![]()

1 Peter

by Peter Davids

1 Peter

Important Facts:

■ AUTHOR: Silvanus (Silas) and Simon Peter.

■ DATE: A.D. 64–68 (shortly before or after Peter’s martyrdom).

■ OCCASION:

• To encourage believers in northwest Asia Minor experiencing persecution.

• To instruct believers on how to relate to societal structures.

■ KEY THEMES:

1. Believers have a secure home and inheritance with Christ.

2. Believers should live holy lives following the model of Christ.

The Church in Northwest Asia Minor

We do not know when the church started in northwest Asia Minor. Paul planted churches in the southern Galatian region in the late A.D. 40s (Acts 13–14), but when he later tried to extend this work westward into Asia or northwestward into Bithynia, the Spirit prohibited him (16:6–7), apparently because the Lord wanted to use Paul in Macedonia and Achaia (Greece; 16:10). Paul’s interest in those areas probably means that he did not know of churches there, for his general procedure was to go where the church did not yet exist (Rom. 15:20; 2 Cor. 10:14). Did the Lord know that some of the people cited in Acts 2:9 had already carried the gospel there, or was it his plan to leave the evangelization of that area to someone else at a later date? What we do know is that about fifteen years later 1 Peter witnesses to the existence of churches throughout this area. We should probably think of house churches scattered throughout the area, the larger ones consisting of thirty to forty members—sometimes several in one city (collectively forming the church in that city) and sometimes only one. They would be loosely connected as Christians traveled through the area for one reason or another, bringing news about other Christian groups as they went.

One thing that we do know about the churches of this area is that they were largely Gentile in makeup. First Peter frequently refers to these Christians in terms that would not be appropriate for Jews.1 There is also none of the Jew-Gentile or circumcision-uncircumcision tension in this letter that is so common in Paul’s writings. While Jews probably lived in these areas, as Acts 2:9 indicates, most of the church came from people native to the region. This made rejection by their neighbors as a result of their commitment to Christ so much more painful, since they had gone from being completely at home in the culture to being social outcasts.

Despite the problems mentioned in 1 Peter, these churches survived. When Trajan sent Pliny to Bithynia as Senatorial governor about A.D. 112, Pliny discovered, as he wrote to Trajan, “The contagion of that superstition [i.e., Christianity] has penetrated not the cities only, but the villages and the country.”2 Pliny himself thought he could still stamp Christianity out, but he would fail and the area would remain a strong Christian center for centuries.

A Portrait of the Situation

When missionaries arrived in these provinces, people listened to the gospel and believed. As a result their lifestyle changed. First and foremost, they stopped worshiping the various gods of their empire, city, trade guild, or family, and instead worshiped only “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1:3). This change in behavior meant that they were now viewed as unpatriotic (worship of the genius of the emperor was equivalent to flag worship in modern America), disloyal to their city (since they would not take part in civic ceremonies involving worship), unprofessional in their trade (since guild meetings usually took place in pagan temples), and haters of their families (family gatherings and ceremonies also took place in temples, and household worship was thought to hold the family together). After all, no one was asking these Christians to believe in the gods (many of their neighbors did not really believe in them), but only to offer token worship as a sign of their familial or civic allegiance. People who were so obstinate as to refuse this simple duty surely had to be “haters of humankind,” as many in the Roman Empire considered them.

Second, they now followed a morality different from that of their fellow citizens. Previously they had enjoyed drunken parties and loose sexual morals, but now they demonstrated self-control in their drinking, eating, and sexual habits. This different behavior cut them off from their former friends, who thought that they had become weird (4:4).

The result of these changes in their lives was social ostracism: insults, abuse, rejection, shame, and likely economic persecution with the resulting loss of property. There is no evidence in this letter of official persecution, such as imprisonment or execution, but rejection, abuse, punishment by family leaders (owners of slaves; husbands of women) and perhaps occasional mob violence had certainly taken their toll. (Official persecution would come in the time of Pliny.) Their fellow citizens thought that these believers in Jesus no longer belonged in their city or family and were communicating that message loud and clear.

This is the situation that has come to the attention of our writer. He apparently does not know these Christians personally (the letter lacks the personal greetings found in many of Paul’s letters), but he is concerned about their situation. He will write to them, citing the general Christian teachings he is sure they know. He follows a threefold strategy in his letter: (1) to exhort them to stand firm in the light of the return of Christ, (2) to advise them on how to minimize persecution through wise behavior, and (3) to encourage them to consider where they do belong and what property they do own because they belong to Christ. These strategies should be kept in mind as one reads the letter.

![]()

Letter Opening (1:1–2)

Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ (1:1). It was standard practice in the ancient world to begin a letter by identifying the sender. Normally the sender was viewed as the person who either dictated the letter or requested someone to write it for him, not the secretary who wrote down the dictated words or, if trusted, composed the letter on behalf of the sender. Our letter is from Peter (meaning “Rock”), and since that was a common name, he identifies which Peter is writing, namely, the one who was sent or commissioned (the meaning of “apostle”) by Jesus Christ.

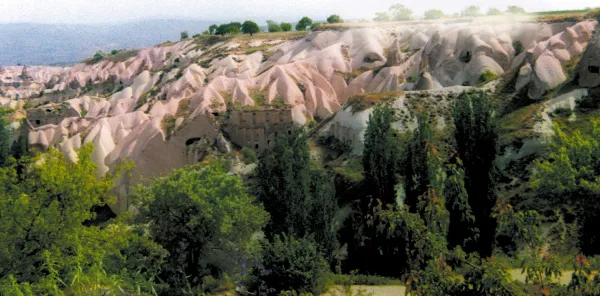

To God’s elect, strangers in the world, scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia and Bithynia (1:1). After identifying the sender, ancient letters identified the recipients. Peter is sensitive to the situation of his readers. Their society may reject them, but they are chosen (elect) by God (which idea is underlined in the next verse). They may be technically citizens of their various cities, but the way their fellow citizens treat them and the reality of their new life in Christ make them feel like temporary residents, noncitizens (both better translations than “strangers”). We will later discover where they really belong. At present they are scattered, which term would remind any Jews among them of the scattering of the Jewish people among the nations (called the “Diaspora,” a word from the same root as the term “scattered”) at the time of the Exile (586 B.C.) and the hope of their eventual regathering in Palestine.

The sanctifying work of the Spirit, for obedience to Jesus Christ and sprinkling by his blood (1:2). The idea that the Spirit sanctifies indicates not simply a positional change when God reached out to them, but a practical change in lifestyle for the better, from a less holy lifestyle to one that is set apart for God. This change appeared in their obedience to Jesus Christ. The basic Christian confession was “Jesus is Lord,” which contrasted with the assertion of the Roman Empire that “Caesar is Lord.” In both cases “Lord” implied that the person was someone whom you obeyed. It had practical consequences. This clash in allegiance was one cause of the persecution of the church. In chapter 2, Peter will set this clash of allegiance in perspective.

The image of sprinkling is taken from Old Testament and pagan sacrificial rites, with which the readers were surely familiar. They had all seen animals sacrificed and the blood sprinkled on people or objects for various religious purposes. Peter is probably thinking primarily of the Old Testament. For example, in Exodus 24:7–8 we read that the people respond to the law (which began with announcing God’s choice of them to be his people) with obedience, “We will do everything the LORD has said; we will obey.” As a result, “Moses … took the blood, sprinkled it on the people and said, ‘This is the blood of the covenant that the LORD has made with you in accordance with all these words.’ ” The sprinkled blood sealed the covenant and set the people apart for God.

Grace and peace be yours in abundance (1:2). A Greek letter normally had a greeting. In Christian letters this normal greeting (chairein, which in Greek sounds like the word for “grace,” charin, and so was changed to “grace”) was expanded with the Hebrew greeting (shalom = peace). However, it still retained its character as a formal greeting and thus functions like the “dear” that is often found at the beginning of English letters.

Thanksgiving (1:3–12)

Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! (1:3). A normal Greek letter followed the greeting with thanks to one or more of the gods for the benefits that had...