought a huge variety of fabrics of North African, European and Indian manufacture to West Africa. The coastal trade was initiated by Portuguese seamen in the late fifteenth century and continued with Dutch and British merchants from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. From the time of the first trade contacts, European traders adapted their selection to suit the taste of African customers (Kriger 2006: 34). Most sought after were fabrics unknown loc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction Creativity and Innovation in a World of Movement

- 1. African Lace: Agency and Transcontinental Interaction in Textile Design

- 2. Heads Against Hands and Hierarchies of Creativity: Indian Luxury Embroidery Between Craft, Fashion Design and Art

- 3. The Social Life of Kottan Baskets: Craft Production, Consumption and Circulation in Tamil Nadu, India

- 4. Art and the Making of the Creative City of Chennai, India

- 5. Approximation as Interpretive Appropriation: Guaraní-Inspired Ceramics in Misiones, Argentina

- 6. Positioned Creativity: Museums, Politics and Indigenous Art in British Columbia and Norway

- 7. ‘We Paint Our Way and the Christian Way Together’: Transforming Yolngu and Ngan’gi Art through Creative Ancestral-Christian Practice

- 8. Undoing Absence through Things: Creative Appropriation and Affective Engagement in an Indian Transnational Setting

- 9. ‘The Eye Likes It’: National Identity and the Aesthetics of Attraction Among Sri Lankan Tamil Catholics and Hindus

- 10. Narratives, Movements, Objects: Aesthetics and Power in Catholic Devotion to Our Lady of Aparecida, Brazil

- 11. The Art of Imitation: The (Re)Production and Reception of Jesus Pictures in Ghana

- Afterword

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Creativity in Transition by Maruška Svašek, Birgit Meyer, Maruška Svašek,Birgit Meyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.