![]()

Part I

Narratives

![]()

Chapter 3

Narrating the Self I

Moral Constructions of the Self as Paradigmatic Accounts

The previous chapter provided a conceptual framework for understanding human interactions as operations that construct the self and the other in a reciprocal activity through forcefully eliciting practices. The same operations simultaneously negotiate understandings of cultural practices and social knowledge. Subsequent chapters will show how much of this activity is telescoped in the accounts that people give about themselves, their lives and their achievements. The importance of narrative, then, is from the outset analytically bound up with the human interactions that are central to this study. The present chapter does something different: it uses older people's narratives to provide for these later accounts a backdrop of Kewa culture, a context of practices, events and expectations constructed in almost ‘doxic’ terms of taken-for-grantedness (Bourdieu 1977). Introducing the Kewa through life stories avoids the reification of culture usually encountered in first chapters of classical ethnographies, when we are given a ‘base’ on which the ethnographic edifice rests. Here, instead, old people simply talk about what they do or did. The chapter also begins the theoretical discussion of narrative which is at the heart of this study.1

The narratives I present throughout this book undergo two different kinds of divisions. First, they are divided into three generational sets that coincide with formal as well as substantive differences: in addition to having a different theoretical focus, each set will also be telling a different story, covering a different aspect of Kewa life and experience. Old people's stories (set 1) are presented in this chapter, the stories of those in their middle age (set 2) are the subject of chapter 4, and the stories of married adults in their thirties (set 3) follow in chapter 5. Second, the narratives are divided into two categories: maximal narratives and minimal narratives. ‘Maximal narratives’ are the life stories of people who were consciously and deliberately giving me accounts of their lives; ‘minimal narratives’ are accounts I have put together from a variety of sources and to which I have referred elsewhere as ‘portraits’ (Josephides 1998a). I borrow the term ‘minimal narratives’ from Carrithers (1995: 268), who defines them as ‘compact utterances’ which work through implicit inference. But while his work illustrates how such utterances evoke stories that ‘orient’ people in their understanding of events and actions, I have a different focus. My use of ‘portraits’ reveals my interest in how people's personhood is made up of a combination of the following elements: their own speech, actions and interactions; other people's perceptions of them; and their perception of other people and events. By sinking my concept of ‘portrait’ into the meaning of minimal narratives I include my own act of gathering such narratives together from a living mêlée of interactions. The concept of ‘portrait’ should also clarify why, despite the division I began with, ‘minimal narrative’ traces always cling to maximal narratives, linking personal stories with the actions and responses of others before the latter have been appropriated and assimilated. My minimal narratives are thus interactive, displaying the achievements of social action.

This chapter begins the debate on narrative with a consideration of the maximal narratives of the older generation of Kewa villagers. (Minimal narratives will be the subject of part II) As I string these together into an almost seamless account, a picture of precontact Kewa life emerges as a shared or interpersonal experience. In Carrithers’ (1992: 164) words, this is an example of the ‘consensibility’ of narratives. (Following Ziman 1978, Carrithers [1992: 155–56] investigates ‘reliable knowledge’ as resting on conceptual consensibility, that is, ‘the ability of people to perceive things in common, to agree upon and to share perceptions’). Thus one aim of this chapter is to depict, as far as possible, a shared culture as the baseline or background to the more contested picture of narratives in subsequent chapters. From another perspective, I link this consensibility to a crucial distinction in the theory of narrative – that between paradigmatic and narrative modes of thought (Bruner 1986). Though I do not argue that old people's maximal narratives contain paradigmatic knowledge (which is generic, impersonal and based on abstract reasoning), their stories undoubtedly claimed a certain generality for their personal experiences, thus serving as a cultural gloss. This generalization was made possible because of an implicit (or tacit) claim or assumption: that people's normal lives followed a general teleological path or had an ethical aim. I develop this argument only after a considerable adaptation of Ricoeur's (1992) contrast between ethics and morality.

In summary, this chapter will engage three questions in the following trajectory: beginning with a theoretical overview of the theory of narrative, it will contrast paradigmatic and narrative modes of thought, linking the older generation's narratives to a consideration of ethics and morality. At the same time it will show how the consensibility of narratives in this chapter paints a picture of a ‘shared culture’, even when accounts concern different aspects of that culture. This consensibility, finally, will be seen as deriving from the non-engagement with the future, and even the absence of the present, in the stories of those who spoke as if their lives were at an end.

Theories of Narrative

Jerome Bruner (1986: 14) writes that there are two modes of thought: the paradigmatic mode of philosophy, mathematics and the physical sciences, and the narrative mode of the human condition, concerned with the landscapes of action and consciousness. The powers of these modes are correspondingly different: ‘arguments convince one of their truth, stories of their lifelikeness’ (ibid.: 11). As a psychologist interested in the human condition, Bruner considers it more insightful to explore the ways we construct the world and create products of the mind, than to seek to establish the ‘ontological status of the products of these processes’ (ibid.: 45–46). Narrative, for him, ‘deals with the vicissitudes of intention’ (ibid.: 17), the intricate and tortuous steps by which we come to endow experience with meaning. An irreducible feature of the story is its joint placement in the space of action and in the subjectivity of the actors; thus the timeless underlying theme of a story – its fabula – is a unity that is achieved between plight, characters and consciousness (ibid.: 20–21). Three features make a narrative act powerful: the triggering of presupposition, subjectification (‘the depiction of reality not through an omniscient eye…but through the filter of the consciousness of protagonists in the story’ [ibid.: 25]), and multiple perspective (‘beholding the world not univocally but simultaneously through a set of prisms each of which catches some part of it’ [ibid.: 26]). These three features of narrative discourse make it possible for the reader to ‘write’ his own ‘virtual text’ – that is, read into the text a message other than the one the author intended. (For reader and author, substitute listener and speaker of oral narrative.)

These three features together succeed, in Bruner's words, in ‘subjunctivizing reality’. Bruner consults the Oxford English Dictionary on the use of the subjunctive, defined there as marking an action or state as expressing ‘a wish, command, exhortation, or a contingent, hypothetical or prospective event’ (ibid.: 26). This ‘as if’ trick of the narrative allows the narrator to mean more or less than she says – or, following my own theoretical discussion on elicitation, actively to modify that meaning – so narrative can only work with the active participation of the listener. Several narratives in this book will show how language is used to evoke subjective landscapes and multiple perspectives, by means of what Bruner (ibid.: 29) calls mode, intention, result, manner, aspect and status. These evocations successively transform the story, and permit its discourse ‘to acquire a meaning without this meaning becoming pure information’ (Todorov 1977: 233. For further discussion of ‘story’ versus ‘information’, see chapter 6 and Benjamin 1968). In this chapter, the ‘multiple perspective’ emerging from the differently positioned narrators results in a ‘cultural gloss’ which nevertheless portrays individual persons as originators of cultural life, rather than having that cultural life thrust upon them.

Narrative and Paradigmatic Thought

In his major study on culture, Michael Carrithers engages Bruner's formulations through his own ethnographic stories. I will let Carrithers lead us back to the distinction, crucial for the narratives discussed in this chapter, between paradigmatic thought and narrative thought. Narrative thought, as Carrithers expounds it, is the capacity to understand multi-faceted human interactions (‘deeds and attitudes’) and plots which show, as part of an unfolding story, the ‘consequences and evaluations of a multifarious flow of actions’ (Carrithers 1992: 82). The three requirements of a story is that it must show the flow of events, display the attitudes, beliefs and intentions of specific characters, and reveal the relationship between those events and attitudes or intentions (ibid.: 98. See p. 170 for a detailed account, especially with reference to the robustness of the story and its independence from its use by the anthropologist).

To demonstrate the difference between paradigmatic thought and narrative thought, Carrithers recounts, from his own fieldwork, two stories that purport to explain true religion or genuine Jainism (ibid.: 95–96). The first story, a cross between a sermon and a catechism and told by an educated man (‘Mr P’, glossed as ‘philosopher’), expounds in general terms on the spiritual quality of

aima as the essence of all religions. The second story, offered almost as a corrective to the first by the less educated ‘Mr S’ (‘storyteller’) after the overheard Mr P had left, begins instead with a specific character, whose single act of selflessness exemplifies the quality of

aima which then requires no further explanation. Mr S first negotiates a common understanding with Carrithers – did he speak Marathi? – and proceeds to establish a proper basis for the interpretation of his story by links to prior tellers (his grandfather) and geographic locations. Thus Mr S's account gains force, relevance and coherence by establishing a series of relationships which are laid out as tracks on which to roll the story. As Carrithers puts it, he was ‘[negotiating] relationships in order to negotiate meanings’ (ibid.: 106). From Carrithers’ mutualist perspective, ‘it is people in relationships who make things happen’ (ibid.: 111). Moreover, ‘things’ are particular events, not general precepts: Jains, we are told, understand Jainism through stories, and stories ‘exalt the particular’ as gossip (ibid.: 109).

Where do Kewa stories fit in this distinction between Mr P's paradigmatic mode and Mr S's narrative mode? To recapitulate, the narrative mode is concerned with the landscape of action and consciousness, by means of which we construct the world and create products of the mind; it deals with the vicissitudes of intention and how experience comes to be endowed with meaning. The timelessness of the story, being placed at once in the space of action and the subjectivity of the actor, is a unity achieved between plight, character, and consciousness; and the narrative act is made powerful by the triggering of presupposition, subjectification, and multiple perspective. The combination of these traits allows the listener to read into the narrative a message beyond the one intended by the speaker. Storytelling thus subjunctivizes reality, by implicating the listener and making her complicit in the unfolding meaning, but also arousing her desire for the action in the story. Narrative thought, in short, is the capacity to understand multi-faceted human interactions and plots as part of an unfolding story, and works by establishing relations as the proper basis for interpretation of the story.

While the stories in chapters 4 and 5 fit these criteria, the stories of the older generation in this chapter are not narratives in this sense. The minimal narratives of this generation (in this and later chapters) are better fits for this category, as are all portraits of people's engagement in the vicissitudes of current social life. The stories in the present chapter scramble narrative and paradigmatic categories. Though they are told in the first person singular, they are given as authoritative accounts that tacitly and subtly generalize personal experience, yet without forfeiting personal integrity: in elevating the self to the generalized subject of experience, the stories at the same time construct the individual self as a moral person at the centre of life's conventionalized dramas.2

Ethics, Morality and the Self in Paradigmatic Accounts

My use of ‘moral person’ needs qualification, to clarify what meaning of ‘morality’ is at issue here. Particularly relevant to my approach is the philosophy of Paul Ricoeur, who locates narrative theory at the crossroads between a theory of action and moral theory. Reminding us that narrative was part of life before (in literate cultures) being exiled from life in writing, he asks: ‘in what ways does the narrative component of self-understanding call for, at its completion, ethical determinations characteristic of the moral imputation of action to its agent?’ (Ricoeur 1992: 163). Ricoeur's linking of ethics with narrative and morality with action gives a good indication of the meanings he attaches to these concepts. The ethical aim is the general teleological aim for the good; it is the narrative moment in which the good life is described or envisaged. Morality, on the other hand, concerns duty and obligation, the deontological moment of action, as Ricoeur describes it, which becomes actualized in a moral norm (Ricoeur 1992: 219). These understandings of ethics and morality are associated, respectively, with Aristotle and Kant. To some extent they represent (and enforce) the tyranny of etymology, to which I am not obliged to submit. (Aristotle, after all, had only the Greek word at his disposal.) When I refer to ‘the moral self’ or ‘the moral person’ in this book I shall always mean the Aristotelian understanding of the ethical, and will not normally engage in discussion of specific moral norms as obligations. I hope that this explanation will forestall any confusion over my choice of the word ‘moral’, despite Ricoeur's distinction. I may still use the word ‘ethical’ to refer to a kind of life. But in the argument of this book ‘moral norm as obligation’ is merely the language of rehearsed talk, while the ‘deontological moment of action’ is part of the negotiation carried out in rehearsing talk.

How do elderly Kewa people's narratives construct a moral self, understood as the person who lives the good life described in the narrative? The concept of the good as the end-aim of the ethical life incorporates not only notions of how to treat others, but also criteria for self-esteem. For my argument here it may suffice to define the good as an end in itself. But it will be more helpful if I substitute ‘the good life’ for ‘a particular way of life’ or ‘this way of life’. Though the old people's stories may not be what Keesing (1985) has referred to as ‘moral texts’, they do give accounts of ‘normal lives’, and normal lives were implicitly good lives. The old people tell their stories with the assurance that this was how lives were lived, and their self-esteem is rooted in their embodiment of such lives. As in Benjamin's (1968) expression, narrators ‘sink’ the thing (of their stories) in their lives. The ethical, then, is exemplified in the paradigmatic, and Bruner's paradigmatic mode meets Ricoeur's ethical aim. Old people's narratives rest on a shared perception of how life was lived (Carrithers’ ‘consensibility’), with ‘is’ replacing ‘ought’ as the latter has no place in their narrative conceptual categories. In that sense the moral construction of the narrators’ lives is a paradigmatic account. Taken together, the accounts simultaneously construct a shared background and reveal the commonalities of people's lives. They scramble Bruner's and Carrithers’ categories, being personal stories implicitly oriented to ethical aims embodied in the narrator's life.

The Storytellers

I begin with a short introduction to the storytellers before moving on to the stories themselves. Wapa, Pupula, Ragunanu, Yakiranu and Payanu belong to the oldest generation of Yala villagers. The Kewa suffix -nu, meaning net bag as well as womb, denotes a feminine name; thus the last three names belong to women while the first two belong to men.

Wapa

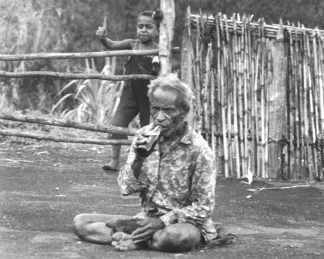

Wapa is my father. When Rimbu made me his sister, his father Wapa became my father too. Wapa seems entirely the product of those other, pre-contact days. Our worlds and experiences are widely different yet we are so cosy together, walking long stretches in companionable silence as he makes gruffly sociable noises. He always did his duty by me, bringing me pork and contributing to my feasts, now solicitously holding an umbrella over my head to protect me from the midday sun. Once, when my visit to the building site of my house dragged into the late afternoon, Wapa suddenly sprang up from among the sitting men, grasped my hand in a firm hold, and said: ‘It's getting dark, you will be going now.’ His gentleness and solicitousness revealed the charm he would have used on the women he wanted to procure as wives for his sons. As I write about him I catch my lips curling into a smile of affection. His laughter, deep and full, shook a fragile frame still taut and straight with muscle, and ended on a phlegmy, bronchial note. Only Coca-Cola was good for him when he was ill. A snapshot etched in my memory shows him sitting cross-legged, dishevelled, distant-looking and bleary-eyed, a half-drunk bottle of Coca-Cola in his hand. Yet how crusty he is as he struts up and down the settlement, threatening his daughter-in-law with his bow and arrow, flying off the handle when his nephew is passed over in food distributions, tackling Mapi the magistrate with a spear and summoning up warriors in defence of the peace. Wapa considers his irascibility an inalienable part of his personality as a warrior, quite beyond his control.

Plate 3.1. Wapa drinking Coca-Cola. (8 January 1980)

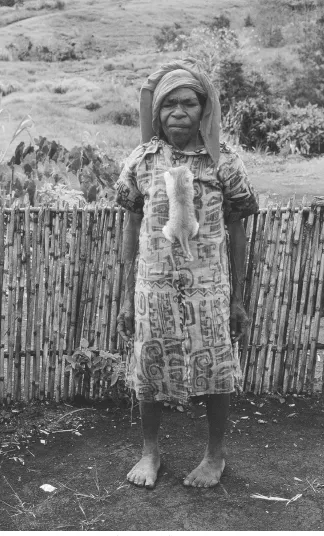

Plate 3.2. Payanu with granddaugher Wapanu. (April 1980)

Plate 3.3. Ragunanu with cat. (17 May 1980)

Plate 3.4. Pupula (right). (25 November 1982)

Plate 3.5. Yakiranu. (April 1980)

Lari, his daughter-in-law, thought she was too often at the receiving end of this warrior-temper. Once she summoned the magistrate on account of this. She was preparing to go to the ...