![]()

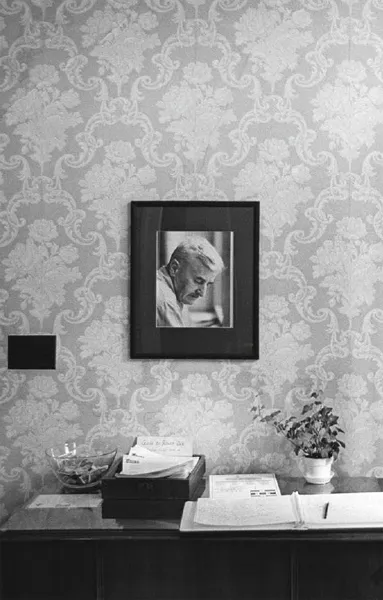

Rowan Oak, entrance foyer.

Courtesy of Robin McDonald.

Literary Pilgrimages

Over the years my wife Lynn and I have gone on a number of literary pilgrimages, usually by rental car for a few days. These trips produced some of my longest pieces, which were also great fun to write. Pulling into Oxford, Mississippi, after a violent thunderstorm; Greenville, Mississippi, just ahead of one; or Savannah, Georgia, as a history professor was murdered there were unforgettable experiences that served to get my creative juices flowing.

I have also included more unusual pieces about spending the night in a venerable Jesuit college library, as well as a powerful post-heart-surgery dream that went to the core of my most basic beliefs about art and the written word. Suffice it to say that the latter piece constitutes a literary pilgrimage of quite a different sort.

Stumbling on a Fossil of a Southern Dinosaur

We rolled into Athens, Ga., late in the evening. After pulling a few bags out of the car, my wife and I stumbled into our bed-and-breakfast, Magnolia Terrace, a 1912 Neoclassical mansion with a spacious front porch. Still jazzed from the road, I elected to wind down in front of the gas fire in the parlor before going to bed. As I stood warming my hands, a large, antique-looking book on a side table caught my eye. Old volumes are common in the restored furnishings of these kinds of establishments, and I’m always curious to see what the titles are.

It was a copy of the University of Georgia’s 1923 yearbook, Pandora. It was heavy for its size, and the cover featured a handsomely embossed motif of the school’s famous arch. I flipped the volume open and saw a small, neatly printed white label with the original owner’s name—“E. Merton Coulter.” I was astonished. My first thoughts were: “Why isn’t this in the university library with all his other books? How has it come to be here?” When I later asked the owner, she hadn’t a clue. “It came with the house,” she said. But Coulter had never lived at this address, which for years had served as a fraternity house.

E. Merton Coulter is hardly a household name unless you’re a connoisseur of Southern history, in which case he’s an infamous example of misguided scholarship in the service of bigotry. He was born in 1890 and came to the University of Georgia as a history professor in 1919. During his 40-year tenure there, he wrote 26 books and a hundred articles, edited the Georgia Historical Quarterly and served as the first president of the Southern Historical Association. Though primarily a state and local historian, he wrote two books in LSU Press’ History of the South series—The Confederate States of America, 1861–1865 (1947) and The South During Reconstruction, 1865–1877 (1952)—which were essentially apologias forcefully articulating his view that slavery was good for blacks and Reconstruction was an unmitigated evil for the South.

Coulter’s interpretation gained widespread traction, among Georgians in particular, through his popular middle-school history textbook, in which he reassured students that whites during Reconstruction “had a special plan” to keep the childish former slaves from doing themselves harm at the voting booth.

Coulter came by his opinions from his grandfathers, both of whom had been in the Confederate army. One was wounded at Gettysburg, and the other was accused of Klan violence after the war. Coulter absorbed their visceral hatred of Reconstruction from a young age. Late in life, as the civil rights movement unfolded around him, he remained unmoved and unreconstructed. “In my teachings I am still trying to re-establish the Southern Confederacy,” he declared.

Clarence Mohr, chairman of the University of South Alabama history department, was in graduate school at Georgia during the late 1960s and remembers Coulter as a retired dinosaur ensconced in a special office where he puttered amongst his books and papers. According to Mohr, most history students then, passionate about researching race and slavery topics, regarded Coulter as “an antediluvian figure.” None of these scholars bothered to submit papers to the Georgia Historical Quarterly because, Mohr said, they knew Coulter would reject them.

Mohr visited Coulter on several occasions, once to get advice on his thesis, and recalls, “My impression of him was of a very mentally alert and active old man.” That Coulter was a good storyteller and capable local historian, Mohr readily concedes but adds, “At his best he was never much of an analytical historian.”

Coulter had a large collection of books and manuscripts, mostly relating to Georgia history. Upon his death in 1981, the bulk of this material was turned over to the University of Georgia library. But some of the books were sold, according to Mohr, which could explain how Coulter’s 1923 Pandora came to rest in the parlor at Magnolia Terrace. Someone purchased it for a song, no doubt, thinking it a quaint bit of Georgiana that would make a nice conversation piece or an elegant base for a lamp or might provoke a few thoughts about the past. How right they were.

Mobile Press-Register, John Sledge, February 13, 2005.

© 2005 Mobile Press-Register. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

McMurtry’s Hometown a Paradise for Collectors

Neither the hotel clerk in Amarillo nor the attendant at the nearby Toot ’n’ Totum had ever heard of Archer City, Texas, much less how to get there. Yet this tiny, middle-of-nowhere place looms large on the American literary landscape as best-selling author Larry McMurtry’s hometown and the location of his bookstore, perhaps the biggest in the South. Therefore, during a recent cross-country jaunt, my wife and I decided to alter our route and experience Archer City’s rich and unusual associations for ourselves.

As it turns out, Archer City is located some two hours west and north of Dallas amid mesquite, bluebonnets, cattle and oil wells. The town presents anything but a prosperous appearance. A sandstone Romanesque Revival courthouse anchors a square lined with one-story businesses. Outlying houses are mostly one-story, too, and little traffic disturbs the somnolence induced by plentiful sun and sky.

Larry McMurtry (b. 1936) has both damned and honored Archer City with his works, some of which have been memorably filmed. He is the author of over 20 books, among them The Last Picture Show (its bleak indictment of small-town life stung many residents), Terms of Endearment and Lonesome Dove (winner of the 1986 Pulitzer Prize). McMurtry spent much of his career on the East Coast and ran a large used-books store in Washington, D.C., but after a 1991 heart attack he loaded up his inventory and came back home.

Nobody knows how many books McMurtry has, but most estimates start at 250,000 and go up from there. To accommodate them, he bought four nondescript masonry buildings on and near the square and opened for business under the name Booked Up. In a twinkling, the town that the author remembers as “bookless” during his youth became a mecca for bibliophiles. Out of the way as it is, Archer City, population 1,848, plays host to travelers from every corner of the globe, including literary celebrities like Susan Sontag.

On the day of our visit, McMurtry was out of town, so we contented ourselves with browsing the collection, neatly arrayed on floor-to-ceiling shelves. According to helpfully posted photocopied sheets, the stock is sorted “Erratically / Impressionistically, Whimsically / Open to Interpretation.” Building One houses the rare books, law and philosophy; Building Two, art, children’s literature, fiction and military history; Building Three, pamphlets, 18th- and 19th-century books; and Building Four, dance, drama, medicine, music, sports and travel. The books are in good condition and reasonably priced. There are few steals; after all, this is the domain of a deeply schooled collector.

There were only two clerks on duty during our visit, both pleasant, college-aged women. Customers are trusted to take their choices to the cashier in Building One for purchase. One of the clerks, Brandi Hilbers, was perched atop a stepladder in Building Four and took a short breather to answer a few questions. “You get to meet a lot of different kinds of people,” she responded when asked what she liked best about her job. Incredibly, she said that some locals were against the enterprise in the beginning, and that few patronize it now. Most customers are outsiders, many of them book dealers looking to build up their own inventory. Still, she averred, Booked Up is good for her community because “we bring in a lot of business.”

Before coming to work at Booked Up six years ago, Hilbers was an employee at the nearby Dairy Queen made famous by McMurtry’s elegiac memoir, Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen. Hilbers explained that the DQ celebrated by adorning the walls with McMurtry mementos. “My favorite part was when people came in about that,” she said.

So, in a steady trickle, from Tokyo, London, Chicago, Dallas, New York City and Fairhope, book lovers thread their way through the mesquite to revel in Archer City’s atmosphere and load up on books. My own purchase, a book I have long wanted but wasn’t consciously looking for (it was lying face up on an end table and caught my eye), was a massive paperbound copy of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project. As I plunked down the cash for this treasure, I wondered at the miracle of books—how a German philosopher like Benjamin who likely would be obscure to most Americans, has found renewed fame through the efforts of a north Texas wordsmith reared in the most isolated backwater imaginable. I’ll wager that most people who visit Archer City are equally well rewarded.

[Update: McMurtry considered closing the store in 2005, but happily it remains in business.]

Mobile Press-Register, John Sledge, May 30, 2004.

© 2004 Mobile Press-Register. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Drama of Story Comes Alive in Monroeville

None of us uttered a sound. We stood in the darkened, stuffy courthouse stairwell, deep in thought, eyes downcast, occasionally glancing at one another. This was in striking contrast to our behavior immediately before the trial. Then, cloistered in the same spot, we were laughing and cutting up while one of our number snapped Polaroids.

In the intervening half-hour we had learned the details of an ugly crime. A young white woman had been raped and beaten—by the black man in the dock, according to the prosecutor and public opinion, or by her own father, if the gentlemanly, eloquent defense attorney in the seersucker suit was right. Standing in that stairwell, we, the 12 white males on the jury, knew how we were going to vote, how we had to vote despite the spirited and heroic defense. There was no recourse.

Our reverie was interrupted when the sheriff appeared at the top of the stairs; “Y’all line up,” he said. We filed into the round courtroom with the pressed tin ceiling and took our seats. The muscular defendant sat behind a battered wooden table, subdued, his left arm in a red sling. He was a big man with a kindly face, now creased by care. The cowed plaintiff sat in the closest approximation of a fetal position possible in her hard chair. Her father, a coarse, unkempt man, glared at us as he leaned over his tarnished brass spittoon and sent a stream of black juice ringing into its bottom. The defense attorney studied us with a practiced eye, and I knew that he knew. The confident prosecutor wore a smirk on his face.

Ensconced in the creaky and perilously tipsy chairs of the jury box, we looked out over a sea of expectant faces. In the curved balcony, members of the black community, attired in their Sunday best, pressed against the rail. On the floor, the whites sat motionless, waiting.

The middle-aged judge leaned forward. He had done his best to be fair in this case and I reckoned he was anxious to get it over with. “Has the jury reached a verdict?” he asked.

The foreman extended the verdict to the sheriff who handed it to the judge. He opened the paper, paused, and then exclaimed “Guilty!” The courtroom erupted. Many of the whites were jubilant, clapping one another on the back and grinning. There was wailing in the balcony and one woman may have fainted. Other people simply sat dumbstruck. I slumped in my chair, drained and depressed by the trial. Here was a miscarriage of justice, and I was partly responsible for it.

Such was my experience last weekend in Monroeville at the annual drama based on Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird. During each performance, members of the audience are asked to play the jurors in the famous trial scene. Only white males may serve, as was the case in the small-town South of the 1930s. As a member of the jury (my profound thanks go to Spring Hill College English professor John Hafner for making it happen), I had an extraordinary opportunity to reflect on race and justice and how these issues are so deftly explored in Lee’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book. Also, I gained a valuable perspective on the power of literature to move hearts and minds. Standing in that stairwell waiting to render the preordained verdict, I felt the overwhelming weight of Lee’s lesson in a deeply personal way. To Kill a Mockingbird is easily the most important book ever to come out of Alabama. Read it, if you haven’t already. Then go see the marvelous play.

Mobile Press-Register, John Sledge, May 13, 2001.

© 2001 Mobile Press-Register. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

A Night in the Library

6:00 P.M. It is growing dark around me. I am standing in the reading room of the Thomas Byrne Memorial Library on the Spring Hill College campus. This is, beyond compare, the finest space devoted to reading in our city. As the day fades, I take the measure of this magnificent chamber: fully 100 feet in length, 50 wide and capped off by a soaring cathedral ceiling over 25 feet high, supported by heavy timber trusses. The wooden ceiling itself is constructed of alternating dark and blond boards, making it seem to rest lightly overhead. The walls are gray stucco, scored to resemble stone blocks. Gigantic wood-framed Palladian windows march around the room, affording splendid views of the surrounding campus. As it grows darker, the window...