![]()

CHAPTER ONE

WORK, URBAN LIFE, AND THE EXPERIENCE OF EXPLOITATION

This chapter is dedicated to the study of the social and economic scenario in Rio de Janeiro in the period embracing the second half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. It is concerned with urban demography and the distribution of the working population between the categories of enslaved workers and free workers; with labor relationships and the profile of the labor force within industries and in the streets; and with living conditions in general. Discussing these themes in a specific chapter does not mean considering them to be part of a “structure” that precedes other levels of class manifestation and explains or determines them. We heed Thompson’s warning, based on Marx, whereby instead of attributing primacy to the “economic” and relegating norms and culture to the sphere of secondary reflections, the study of class formation should pay most attention to “the simultaneity of expression of characteristic productive relations in all systems and areas of social life.”1

The division of the present exposition however, obeys a logic that goes beyond the simple didactic organization of thought. Based on the concept of experience, I believe that it is possible to establish an idea of a process and of a relation in which material life and consciousness interact in this “simultaneity” to which Thompson refers. Starting from the discussion on the fundamental Marxian assertion that the social being determines social consciousness, Thompson puts it in precise terms by refuting the association between “social being” and “economic” or “base” and by reintegrating the strong sense of the concept of mode of production—“in which relations of production and attendant concepts, norms, and forms of power must be taken together as one set.”2 For that reason, the British historian affirms that “in any given society, in which social relations have become set in class ways, there is a cognitive organization of life which corresponds to the mode of production and the historically evolved class formations.”3 Seen that way, the conflictual dynamics of the social dimension take on a less simplistic meaning. The category of determination is not excluded from the interpretation, but acquires greater precision:

In order to explain this reevaluated—not only “economic”—material determination, Thompson makes use of a concept that plays the role of a “junction point,” i.e., experience: “What changes, as the mode of production and productive relations change, is the experience of living men and women. And that experience is sorted out in class ways, in social life and in consciousness, in the assent, the resistance, and the choices of men and women.”5

Hence for Thompson, in keeping with the best, or one of the best, Marxist traditions based on the concept of experience, high regard for the role of the subject in history is compatible with the refutation of the liberal perspective of the autonomy of a conscious subject who acts rationally and with a free will in the world (or in the market). In his polemic with Althusser’s structuralism, the English historian highlights the importance of experience, an “absent term” in the works of those he criticizes:

Therefore, although this work’s attention is directed toward organizations, actions, and the consciousness that outline a process of class formation, it would be incongruous to take the above considerations as references without clarifying which “determined situations” we are addressing, i.e., in what sphere of material transformations the experience of enslaved and free men and women who worked in Rio de Janeiro during that period was molded.

Which Labor Market?

In the course of the nineteenth century and in the first decades of the twentieth century, Rio de Janeiro kept its political-administrative importance as the seat of the government, first as the Neutral Municipality of the Court during the imperial period, and after 1889 as the Federal District in the Republic. Regarding the economy, the city’s commercial growth during the second half of the nineteenth century was driven by its distribution of imported products and its handling of the outflow of the coffee production of the Vale do Paraíba. What originally made such economic growth possible was the relative autonomy that Rio de Janeiro’s market had enjoyed in relation to Portugal since at least the preceding century, which had led to the emergence of great fortunes among the big traders established in the city (wholesalers, importers/exporters, and, especially, slave traders) and a consequent mercantile/urban accumulation.7 It was here too that the first industrial establishments of a relatively large size appeared. Furthermore, the country’s financial transactions largely depended on banking institutions based in Rio. The figures of the city population increase are significant.

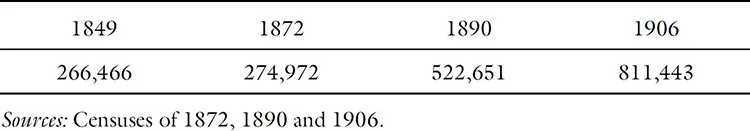

Table 1.1 Total Population of the City

The first findings of the researcher who combines such demographic data with the occupational statistics is the extreme diversity in the constitution of the labor force, which leads to difficulties in defining who the urban workers were, and the task becomes even more complex due to the relatively abrupt changes in its constitution over the course of the century.

Thus, according to the 1821 census, Rio de Janeiro (urban and rural parishes) had a total population of 112,695 inhabitants, of which 55,090 were slaves and 57,605 were free workers.8 In 1849, the census survey pointed to the existence of 266,466 inhabitants in the city, of which 110,602 were enslaved and 155,864 were free.9 In 1872, the number of slaves had fallen to 48,939, while the city’s population had grown to 274,972, of whom 226,033 were free inhabitants. Many reasons can explain these changes. First of all is the importance of the African slave trade’s contribution to the formation of the urban labor force.

Paul Lovejoy estimates that a total of around 3.5 million slaves were exported from Africa through the Atlantic routes during the nineteenth century.10 Manolo Florentino has calculated that 700,000 Africans landed in Rio de Janeiro in the period between 1790 and 1830 alone.11 Leslie Bethel estimated that during the last years of the 1840s, 60,000 Africans a year were being brought to Brazil by the slave trade.12

The prohibitions imposed on traffic during the first half of the nineteenth century, culminating with the end of tolerance for the slave trade in 1850, led to a rise in the price of slaves due to the demands of the coffee production zones, which ended up stimulating slave trade from the cities to the rural areas.13 One cannot ignore the fact that the level of social tension (the whites’ fear of slave rebellions, in particular) in the Americas’ largest black city was a further stimulus for diminishing the number of slaves in the court.14

The fact is that the spaces left by slaves were filled by free workers, many of whom were immigrants, in particular Portuguese. It would be a mistake, however, to consider that Portuguese immigrants arrived and took part in the urban labor force only after 1850. Gladys Ribeiro estimates that, in 1834, five thousand Portuguese plus two thousand foreigners of other nationalities corresponded to around 30 percent of the entire population of free workers in the city of Rio de Janeiro.15 In any event, the arrival of foreigners, particularly Portuguese, after 1850 gained new proportions when compared to the total amount of the urban population. According to Luiz Felipe de Alencastro’s estimate, the Portuguese represented about 10 percent of the court’s inhabitants in 1849 and reached 20 percent in 1872, although their arrival was already decreasing by that time.16

In that light, Alencastro concludes that Rio de Janeiro’s labor market passed through three phases during the nineteenth century: “a first phase, entirely African, extends until 1850; a Portuguese-African phase, that goes on until 1870 and, eventually, a Portuguese-Brazilian phase,”17 taking into due account the presence of the Brazilian free and freed, which increased notably during this last phase.

One must be careful, however, in using the expression “labor market” when referring to that period. It was definitely not an ordinary free-wage labor market; slavery left its mark, sometimes more and sometimes less significantly, on the entire period extending up to 1888.

Among the specificities of urban slave workforce employment, the best known was the existence of enslaved individuals, trained in specialized crafts or not, who were offered by their masters for hire, as well as others who rambled through the city looking for occasional services in exchange for money. Such slaves, called escravos de ganho or ganhadores (money-earning slaves), were supposed to give a stipulated amount of money to their masters on a daily or weekly basis. They often lived on their own, subsisting on the percentage of money they were allowed to keep, and they definitely took part in monetary relations, although they were still the property of other people. This explains the diversity of professional specialization in Rio de Janeiro shown by the data gathered by Luiz Carlos Soares from the 1872 census. There he found the following slave professional groups: “‘servants and journeymen,’ 5,785, out of which 4,997 were men and 788 were women; ‘mariners,’ 527 (all...