![]()

CHAPTER 1

Psalms of Solomon and Romans 1:1 – 17: The “Son of God” and the Identity of Jesus

WESLEY HILL

The apostle Paul begins his letter to the Christians in Rome with a brief sketch of the key elements of his gospel. He describes this gospel as originating with God (1:1), foreshadowed in the prophetic writings of Israel’s Scriptures (1:2), and, finally, centered on the figure of God’s “Son” (1:3, 9). This Son, Paul says, was a Davidic descendant (1:3), raised in power through the action of the Spirit (1:4), and now dispenses grace and commissions certain people — notably Paul himself — to testify to his identity and saving power among all nations (1:5).

Although this summary is sequentially laid out and easy enough to follow, it nonetheless raises some thorny questions. What does it mean, for instance, for the God of Israel to have a “Son”? Does this mean that Paul lends some credence to pagan notions of fertility and procreation in the divine realm itself? And what does Paul mean when he says it was only at the resurrection that this “Son” of God was “declared,” or “appointed” (NIV), “Son of God in power”? Might this imply that Paul thought Jesus Christ was not the Son of God prior to being raised from the dead?

When asking questions like these, it is vital to keep in mind one of the basic canons, or rules, of biblical interpretation: we must focus not only on what is temporally “in front” of the text, but also on what is contextually “behind” it. In other words, when reading Paul, we must pay attention to the teaching about the “Son of God” that grew out of what Paul wrote — but in doing so, we must not overlook what Paul’s contemporary Jews were saying about the title and how that might have influenced the way Paul described Jesus’ role in God’s purposes.

Paul was not the first Jew of his day to use the term “Son of God.” Already in the OT the term had been used metaphorically to refer to God’s adopted “son,” the nation of Israel (Exod 4:22 – 23; Hos 11:1) and, by extension, the king of Israel (2 Sam 7:14; Ps 2:7). But in the Second Temple Period, Jewish writers had begun, like accomplished musicians, to play multiple variations on the theme of God’s Son. One example of this “traditioned improvisation,” as we might call it, is found in the Psalms of Solomon, a collection of eighteen poetic texts originally written in Hebrew in the first century BC and later translated into Greek and included in the Septuagint. This essay will explore Paul’s Christology in Rom 1 by way of Psalms of Solomon 17.

Psalms of Solomon

“RAISE UP FOR THEM THEIR KING, THE SON OF DAVID”

The Psalms of Solomon were probably composed at a time when faithful, law-upholding Jews felt besieged, both literally and figuratively. In Psalms of Solomon 17, the most prominent of the collection, reference is made to a warrior who arrives from the west, the land of the Gentiles (17:12 – 14). Probably this refers to the Roman general Pompey, who sacked Jerusalem in 63 BC only to die unburied, away from his homeland, in Egypt (cf. 2:26 – 27). Pompey’s action in the Jerusalem temple following his military conquest of the city was sacrilegious and elicited a renewed cry from observant Jews for divine judgment. But this was not the only obstacle faced by the writer(s) of these psalms.1 Unfaithful members of their own ranks, Hasmonean Sadducees who took control of political and religious functions in Jerusalem (17:6, 45; cf. 1:8), also led the psalmist to view himself and their law-observant way of life as under threat.

Consequently, the psalmist and his people turned to eschatology. Rather than make peace with Jerusalem’s current circumstances, they looked forward to the future arrival of the eschatological Messiah, who would right these wrongs and undo the present evil. In fact, according to R. B. Wright, “There is more substance to the ideas concerning the Messiah in the Psalms of Solomon than in any other extant Jewish writing.”2

The Messiah as Davidic Ruler. The psalmist begins the seventeenth psalm with an affirmation of God’s selection of David and David’s line for kingship in Israel: “You, Lord, chose David as king over Israel and you swore to him concerning his seed forever, that his kingdom might not fail before you” (17:4). Following this there appears a catalog of all that is wrong with Jerusalem’s present plight, focusing on the desecration of the conquering warrior himself (17:5 – 20). In response to this grim litany, the psalmist entreats God to intervene: “Behold, O Lord, and raise up for them their king, the son of David, at the time you know, O God, to rule over Israel your servant” (17:21).

The Messiah as Eschatological Agent. The kind of intervention the psalmist pleads for is decisive and violent. When the son of David appears, the psalmist hopes that he will both expel the marauding Gentiles from Jerusalem (17:22, 24) and deal with compromised Jews (the “sinners,” 17:23, 25). But in the wake of this destructive judgment, the psalmist also hopes that a new reign of righteousness and the cessation of violence will follow. The son of David will lead and judge a renewed Israel (17:26). He will subjugate the Gentiles (17:30), receiving their gifts as tribute (17:31), in much the same way Solomon himself welcomed the homage of the queen of Sheba (1 Kgs 10:1 – 13; cf. Isa 45:14; 60:10 – 14). This Davidic heir will be “a righteous king, taught by God, over them, and there will not be unrighteousness in his days among them, for all shall be holy and their king shall be the Lord Messiah [or Messiah of the Lord]” (17:32). This Davidic ruler, now identified as the “Christ,” the anointed one or “Messiah,” will have the “Lord,” the God of Israel, as his king (17:34). As he reigns, he will be sinless (17:36), empowered by the Holy Spirit (17:37), and the giver of eschatological prosperity and blessing to all who submit to his rulership (17:40 – 46).

In this way, the following picture emerges, according to the seventeenth psalm. There is a present order of things that is out of step with the psalmist’s hopes for the future. Externally, God’s people face political and military opposition from powerful pagan forces, and internally, they have to confront the compromised, unfaithful members within their own ranks. The solution to these problems is the appearance of the long-awaited descendant of David, the king of Israel’s golden age, who will bring the Gentiles into subservience and purge Israel of her own disobedient ones. This messianic figure will be the embodiment of what God himself had pledged in times past to accomplish, and so the psalmist can remain confident in the face of a bleak set of present circumstances.

Romans 1:1 – 17

“A DESCENDANT OF DAVID … APPOINTED THE SON OF GOD IN POWER”

The Messiah as Davidic Ruler and Eschatological Agent. Strikingly, Paul agrees with the author of the Psalms of Solomon that God’s Messiah is the son of David and is marked out for his role in God’s eschatological timetable by the action of the Holy Spirit, or “Spirit of holiness,” as Paul calls him.3 Romans 1:3 is the only place in Paul’s undisputed letters that he mentions Jesus’ Davidic descent.4 With this mention, Paul demonstrates that he has in mind traditions such as what we observed above in the Psalms of Solomon — that the Messiah would be David’s royal heir and the bearer of David’s mandate to shepherd and rule the people of Israel.5 Thus, when Paul calls Jesus the “Son of God in power,” he very likely means to say, “Jesus is the anointed eschatological agent of God’s final redemption of his people Israel.”

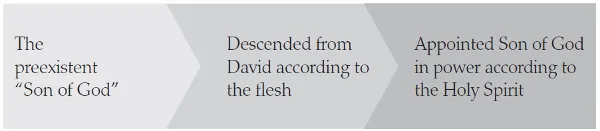

The Messiah’s Eternal Sonship. However, Paul makes at least two seismic modifications to the Jewish tradition and the messianic eschatological expectation he inherits. First, although he recognizes God’s raising of his Son through the Spirit to be the decisive public announcement of Jesus’ messianic identity, Paul makes it equally clear that this moment of messianic installment and acclamation happens to one who is already God’s Son, prior to his resurrection. Rom 1:3 – 4 says that Paul’s gospel concerns God’s “Son … a descendant of David … [who was] appointed the Son of God in power.” Hence, the one who is appointed “Son” was already, before that appointment, the “Son.” What Paul must have in mind, then, are multiple, succeeding chapters in the one Son’s biography. Paul’s line of thought seems to run something like this: God has a Son, known through the Hebrew prophets prior to the appearing of Jesus. The earthly life of the Son — his life “according to the flesh,” as Paul’s Greek literally reads — shows him to have descended from David. But there is another phase the Son embarks on after his death and resurrection — a new era, by virtue of God’s work through the Spirit in raising him, in which he enjoys power and can impart that power to specially commissioned spokespersons like Paul. Putting each of these biographical chapters together in sequence, we can see that it is the Son whom God already has in view when he imparts prophetic insight in Israel’s Scriptures; it is the same Son who stands in David’s royal line when he lives out his earthly existence in the shadow of weakness and frailty; and it is that same Son who is appointed to be not only “Son” but “Son-in-power” at his resurrection through the agency of the Spirit of holiness (see figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: The Son’s Biography in Romans 1:3 – 4

It was for this reason that Athanasius, the fourth-century church father, opposed the priest Arius for the latter’s teaching that the Son was less than fully equal with God the Father. Athanasius recognized that texts such as Rom 1:3 – 4 never envision a time when the Son is not “Son,” thus undermining any literal reading of this passage that might suggest how God became a parent at a certain point in time by fathering a Son. Rather, Athanasius taught, Jesus is indeed God’s Son, but this sonship is an eternal sonship — displayed in the time of Jesus’ fleshly life but not established or determined by that earthly existence.6 It is analogous but not identical to earthly, physical parentage and childbirth.

The Messiah’s Subjugation of Gentiles. Second, Paul also modifies the messianic tradition he inherits from texts like the Psalms of Solomon by redefining the nature of the Son of David’s victory. In Psalms of Solomon 17, the Messiah’s victory involves the exile of Gentile idolaters (17:22), their destruction and banishment (17:24), their separation from faithful Jews (17:28), their slavery and despoilment (17:30 – 31). True, the Messiah’s judgment will be tempered by compassion (17:34), but it will be no less discriminating for all that (17:45).

In Paul, we see an ironic reversal of many of these features of the psalm. Paul, the faithful Jew, is the one who is enslaved to the Messiah (Rom 1:1) on behalf of the Gentiles (1:5 – 6). The Mes...