![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION: FRENCH STRIPPERS VIEWED FROM AFAR

Rappelons tout d'abord qu'il n'existe pas de discipline académique consacrée aux littératures dessinées. Un chercheur ne peut donc par définition se prévaloir de sa qualité d'universitaire pour asseoir sa compétence dans des matières qui ne correspondent à aucun champ disciplinaire ni à aucun programme de recherche.

Let us remember first of all that there is no such thing as an academic discipline dedicated to the literature of graphic art. By definition therefore it is impossible for researchers to take advantage of university status so as to assert their competence in a subject area that does not correspond to any field of study or programme of research.

Harry Morgan and Manuel Hirtz, Le Petit Critique illustré: Guide des ouvrages consacrés à la bande dessinée [The Illustrated Pocket Critic: A Guide to Secondary Studies on the Bande Dessinée] (Montrouge: PLG, 2005), p. 7.

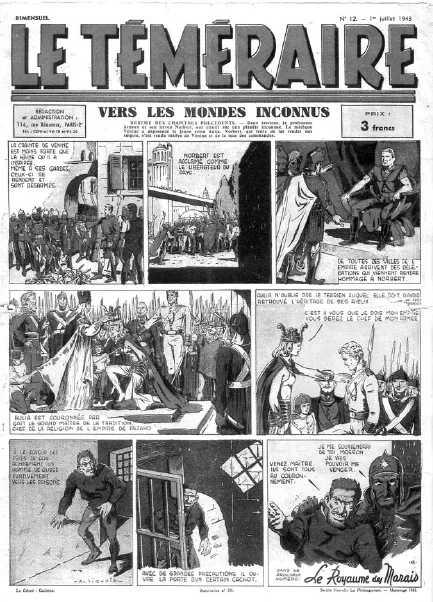

I recently opened my University of Glasgow Honours option on the bande dessinée (also known by its initials as ‘BD’) with the distribution of a single page taken from Le Téméraire [The Bold] (Fig. 1). The idea was that students would give an unprepared reaction, one which would then allow us to reflect on how to ‘read’ a bande dessinée, indeed how to define a bande dessinée, how to situate it historically, socially and in cultural terms, and what, if anything, a French or Belgian comic strip could teach us about life in general. The aims of that half-hour discussion are now the broader aims of this book.

Initial surprise turned to inquisitive deliberation as students soon realised that even without knowing the strip in question, Vers les mondes inconnus [Towards Unknown Worlds], the angles from which we viewed characters, the physiognomy and the layout of the space accorded to them allowed us to tell who were the ‘goodies’ and who were the ‘baddies’ (try it yourself, dear reader). Further information could be gleaned from the use of colours, or the way in which text – in narrative or speech format – imparted key information. The cinematographic qualities of the strip, and in particular its apparent mimicking of Fritz Lang's Metropolis of 1927, allowed us to reflect upon the nature of the BD as a mixed media text/image form, and on wider questions of the specificity of visual culture in general.

Figure 1. ‘Goul roi des Marais’. Le Téméraire, No. 12 (1 July 1943). Back cover.

Students had trouble putting a date to the strip (I had removed it from the handouts), with guesses pointing to the 1930s art deco style, or to the contemporary modernity of the science fiction intrigue. When the date was revealed students were able to spot the anti-Semitic and even anti-communist nature of the strip,1 although it was agreed that the propaganda was unquestionably subtle and for that reason effective. One student even pointed to the fact that Gaudron, the ‘Gérant’ or Managing Editor, was clearly a French rather than a German name, thereby raising the tricky question of wartime collaboration.2 The obvious influence of American strips such as Flash Gordon raised the pertinent question of France's cultural independence or, rather, its constant and ongoing transatlantic dialogue.

The fact that the discussion had to be cut short by time restraints underlined how heavily packed a bande dessinée can be, this despite initial reactions being hesitant, even along the lines of, ‘it's only a kids’ comic strip'. Because it was ‘only a kids’ comic’ it was felt that the possible findings were all the more interesting, as this represented an unlikely source of cultural richness, an everyday tap into France's history and society, into methods of expression and towards understanding the visual world that is increasingly our own. The overriding conclusion was that bandes dessinées were definitely worth a second look, a conclusion that hopefully will also be reached by the reader who finishes this book.

One further question raised was that of the extent to which the strip was primarily ‘foreign’. Would a group of French students have had the same reaction as a group consisting largely of Scottish students? To what extent did the students from other countries (Greece, Northern Ireland, England, USA) have a different take on the handout? On an immediate level we were aware that certain linguistic and, moreover, cultural references could be grasped less readily: the fact that Goul's despicable kingdom, the ‘Marais’, brings to mind the Jewish district of Paris was less than obvious to Scottish students.3 Perhaps more importantly, for students not having grown up with the bande dessinée as an everyday mass cultural phenomenon, the mechanics of the strip did not come as second nature, and the tradition of BD journals with leading ‘to be continued’-style features may have seemed less everyday.

On the other hand, English-language readers are perhaps more likely to grasp the debt to American culture and to seize upon the specificity of the adaptation to a French context. It seemed to me that Scottish students were more willing, in this instance at least, to engage with aspects in the strip relating to critical theory (the role of women, the colonialist implications) than their French counterparts might have been, and the element of cultural distancing meant that tricky issues such as that of wartime collaboration could be assessed with a different level of objectivity. For the same reasons that our discussion was far different from one that could conceivably have taken place at the École Européenne Supérieure de L'Image (L'EESI) at Angoulême,4 so this book, one of the first general studies in English on the French-language comic strip, does not do the same thing as the numerous works on the bande dessinée that are available in French.

There are several publications in English that will be relevant to the student of the bande dessinée. Randell W. Scott's European Comics in English Translation: A Descriptive Sourcebook (2002) gives bibliographic details and summarises the plot of bandes dessinées available in English, as well as giving notes on authors and translators and a brief but valuable list of secondary sources. The World Encyclopedia of Comics, edited by Maurice Horn,5 is one of a general number of works based upon alphabetical entries that include French-related information. As a specific monograph, Roger Sabin's Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art (2002 [first published 1996]) provides a colourful and thought-provoking overview of comics in their cultural context, and includes a clear précis of the French situation in the ninth chapter, ‘International Influences’ (pp. 217–35). Paul Gravett's Graphic Novels: Stories to Change Your Life (2005) gives a thematically linked descriptive selection of comic ‘greats’ that includes and contextualises works in the French language, and his website (www.paulgravett.com) continues to update such work. On the mechanics of the comic strip and related text/image theory, Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics and its subsequent volumes Reinventing Comics and Making Comics are essential reading.6 The success the translations have had in France bear witness to the works’ general import and relevance to the French tradition as well as to that of the USA.

Various early articles specifically on the bande dessinée have appeared in English-language press publications, such as a 1955 analysis of reactions in France to horror comics in the Guardian, a 1960 piece on Tintin in Newsweek, 1968 articles in Playboy and Penthouse on Barbarella, one in 1975 in the New York Times on Peanuts in France, and a 1978 overview of the work of Claire Bretécher that appeared in Ms.7 The Astérix phenomenon in particular has been the subject of much press ink, going as far as a front-cover feature in Time in July 1991. Inevitably such works have tended to be descriptive, presenting an unknown exotic commodity to a foreign audience and in general lacking the space (or sometimes desire) for original insight or analysis.

By contrast, Russel B. Nye's 1980 article on Astérix in the Journal of Popular Culture does provide an early description of a series now taken for granted,8 but it also contextualises the phenomenon in terms of the history of the comic strip, narrative strategies, the possible political content of Astérix, and its national specificity. Ten years later and on the other side of the Atlantic, a further landmark article in English was Hugh Starkey's ‘Is the BD “à bout de souffle”?’, a sixteen-page piece in the second issue of French Cultural Studies (number 1.2, 1990, pp. 95–110). Starkey was a pioneer in that, starting from the 1960s and moving forwards, he assessed the bande dessinée as a French cultural phenomenon in the way others had considered French literature or cinema, pointing to defining moments, analysing the specifics of the French form, and looking towards future trends. Often in a similar vein, the glossy Seattle-based Comics Journal has provided various snippets, starting in the late 1970s and still continuing, on the French and Belgian scene from Hergé to Enki Bilal and David B.9

Just as Paul Gravett's online musings (see above) and the Comics Journal are specific fora that have on occasion delved into the not-unrelated world of BD, so the International Journal of Comic Art (IJOCA), founded by John Lent from his base in Pennsylvania in 1999, has provided a number of articles on the French tradition, many of which I will draw upon in the pages of this current book. Early contributions included Pascal Lefèvre on the representation of the senses with specific reference to the francophone authors (issue 1.1, 1999), Elizabeth McQuillan on the development of the journal Pilote (2.1, 2000), Thierry Groensteen on Gustave Doré (2.2, 2000), Pierre Horn on the depiction of America in Les Pieds Nickelés [The Leadfoot Gang], Zig et Puce and Tintin (3.1, 2001) and Nhu-Hoa Nguyen on Claire Bretécher (3.2, 2001). As the IJOCA has become more established there has been an increase in the number of French-related articles, with subjects including Hergé and Franquin, Plantu, Jacques Lacan and superheroes, Chantal Montellier, Jacques Tardi, Lewis Trondheim, Edmond Baudoin and Le Téméraire's Vica.10 Nonetheless the IJOCA remains true to its roots with the vast majority of its pages dedicated to the tradition of the USA.

In North America 1999 saw the launch of the IJOCA; in Europe it was the year of the first International Bande Dessinée Conference in Glasgow, the event that would lead to the creation of the International Bande Dessinée Society or IBDS.11 Although a largely academic-based organisation of limited resources, the IBDS is important in that it represents the concretisation of the study of the BD as a discipline within English-language scholarship, a tangible sign of the will to place the bande dessinée on a par with French cinema or literature in general. The society's efforts led to the publication of The Francophone Bande Dessinée,12 the first work on the BD predominantly in English, whose various chapters explore the history of the form and its relationship with other disciplines such as architecture or sociology, whilst analysing the artistry of cutting-edge authors including Moebius, André Juillard, Baru and Enki Bilal.13

The early years of the IBDS also saw its members produce three doctoral dissertations in English on the bande dessinée. Elizabeth McQuillan's ‘The Reception and Creation of Post-1960 Franco-Belgian BD’ (University of Glasgow, 2001) outlines the key steps to the form's consecration in France and Belgium, whilst drawing upon case studies of Christian Binet, Claire Bretécher and Benoît Peeters and François Schuiten. Wendy Michallat's ‘Pilote Magazine and the Evolution of French Bande Dessinée between 1959 and 1974’ (University of Nottingham, 2002) places bande dessinée in its broader social context, looking at factors such as market pressures in a study that uses a BD publication, Pilote, as the key to an understanding of postwar French culture. Ann Miller's ‘Contemporary Bande Dessinée: Contexts, Critical Approaches and Case Studies’ (University of Newcastle, 2003) again introduces the reader to the defining moments and creations of BD history, but via the angle of applied critical theory, demonstrating the suitability of certain BDs to the most rigorous examination. Her key case study authors are Marc-Antoine Mathieu, André Juillard, Jean Teulé, Cosey and Chantal Montellier.

An updated and expanded version of Michallat's thesis is to be published by the New York-based Edwin Mellen Press, and in 2007 Intellect of Bristol released Ann Miller's Reading Bande Dessinée: Critical Approaches to French-Language Comic Strip, much of which is based on the work for her doctoral dissertation. In addition, Matthew Screech's Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity (Liverpool University Press, 2005) has provided a bio-bibliographic analysis of the form's development through seven main chapters, each based on one or more key creators: Hergé, André Franquin, René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, Moebius, Jacques Tardi, Marcel Gotlib, Claire Bretécher, Régis Franc, Alejandro Jodorowsky and François Bourgeon. In contrast to Miller's application of critical theory, Screech comes closer to the traditional l'homme et l'oeuvre approach, and as such provides an accessible introduction to readers with virtually no knowledge of the French and Belgian traditions of comics. So as not to reinvent the wheel, this current book has tended not to concentrate on authors already covered by Screech's and Miller's case studies.14

The twenty-first century has also seen a growth in English-language bande dessinée scholarship outwith Europe. The International Comics Arts Forum has held annual conferences in Washington since 1997, often with panels delving into aspects of the French tradition.15 More specifically, Mark McKinney, the main instigator behind the founding of the American Bande Dessinée Society in 2004, continues to work extensively on imperialism, colonialism and immigrant ethnicities in bande dessinée and has a corresponding monograph forthcoming. Bart Beaty, working from Calgary, examines in Unpopular Culture the rise of experimental comic artwork in Europe in the last fifteen years, paying particular attention to the work of L'Association, the French alternative publishing venture.16 Working from Australia, Murray Pratt explored the expression of gay identity and related issues through the BD, and has provided a chapter in The Francophone Bande Dessinée,17 as well as an article on Fabrice Neaud for Belphégor.18 Belphégor is a Canadian-ba...