![]()

CHAPTER 1

WHY I LOVE RETAIL

You could smell the fresh popcorn as soon as you came through the front doors of McClellan’s five-and-dime on Hudson Street. The wooden floors creaked as you stepped toward the candy counter to the left or the toiletries department to the right, where a smiling young clerk would say, “Good morning!” as she waited to serve you.

If you passed by a little farther, you came to the second bank of counters. Sheets and towels were overseen by an older lady named Mrs. Duncan, while the toy department was enlivened by petite, energetic Ann, who was ready to kneel down and give any young boy or girl a squeeze. Nearby were the hosiery and lingerie sections, and on toward the back of the store came housewares, hardware, and pets. In charge of it all was a wiry, medium-height manager in his late fifties, Mr. T. Texas Tyler, who was always on the move.

McClellan’s sat on the east side of the courthouse square of Altus, Oklahoma, a county-seat town of some 20,000 in the middle of cotton fields and cattle ranches 220 miles northwest of Dallas. Not that our family came to shop very often at McClellan’s; we simply didn’t have the money. My father was the pastor of a church with no more than thirty-five attendees, which meant a tiny salary despite the need to put food on the table for six kids. We had no car; we just walked wherever we needed to go. Aunts and cousins from California would occasionally send us hand-me-down clothes, which helped a great deal. That way our parents only had to fill in the socks and underwear.

The church people were as gracious as they could be, supplementing the meager collection funds with weekly “poundings”—a time in the service when they would bring vegetables, fruit, or other foodstuffs (sometimes by the pound—hence, the name) to the altar to help the pastor’s family along. My mother accepted them all with warm appreciation. Still, we went weeks at a time without meat on our supper table. The idea of having an extra quarter or 50 cents we could spend at McClellan’s was far beyond our reality.

As a result, it’s little wonder that I didn’t feel comfortable at Altus High School, in the swirl of students my age who had new clothes and money for snacks. I was the kid off to the side, the kid washing dishes in the cafeteria in order to earn a lunch pass. It’s hard for me to remember any friends in high school. I’d already had to repeat seventh grade, and whenever I was required to stand up and give an oral report in front of the class, I froze in my seat. I simply couldn’t muster the courage.

“David,” the teacher would quietly say to me, “I’m sorry, but you must do this. If you refuse, I will have no choice but to give you an F.”

Under those conditions, I would definitely take the F. I still hadn’t recovered from the time a while back when I had mispronounced the word the, and everybody laughed. It was something about “the oven” or “the Industrial Revolution,” and I had said thuh instead of thee. My classmates thought that was hilarious.

So with a heavy sigh, my teacher would murmur, “Okay, you come back at the end of school today and give your report just to me, with no one else in the room.” That I was willing to do.

When I enrolled for my junior year in the fall of 1958, something absolutely wonderful happened. There on the class list was something called “D.E.”—Distributive Education (more commonly called Work-Study today). “What is that?” I wanted to know.

“Well, businesses in town call in to offer part-time jobs for students,” a young teacher named J. W. Weatherford explained, “and you get to leave during the school day to go work. You still get credit for the class, and you earn money along the way.”

I was thrilled with this combination. I quickly signed up for the D.E. class. And that’s how I entered the world of retail.

The first day that I left school at ten-thirty and walked the mile to McClellan’s, I was as excited as I’d ever been. “Welcome, son,” Mr. Tyler greeted me. “To get started, you go grab the yarn broom back there and sweep the floor.” This was dusty Oklahoma, after all, and the aisles needed attention several times a day. He taught me to sweep with a compound of sawdust with some light oil mixed in.

When that was finished, Mr. Tyler said, “All right, now let’s go upstairs to the stock room. I’ll show you how to check in the merchandise that just arrived.” We went up to a room on the second floor where there were bins for each department and a long worktable for unpacking the cartons that the trucks delivered to our little 5,000-square-foot store. I saw the conveyor belt that chugged upstairs to the stockroom from the freight dock in the back. I saw the hand-crank machine that turned out price stickers so we could mark the merchandise before the ladies took it downstairs to display. Yes, price stickers; this was long before the days of bar coding, and few items were prepriced by the suppliers.

That evening, after I walked the mile back to our house across the tracks, I excitedly told my mother about my day. “Now that I have a real job,” I announced, “I’m going to buy you something really nice!” I had worked alongside her and my brothers and sisters in the cotton fields for years to get money for our family. But this job at the five-and-dime was at a whole new level. I’d much rather be doing this than sports or clubs after school.

As a stock boy, I always carried two tools in my pocket: a case knife and a glass cutter. The second of these was because we were always making new bins on the countertops for individual items. Whereas today you might buy buttons or pencils in card packets that hang on wall pegs, back then items were offered in bulk, and customers picked out as many as they needed. Making the bins inevitably created lots and lots of leftover glass pieces. These congregated into a jumble in a space under the staircase, along with the various clips that held the panels together.

I took it upon myself to sort these glass remnants by size and bring order to the chaos. If I gathered all the three-inch pieces together, then the four-inch pieces, the five-inch pieces, and so on, they could be put to use again, instead of someone wastefully cutting into a large sheet of glass for just a small panel. It was a challenge that I somehow found to be fun.

I quickly fell into the rhythm of working forty hours a week, or even more. Three of my teachers eventually called me in to say that while my aptitude tests showed potential, my grades weren’t matching up. “Do you work or something?” one of them said.

With a smart-aleck attitude I responded, “Yeah, I probably work more hours than you do!” It’s a wonder I didn’t get suspended for that.

But retail was such a joyous contrast to the rest of my life. I had finally found something I was good at. Whenever I came to work, things were bustling. For instance, we cooked all of our own nuts for sale: Spanish peanuts, walnuts, cashews, hazelnuts. Spanish peanuts were 29 cents a pound. Also, there was bin after bin of orange slices and candy corn and coconut bonbons—it was a great atmosphere.

The Officers Club out at Altus Air Force Base would occasionally stop by with a huge order: two hundred pounds of mixed nuts. That meant I got to work at night cooking up large quantities of cashews, hazelnuts, and others, mixing them with oil in a big tub.

In the fall of the year, migrant workers would arrive to pick the area’s cotton, and on Saturdays they would inevitably gravitate toward our store. I was busier than ever filling the counters with merchandise, seeing it go out the front door, and refilling the counters. We loaded up on blankets—a dollar apiece—especially for the migrants, and sold a ton of them.

I studied what Mr. Tyler did. A lot of his work, I realized, was being a great organizer. He also knew the details of merchandise; he had an innate sense for what people would be willing to buy. The more I watched, the more I became convinced that I could be a store manager. I could be successful after all! This became my goal.

I didn’t wait on customers myself; they intimidated me. The men’s clothing store next door to McClellan’s tried to hire me one time, promising more money than I was presently making. But that would have meant dealing with customers, which scared me to death. So I stayed put, doing the physical labor at the five-and-dime so other people could make sales.

One time I was attempting to clean toilets, hardly touching the porcelain because I found the job distasteful, when Mr. Tyler came by. “Look, son—you have to do this job right!” he scolded as he plunged his bare hand into the toilet bowl and vigorously swished the cleanser around. I was amazed. He was a stickler for thoroughness, for organization, for detail.

More than once I saw him follow along after a customer who had put out a cigarette butt under his shoe. Mr. Tyler would reach down, pick up the butt with his hand, and put it into his pocket. Again, I could hardly believe my eyes. But he would not tolerate a sloppy store in any way.

He began training me in how to display merchandise attractively. In time I got to trim the display windows in the front. To me, a store window was like a painter’s canvas, with all the possibilities in the world. This work usually happened at night, because you had to get into awkward spaces, and you could spread out your items in the aisles as you worked.

One evening a few weeks before Easter, I made the mistake of building the display around chocolate bunnies. It looked very nice—until the hot sun hit the window the next afternoon. What a dumb idea. But in time, I got better at the job.

Mr. Tyler would take me down to the corner drugstore sometimes just to talk about the business. He’d drink coffee while I had a Coke, and he would pass along his wisdom. He’d update me on whether sales were growing or slipping. Sitting at that counter, I learned the fascinating concept of markup: that a store could buy something for 10 cents and sell it for 20, thus providing employment for the staff, and paying for the store’s lights and heat and rent and insurance—and maybe even having a penny left over in the end. Wow! Here was a way to make real money.

I began to see that in retail, the sky was the limit. You could always open more stores, or expand the stores you had; there was no end. I found this tremendously inspiring.

I never second-guessed my entrance into retail. I knew from day one that this was the way for me to go. I can become a manager . . . then a district supervisor . . . and maybe someday even start a business of my own.

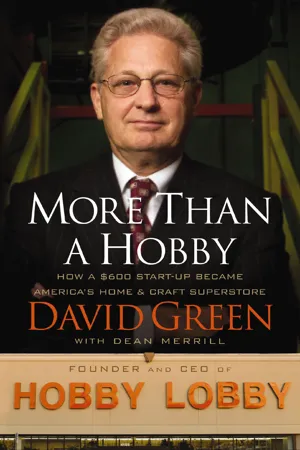

Obviously, I had not the slightest dream of what Hobby Lobby has become today: a chain of more than three hundred stores that gross a total $1.4 billion a year in sales. At that point, I was just excited to be making 60 cents an hour. I spent most of it on furniture for our home. I bought my mother a complete dining set, a sofa, and a refrigerator. There was nothing I would rather do with my earnings than give them away.

I did splurge a little, however, on a pretty, young part-timer in the stationery department, taking her across the street to the drugstore for a 5-cent Coke. If I was feeling really rich, we’d add a 5-cent ice-cream cone to the deal. Total outlay for the two of us: 20 cents. Today that young clerk is my wife, Barbara, who deserves as much credit for Hobby Lobby’s growth and success as anyone.

My first big purchase was a 1951 Ford, for which I paid about $200. Later, I noticed that Barbara’s current boyfriend drove a convertible, and I decided I needed to upgrade in order to compete for her attention. So I bought a yellow 1953 Ford convertible without even looking under the hood. It turned out to be the lemon that its color indicated.

From the very beginning, I loved the work—and that’s an important point: To succeed in retail, you have to love it. The process of bringing items in, displaying them attractively, and seeing them miraculously change into actual cash in the drawer has to get your blood racing.

FROM THE VERY BEGINNING,

I LOVED THEWORK—AND THAT’S AN

IMPORTANT POINT: TO SUCCEED IN

RETAIL, YOU HAVE TO LOVE IT.

You can triple the sale of an item just by how and where you display it. It’s some of the greatest fun in the world. There’s no way a corporate office should tell a local manager how to display every little thing. At Hobby Lobby we give some guidance, some photos of attractive merchandising, but the real magic happens at the store level. And when you see the results each month in your profit-and-loss statement, it can be very exciting.

I managed to squeak through high school and enlisted in the Air Force Reserve. After six weeks of basic training, I was assigned to Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, texas—not all that far from Altus. I hitchhiked home to see Barbara every weekend I could.

As soon as active duty was over, I returned to my job at McClellan’s. Barbara and I were married the following February; I was nineteen years old, and she was just seventeen. Her parents weren’t involved in retail; her dad was a heavy-equipment mechanic who worked for the coun...