eBook - ePub

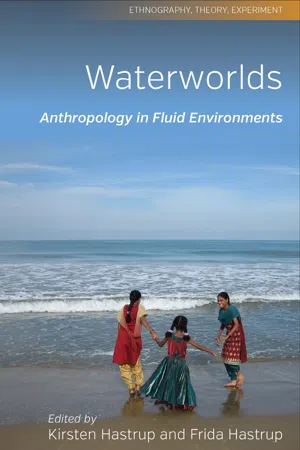

Waterworlds

Anthropology in Fluid Environments

- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Waterworlds

Anthropology in Fluid Environments

About this book

In one form or another, water participates in the making and unmaking of people's lives, practices, and stories. Contributors' detailed ethnographic work analyzes the union and mutual shaping of water and social lives. This volume discusses current ecological disturbances and engages in a world where unbounded relationalities and unsettled frames of orientation mark the lives of all, anthropologists included. Water emerges as a fluid object in more senses than one, challenging anthropologists to foreground the mutable character of their objects of study and to responsibly engage with the generative role of cultural analysis.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

East Anglian Fenland

Water, the Work of Imagination, and the Creation of Value

Richard D.G. Irvine

Of Wet and Dry Landscapes

But what is a fen? Is it not a wetland, defined first and foremost by its waterlogged nature? Borrowing liberally from Motley’s (1855) description of the lowlands of Holland and Belgium, Wheeler (1868: 3) characterizes the fens of East Anglia as historically consisting of ‘wide morasses, in which oozy islands were interspersed among lagoons and shallows, a district partly below the level of the tides and subject to constant overflow from the rivers, and to frequent inundations from the sea’. This is a liquid, not a solid, description; even the islands ooze.

A common ecological definition is that a fen is a groundwater-fed wetland (Bedford and Godwin 2003) (as opposed to a bog, which is precipitation fed), though more specific definitions have focused on the chemical characteristics of the wetland, such as the suggestion made by Wheeler and Proctor (2000: 197) of a pH level cut-off point, with fen defined as a mire (that is to say, peat-forming wetland) with a pH value greater than 5.5. All the same, Wheeler and Proctor (ibid.: 188–89) recognize that such typologies are at the tail end of a long etymological history (see Haslam 2003: 2–7, for an extensive inventory of popular and scientific usages), and from the point of view of thinking about the human experience of the landscape (or waterscape), it becomes very tricky to disentangle ecological terminologies from local uses of the term ‘fen’.

The East Anglian fenlands present a particular challenge to waterbound definitions. What is the fenland today? It is a flat, open, low-lying landscape, dedicated largely to arable farming. The exposed peat soil, when it is visible, is a vivid black. The land is level and apparently featureless – so level and featureless, in fact, that in the nineteenth century the landscape inspired Samuel Rowbotham’s observational experiments (carried out on the Old Bedford River, a fenland drainage channel) designed to prove that the planet Earth was, indeed, flat (Rowbotham 1865). There are very few protrusions in the land, and with no apparent landmarks to capture the eye, the fields seem to stretch into the distance as far as the horizon. With so little in the way of raised contours or tree cover to break the wind, you feel exposed to the elements as you move across the land. At dry times of year, the wind picks up the peat surface soil, carrying it away in dark, thick, clouds – a phenomenon known locally as ‘fen blow’. Today’s fen, then, does not lend itself to liquid description, but is characterized by the drier properties of the land as arable farm; properties that arise from its past qualities as wetland, but which in the present require the absence of water. This absence is, as we shall see, the product of tremendous labour. We are talking about a wetland from which water has been excluded – drained, channelled, diverted, managed, though never fully banished.

The goal of this chapter is to trace this (partial) exclusion of water. More specifically, I will write about the disputes that surround this exclusion; this is an ethnography of fen as a contested landscape, where water’s presence or absence (both real and imagined) shapes arguments over the region’s identity, use, purpose and future. To this end, I will tell stories of three episodes of change and contestation: the politics of East Anglian drainage works during the mid seventeenth century; the militaristic struggle against water in the Fenland during the Second World War; and contemporary efforts to ‘re-wet’ swathes of the landscape.

Civilizing the Swamp: Seventeenth-Century Drainage

Human attempts to impose some control over fenland water flow have a long history. Roman drainage and navigation channels had a transformative impact on the geography of some areas of the fens (Rippon 1999), and these Roman waterways continue to be visible, and in many cases usable, to this day (as will become apparent in the case studies I present later in this chapter). Following the Roman period, monastic houses were at the forefront of attempts to embank waterways and dig ditches, allowing additional drainage of land to increase yields on their estates (Darby 1940; Sayer 2009); difficulties encountered following the dissolution of the monasteries indicate the significance of their role in fenland drainage (Darby 1956: 5–11).

Given this longer history, why start an account of the drainage of the fens in the Early Modern period? Certainly, academic accounts, presentations in museums, local histories and narratives all refer to seventeenth-century drainage as the drainage of the fens. The definite article is misleading on a number of scores; not only does it exclude these earlier drainage efforts, it also obscures the fact that much of the work of drainage during the seventeenth century met with mixed success (as we shall see), and the visible landscape of the fens today owes a great deal to nineteenth- and twentieth-century drainage efforts. This is not, however, to belittle the importance of seventeenth-century drainage.

Such drainage was a major undertaking of venture capitalism; indeed, this is reflected in the fact that the term used for the investors in such drainage was ‘Adventurers’. In 1631, thirteen of these Adventurers, mostly already landowners in the region, joined together under the leadership of Francis Russell, the Fourth Earl of Bedford, to form The Bedford Level Corporation. Each owned one or two shares in the corporation, with each share dependent on an initial investment of £500, to be used towards the drainage works. In return for this initial investment, each Adventurer was promised private ownership of four thousand acres of land per share. Their contract received the approval of King Charles I, who in return expected his own twelve thousand acres allotment of land. What is clear from this project, the largest and surely most significant drainage initiative at this time in England, is not only the enormous scope of its ambition, but also the economic and ecological impact of such an endeavour, transforming an enormous portion of peat wetland into drained land for agricultural purposes, and granting rights of private ownership over large portions of land that were previously designated as common (see Wells 1830 for a detailed historical account produced for the corporation itself; see also Darby 1956 for a comprehensive account of the economic history of drainage). Under the direction of the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden (see Harris 1953 for an account of Vermuyden’s role), the corporation commenced the embankment of existing rivers, and the cutting of enormous channels to improve drainage and allow for more direct outfall to the North Sea, ranging in distance from two to twenty-one miles.

So this was a programmatic attempt to change what the fen was; to make a wet land a dry land (to a limited extent, at least; the first scheme still anticipated some seasonal flooding). But alongside the technical accomplishment of changing patterns of water flow, we must also consider the significance of the work of this period in changing the way people think about the fen and what it is. The fenland becomes a source of potential wealth, but only if the water can be excluded. It is, in this sense, a land of imagination. The petroleum geologist and oil company director Wallace Pratt, in his paper ‘Toward a Philosophy of Oil-Finding’ wrote:

Where oil is first found, in the final analysis, is in the minds of men. The undiscovered oil field exists only as an idea in the mind of some oil-finder. When no man any longer believes more oil is left to be found, no more oil fields will be discovered, but so long as a single oil-finder remains with a mental vision of a new oil field to cherish, along with freedom and incentive to explore, just so long new oil fields may continue to be discovered. (Pratt 1952: 2236)

This remark has tremendous resonance as an illustration of the mindset of the ‘Adventurer’. The quest to find new resources requires imagination: oil finding is not just about capital investment and technical expertise, but the vision that recognizes the potential to find wealth in places where that wealth had not previously been imagined. So too for the creation of new agricultural land and the ‘black gold’ of fenland peat soil (to adopt the term commonly used by today’s fenland farmers). The creation of a new kind of agricultural land on this scale is first and foremost a discovery ‘in the minds of men’.

The work of drainage is the work of imagination. A major drainage scheme of this sort requires the fens to be treated as a kind of terra nullius, indeed, as a blank space onto which desires can be projected. The Adventurers must imagine and re-imagine the fens: first, imagining them as a void; then, re-imagining them through the projection of a promised land onto this void. This is made quite apparent by the establishment of a parallel between the work of drainage and God’s work of creation out of the void – William Dugdale, author of a History of Imbanking and Drayning commissioned by Lord Edward Gorges, an Adventurer with the Bedford Level Corporation, begins his account in this way: ‘That works of Drayning are most antient and of divine institution, we have the testimony of Holy Scripture. In the beginning God said, let the waters be gathered together…’ (Dugdale 1662: 1).

Dugdale’s method of representation is instructive: we are left in no doubt that the pre-drainage fens are a chaotic space, where the elements themselves are disordered. ‘What expectation of health can there be to the bodies of men, where there is no element of good? The Air being for the most part cloudy, gross, and full of rotten harrs; the Water putrid and muddy, yea full of loathsome vermin; the Earth spungy and boggy; and the Fire noisome by the stink of smoaky hassocks’ (Dugdale 1662: 7). This is a depiction of fen as somehow before time, before civilization. As McLean (2007, 2011) has noted in his reflections on European peat bogs and fens, these swampy margins often come to be represented as a prehistoric unknown, untamed. It is ‘black primordial goo’ (2007: 61). Little wonder, then, that progress declares war on the swamp. McLean (2011: 602–3) gives an account of Mussolini’s ill-fated Utopian resettlement of more than sixty thousand people on reclaimed land on the Pontine Marshes, while poets and artists – such as those McLean (2007) met in a sculptor’s symposium in County Wicklow, Ireland – peer into the mud as though it were a window into the past and ask themselves what is down there. Pre-drainage fen is primitive; it is exactly this sense that we get from reading Dugdale. And being primitive, it is surely no good.

By contrast, drained fen is land that is ‘improved’, and the work is commended as a plan to ‘enrich these countries by several new plantations, and divers ample privileges’ (Dugdale 1662: 414). Given that Dugdale was writing to a commission, we might think of him as the producer of paid propaganda, but he was by no means alone in his vision of the creative power of drainage. Keegan (2008: 151–59) provides something of an inventory of poetry written in praise of the work of the Adventurers; she quotes, for example, a poem attributed to Samuel Fortrey, and found in another historical narrative of drainage published by Jonas Moore, surveyor for the Adventurers (Moore 1685):

I sing of Flood muzled, and the Ocean tam’d,

Luxurious Rivers govern’d, and reclam’d,

Waters with Banks confin’d, as in a Gaol,

Till kinder Sluices let them go on Bail;

Streams curb’d with Dammes like Bridles, taught t’obey

And run as strait, as if they saw their way.

In place of chaos, order; and in place of flood, progress. The result is envisioned as a fertile paradise of plenty: ‘The Land of Promise, now in part enjoy’.

In this task of imagining the transformation of the fens, the work of projecting a ‘before’ and ‘after’ onto the apparent blank canvas of the fenland made ample use of the power of maps. As Willmoth (1998) has pointed out, in preparing his History of Imbanking and Drayning Dugdale sought sponsorship for the production of engraved plates, allowing the end result to be lavishly illustrated. Such illustration not only created the appearance that this was a work of antiquarian importance to be placed on a level with Dugdale’s work on more conventional historical subjects, such as his history of English abbeys, Monasticon Anglicanum, but also ensured that the story of creation of land from waste had the maximum visual impact. Dugdale included within the volume a ‘Mapp of the Great Level; Representing it as it lay Drowned’; here, it appears, Dugdale took a map that had been produced by William Hayward earlier in the century and, through shading those areas subject to flooding, created an image of the fens as a vast sea, so that ‘the flooded state of the Fens appeared almost their sole characteristic’ (Willmoth 1998: 283). Here, he was adopting a strategy used by other mapmakers of the time; in 1645 the Dutch mapmaker Joannes Blaeu also produced a similar map based on William Hayward’s earlier map of the fens; ‘Heavy shading was added to make the whole central area appear under water, and the new title, Regiones Inundatae – “flooded regions” – makes the propagandist nature of this particular enterprise very clear’ (Willmoth 2009: 15). In this way, the fens could be simplified in their entirety as a wild, flooded zone, awaiting civilization. Maps of the fens after drainage, by contrast, imply a neat grid pattern of drainage ditches and allotted agricultural land. Jonas Moore’s map of the Great Level, produced in 1658 and redrawn for inclusion in Dugdale’s History, ‘is an extremely impressive production, at a scale of about two inches to a mile. It has some of the characteristics we might now associate with an aerial survey, although it depicts an area where no kind of bird’s-eye view could in practice be obtained’ (Willmoth 2009: 18). Looking down on the fenlands from above, we see the achievement of the drainage as nobody on the ground could have seen it; as a perfectly ordered design.

What is perhaps most striking about seventeenth-century accounts of drainage, and what still clearly has a resonance to this day, is that the works are framed as a moral project. We have already seen Dugdale’s claim that pre-drainage, the fen contained ‘no element of good’ (1662: 7); later he describes the land and its inhabitants thus: ‘until of late years, a vast deep fen, affording little benefit to the realm, other than fish or fowl, with overmuch harbour to a rude, and almost barbarous sort of lazy beggarly people’ (Dugdale 1662: 171). It is noteworthy than the inhabitants of the fen were singled out as lazy; indeed, sloth comes to be seen as a characteristic of the fenland environment itself, and drainage a remedy to this natural laziness: ‘the river Ouse, formerly lazily loitering in its idle intercourses with other rivers, is now sent the nearest way (through a passage cut by admirable art) to do its errand to the German Ocean’ (Fuller [1655] 1840: 149). The ‘improvement’ of the fens, then, is a project that replaces laziness with industry, to the benefit of land and people; to return to Samuel Fortrey’s poem in Jonas Moore’s narrative of drainage:

When with the change of Elements, suddenly

There shall a change of men and Manners be;

Hearts, thick and tough as Hydes, shall feel Remorse,

And Souls of Sedge shall understand Discourse,

New hands shall learn to Work, forget to Steal,

New legs shall go to Church, new knees shall kneel.

Clearly this is not just a work of improvement; it is an inscription of the Protestant Work Ethic on the land and on the people. The Earth is given to humans for their use; ‘labour in the service of impersonal social usefulness furthers the divine glory and is willed by God’ (Weber 1930: 76) – and to waste land given by God through failing to add labour is surely a sign of immorality.

This moral justification for the project of the Adventurers rests on the idea that the fens were waste. Such an idea was to become central to the philosophy of property of Locke: ‘Let anyone consider, what the difference is between an Acre of Land planted with Tobacco, or sugar, sown with Wheat or Barley; and an acre of the same land lying in common, without any husbandry upon it’ (Locke [1689] 1960: 296). In this way, Locke makes the case for the creation of property in land. To add labour to land is to make it productive; and when the individual, who is proprietor of himself, mixes his labour with a resource in the commons, as is necessary for survival, it becomes his property. Were he not to do this, it would surely go to waste. Here, we see the same rationality that was put to work in the Adventurer’s drainage of the East Anglian fens; adding the labour of drainage to the ‘waste’ of a wetland in order to make it productive, and in doing so creating private property. Later, Locke makes his point even more starkly: ‘Land that is left wholly to Nature, that hath no improvement of pasturage, Tillage, or Planting is called, as indeed it is, wast’ (ibid.: 297).

Locke attempts to drive his argument about the importance of labour and private property home with a contrast. ‘There cannot be a clearer demonstration of anything, than several nations of the Americans who are rich in land and poor in all the Comforts of Life; whom nature having furnished as liberally as any other people, with the materials of plenty … yet for want of improving it by labour, have not one hundredth part of the conveniences we enjoy’ (Locke [1689] 1960: 296–97). With this parallel in mind, the drainage of the fens becomes a kind of internal colonialism (Ev...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction. Waterworlds at Large

- Chapter 1. East Anglian Fenland: Water, the Work of Imagination, and the Creation of Value

- Chapter 2. Fluid Entitlements: Constructing and Contesting Water Allocations in Burkina Faso, West Africa

- Chapter 3. Raining in the Andes: Disrupted Seasonal and Hydrological Cycles

- Chapter 4. Respect and Passion in a Lagoon in the South Pacific

- Chapter 5. West African Waterworlds: Narratives of Absence versus Narratives of Excess

- Chapter 6. To the Lighthouse: Making a Liveable World by the Bay of Bengal

- Chapter 7. Enacting Groundwaters in Tarawa, Kiribati: Searching for Facts and Articulating Concerns

- Chapter 8. Mapping Urban Waters: Grounds and Figures on an Ethnographic Water Path

- Chapter 9. Water Literacy in the Sahel: Understanding Rain and Groundwater

- Chapter 10. Deep Time and Shallow Waters: Configurations of an Irrigation Channel in the Andes

- Chapter 11. Moral Valves and Fluid Properties: Water Regulation Mechanisms in the Bâdia of South-Eastern Mauritania

- Chapter 12. Reflecting Nature: Water Beings in History and Imagination

- Chapter 13. The North Water: Life on the Ice Edge in the High Arctic

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Waterworlds by Kirsten Hastrup, Frida Hastrup, Kirsten Hastrup,Frida Hastrup in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.