eBook - ePub

The Good Holiday

Development, Tourism and the Politics of Benevolence in Mozambique

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Good Holiday

Development, Tourism and the Politics of Benevolence in Mozambique

About this book

Drawing on ethnographic research in the village of Canhane, which is host to the first community tourism project in Mozambique, The Good Holiday explores the confluence of two powerful industries: tourism and development, and explains when, how and why tourism becomes development and development, tourism. The volume further explores the social and material consequences of this merging, presenting the confluence of tourism and development as a major vehicle for the exercise of ethics, and non-state governance in contemporary life.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introducing Tourism

Canhane

At the beginning of 2001, the Swiss director of the NGO Helvetas in Maputo went to the city of Nelspruit in South Africa. Nelspruit is commonly used by the new postcolonial elites living in the capital of Mozambique as a place to escape to. The cities are connected by nearly 200 kilometres of prime asphalt. In Nelspruit, the abundance of shiny shopping centres and offices of international organizations in the downtown area is the main attribute that captivates, in particular, the expatriates living in southern Mozambique.

While there, the Helvetas director consulted the periodic South African journal of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The journal included a discreet announcement of the awarding of grants for so-called community development in the surrounding region of the Limpopo National Park in southwest Mozambique. ‘The content of USAID’s announcement was very generic. It only mentioned the area of implementation – a vast area, though’, one of the staff working for Helvetas confirmed to me in September 2006.

Soon after the Swiss director returned to Maputo, he urged an internal working group to prepare an application for the funds. ‘He came back from Nelspruit very awakened,’ a security guard at the Helvetas offices recalled. The enthusiasm that radiated from him was prompted by more than just the possibility of new funds for the NGO. The Swiss director saw an opening to a world of opportunities for Helvetas if they succeeded with their application. As I became aware through the numerous conversations I had with the NGO professionals in 2008, USAID’s announcement meant an incentive for the NGO to extend its work, its authority and the ethos of community development into southwest Mozambique.

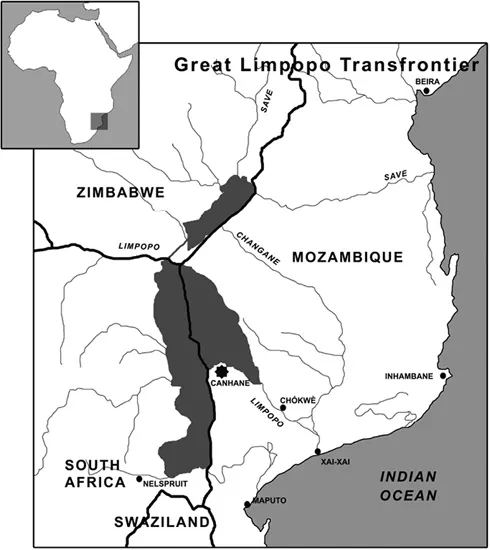

The targeted region has a special character. It lies in the buffer zone of a transfrontier conservation area named Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park (GLTP). This is a zone which in the last decades has been projected and considered, at least politically, in a transnational fashion.1 It was officially proclaimed a conservation area on 10 November 2000 by the Ministers of the Environment of three neighbouring countries: South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. They signed a document authorizing the incorporation of South African’s Kruger National Park, Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park and Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park into one single transfrontier conservation area of approximately 35,000 square kilometres. According to the official information provided by the park, ‘The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park will be a world-class eco-tourism destination … managed to optimize benefits for sustainable economic development of local communities and biodiversity conservation’ (Hohl et al. 2015: 46).

The GLTP was initially launched in the 1990s through Anton Rupert’s personal initiative. Rupert2 was a wealthy South African philanthropist, conservationist and tobacco magnate whose multiple business ventures included tourism. He was a founding member and the former president of World Wildlife Fund (WWF) South Africa (then called the Southern African Nature Foundation). It was Rupert who initiated talks with the Mozambican government and involved the World Bank in the conservation border initiative. During this lobbying process, the region gained the status of possibility, a horizon of ecological and social potential to be realized under the auspices of development and tourism. The envisioned future of a transnational geography that appeared to embody morality persuaded various international institutions and corporations to financially support the GLTP initiative.3 The USAID announcement that captivated the Swiss director in Maputo was part of this trend.

Officially, the GLTP is rooted in a field of benevolence ‘beyond boundaries’ (Spierenburg, Steenkamp and Wels 2008: 87). On the surface, it was born and operates under the aura of ecological concern and general goodwill. This is revealed through the formal rhetoric that accompanies it, namely the ‘promotion of cooperation and peaceful relations between member countries’ (Lunstrum 2013: 3). The institutional name of the park reinforces it: ‘Peace Park’. Accordingly, the most prominent ‘non-profit’ institution in charge of the GLTP describes the park in this way: ‘the establishment and development of [the GLTP] is … an African success story that will ensure peace, prosperity and stability for generations to come.’4 Furthermore, the association of the GLTP with (supposedly) universal qualities is conspicuous in public discourses and public events related to the park. For example, at a ceremony to celebrate the relocation of twenty-five elephants from South Africa to Mozambique in the GLTP, Nelson Mandela said, ‘I know of no political movement, no philosophy, no ideology, which does not agree with the peace parks concept as we see it going into fruition today. It is a concept that can be embraced by all.’5

For Louis D’Amore, the righteous character of the GLTP derives from an ideology ‘of peace [that is based on] the perspective of an organic and interconnected world’ (1994: 113). Indeed, the aura of virtue hovering over the park seems to stem from the promises that transnational integration, mobility and connectivity represent in the universal modern sensibility. In his extensive ethnography of the GLTP’s implementation, David Hughes participated in various workshops and meetings where, he says, ‘ecologists spoke repeatedly of the need for … “connectivity”’ (2005: 169), which they linked to a more virtuous ‘future government’ in the region (172).

All things considered, in this discourse of grace, promise and transnational circulation, tourism and the tourists emerge as the natural supporters and allies of the GLTP. And so, the industry of tourism becomes seen as an industry of peace and brotherhood in the region (Khamouna and Zeiger 1995: 86; Litvin 1998: 63). What had begun as a modest scheme for groups of smallholder farmers and herders to benefit from tourism (Hughes 2005: 158) has grown to become a mammoth landscape of leisure – a prodigious terrain of ecological union, freedom and mobility for all. Consider the message conveyed by Open Africa, one of the most active tourism companies in the GLTP, about the Park: ‘travelers, like animals, should march across Africa’ (Hughes 2005: 173).

Yet, to its critics, the version publically portrayed of the park – as a unifying and moral socio-green venture – camouflages its real goals. One of these critics is Rosaleen Duffy, who argues that the NGOs that take over transfrontier conservation ventures, such as the GLTP, ‘are part of a process of shifting responsibility for conservation out of state hands and into the hands of non-state entities and complex, non-territorial networks of governance’ (2006: 96). This is actually a criticism voiced by various Mozambican officials who worry that the assistance provided to the park by international technocrats and donors comes with strings attached, or with conditionalities that impinge upon the decision-making capacity of the national, regional and local government (Lunstrum 2013: 4). Other critics say that the park is fundamentally about the creation of new saleable products and about the integration of the region into the broader markets of development and tourism. Within this process, Spierenburg and colleagues warn, ‘local communities are … under-represented, under-respected, under-skilled and under-resourced actors in this power game’ (2008: 96). In regard to the growing importance of networks of NGOs and institutions in the area, Maano Ramutsindela (2007) argues that the relationship between the Peace Parks Foundation, which plays a key role in monitoring the GLTP, and the private sector represents the infiltration of global neo-liberal principles into the region. According to Ramutsindela, this is evident in the way that international corporate sponsors use their funding of the Peace Parks Foundation as a means to establish their brand in the marketplace. These corporations, he suggests, try to capitalize on the institutionalization of an ethic of ecological intervention in the region in order to enhance profits.

Figure 1.1. The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park (GLTP) and adjacent areas. Map by the author.

Indeed, many scholars have referred to the ways in which environmental conservation all over the world is utilized for profit by international organizations (Jamal and Stronza 2009: 315). Specifically, in the language of the GLTP planners, moral economy often seems to substitute for, or at least to intermix with, the ecological. To mention a few examples, Du Toit describes the park as ethically and economically optimal because wildlife held a ‘comparative economic advantage’ over cattle (du Toit 1998, in Hughes 2005: 171). In a presentation for an elite of conservationist technocrats, Rowan Martin, who is an influential consultant for development projects in southern Africa, presented his suggestions for the GLTP under the title: ‘The potential earnings from wildlife are limited only by marketing skills’ (Hughes 2005: 172). Continuing in this atmosphere of marketability, Hans Harri, a South African tourism magnate, referred to the GLTP as a ‘Limpopo tourism corridor’ that could boost investor-led growth. This is what he said about the park to one of Mozambique’s leading newspapers:

The entrepreneurial dynamic obliges the men who have big business in South Africa to look, in other parts of the globe, for other markets. This is dictated by development, and we are sure that, in addition to satisfying the ambitions of our businessmen, we will contribute so that, in record-time, a strong economy is implanted in your country [Mozambique] (Notícias 1997: 9, in Hughes 2005: 173).

This prophetic thinking has conjured a wave of transnational flows and interventions in and around the park. The GLTP’s scope has evolved from a Southern African story to become a significant conservation and tourism modality of transnational modern life to be told to the world at large. In the process, the Mozambican side of GLTP gained the quality of an economy of possibilities; a terrain promising futures to a myriad of agents, including international companies, development institutions and local populations: ‘an anticipated economy’, as Hughes (2005: 172) calls it. According to the scholar-consultant Anna Spenceley, the official Joint Management Plan of GLTP ‘encourages the park to work closely with the tourism industry … [and] recommends that cultural tourism be developed and marketed within local communities’ (2006b: 651–52). To be sure, human residents, natural scenery and fauna in and around the park gained the role of resources to further one end: tourism.

Joining in with this current, NGO Helvetas applied for USAID funds with a project aimed at ‘community development through tourism’. The idea was to establish a tourist lodge in the buffer zone of the park that would capitalize on its proximity to the GLTP. In turn, this lodge would provide benefits for the local community while also offering a cultural experience for international tourists. The proposal was opportune and morally sound. The applicants did not have to wait long to receive an affirmative response, and obtained an initial $50,000 in funding from USAID. In the successful project proposal, Helvetas did not specify the target area (or population) for the intervention. This became defined only after many consultations by the NGO’s staff in 2002 with provincial and district government representatives.

In one of these sessions, the district administrator of Massingir invited several professionals of the NGO Helvetas to visit a place he thought had potential. Located in the Municipality of Tihovene, the area had a scenic view over the Elephants River and the Limpopo National Park. The sensory potency of the landscape, the tranquillity of the locale and its aura of privacy, as one of the visitors explained to me, instantly captured the group’s attention. ‘And that was it,’ he said conclusively. ‘We all agreed about the place. We all saw its tourist potential.’ The visual impressiveness of the landscape played the decisive role in the selection of what came to be the location of the first community lodge in Mozambique. As Spenceley put it, no analysis ‘was undertaken by Helvetas to evaluate whether the lodge [in Canhane] was the most sustainable form of tourism development for the community’ (2006a: 23, emphasis added).

‘The Community’: Canhane

‘When we first arrived there, the community of Canhane didn’t know anything about tourism,’ the main precursor of the tourism project working for Helvetas said. ‘We asked them,’ he recalled, ‘“What do you guys from the community need most?” After we listened to their answers, we informed them about how tourism could be a good way to achieve that in the community.’ The following is an excerpt of an internal report made by Helvetas (2002a: 3, 6) on the first meeting they had with the residents in Canhane:

The meeting was held on the 05 November 2002, where 64 people participated, from the figure 31 were women and 33 men.

2.0 Objectives

• To know the Canhane community.

• Identify the natural resources and existing problems in the zone.

• Disseminate the land law and its regulation.

• Confirm the site of the tourist camp.

… After the presentation there was a space for discussion. In the first moment people were not sure what to say. After about 3 minutes answers were like as follow:

‘We want the tourism project to come as soon as possible, we do not want to wait for long period’ [sic] said one of the participants.

From this meeting onwards, three decisive concepts were brought by the NGO staff into the everyday life of Canhane: community, tourism, and community tourism. These concepts were translated into expressions of novelty, solution and hope, irremediably shaping the politics of the local from then on.

According to data from 2006 directly provided by the hereditary leading authority in the village – lider comunitário (community leader, in English), as the residents refer to him6 – Canhane has a population of 1,105 residents (567 women and 538 men), making up 203 families. Owing to the predominance of informal emigration to South Africa,7 particularly to work in the mines, those numbers are inaccurate. My guess is that not more than 650 people actually lived in the village in 2008, during my time there. Similarly to what Stephen Lubkemann (2000) describes from his research in the Machaze area of Mozambique, some men from the village established permanent households in both South Africa, where they work, and Canhane, their birthplace. The residents speak Shangane and only a few are fluent in Portuguese, the national language of Mozambique. All the people originally from the region are known as Machanganas, meaning ‘the people of Sochangana’, who, escaping from Shaka Zulo in 1821 in South Africa,8 conquered part of present-day Mozambique.

As soon as the population of Canhane accepted the tourism project, they had to reorganize internally in order to conform to external demands. The residents were asked to create a co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations, Figures, Tables and Diagrams

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Introducing Tourism: Canhane

- 2 The Appeal of Community

- 3 Developmentourism

- 4 The Enigma of Water

- 5 The Walk

- 6 Problematizing Poverty

- 7 Non-Governmental Governance

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Good Holiday by João Afonso Baptista in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.