![]()

Chapter 1

THE REVOLT OF THE MASSES

Populist Radicalism and the Discontents of Modernity

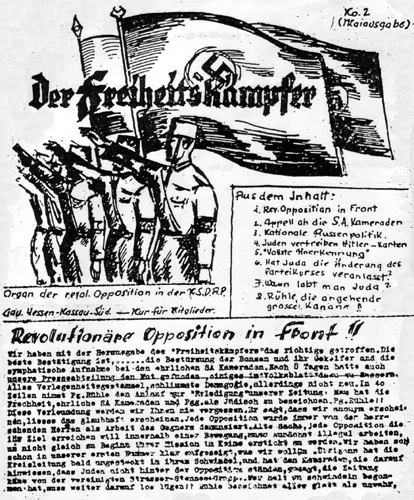

In June 1931, in the midst of Hitler’s drive to power in Germany, an official of the Nazi paramilitary wing (the Sturmabteilung or SA) wrote to party headquarters in Munich to report a worrying incident.1 A crude antiparty newspaper—Der Freiheitskämpfer (The Freedom Fighter)—had appeared in Düsseldorf. The product of a self-styled “Opposition” within the SA, this invective-laced sheet lambasted local party leaders for corruption and challenged the overall direction of the Nazi movement. The paper complained of the watering down of Nazism’s revolutionary goals, a charge it leveled in particular against Adolf Hitler.2 Such charges were not uncommon in a Nazi movement struggling to walk the tightrope between bourgeois respectability and revolutionary élan, even if critics usually stopped short of blaming the Führer himself; but particularly worrying in this case was that Der Freiheitskämpfer had been distributed in a local SA barracks by a uniformed Sturmführer (the equivalent of a platoon leader), the very rank responsible for overseeing the discipline and political reliability of the rank and file. The incident seemed to underline just how serious had become the rot within the SA, a formation that had played a major role establishing the presence of National Socialism on the political stage. Only a year previously, open rebellion had broken out in Berlin around the regional SA leader, Walther Stennes, and the rebel group led by Stennes and the former party leader Otto Strasser—a self-styled proponent of the “socialism” in National Socialism—continued to agitate and canvas for followers.3 The official took it for granted that Der Freiheitskämpfer was a product of the Stennes-Strasser group; but in arriving at the obvious conclusion, he failed to take account of the evidence presented in his own letter. The Sturmführer who distributed the paper, he wrote, had been seen afterward in the company of another SA man entering a Communist printing house. This proved, he wrote, that the man was a “scoundrel.” But there was something more at work, for the two stormtroopers were actually (in the parlance of the times) “Beefsteaks”—Nazis who were “brown on the outside and red on the inside.”4 Indeed, the Sturmführer—who, after being expelled from the SA as a result of this incident, became a star performer at Communist meetings organized to win over Nazi militants to Communism—was by no means the only Beefsteak at work in the SA, either before or after January 1933.5 But how did Communists come to join the Nazi stormtroopers? And how did the Communist Party of Germany (KPD)—a party that staked its very existence on its intransigent opposition to fascism—come to produce a “Nazi” newspaper complete with bloodthirsty rhetoric and anti-Semitic stereotypes?6

Figure 1.1 Der Freiheitskämpfer, no. 2, May 1931. NSDAP Hauptarchiv, Hoover Institution Microfilm Collection.

If Der Freiheitskämpfer were to appear in any of the existing works on the relationship between Nazism and Communism in the Weimar Republic, these questions would probably be answered as follows: the production of Zersetzungsschriften (subversion papers) and the activity of Communist agents in enemy uniform was but an extreme expression of the KPD’s effort to combat the growing influence of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in the latter years of the Weimar Republic.7 Carried out by a secret department within the party charged with undermining both the armed forces of the state and the mass paramilitary formations of the radical right, it was part of a broader campaign of subversion aimed at dissolving from within the organizational cohesiveness of Communism’s opponents.8 Characterized by semiotic trickery and deliberate blurring of ideological boundaries that mirrored similarities in ideology and tactics at the party level,9 this campaign was carried out in the context of a shared “culture of radicalism” between rank-and-file militants at the neighborhood level.10 This hypothetical analysis of Der Freiheitskämpfer’s significance would be correct as far as it goes—as we will see, such papers were indeed part of a Communist campaign of subversion.11 But in folding this most striking incident back into a narrative emphasizing the ideological and organizational coherence of “left” and “right,” such an analysis would risk closing down inquiry at precisely the point at which it should be opened up. For this artificially constructed point of convergence between the radical extremes—one that resonated, as we will see, with the suspicions, fears, or hopes of contemporaries—represents more than a piece of tactical ephemera in a clandestine struggle between two extremist movements; it offers us a challenging point of departure for a fresh appraisal of the radical politics of the Weimar Republic.

Der Freiheitskämpfer is a fictive intervention at the juncture of two competing radicalisms; but it is also a signpost pointing toward a little-known world of espionage and infiltration in which two mass movements watched, interacted with, and attempted to influence each other, right down to the individual level. The sphere within which it was produced, distributed, and received represents a concrete location of overlap between two extremist movements; the sources with which it is imbedded—the little-exploited files of the secret Communist spy apparatus that produced it, the reports of police and Nazi counterspies who observed it, the propaganda of rebel Nazis and other radical groups that competed against it—cast a new light on seldom-analyzed aspects of the relationship between Nazism and Communism. The idea of the Beefsteak—as both social myth and reality—is one of these, as is the phenomenon of “side-switching” between one party and the other.12 In this book’s final chapter, in particular, these sources—especially the little-exploited reports of Communist spies within the Nazi mass organizations—cast a new light on the process of Gleichschaltung (coordination) through which the Nazi regime consolidated its hold on power after 30 January 1933.

But sources such as Der Freiheitskämpfer function on a second level as well, for they represent the attempt of one extremist movement to perform the other, to quote, to mimic its opponent. In this respect they offer indirect evidence about rank-and-file Nazi ideology by suggesting what Communists—who, as recent scholarship has demonstrated, frequently lived in intimate physical and cultural proximity to their Nazi opponents—knew about Nazi grievances and motivations.13 They also tell us something about the Communist Party itself, for the attempt to divert rank-and-file Nazi radicalism in a class conscious direction can be seen as an extension of the practice of speaking in the voice of the masses that characterized the party’s relationship with workers in general.14 But the real importance of this mimetic element is that it suggests the way that in quoting each other, extremist movements played with a set of ideas and terms—“socialism,” “nationalism,” “revolution,” among others—that, whatever their differing valence from situation to situation, made up part of a discourse that extended across organizational boundaries and allowed radicals of differing stripes to talk to each other. The ideas and terms of this discourse, to which we will refer, after the contemporary social philosopher Helmuth Plessner, as a discourse of social radicalism, supplied the basis for a wide-ranging discussion about the nature of the ideal revolution and the ideal qualities of the revolutionary.15 It also supplied the basis for appeals, by turns emotive and rationalist, aimed at “enlightening” or converting opponents. This emphasis on argument, moral persuasion, and “conversion” is at least as important to our understanding of the relationship between the radical extremes in the Weimar Republic as the political violence that has so often been emphasized.16 One aim of this study, therefore, is to emphasize the importance of this many-sided conversation—a conversation that took place across the various National Socialist and Völkisch splinter groups; the individuals and grouplets of the “National Bolshevik” scene; the manifold formations of the youth movement—and to situate the relationship between Nazism and Communism as mass movements within it.17

This approach differs significantly from what has come before, not only in its empirical focus—it is one of the very few studies, since the work of Schüddekopf in the 1960s, to pay much attention to the interplay between the mass movements and the smaller groups around them, and the first to explore in any detail the KPD’s subversive work in and around the NSDAP—but in its theoretical and methodological approach.18 Whereas previous studies have emphasized the political history of the relationship between the two movements—largely through the lens of the KPD’s defensive response to insurgent Nazism—or examined radical culture in highly local and essentially social-historical terms, this study is concerned with culture in its performative aspect; that is, while acknowledging the concrete importance of factors such as class, gender, and generation (as they appear, for example, in the recent work of Pamela Swett), it is more concerned with the symbolic function of these qualities, not only in the formation of radical identities from below—that is, in the self-understanding of radicals—but also in the depiction of those identities from above. The study breaks new ground in examining how the two mass movements attempted to shape and direct the radicalism of their followers and in demonstrating how this shaping and directing was central, not only to the self-constitution of the two movements but also to their relationship with each other. It traces this struggle to shape and direct into the early years of the regime, when the multisided debate over the meaning of revolution continued, contributing to the revolutionary ferment that helped solidify the Nazi hold on power.

Both Nazism and Communism tried to embody a form of populist anti-authoritarianism, the former under the rubric of race and nation (embodied in the idea of the Volksgemeinschaft or “people’s community”), the latter under the rubric of class.19 At a purely formal level, these conceptions were diametrically opposed—one was nationalist, the other internationalist; one mystical-vitalist, the other materialist; one racist, the other universalist. In practice, however, these competing rubrics tended to lose their clear delineation and in places even to overlap, as Conan Fischer has demonstrated.20 This overlap occurred in particular, it will be argued here, where one movement tried to stage elements of the radicalism associated with the other—that is, in cases where (for example) the Nazis played with symbols and rhetoric of class (i.e., “working class-ness”), or where the Communists played with the symbolism and rhetoric of the nation.21 In doing so, both contributed to the discourse of social radicalism in which a range of ideas traditionally associated with “left” and “right” were in play. Characteristically, however—and here we come to a central contention of this study—the staging that movements attempted to enact for their own followers became entwined with the mimetic staging that they enacted for purposes of prosyletization or subversion of their competitor. In this light, the relationship between Communism and Nazism in the Weimar Republic becomes not simply a matter of two discrete mass organizations (two competing “totalitarianisms”) trying to outmuscle each other in a struggle for power, but a matter of the dovetailing of two sorts of staging—that within movements and that between movements.22

This approach requires a fresh way of looking at radical politics, one that can be usefully developed with the help of three spatial metaphors. The first of these involves looking at Nazism and Communism not as two movements occupying opposite ends of a political “spectrum,” but rather as two poles around which coalesce particular constellations of force. Such a scheme does not involve jettisoning the terms “left” and “right,” which retain a heuristic usefulness in capturing broad affective orientations—the former suggesting Marxism, workers, the primacy of class; the latter the authority, order, the primacy of nation—but it does entail recognizing these orientations to be contingent, nominal, only partly coherent; and it entails recognizing the same about the parties that claimed to embody these qualities. We may think of the latter, indeed, to function much like poles in the magnetic sense—“polarized” and thus mutually influencing each other—which possess a greater or lesser degree of attractive power. This attractive power has many sources; ideology is only one of them, and not always the most important. Others may be more prosaic—the desire for sociability and comradeship; the need (in a time of desperate unemployment and poverty like the late Weimar Republic) for help with food, clothing, and accommodation. Even more important—and lying, in some ways, at the intersection of strictly ideological and more practical concerns—is the desire to live out deeply held cultural values even more important than official ideology (comradeship, solidarity, manliness, etc.), a point to which we will return below.

The metaphor of the poles has one important practical consequence: it allows us to avoid the confusion inherent in referring to the space “between” the radical extremes where, under the “spectrum” metaphor, should lie the political middle. But there are other, more profound analytical consequences. One of these is that it allows us to conceptualize a space around and between the two poles in which radicals operating within organizational boundaries (party members, paramilitary fighters) communicated with those outside of organizational boundaries (individual militants, radical publicists, members of rival groups, and so on). Here, a German term—Spannungsfeld—is suggestive. Usually translated as “area of conflict” or “zone of tension,” but possessing electrical connotations as well (Spannung can mean “current” or “voltage”), the term is suggestive of the area of mutual attraction/repulsion in which militants and ideas moved in complex interplay; the area in which competing claims were weighed, assessed, and acted upon, inside or outside of the formal boundaries of discrete political parties.23 In this study, the area “between” the “radical extremes” is to be understood to mean precisely this zone of conflict, the second of our spatial metaphors.

The interaction between militants belonging to political movements and those in the zone of conflict is important for two reasons. First, as observed earlier, the discourse out of which the two movements constituted themselves was in part a creation of those outside the movements, and indeed, it was precisely these militants to whom the extremist movements often tr...