- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Insightful commentary on the tangible relics of the Third Reich . . . Tells the history of the Nazi regime from a fascinating new perspective" (

Military History Monthly).

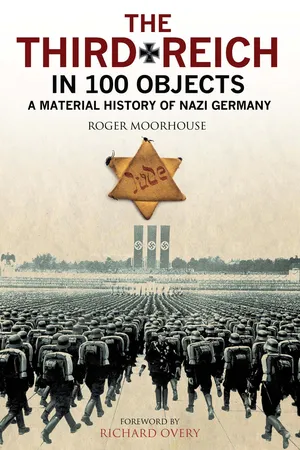

Hitler's Third Reich is covered in countless books and films: no conflict of the twentieth century has prompted such interest or such a body of literature. Here, two leading World War II historians offer a new way to look at the subject—through objects that come from this time and place, much like a museum exhibit.

The photographs gathered by the authors represent subjects including the methamphetamine known as Pervitin, Hitler's Mercedes, jackboots, concentration camp badges, a 1932 election poster, Wehrmacht mittens, Hitler's grooming kit, the Tiger Tank, fragments of flak, and, of course, the swastika and Mein Kampf, among dozens more—along with informative text that sheds new light on both the objects themselves and the history they represent.

Hitler's Third Reich is covered in countless books and films: no conflict of the twentieth century has prompted such interest or such a body of literature. Here, two leading World War II historians offer a new way to look at the subject—through objects that come from this time and place, much like a museum exhibit.

The photographs gathered by the authors represent subjects including the methamphetamine known as Pervitin, Hitler's Mercedes, jackboots, concentration camp badges, a 1932 election poster, Wehrmacht mittens, Hitler's grooming kit, the Tiger Tank, fragments of flak, and, of course, the swastika and Mein Kampf, among dozens more—along with informative text that sheds new light on both the objects themselves and the history they represent.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE OBJECTS

1 Hitler’s Paint Box

This battered, enamelled box of well-used watercolour paints – made in 1910 by the Nuremberg firm of Redeker & Hennis – once belonged to Adolf Hitler. Looted by Belgian war correspondent Robert Francotte from Hitler’s office desk in his Munich apartment, on Prinzregentenstrasse, in May 1945, it is evidence of an aspect of Hitler’s life and career that rarely receives scrutiny – his artistic pretensions.

If his account in Mein Kampf is to be believed, Hitler decided to become an artist at the age of twelve. Indulged by his adoring, widowed mother, he insisted that he would one day be a famous painter and dropped out of school in 1905 to pursue his dream. Two years later, he travelled to Vienna to enrol in the Academy of Fine Arts. Armed with a portfolio of his sketches, he was convinced, he later wrote, that he would ‘pass the examination quite easily’.1

Though his paintings are often derided, Hitler was certainly a competent artist. Even before he arrived in Vienna, he was scarcely without his sketchbook, and was constantly scribbling aspects of buildings that pleased him or designs for the stage sets of operas he wanted to write. As his youthful friend, August Kubizek, remembered:

A watercolour paint set that once belonged to Adolf Hitler.

On fine days, he used to frequent a bench on the Turmleitenweg [in Linz] where he established a kind of open-air study. There he would read his books, sketch and paint in watercolours.2

By the time he left Linz to live in Vienna, therefore, Hitler was confident of success in applying to the Academy, recalling that he had been ‘by far the best student’ in his school drawing class and that, since that time, he had made ‘more than ordinary progress’.3 He was to be frustrated, however. Though he qualified to sit the examination for the Vienna Academy, his drawings were deemed ‘unsatisfactory’ by the examiners, who gave the lapidary explanation that he had included ‘too few heads’.4 Crestfallen, Hitler doggedly pursued his dream, and the following year applied again, though this time without even qualifying to sit the examination. It was a rejection that would torment him until the end of his life.

‘Hitler decided to become an artist at the age of twelve.’

In the years that followed, Hitler would scrape a meagre living as an artist, selling his paintings and postcards, first in Vienna and later in Munich. During this period, he claimed to have painted as many as 700 or 800 pictures, asking around five marks for each. His style was straightforward, simple and naturalistic, using as his subjects mainly buildings, flowers and sweeping landscapes: ‘I paint what people want,’ he once said. He showed a fascination for detail, particularly architectural, but included very few human figures – an echo of his earlier failing.

With the outbreak of war in 1914, Hitler took his watercolours with him to the Western Front, where he painted and sketched his surroundings. The example opposite of his wartime work was painted in December 1914 and depicts a monastery ruined by shellfire at Messines, south of Ypres. It is unclear whether Hitler was still dreaming of a career as an artist by this point, or merely exercising his hobby, but it is notable that he spent his first period of leave in Berlin, visiting the city’s galleries.

Though he idly dreamed of once again applying for an art academy after the war, politics would soon take over his life. Thereafter, painting would be relegated to a few doodles and marginal sketches, not least among them some of the architectural sketches that would later resurface in the Germania plan to rebuild Berlin (see ‘Hitler’s Germania Sketch’, pages 101–2). In addition, Hitler’s tastes would dictate the artistic tone and cultural style of the Third Reich. He overruled Goebbels’s liking for modern art, and decreed that a dull classical style, presenting ideal Aryan families in mawkishly sentimental terms, should be the ‘official’ art of the Reich. He patronised such traditional artists as the neo-classical sculptor Arno Breker, while those more avantgarde artists who had flourished under the Weimar Republic, such as the Bauhaus designers, were forced into exile.

Hitler’s own paintings, meanwhile, were suppressed, with tame buyers dispatched to acquire those that could be located. Only a handful were ever published, and in 1937 exhibiting them was prohibited.5 By the later years of the twentieth century, they would become quite sought after by collectors, with some examples fetching over €100,000 at auction. Hitler’s watercolour set made a rather more modest €8,000, when it was sold in 2010.

Hitler claimed that his failure to be accepted into the Vienna Academy had made him ‘tough’, but it also rankled. More seriously, it marked a fork in his life; a point at which his dreams of becoming an artist receded, and his frustrations with the world grew. It is impossible to say for sure, of course, but perhaps that rejection contributed to Germany’s later catastrophe.

Aquarelle of a ruined monastery painted by Adolf Hitler in December 1914 while he was serving in the German Army.

1 A. Hitler, Mein Kampf (London, 1939), p. 30.

2 A. Kubizek, The Young Hitler I Knew (London, 2006), p. 40.

3 Hitler, Mein Kampf, p. 30.

4 F. Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics (London, 2003), p. 124.

5 Spotts, p. 140.

2 Hitler’s German Workers’ Party Card

On 12 September 1919, Adolf Hitler attended a meeting of a small nationalist political party in a Munich beer hall. The Deutsche Arbeiter-Partei (DAP or ‘German Workers’ Party’) had been founded earlier that year, during the chaos of the German revolution, by a Munich rail worker, Anton Drexler, in the hope of combining nationalism with a mass appeal. Hitler, who was still a serving soldier, was there to observe proceedings on behalf of the Army.

The precise process by which Hitler ended up joining the organisation he was supposed to observe is rather unclear, obscured by Hitler’s own self-aggrandising account and later Nazi mythology. Yet it appears that Drexler was sufficiently impressed when the shabby-looking Hitler stood up to interject that he later thrust a pamphlet into his hand. According to legend, he said of the newcomer: ‘That one’s got something. We could use him.’1

Hitler’s DAP membership card, number 555.

‘The card gives Hitler’s membership number as “555”, a blatant attempt to make the party seem larger than it was.’

In the days that followed, after Hitler perused the pamphlet, he was surprised to receive a postcard from Drexler informing him that he had been accepted as a member of the DAP and was duly invited to attend the next meeting. The party that Hitler joined was – according to his own account – a somewhat ramshackle outfit; with a tiny membership of barely fifty, it had no fixed political programme or basic organisation. At the meeting Hitler attended, the party’s total funds were reported to amount to 7 marks 50 pfennigs.2

It was only in January 1920 that the DAP issued formal membership cards. Hitler’s card, shown here, was dated 1 January. It gives his address at the army barracks, Lothstrasse 29, and was signed both by Drexler and the party’s record keeper, Rudolf Schüssler. It also shows Hitler’s name spelt with two ‘t’s, one of which has been crudely crossed out. Most curiously, the card gives Hitler’s membership number as ‘555’, a blatant attempt to make the party seem larger than it was. In truth, the membership list began at 501 and Hitler was the 55th member.3

By the time that Hitler received this membership card, he was already a rising star in the DAP. After making his speaking debut in October 1919, he began drawing sizeable audiences – larger than the party’s events had previously attracted – thereby swelling the party coffers and generating increased publicity. The DAP, it seemed, was on the move.

The breakthrough would come on 24 February 1920, when the party organised its biggest event yet – at the cavernous Hofbräuhaus in central Munich. There, before some 2,000 people, Hitler gave the DAP the direction that he believed it had lacked by promulgating a manifesto – the Twenty-Five-Point Programme – a curious mixture of anti-Semitic, anti-Marxist and anti-capitalist positions. That same evening, Hitler announced that the party had changed its name to express its political principles better; the German Workers’ Party was thereby transformed into the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazionalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – NSDAP). The Nazi Party was born and, barely six months after his first appearance, Hitler was already its primary motive force.

1 Various versions of the statement exist – see, for instance, Ian Kershaw, Hitler: Hubris 1889–1936 (London, 1998), p. 126, and Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939 (London, 2016), p. 87.

2 Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (London, 1962), p. 65.

3 Ullrich, Hitle...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Foreword by Richard Overy

- The Objects

- Acknowledgements

- Picture Credits

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Third Reich in 100 Objects by Roger Moorhouse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.