- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As tourism service standards become more homogeneous, travel destinations worldwide are conforming yet still trying to maintain, or even increase, their distinctiveness. Based on more than two years of fieldwork in Yogyakarta, Indonesia and Arusha, Tanzania, this book offers an in-depth investigation of the local-to-global dynamics of contemporary tourism. Each destination offers examples that illustrate how tour guide narratives and practices are informed by widely circulating imaginaries of the past as well as personal imaginings of the future.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

PREPARING A ROADMAP

The notion of globalization functions as an omnipotent metaphor, evoking images of a world in continuous motion, with people, cultures, goods, money, businesses, diseases, media, images and ideas flowing in every direction across the planet.1 The phenomena and processes that we think of as global refer implicitly or directly to border-crossing mobilities (cf. Urry 2007).2 The scholarly literature is replete with concepts and metaphors attempting to clarify altered or intensified spatial and temporal realities, including the experience of large-scale movements: deterritorialization and scapes; time–space compression; the network society and its space of flows; cosmopolitanism, and the possibility of leading bifocal and multifocal lives in several locations simultaneously through transnational migration. Some scholars have named this trend the ‘mobility turn’ in the social sciences, challenging their colleagues to change the objects of inquiry and the methodologies for research (Hannam, Sheller and Urry 2006). It is no coincidence that many of these academics developed their mobility framework while studying tourism, the business of travel for leisure, which is characterized by huge movements of people (tourists as well as tourism workers), capital (investments and tourist dollars), technologies of travel and the circulation of closely related tourism media and imaginaries (Sheller and Urry 2004). This book equally uses tourism as an analytical entry to examine issues of corporeal and imaginative human mobility with a global reach. However, before delving into the crux of the subject matter, it is essential to delineate the broader theoretical field within which this study engages and to refine the conceptual tools needed to approach and analyze the problems under investigation.

Travel Warnings

If you reject the food, ignore the customs, fear the religion and avoid the people, you might better stay at home.

–James Mitchener (writer; 1907–1997)

–James Mitchener (writer; 1907–1997)

While doing fieldwork at the Buddhist shrine of Borobudur, near Yogyakarta, I heard the story of Philip Beale. After having finished a study on Papua New Guinean traditional canoes in 1982, this young Englishman switched roles from researcher to tourist and explored neighbouring Indonesia. When he arrived on the island of Java, he visited Borobudur. There, he came across a 1,200-year-old carved stone relief of a vessel with outriggers like the wings of a bird. Beale was convinced this was the kind of boat daring Asian seafarers had used, even centuries before Borobudur was erected, to sail across the Indian Ocean to East Africa. This journey formed part of the ancient Cinnamon Route, which brought spices from the Indonesian archipelago to East Africa and then onto Egypt and Europe. Beale pulled together a team of experts to build a replica vessel and, in 2003, successfully made the crossing—aptly calling his project the Borobudur Ship Expedition.

Archaeological and historical research has shown that, after 600 BCE, an expansive Indian Ocean trading system developed (LaBianca and Scham 2004). This oceanic commercial enterprise was bounded on the east by the Indonesian archipelago and the lands surrounding the South China Sea, on the north by the coasts of southern India and Sri Lanka, on the northwest by the Persian Gulf and southern Arabia and on the west by the East African coasts, with Zanzibar as a stepping stone to sail further south and even around the Cape of Good Hope (Rofé 1980). Asian merchants brought to Africa many spices and the living shoots of banana and coconut trees, rice plants and various types of yams. They returned with ivory and rhinoceros horn, tortoise shells, animal skins and African slaves. Their perilous round-trip journeys took up to three years to complete. Although sailors from the Indonesian archipelago were among the earliest Asians to reach and settle on the East African coast, there is little material evidence left of this historical cultural exchange, apart from striking similarities between Indonesian and East African musical instruments (xylophones, musical bows and slit iron bells), board games and traditional canoes (Jones 1971).3 The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami served as a vivid reminder of the interconnectedness of the Indian Ocean region (and both Indonesia and Tanzania were hit).

The encounter I witnessed in Belgium between Indonesian and Tanzanian tour guides in 2002 (see Preface) is thus far from being a pioneering one, but inscribes itself in a long and rich history of human mobility and cultural contact. Clearly, globalization—‘the intensification of global interconnectedness, suggesting a world full of movement and mixture, contact and linkages and persistent cultural interaction and exchange’ (Inda and Rosaldo 2007: 4)—is not a wholly new phenomenon (cf. Featherstone 2006; Mintz 1998). Some might raise objections because the ancient Indian Ocean trading system or the Cinnamon Route never covered the entire globe, but very few present-day processes labelled as ‘global’ actually do (Cooper 2001). A major difference is that it does not take months and monsoons anymore to get from Indonesia to Tanzania (or anywhere else) and back. For many people, the ever-increasing speed, intensity and extent of globalizing processes is accelerating the experience of time and reducing the significance of distance, what Harvey calls ‘time-space compression’ (1989: 240). However, archaeological and historical records show not only that humankind has always been characterized by mobility but also that certain groups were actually more physically mobile in the past than they are now (e.g., nomadic pastoralist groups such as the Maasai).

A second caveat is that human mobility is spread very unevenly within societies and across the planet. The world may be full of mobilities and complex interconnections, but there are also huge numbers of people whose experience is marginal to or excluded from these movements and links. Processes of globalization are patently structured and regulated, such that while certain groups are permitted to travel and cross borders, others are not. For the very processes that produce movement and global linkages also promote immobility, exclusion and disconnection (Tsing 2005; Cunningham and Heyman 2004). Some people argue that ‘the West continues to travel to its peripheries for pleasure, whereas the reverse migration is still, by and large, rooted in the labour requirements dictated by the North’ (Gogia 2006: 373–74). However, this ethnography illustrates that the transnational movements of people are much more complex than a simple binary opposition between rich northern tourists and poor southern migrants.

Global mobility is clearly more than a mere metaphor; it is materially grounded. As any human mobility scholar knows, to assess the extent or nature of movement, or, indeed, even ‘observe’ it sometimes, you have to spend time studying things that stand still: the borders, institutions and territories of nation-states, and the (imagined) sedentary ‘home’ cultures of those that do not move. In other words, motion is always framed within a material and institutional infrastructure, and the circulation of people is constantly limited or promoted by economic coercions, political guarantees and sociocultural imaginaries. The incessant mobility that is often seen these days as characteristic of contemporary life is only one part of the story. Globalization processes have been overtheorized in terms of social openness while they remain undertheorized in terms of social closure. Human mobility has certainly increased worldwide, but attempts to control and restrict movement are just as characteristic of the era in which we live (Cresswell 2006). Moreover, the vast majority of people never moves to another place to settle—migrants, for instance, comprise a mere 3 per cent of the global population. This presents a serious criticism to the overgeneralized mobility discourse, which assumes ‘without any research to support it that the whole world is on the move, or at least that never have so many people, things and so on been moving across international borders’ (Friedman 2002: 33). In sum, border-crossing mobilities as a form of human experience are still the exception rather than the norm. Even migrants, who are depicted as icons of movement, ‘do not really spend that much time “moving” in the sense assumed by the notion of “mobility”’ (Hage 2005: 463).

Research on international travel shows that mobilities and borders are not antithetical. Modern passports, issued by the traveller's country of origin, and visas, issued by the destination country, did not come into widespread use until the First World War, and there would be no cosmopolitan travellers if there were no (national) boundaries to cross in the first place. An increasing concern with networks and movement, especially in the context of thinking about globalization and cosmopolitanism (largely theorized in terms of transborder travel), has stimulated theorizing on the changing nature of boundaries. State borders, for example, are not singular and unitary, but are designed to encourage various kinds of mobility (business travellers, tourists, migrant workers and students) and discourage others (illegal migrants and refugees). At transnational borders, one group's mobility seems to be facilitated at the expense of the other. The post-9/11 securitization era is full of examples showing how globalization dynamics produce significant forms of immobility for the political regulation of persons. This has led some scholars to conceive of globalization as consisting of systemic processes of closure and containment (Cunningham and Heyman 2004). Consideration of these themes breaks with theoretical tendencies that celebrate unbounded movement and instead focuses academic inquiry on the political-economic processes by which people are bounded, emplaced and allowed or forced to move. I follow this line of analysis by researching the mechanisms of tourism to developing countries that reinforce the imagined binary between mobile tourists and immobile locals.4

No Routes without Roots

Dwelling was understood to be the local ground of collective life, travel a supplement; roots always precede routes.

–James Clifford (1997: 3)

–James Clifford (1997: 3)

While studies of mobility can provide an innovative way to understand the multiple transformations that accompany globalization, they also seem to imply profound methodological and conceptual challenges for anthropology as a discipline (Gupta and Ferguson 1997; Tsing 2000). Clifford (1997) argued over a decade ago that ethnography needs to leave behind its preoccupation with discovering the ‘roots’ of sociocultural forms and instead trace the ‘routes’ that (re)produce them. This kind of thinking is further elaborated in Latour's (2005) actor-network theory, which transforms the social into a circulation. Some scholars, however, have conflated the excitement of so-called postlocal approaches in anthropology and that of new developments in the world ‘out there’, weakening the case for each. With the current hype over flux and change, anthropologists risk forgetting their own disciplinary origins. The idea and study of mobility has a deep genealogy in the discipline. It is already present in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century notions of (transcultural) diffusion, while French structuralists only developed it more fully in their thinking on exchange.

Anthropologists have known about cultural mobilities, movements infused with complex webs of meaning, long before the current vocabulary became fashionable, but most did not acknowledge this as it was not the focus of the discipline (Trouillot 2003). From Malinowski's pioneering fieldwork onward, the notion of ethnographers as itinerant and going somewhere, as practicing mobility, has been reinforced and reproduced, as has been the notion of ‘being there’ in a fixed place, even if only for a short period of time (hereby reasserting the implicit connection between culture and place). This continuing emphasis on place risks overlooking the constructed nature of all fieldwork and ethnographic fields, particularly in research projects where participants are highly mobile. Clearly, the interest in issues of mobility is not new to the discipline and ‘old’ anthropology can help us formulate answers to exciting contemporary questions (Salazar 2010a). I would argue that one of the great advantages of the researcher mobility of ethnographers is that we not only circulate geographically, moving between home and field, but also socially, moving up and down social hierarchies in our association with people often quite dissimilar from ourselves. It is in these encounters of difference that we are faced most palpably with boundaries—immobilities of others (often when ‘studying down’) and of ourselves (often when ‘studying up’). Such boundaries can be tangibly real or purely imagined. It is to the power of the human imagination that I turn next.

A World of Imaginaries

He that travels in theory has no inconveniences; he has shade and sunshine at his disposal, and wherever he alights finds tables of plenty and looks of gaiety. These ideas are indulged till the day of departure arrives, the chaise is called, and the progress of happiness begins. A few miles teach him the fallacies of imagination. The road is dusty, the air is sultry, the horses are sluggish, and the postilion brutal. He longs for the time of dinner that he may eat and rest. The inn is crowded, his orders are neglected, and nothing remains but that he devour in haste what the cook has spoiled, and drive on in quest of better entertainment. He finds at night a more commodious house, but the best is always worse than he expected.

–Dr. Samuel Johnson (writer; 1709–1784)

–Dr. Samuel Johnson (writer; 1709–1784)

We live in imagined (but not imaginary) worlds, using our personal imagination as well as collective imaginaries to represent our lifeworld and attribute meaning to it. Many of our daily activities—reading novels, playing games, watching movies, telling stories, daydreaming, planning a vacation, etc.—involve imagining or entering into the imaginings of others. The vernacular or unofficial imaginations people rely on, from the most spectacular fantasies to the most mundane reveries, are usually not expressed in theoretical terms but in images, stories and legends (long-standing objects of anthropological inquiry). They may take a variety of forms—oral, written, pictorial, symbolic or graphic—and include both linguistic and nonlinguistic ways of producing meaning.

Imaginaries, as representational assemblages that mediate the identifications with Self and Other, are ‘complex systems of presumption—patterns of forgetfulness and attentiveness—that enter subjective experience as the expectation that things will make sense generally (i.e., in terms not wholly idiosyncratic)’ (Vogler 2002: 625). Gaonkar defines them as ‘first-person subjectivities that build upon implicit understandings that underlie and make possible common practices’ (2002: 4). Although culturally shaped imaginaries influence collective behaviour, they are neither an acknowledged part of public discourse nor coterminous with implicit or covert culture (Thoden van Velzen 1995). They are imaginary in a double sense: ‘They exist by virtue of representation or implicit understandings, even when they acquire immense institutional force; and they are the means by which individuals understand their identities and their place in the world’ (Gaonkar 2002: 4). Paradoxically, human imagination helps produce our sense of reality. The imaginary can thus be conceived as a mental, individual and social process that produces the reality that simultaneously produces it (Figure 1).

Scholars from a wide array of disciplines have given attention to the imagination and the existing literature is vast.5 As I will show in the case of international tourism to developing countries, the analysis of imaginaries offers a powerful deconstruction device of ideological, political and sociocultural stereotypes and clichés. At the same time, I want to stress that imaginations are unspoken schemas of interpretation, rather than explicit ideologies. While they are alienating when they take on an institutional(ized) life of their own (e.g., in religion or politics), in the end the agents who imagine are individuals, not societies. A given group of tourists, for example, can participate in shared practices and can be exposed to discourses and symbols that evoke conflicting meanings, but tourists’ subjectivities are not completely expressed by collective imaginaries and have to be understood in their particularity.

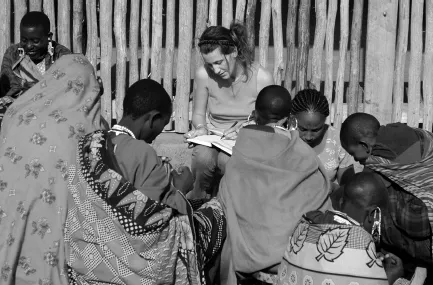

FIGURE 1 • Imagining Ethnographic Fieldwork…or Volunteering Abroad?

The notion of the imagination draws, among others, on Lacan's (1977) mirror phase in human development, when a child sees its own reflection as Other. This confused identification permits the appropriation of certain critical and valuable aspects of the Other as an essential part of the self. Not surprisingly, many imaginaries are structured by dichotomies—sometimes difficult to discern in practice—that construct the world in often paradigmatically linked binominals: nature–culture, here–there, male–female, inside–outside and local–global (cf. Durand 1999). An individual's propensity to produce imaginations is the primary fact; economy and politics provide triggering mechanisms, assisting in bringing idiosyncratic images together in socially acceptable formulas, but remaining secondary facts when studying the sociocultural production of fantasy (Thoden van Velzen 1985: 108).

Acknowledging the importance of learned cultural understandings but not conceiving culture as a fixed entity to be held in common by a geographically bounded or self-identified group, I distinguish between more widely shared imaginaries (both within and between cultures) and personal imaginations. International tourists, for example, may share some imaginaries with each other, but be fractured with respect to other cultural understandings, which can be shared among people who have had the same formative experiences despite living in different parts of the world and not having a common identity (e.g., tour guides). I will pay particular attention to how personal imaginations interact with and are influenced by institutionally grounded imaginaries implying power, hierarchy and hegemony. I will also discuss the multiple links between tourism and imaginaries of cosmopolitan mobility, focusing on the overlapping but conflicting ways in which cosmopolitan aspirations drive tourists, culture brokers and locals alike.

Going against the Flow

Is a railroad local or global? Neither. It is local at all points…Yet it is global…There are continuous paths that lead from the local to the global, from the circumstantial to the universal, from the contingent to the necessary, only so long as the branch lines have been paid for.

–Bruno Latour (1993: 117)

–Bruno Latour (1993: 117)

Critics have pointed out that much anthropological writing invokes vague notions of the global or globalization, rather than empirically analyzing them.6 The result are ethnographies situated within an imagined, if not imaginary, global context or studies of globalized processes that lack thick description, the texture of lives lived and identities constructed (Comaroff and Comaroff 2003). While calls for localization and attention to lived experience have become common in anthropologies of globalization, too often the act of imagining is detached from the specific forms, times and places through which people project their possible lives. Weiss warns us that ‘the analytical coupling of the imagination to processes of globalization has often obscured the wa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword: Circulating Culture

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1. Preparing a Roadmap

- Chapter 2. Two Destinations, One Destiny

- Chapter 3. ‘Seducation’

- Chapter 4. Imaging and Imagining Other Worlds

- Chapter 5. Guiding Roles and Rules

- Chapter 6. Fantasy Meets Reality

- Chapter 7. Coming Home

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Envisioning Eden by Noel B. Salazar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.