![]()

Chapter 1

Identities, Interests, and Ethnic Mobilization

This chapter has two objectives. First of all, it will set the general context of this study by reviewing some of the most important current descriptive literature on the Roma. In order to create an ethnic movement, organizations and individual activists need to specify their ideas on two crucial components of political action: identity and interests. With regard to the Roma, it may therefore be asked: What is Romani identity? And what issues should Romani activists try to place on the public policy agenda? These are questions that have plagued many activists consistently. Later in this book, I will examine how Romani movement organizers in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia have responded to them; how they have demarcated the boundaries of Romani identity and defined their interests. Answers to these questions have not only been given by activists, however; they have also been increasingly formulated by academics and other external observers. The writings of the latter are not merely important within the confines of academic study; they have clearly left an imprint on nonspecialist literature, popular thinking, and the views of the activists themselves. Before turning to the central actors of the Romani movement, it is therefore useful to start with an outline of the dominant ways in which academics and specialists have understood Romani identity and Romani interests.

The second purpose of this chapter is to lay out the theoretical framework of the study by asking what general theoretical approaches are applicable to the dynamics of Romani political mobilization. To do so I canvass the current theories concerning ethnic mobilization. There is a specific branch in social movement literature that has focused on the emergence and development of national and ethnic movements. In the latter part of this chapter, I discuss this literature and critically examine the three broad sets of factors that authors increasingly emphasize: political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and the processes of perception and interpretation.

Romani Identity and Interests: An Overview

Romani Identity

There have been many discussions on identity-related topics in Romani studies. One minor approach has been to consider the name “Roma” as a constructed category, and not as an entity in reality. Will Guy (2001b), Judith Okely (1983), Michael Stewart (1997), and Wim Willems (1995) are some of the scholars who have adopted categorization perspectives that are more or less similar to the one I propose. In most of their work, these authors have tried to understand Romani identity not as a matter of biology, lifestyle, descent, or any other group characteristic; but rather as the product of classification struggles involving both classifiers and those classified as Roma. That is also how they have considered a plethora of other group labels: Gypsy, Zigeuner, and Tsigane; their equivalents in the Central European languages such as cigán, cikán, cigány, and so on; and the appellations that have served to label subidentities such as Kalderash, Manush, Caló, Vlach, Romungro, Beash, Sinto, etc.1 A characteristic of most of these names, and certainly the more widespread ones, is that they carry with them a myriad of negative and romantic connotations. The introduction of the term “Roma” therefore clearly represents an attempt to break away from social stigmas and to produce a more positive, more neutral, and less romanticized image. In this sense, the usage of the name Roma is closely connected with the process of Romani political mobilization. Consequently, the name cannot be separated from the movement. Nicolae Gheorghe and Thomas Acton, both academics who have been involved in the international Romani movement, were hinting exactly at this aspect when they noted the following:

Not all those politically defined as Roma call themselves by this name; and some of those who do not, such as the German Sinte [sic], outraged by what they perceive as claims of superior authenticity by Vlach Roma, even repudiate the appellation Roma. The unity of ethnic struggles is always illusory; but to the participants the task of creating, strengthening and maintaining that unity often seems the prime task. (Gheorghe and Acton 2001: 58)

Not all authors, however, have shared this view. On the contrary, there is a strong tendency in the literature to understand Romani identity in terms of real common properties and objective characteristics. Perusing the work of the most influential authors writing within this tradition, one can roughly distinguish three main conceptualizations of Romani identity. These conceptualizations are not universally regarded as mutually exclusive, but they do represent quite distinctive perspectives.

The first defines the Roma as a historical diaspora. Scholars such as David Crowe (1995), Angus Fraser (1995; 2000), Ian Hancock (1992; 1997), and Donald Kenrick (1978) have all—in one way or another—understood the Roma to be a once bounded but now fractured community with common historic roots and common patterns of migration. What they have done is far more than simply search for historical evidence confirming the presence of the Roma; they have instead claimed a past through assuming the existence of the Roma as an enduring historical subject. They have usually viewed the Roma as the descendents of a population that traveled from the Punjab region in northwestern India and arrived in Europe at the end of the thirteenth century. A well-known proponent of this hypothesis is the Romani activist and linguist Ian Hancock. In comparison to those of many others, his theory is surprisingly specific. Hancock believes that the “ancestors of the Roma were members of the Kśiattriya or military caste, who left India with their camp followers during the first quarter century of the second millennium in response to a series of Islamic invasions led by Mahmud of Ghazni” (Hancock 2000: 1). Hancock’s idea is based mostly on linguistic investigation and builds on a research tradition that goes back to the latter part of the eighteenth century. At that time a number of people in different places—most notably the German historians Johann Rüdiger and Heinrich Grellman—for the first time forged a link between the Romani language and the Indoaryan languages of India (Fraser 2000: 21) and contributed to the idea of the Roma as a people (Volk).2 The idea of the Romani language as evidence for the existence of a once intact, original Romani culture in India was dominant among scholars studying Roma throughout the nineteenth century. It even served as a basis for the establishment in 1888 of an academic collective in England under the title of the Gypsy Lore Society.

The diaspora perspective has not remained above criticism. The two most prominent critics have been the anthropologist Judith Okely and the social historian Wim Willems. Okely (1983) has suggested that linguistic connections to Indian languages need not necessarily point to the Indian provenance of the group, since the language itself could have traveled along trade routes between East and West without the actual migration of an ethnic group “carrying” that language. According to Okely, the tendency to take the diaspora perspective for granted unnecessarily puts a large number of different people under the same category and sets them apart from European culture—in other words, it “exoticizes” them. She claims that such a perspective also inhibits good scholarly work on this subject since it neglects the group’s own criteria for membership (Okely 1983: 13).

Willems (1995), on the other hand, has focused not on the categorized but on the categorizers. His work has dealt in particular with the role of the classic “gypsiologists” (Heinrich Grellman and George Borrow) and the Nazi psychiatrist Robert Ritter in creating “the Gypsies” as a people with common origins in India. Willems has argued that current ideas of the Roma as an ethnic diaspora have their basis in a process of deliberate fabrication that started in the eighteenth century and reached well into the twentieth century, involving “gypsiologists” as well as governmental, judicial, and religious authorities.

The second conceptualization of Romani identity has focused on issues of lifestyle and behavior. Jean-Paul Clébert (1972) is one of a number of authors who have alluded to the idea that Roma are to be recognized by their desire to travel. Similarly, Angus Fraser (1995), Ian Hancock (1992), Jean-Pierre Liégeois (1994), and Andrzej Mirga and Lech Mróz (1994) have referred to other common cultural practices (elements of religion, habits, rules of cleanliness, musical traditions, etc.) and interpretations of the world (sometimes called Gypsiness, řomanipé or romipen) as allegedly objective elements of ethnic group identity. One author even suggests that on the basis of the standards of ancient Romani traditions, a distinction can be made between “orthodox” Roma and those who conform less to common cultural practice (Barany 2002: 13). A radical version of the lifestyle perspective argues that the Roma are related to one another exclusively in terms of their behavior; it concludes that for this reason they should not be seen as an ethnic group. Some of the arguments put forward in Lucassen et al. (1998) could be read in this way, especially when the authors argue that authorities applied the word “Gypsy” to groups that were not related in any ethnic sense but shared an itinerant lifestyle. Most versions of this perspective in Romani studies, however, accept the existence of Romani ethnicity and even agree with the thesis of a common Indian origin. Their emphasis is not on the common origin in itself, but rather on its effects on matters of lifestyle and habits.

The existence of a typical “Romani lifestyle” is sometimes referred to by those advocating the introduction of special rights for the Roma. For example, Colin Clark has argued that the nomadic way of life of those known as Gypsies and Travelers in the United Kingdom is a lifestyle that should not just be retained, but one that “should be respected and even promoted as a valid and legal way of life” (Clark 1999). Unfortunately, however, some of the writings that fall within this perspective have been pivotal in preserving stereotypical thinking about the Roma as inherently nomadic, marginal, “untrustworthy, primitive, childish and sorely in need of firm guidance and control” (Fraser 2000: 21). The notion of an allegedly intrinsic connection between Romani identity and deviant social behavior has frequently appeared in policy documents ever since the first large-scale assimilation campaigns in the Austrian empire under Maria Theresia (1740–80) and Joseph II (1780–90). In current academic literature one sometimes finds allusions to the idea that Romani identity revolves around a preference for marginality. In 1972, for instance, an article in Urban Life and Culture called the Roma “an outstanding example of a people . . . whose culture allows them to survive and even flourish in relatively impoverished environments” (Kornblum and Lichter 1972: 240). On the subject of nomadism, it is remarkable that the idea of the Roma as a wandering people has proven persistent even in the face of empirical evidence refuting such a view. Today the overwhelming majority of those who are seen as Roma in Central Europe live in settled communities—as their ancestors have done for many years. Still, romantic stereotypes of them as wanderers abound.

The third conceptualization focuses on the issue of biological kinship. Whether all Roma are genetically related is a vexed question. In 1992, Ian Hancock argued that this was indeed the case by stating that the Roma made their journey from India to Europe “intact” (Hancock 1992: 139). According to Hancock, the absorption of non-Roma into their ranks during travel “can account for some of the factors which distinguish one [Romani] group from another, [but] it has not led to the dissolution of the Roma as a genetically related people” (Hancock 1992: 134–35). This view is, of course, closely related to the diaspora perspective, but unlike that approach, the biological perspective emphasizes the supposedly natural bonds within and among small, tribal communities. Romani identity is here primarily defined along lines of alleged genetic or phenotypic characteristics. For Hancock, promoting this view is clearly part of an endeavor to emancipate the Roma. Assimilation policies of the past were often based on the argument that the Roma do not constitute a separate “ethnic” group, but are merely vagrants who have isolated themselves from mainstream society. The concept of genetic kinship, in Hancock’s view, serves to refute that argument.

But biological theories of ethnicity remain extremely controversial. Not only are they reminiscent of the racist ideologies of the nineteenth century; they also remind us of the type of racial ideology that marked the rise of Nazism in Europe and the eugenic movement in the United States. More specifically, reference to the alleged biological deficiency of the Roma is closely associated with the eugenic work on Roma done by the infamous German youth psychiatrist Robert Ritter and his associates in the latter half of the 1930s (Willems 1995). Inspired by Nazi ideology, Ritter tried to establish a link between heredity and antisocial behavior. He argued that “Romani genes” had affected the German “race” and in this way had led to the creation of people “of mixed blood” (Zigeunermischlinge). According to Ritter, most of the Roma in Germany were “of mixed blood” and, in the context of Nazi belief in Rassenhygiene (racial hygiene), needed to be completely eradicated (Burleigh 2000: 372–74). This view provided license for a practice of sterilization, deportation, and mass murder (Benz 2002; Nečas 1999). During the war the Roma became a target for total genocide, and survival was often solely dependent on the level of local non-collaboration in the various areas of Europe under Axis control (Lutz and Lutz 1995). Biologists now recognize the fallacy of biological determinism and the invalidity of the concept of “race” as a natural perceptual scheme or a biological category (see, e.g. Allen 1990; Gilroy 1998; Tucker 1996); there is as much genetic variation within what we call racial groups as there is between them, writes Lawrence A. Hirshfeld (1996). Yet the idea of the Roma as a biologically distinct and naturally inferior group remains surprisingly persistent. It is heard frequently in everyday talk, and, what is perhaps even more alarming, it continues to surface in some of the darker corners of the academic literature.3

As the above overview illustrates, a classification of the literature according to three ways of circumscribing Romani identity cannot be anything else than a blunt analytic tool for exploring a complex and heterogeneous field of academic discussion. Many authors have looked at the Roma in more than one way, and some of them have, of course, changed and adjusted their views over time.

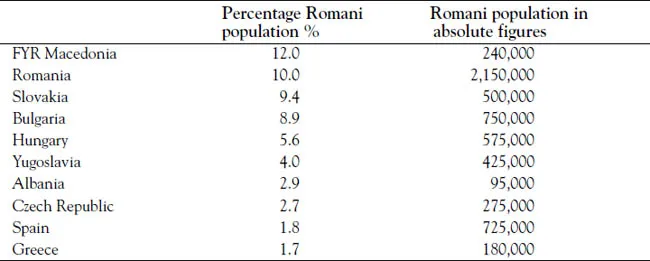

Given the disagreement among scholars about what constitutes Romani identity, it is not at all surprising that there has also been some degree of polemic concerning the number of people said to possess that identity. To offer an idea of the size of the Romani minority in Europe, it is customary among activists, governments, and academics to present some of the available population statistics. One example of this is the often-cited estimates compiled by the London-based advocacy organization Minority Rights Group. According to these figures, the total Romani population in Europe amounts to at least six million people, with large concentrations in Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Hungary, Albania, and the Czech Republic (Liégeois and Gheorghe 1995). Table 1.1 is based on the Minority Rights Group estimates compiled by Jean-Pierre Liégeois and Nicolae Gheorghe, and presents the percentages and absolute figures for the ten countries with the largest proportion of Romani citizens. Presented thus, the figures appear to suggest that there is complete clarity about the size and boundaries of the Romani population. This is quite misleading. When one reads further through the literature, one comes across figures that differ substantially from those offered by Liégeois and Gheorghe. Three areas of disagreement are apparent.

Table 1.1 Estimated Romani populations in Europe (percentages and absolute figures). The ten countries with the largest Romani populations in percentages.

Sources: Romani population figures are averages of the estimates in Liégeois and Gheorghe (1995: 7). Total population estimates come from the World Bank Data Profiles available at http://www.worldbank.org/data/countrydata/countrydata.html (2002).

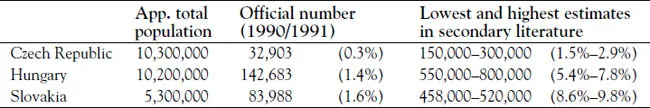

First of all, there are huge differences between estimated and official census figures. According to the Bulgarian anthropologists Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, the minimum number of Roma for the whole of the Central and Eastern European region (thus excluding Western European countries) is, based on censuses, about 1.5 million; while the maximum estimate, if one includes those of Romani activists, is around 6.3 million (Marushiakova and Popov 2001a: 34). Indeed, for the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia, one sees a large gulf between the official census figures and the available estimates (see Table 1.2).

Secondly, among the estimated figures themselves there is no clear consensus either. In fact, every new source seems to bring forth new figures, with sometimes spectacular differences in both percentages and in absolute figures (again, see Table 1.2).

And thirdly, there is also a striking variation among the available official census figures over the years (see Table 1.3). Despite the fact that estimates indicate a continuing growth of the Romani population over the last decades, official census figures have increased only slightly or have even decreased (again, see Table 1.3). The Czech case has been the most surprising example of this. The figure given in the census held in the beginning of the 1990s was regarded as manifestly too low by virtually all of the observers and activists to whom I spoke in the Czech Republic. However, the long-awaited 2001 census yielded an even lower result of only roughly one-third of the previous official figure. The census figure dropped to 0.1 percent of the population, notwithstanding that census forms had been made available in the Romani language. The most recent census figures in Slovakia and Hungary indicate the modest beginning of an opposite trend. However, the increases in the number of Roma were well below the expectations of many Romani activists in both countries.4

Table 1.2 Official and estimated Romani population figures in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia in the 1990s.

Sources: Total population estimates come from the World Bank Data Profiles (2002) available at http://www.worldbank.org/data/countrydata/countrydata.html. Official total Rom...