![]()

— Chapter 1 —

A REMOTE PLACE FROM THREE ANGLES

In the 43rd year of the reign of the Kangxi emperor (1704 CE), the poet and playwright Gu Cai embarks on a long journey into the mountains west of Yichang. He carries letters of invitation from his friend Kong Shangren, to visit Xiang Shunnian, the head of the chieftainship Rongmei. These chieftainships (tusi) do not have a Mandarin administration like the rest of the Empire, their populations speak languages partly incomprehensible to Chinese-speakers from the plains, and their rulers often cannot read and write Chinese. But the rulers of Rongmei and the other chieftainships in the region have been vassals to the emperor for centuries, and they have strong ties with officials and literati in the plains. Xiang Shunnian in particular is known to be a cultivated man who encourages and sponsors poetry, theatre and music at his court in Rongmei.

With the adversities of the weather, the mountain paths through endless woods, and the dangers of bandits and beasts of prey, it takes almost a month to reach Rongmei after leaving Yichang, the last town in the plains. Gu Cai carries with him the most recent play written by his friend Kong Shangren, entitled The Peach Blossom Fan (Taohua Shan, 1993 [1702]).1 After Gu Cai’s arrival in Rongmei, Xiang Shunnian has the play rehearsed and staged at his court in Rongmei. Together they spend a pleasant three months at the court in Rongmei, with many evenings of conversation, music, and poetry.

After his return, Gu Cai wrote down in verses what he had experienced in the mountains. Entitled Travel Notes from Rongmei (Rongmei Jiyou, 1991 [1704]), he left behind his lyrical elaborations for posterity. The Travel Notes are a poetic compliment to this area and his host Xiang Shunnian. Exchanging complimentary compositions and poems was one of the distinguishing marks of the empire’s scholar-officials, and Gu Cai’s Travel Notes bear witness that the chief (tusi) Xiang Shunnian was accepted by the literati as a peer. The book is full of poems about the landscape and the people of Rongmei. Setting the stage for the entire book, the first page contains a long comparison of the Rongmei chieftainship with ‘the peach blossom land’ (taohuayuan) of a well-known Chinese legend: a beautiful land that is far away in the mountains, where people remained honest and simple, and untouched by the oppression and chaos of the valleys.2

But Gu Cai also writes in his Notes about the more prosaic and miserable aspects of life in the Wuling mountains, the inaccessibility, the adversities of nature, the constant danger of bandits, and the poverty and misery of the peasants. In the history of the region there has been certainly much disorder, both political and social, as in many other regions of central China. But compared to the plains along the Long River in Hubei and also to the Sichuan plateau, the mountains of Enshi prefecture in Southwestern Hubei have had much less contact with the outside world. This is an outpost of the mountain regions of western Hunan, of Guizhou and Yunnan, where many people with languages and customs completely different to the Han Chinese were living. Compared with them, this area was much closer to the empire. Yet it is still ‘remote’ enough to be compared to the ‘peach blossom land’ of the legend. Even today people sometimes use the expression to describe the mountains of Enshi.3

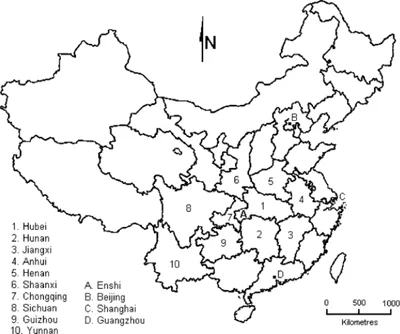

Map 1.1 Enshi, Hubei, neighbouring provinces, and major cities

The reminiscences of Gu Cai set the stage for the topics to be explored in this chapter: the image of a remote region as an idyllic and romantic place, sometimes utopian in its beauty, and disconnected from the demands and oppression of a civilizational centre; sometimes wild and dangerous, a jungle where ‘natives’ live maintaining martial traditions, and possibly rather unrestricted sexual conventions; and sometimes just images of backwardness and ignorance.

In what follows I will trace three discursive frameworks around different centres and what is remote to them, and by doing so, situate the place of my ethnography historically and spatially. The first two frameworks are the hegemonic discourses in which this remote mountain region is described in late imperial China, and now. Both of these are relatively far away and removed from the experiences of ordinary local people. The third one is the framework of families and lineages, and here people are actively living in a time and dwelling in a place that is not envisaged in the hegemonic discourses. In local tourism, lineage practice, and geomancy, such local practice enters partly convergent and partly conflictive relationships with hegemonic discourses.

The Enshi region of Southwestern Hubei Province lies in the Wuling Mountains, which stretch over north-western Hubei province, the south-eastern corner of Sichuan province (Chongqing), and along the border of Guizhou and Hunan provinces. On a map of the People’s Republic of China, it looks as if this region is right in the middle of the country (see map 1.1 and 1.2). In fact nowadays this area is thoroughly integrated into the political system of mainland China, and cultural and social differences between its inhabitants and the Han Chinese of Sichuan or Hubei are not obvious. Yet this is now a ‘Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture’ (tujiazu miaozu zizhi zhou), i.e. a minority district receiving a particular treatment within the political hierarchy. As a relatively inaccessible mountain region, this area shares many characteristics with the other borderlands of the Chinese empire in the south. Throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, the populations of these borderlands lived in constant exchange with the Chinese empire: sometimes in vassalage, sometimes in revolt, but altogether relatively independent. Many of these regions were eventually populated with Han settlers in the eighteenth century, when the Qing Empire reached its widest expansion.

Map 1.2 Hubei Province

When Gu Cai visited Rongmei, the area was predominantly governed by local chiefdoms (tusi), which were related in a particular vassal system to the Chinese empire. The Rongmei chiefdom was then one of the most prosperous and Gu Cai’s reminiscences show how learned and highly cultured the people at the court of its chief Xiang Shunnian were. The only place that was then governed directly by the Mandarins of the empire was the town of Shinanfu, which later became the capital with the same name as the prefecture: Enshi.

This vassal system of governance ended in the 12th year of the reign of emperor Yongzheng (i.e. 1735 CE), with a reform that ‘did away with the vassal chiefdoms and instead installed officials sent by the imperial court’ (gai tu gui liu).4 At the same time Chinese merchants and officials had started to promote and distribute two New World crops that had come mainly from the Portuguese and Spanish trading in the seaports of southern China: potato and corn. Originating from the highlands of South America, these crops proved to be particularly apt to the highlands of southern China, and played a major factor in the migration and ‘colonization’ of many new areas in south-western China.

During this same period, almost a million people left the plains of Jiangxi and Huguang5 in two huge waves of migration and went to Sichuan and Guizhou.6 Many immigrants followed the Yangzi upstream; some of them stopped at the ports of Yichang and Badong, and entered the mountains of what is now Enshi prefecture. A second group of immigrants was escaping from army conscription and floods in western Hunan and northern Guizhou and came to take advantage of the new possibilities of the vast land in the Wuling mountains that had hitherto been jungle. These population movements were partly promoted and guided by mandarin officials; the message spread amongst the settlers that they could take as much land as they could till up in the mountains, with only ‘the horizon in front of their eyes as a frontier’ (yi muguang wei xian). That, at least, is what is still transmitted in family histories and legends. The majority of families that are now living in Enshi prefecture can trace their ancestry back to one of these waves of immigration. In Bashan township, for example, there was a large group of immigrants from Jiangxi that had a common temple and a Jiangxi assembly (jiangxi laoxianghui) at the market town. This group probably took part in the first wave of migration. The second wave of migration also affected Bashan: many families still retell family legends and genealogies in which the origin of their families is traced back to places in Hunan and Guizhou (the most frequent places of origin of the families in Bashan are Baoding and Anhua, two small towns at the border of Hunan and Guizhou provinces). These legends and genealogies will be part of my third angle, described below. But first let us look at how the mandarins of the time described this mountain region.

Angle 1: Local Gazetteers

Whereas relatively few written sources about this region exist from earlier times, at the beginning of the eighteenth century the number of such sources increased rapidly. The majority of these are reports written by visitors and local gazetteers produced by the scholar-administrators of the region.

In imperial China, the mandarin administrators had to compile at regular intervals local gazetteers (difang zhi) of every county in the empire, including a basic census, customs, geographical conditions, flora and fauna, transport, local history, virtuous elders and widows, maps of the capital city and its official buildings, imperial posts, legends etc. Different in scope and content, such local gazetteers sometimes included veritable ethnographies. In the following I will cite some of the local gazetteers of Enshi County and the neighbouring regions compiled during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911 CE).

In most of these texts several features of the native ‘highlanders’ are continuously emphasized. One of the most commonly used words to characterize such mountain dwellers and their habits in these gazetteers is chunpu, which can be translated as ‘simple’ or ‘unsophisticated’. Generally it is used as a positive attribute, implying that someone is ‘honest’ and ‘upright’. Yet good nature and honesty could easily turn into naivety, and even unruliness and savageness. Indeed the martial characteristics and the unorthodox religious and sexual conventions of these people are frequently emphasized:

All the relevant local gazetteers compiled before 1949 say that the highlanders were given to believe in gods and spirits, often different from those worshiped by townsmen. They also say that these highlanders were extremely frugal, straightforward, physically strong (both sexes), arrogant, and quarrelsome. The compilers, urban scholars themselves, took a disapproving view of these strange, unruly attitudes and behaviour, particularly the highlanders’ sexual libertinism and their litigiousness. People of this breed were prone to protest and revolt. Their history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is indeed frequently punctuated by insurrections. (Ch’en 1992: 31)

In fact, such a description is by no means exceptional, or peculiar to peripheral regions. There are numerous similar texts about Han Chinese in many regions of China, showing the unease of the Mandarins at the superstitious beliefs, heterodox cults,7 sexual licence,8 and litigiousness9 of ordinary people. The content of the local gazetteers must be considered against their social background: their authors were scholar-officials within the hierarchies of the imperial bureaucracy. Thus the gazetteers were primarily intended for registering information that was necessary and useful for the administration, including geography, censuses, and the economic and political situation. Therefore, the gazetteers frequently read like handbooks for the mandarin administrators. But the central concern of the scholar-administrators was not just the facts about the regions, but how the morals and governance within the empire might be influenced. Unlike other forms of governance, the administration of imperial China was based much more on moral example than on factual control and command chains – and hence moral commentary and judgement was most important when dealing with peripheral people.10

At the same time, the authors were often writing about the districts where they themselves had some responsibility, and so they would sometimes try to embellish the situation. The most important benchmark of ‘civilization’ in imperial China was the level of Confucian learning. Hence one often finds phrases which emphasize the extent to which the local population was dedicated to learning, and how many excellent scholars came from this region, despite the extremely low probability of this in poor mountain areas. The following passage is an example of such achievements against all odds:

Enshi is located in the middle of thousands of mountains, and it cannot be reached on boat or carriage. The people there are very honest and sincere, and the customs simple and upright. The practice of learning and studying is wide-spread and well-established, and the people are not afraid of the effort and costs it implies. The gentry and the officials understand that good reputation and moral principles are the highest values and they judge each other by it. There are few thieves, and simple-minded bandits are afraid of the law. There is a lot of production in agriculture and handcrafts, which is sold for just market prices. […] Even though agriculture and living conditions are hard, people live happily to old age here. (Enshi County 1982 [1868]: 285)

Obviously, such a eulogy is full of set phrases, politeness, and circumlocution. In a sense, the mandarin officials could hardly write in any other way, because if they had pointed out all the difficulties of the region under their own administration, including poverty, immorality, and ignorance, surely higher officials would feel compelled to take measures.

Yet at some point it became necessary to indicate the negative side and the potential dangers of the mountain populations. Rather than being presented as factual statements about contemporary problems, such issues were more often cast in a historical narrative, hinting that such barbarity and savageness had since become civilized.

The local gazetteer of Enshi compiled in 1868, for example, contains an interesting piece about the ‘three transformations of local customs in Enshi’ (en yi fengsu san bian shuo; Enshi County 1982 [1868]: 291–292). It describes how during the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, the local population oscillated three times from relatively ‘simple’ and ‘honest’ (pu) customs towards ‘sophistication’ (hua) and then fel...