![]()

Chapter 1

Placing the Field Sites in Their Context

A Demographic History

This chapter discusses the demographic context of the field sites researched in this study. After a brief introduction to the four research locations, I will provide an overview of their demographic history. The material presented here has been gathered, to a large extent, from interview narratives and genealogies collected to represent demographically relevant census data. The ensuing discussion revolves around three key inquiries: When and why did fertility increase in these regions? What constitutes a youth bulge in this context? What are the mortality patterns in these regions?

During the Soviet period, fertility rates rose almost without interruption, while since the mid 1980s a steady decline in fertility has occurred. According to Dhillon and Yousef (2007), if, due to decreasing fertility, a youth cohort exceeds any other cohort, the society is considered to be experiencing a youth bulge. Thus, youth bulges are not (only) a high percentage of children and young people in the populace but also a specific phenomenon associated with the demographic transition from high fertility to low fertility. In order to approach the question of ‘size’ from a demographic anthropological point of view, I will make use of different methods such as genealogies, narratives and basic statistics.

The interview excerpts with Zikir reproduced below, which pertain to demographic changes and their relevance to youth, constitute a narrative upon which I place great importance. The interviewee, a teacher, not only gives voice to the core questions analysed in this book but also confirms that the main theme developed here reflects daily concerns and discussions among Tajiks. In other words, demographic issues have not only become political and scientific matters but also matters of concern to the local population.

The Field Sites

My original plan entailed conducting research only in the Jirgatol district, but I ended up spending time in other locations as well. For instance, I had not intended to stay in Dushanbe, but due to several incidents (among them, visa problems and my child’s serious illness), I had to remain in the capital for quite a while. During my stay, I realized that my urban experiences were of great relevance to understanding the role of students and, in particular, state concepts of youth (Chapter 7). The capital plays a central role in the lives of rural people. As the economic centre of the country, and the centre of education (universities are located here), Dushanbe is also considered the ultimate symbol of modernity. Since young people from rural areas come here to study or work, Dushanbe has a high concentration of them.

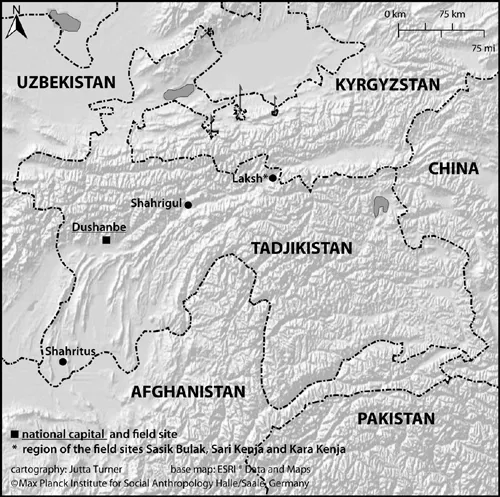

The main research locations that I selected are situated in rural areas, although Shahrituz could be classified as a small town. In each of the locations a large part of the population was sympathetic to the United Tajik Opposition (UTO) during the civil war.1 They include the area referred to as Lakhsh (two villages), Shahrituz (a neighbourhood within the small town) and Shahrigul (a village).2 Lakhsh, which lies in the Jirgatol district, is linked historically to Shahrituz. Several villages from this mountain district had been relocated to the cotton plantations in the Vakhsh Valley during the 1940s and 1950s.3 One of these villages constituted the neighbourhood where I conducted my research in Shahrituz. The neighbourhood had continued to maintain social relations, through intermarriage and economic exchanges, with those who had remained in the mountain regions. Moreover, during the civil war, many people from this neighbourhood in Shahrituz took refuge with relatives in Lakhsh.

Jirgatol is said to be Kyrgyz, and thus people from these areas are labelled with the ethnonym ‘Kyrgyz’ by outsiders, even if their native language is Tajik.4 The Kyrgyz constitute the majority of the population in Jirgatol, although their proportion has declined over the last decade due to a considerable increase in the number of Tajik people in many villages and to the extensive migration of Kyrgyz to Kyrgyzstan.

It is important to mention here that what constitutes an ‘ethnic’ identity is anything but clear in the context of Central Asia. Many of the ‘ethnic groups’ in this region evolved through census taking in the early twentieth century.5 Census categories and the politics of nationality transformed various fluid identifications into more fixed ethnic categories, officially declared in the passports of Soviet citizens. Ethnic cultures, within the realm of ethnographic research, came to be celebrated in folkloric representations, while at the same time they were marginalized as a remnant of the past, soon to give way to a single, common identity, Homo sovieticus (Mühlfried and Sokolovskiy 2011).

In Tajikistan national identifications have been described as weak because Bukhara and Samarkand were seen as the cultural centre of Central Asia’s Persian speakers, both these cities being were incorporated into the Uzbek socialist republic in the course of nation building in the 1920s (Rubin 1998; Roy 2000). Regional identification had historically served as an important marker of identification and, at least to a certain degree, laid down the dividing lines among militant groups in the civil war.

Administrative Divisions

Tajikistan is divided administratively into provinces. Khatlon province in the south includes the research site of Shahrituz. Sughd province is in the north, the main town of which is Khujand. The easternmost Pamir province enjoys a certain degree of independence as the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO). The central region – including the capital Dushanbe and the Rasht (or Qarotegin) Valley in the east, right up to the Kyrgyz border – is called the central province (Region of Republican Subordination).

The two research locations in the Rasht (Qarotegin) Valley are Shahrigul, situated in the district of Gharm in the Kamarob gorge, and Lakhsh in Jirgatol,6 which lies high up in the mountains, near the border with Kyrgyzstan. In geographical terms, this valley is usually referred to as the Qarotegin (Karategin in Russian). Politically, the name Qarotegin has been changed to Rasht. However, I will retain the geographical name of Qarotegin because it is more common and includes Jirgatol, which was my main area of research in 2006. The specific characteristics of the Jirgatol district will be dealt with in subsequent chapters. Every district is divided into jamoats* (municipalities) comprised of several villages, with one of these villages constituting the main jamoat or administrative centre.

A History of Qarotegin

The Qarotegin Valley, situated to the east of Dushanbe, has long been populated by the Kyrgyz. It is not clear when and why they arrived in the valley. According to one local version, the Kyrgyz were refugees who had come from territories further north and were allowed to stay in the mountainous regions by the emir in Bukhara. Another version states that they arrived seeking new pastures rather than refuge. The official version appeared in a book by Baltabaev in the Tajik and Kyrgyz languages in 2006, celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Jirgatol district. ‘The people of this viloyat [district] are of two kinds: first, the Özbak (qirgiz), and second, the Tojik’ (Baltabaev 2006: 26).7

In 1970, excavations were undertaken in Lakhsh, which apparently proved that phenotypical ‘Iranians’ had once lived there, before a landslide wiped out the entire village. This motivated the local Tajik to lay claim to the land, arguing that it belonged to their forefathers, thus systematically precluding any Kyrgyz claim.8 Bushkov and Mikul’skiy (1996: 3) identify two time periods during which the Kyrgyz are likely to have come from their place of origin in the south of the Ferghana Valley to Qarotegin, both dating back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – or more precisely, 1665 and 1758.

Figure 1.1: Map of Tajikistan.

Thus, the Kyrgyz version of history differs from the historical accounts in Baltabaev’s book on certain points. A local historian (who remembers local history in the classic Kyrgyz manner, through a recitative song called a dastan) mentions that several hundred years ago the Kyrgyz were authorized to live in the area by the central government in Bukhara. According to him, this is evident in the fact that all of the local places bear Kyrgyz names, even if the majority of the population today is Tajik.9

Earlier on, they had assured us that they would never lay hands on us – this was three to four hundred years ago, when Alim Khan [1798–1819] was the emir in Bukhara. At that time, the Tajik could not do anything, because we were in the majority here. Now the Tajik have come here, thinking they can tell us to ‘go back to your homeland (vatan*)’ . . . But they came after us, the Tajik. We have been here since 1406 – this year, that makes 600 years.10

The Tajik population of Lakhsh came to the region in several waves. According to family genealogies, sets of siblings arrived from the Bukhara and Samarkand regions (possibly as refugees). They first settled in the area of Tavildara; later, they migrated further to the upper valleys of Tavildara (Vakhyo) and Rasht, and the southern shores of the Muk-suu River.

In the 1920s, demographic pressure in the most remote mountain regions resulted in several significant population movements. Persian-speaking families – later to become Tajik citizens – split up, with some members moving to Kyrgyz settlements such as Lakhsh. These migrants came to Kyrgyz villages in search of opportunities. At that time, each village was headed by one or two (Kyrgyz) biys (local chiefs) who were in charge of land distribution (Martin 2001: 36). According to Kyrgyz elders, the first Tajik who had come were rather poor, looking for work (khizmatgor; n. khizmat*). They were given land by the landlords, on which they founded families (in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries). Other Tajik groups joined them from neighbouring valleys (such as from Khujaitov and Vakhyo) during the Stalin purges of the 1930s. Unlike the earlier migrants, those groups also included rich landowners who had fled the kulak persecutions.11

Lakhsh

The Lakhsh area is located approximately 300 kilometres from Dushanbe; however, due to poor road conditions, it takes an entire day’s journey to reach this remote area, which is only 50 kilometres from the Kyrgyz border. The jamoat (municipality) of Muk – named after the Muk-suu River – consists of ten villages, the largest of which is Sasik Bulak, which has a Tajik majority; Sari Kenja has a Kyrgyz majority, and Kara Kenja a mixed population. Muk is home to approximately 7,800 residents, about 2,900 of whom live in two villages (Sasik Bulak and Sari Kenja). The area of Sasik Bulak, Sari Kenja and Kara Kenja is also referred to as Lakhsh (I will make use of the term ‘Lakhsh’ to refer to the villages, especially Sasik Bulak and Sari Kenja, and their respective agricultural and pastoral land). Although the largest cultivated area is still state property, with its chief appointed by the district government (hukumat*), the present-day cooperative farm (khojagyi dehqonī) does not have to provide the state with agricultural produce on a regular basis; however, an informal transfer of products does occur in a slightly different manner (often on the basis of demand).

Bushkov (1993: 3–4) suggests the following population composition for Qarotegin: approximately 200,000 people lived in Qarotegin, Darvaz and Bald’juan at the beginning of the twentieth century. According to Bushkov, these residents were of mixed ethnicity, and at times, less than 5 per cent of the population was Tajik. It is not the percentage of ethnic groups that is interesting here but the fact that ethnic diversity was a common pattern of settlement and that recent figures show a rapid change in favour of the Tajik population. In the last decade, the Tajik have grown to outnumber the Kyrgyz in this region, also evidenced by more recent statistics of first-grade school pupils.12

The climate in Jirgatol is harsh, with a long winter (five months) and shorter spring, summer and autumn. Potatoes are called the ‘gold of Lakhsh’ because they are usually converted into cash and are valued as the area’s most important resource. Wheat, carrots and onions are produced solely for family consumption, and wheat production is usually not even enough to supply a household for the entire year.

Most people have cows (two to five) and goats and sheep (five to twenty) that spend the summer on the pastures (ailok*) and can be converted into cash at any time, usually when extra money is needed for a feast. Further, the milk is processed into butter and hard cheese. Some people also grow apples of high quality in plots near their houses, but due to the fruit’s recent appearance in the region, many people are not knowledgeable about how to store or market them, so the apples often rot in humid cellars and are among the most popular goods to be ‘stolen’ by children.13 Labour migration to Russia is relatively new and done on a smaller scale here compared to the other research locations, but the numbers of outbound migrants is rapidly increasing, bolstered by the success stories of those who return.

Shahrituz

Old Soviet maps situate Shahrituz in a forest. Presumably it was not until the 1940s that the forest was cleared to make room for cotton plantations. This does not mean that there were no settlements in this area before that time – villages such as Sayod and ...