![]()

Ezekiel

by Daniel Bodi

Introduction

The book of Ezekiel’s testimony unequivocally presents itself as having been delivered in exile during the Babylonian captivity. Based on the dating formulas in 1:2 and 40:1, Ezekiel’s prophecies extend for approximately twenty years, from 593 to 571 B.C. The prophet himself, however, was in Babylonia since 597, the date of the first deportation of the Jerusalem elite into exile. Ezekiel considers himself part of the community-in-exile. He views events in Judah from afar, described only by way of numerous visions and probably from personal memory of the last days of the Davidic dynasty. In 33:21, in the twelfth year of his exile, he receives news of the fall of Jerusalem from a fugitive.

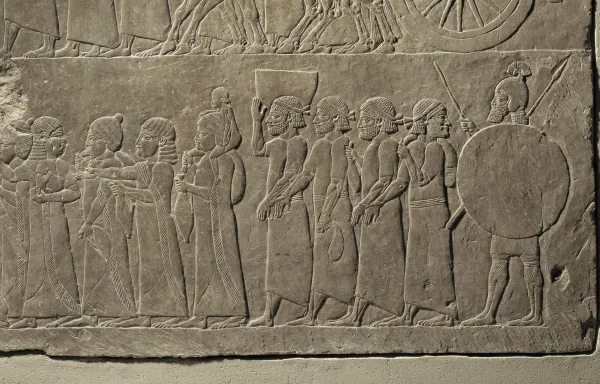

Ezekiel went into exile with the eight thousand nobility, craftspeople, priests, and religious personnel who were sent to Babylonia with the king Jehoiachin during the first deportation (2 Kings 24:14–16). He was a victim of a common policy of the Assyrians and the Babylonians: the practice of selective deportations. By removing political, spiritual, and economic leadership, the Babylonians aimed to break down national resistance, prevent any possibility of revolt, and bolster the economy and military machine of the conqueror’s homeland.1

The Aramaic language was increasingly becoming the lingua franca of the last days of the Babylonian empire in the sixth century B.C. Concerning the Late Babylonian language spoken at that time, the foremost Akkadian grammarian W. von Soden describes it as a Mischsprache or a mixture of Akkadian and Aramaic.2 Ezekiel’s extended stay in Babylonian exile accounts for the unusually high proportion of Aramaic and Akkadian words in his book and the numerous images and themes that have their background in his land of exile. Ezekiel is truly a product of his time and of his environment. As attested many times in the past, the literati and intellectual leadership of any age succeed in finding common meeting grounds despite political, social, or religious pressures intended to keep them separate. It is therefore conceivable that Ezekiel was able to converse with Babylonian scribes and religious leaders in Aramaic, acquiring knowledge of Akkadian literature, or at least its main themes, motifs, and metaphors.3

Ezekiel worked out his material carefully, sometimes laboriously writing like a scholar. Replete with obscure references, images, metaphors, and difficulties in text and meaning, both Judaism and Christianity have had problems in understanding this book. Judaism almost decided to exclude Ezekiel from its canon. By the end of the first century A.D. rabbi Hananiah ben Hezekiah, working numerous nights and having spent three hundred jars of oil for his lamp, was finally able to explain the passages in chapters 40–48 that seemed to be out of keeping with the teaching of the Torah or the Pentateuch and salvage the book from being excluded from the canon of the Hebrew Bible.

But even with the work of Hananiah, all the difficulties were not solved. Regarding passages such as Ezekiel 44:31; 45:18, the Talmudic tractate Menahot 45a states that the problems will be solved only by Elijah when he makes known all truth in preparation for the messianic age. In the fourth century A.D., Jerome, whom the pope sent to Bethlehem to study Hebrew with the rabbis and revise the Latin translation of the Vulgate, despaired of ever understanding this profound work. He likened the study of it to walking through the catacombs of Rome where light seldom breaks through (Epistola 53 ad Paulinum).4 Calvin never finished his commentary on Ezekiel and Luther put forth no major effort toward its interpretation.

The recovery of the Akkadian background of Ezekiel can increase our understanding of a number of expressions, themes, and motifs that have been misunderstood, gratuitously emended, completely overlooked, or termed “obscure.” For example, Ezekiel 16 and 23 represent the two most difficult chapters in the Bible on account of the graphic and detailed description of the lewd behavior of two sisters Oholah and Oholibah, symbols of Jerusalem and Samaria. In chapter 16, however, the description of the willful abuse of a female body as a metaphor of Jerusalem’s straying from God has caused its censorship by different religious communities and readerships. The famous psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers found in it ample material to show that Ezekiel was schizophrenic. According to him, the hallmark of Ezekiel’s pathology is his belaboring of sexual imagery in order to depict religious unfaithfulness and his lingering on scabrous details, even in an age less prejudiced than ours on such matters.5

To see pornography in Ezekiel 16, as modern readers suggest,6 is the exact opposite of what the prophet is attempting to accomplish. As his goal of Ezekiel 16 and 23, the prophet is trying to provoke revulsion and disgust. These chapters contain some extremely daring images, and bringing the comparative material to the forefront makes them even more poignant. The method of interpretation adopted in this commentary heightens the force of the intended outrage contained in the prophet’s message that aims at provoking utter disgust toward idolatry.

The above negative judgments are excessive and erroneous. It is almost impossible to understand the startling images contained in chapters 16 and 23 if we do not place them in the cultural and religious context of the prophet’s land of exile. More than any other chapters in this book, these two are time-, place-, and culture-bound, and unless this is recognized, misunderstandings are bound to occur. It appears that the biblical writer has woven into his creation images, terms, and idioms taken from the contemporary religious, legal, social, and political reality. As I will try to show, Ezekiel’s description contains a reminiscence of the Mesopotamian Ishtar festival. Exiled in Babylonia, Ezekiel cannot have failed to be confronted with the grandiose and in many respects obscene Ishtar festival. Shocked by the practices he discovers in Mesopotamia, he draws heavily on the Ishtar cult as the epitome of idolatrous and religious straying of the nation.

![]()

Ezekiel’s Initial Vision and Call (1:1–3:27)

Kebar River (1:1). Ezekiel and his compatriots in exile have settled in the vicinity of the Kebar Canal. Hebrew nehar kebār is the equivalent of Akkadian nār kabari (“Kabaru Canal”). The fifth-century B.C. archives of the Murashu family of bankers who lived in Nippur mention it several times. It corresponds to present-day Nuffer, a city sixty miles southeast of Babylon (the site of the latter is situated about two hundred miles south of present-day Baghdad).7