![]()

PART ONE

The Education of a Sufi Shaykh

![]()

ONE

Initiation into the Sufi Path

By the time of his death in 784/1384, Makhdūm-i jahāniyān Sayyid Jalāl al-dīn Bukhārī1 was a widely respected Sufi shaykh and a recognized authority on Islamic religious practice and the Islamic intellectual traditions. Bukhārī’s later status was largely a product of his learning and Sufi affiliations. However, such acquired qualifications worked in concert with his inherited social status and group identity. Birth was insufficient to determine the ultimate place of an individual in society, but it was an important factor. As Roy Mottahedeh points out in his discussion of Iraqi society in the fourth/tenth and fifth/eleventh centuries, an individual’s pedigree included both “biological ancestry” and the noble deeds of his ancestors. “The great majority of men took a man’s genealogy, and the stockpile of honorable deeds that he inherited, into consideration both in estimating that man’s capacities, and in assigning him a station in society.”2 Besides such an inherited social status, however, this principle also influenced an individual’s choices in life, since he might feel compelled to live up to the nobility of his ancestors. Bukhārī’s life can be seen as an example of this process.

Family Background

Genealogy

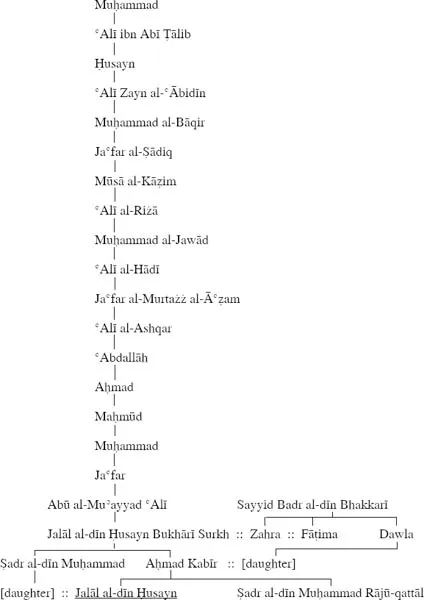

Jalāl ad-dīn Bukhārī was born in 707/1308 to a family with a definite social identity and status: sayyids (that is, descendants of the Prophet Muḥammad), originating in Bukhara, settled in the town of Uch, and affiliated with the Suhrawardī Sufi order. Bukhārī’s grandfather, also named Sayyid Jalāl al-dīn Ḥusayn and known as Shēr Shāh Jalāl Surkh (or Surkh-pōsh), had emigrated to India from Bukhara sometime in the early thirteenth century. Unfortunately we have little reliable information about Jalāl Surkh and must depend upon somewhat contradictory sources from several centuries after his death. Furthermore, the identical names of grandfather and grandson have understandably caused some confusion in popular legend, such that tales told of one figure have become attached to the other. To the best of our knowledge, Jalāl Surkh was born in 595/1198 in Bukhara to a family that traced its descent to ‘Alī al-Hādī, the tenth imam of the Twelver (Imāmī) Shi‘a.3 This family lineage also served as the chain of transmission for the khirqa (Sufi robe) with which Jalāl Surkh was initiated into the Sufi path by his own father, ‘Alī Abū al-Mu’ayyad.

The family’s descent from the Shi‘a imams and their use of the name Ḥusayn have lead to the suggestion that they were, in fact, Shi‘a.

4 Today, some branches of the Bukhārī family, including the one in control of the family tombs in Uch, identify as Imāmī (Twelver) Shi‘a, while others are Sunni. Support for the suggestion that Jalāl Surkh was Shi‘a can be found in

Maẓhar-i Jalālī, a putative collection of his teachings and one that refers to him by the very Shi‘a title of Ḥaydar-i

ānī (the second ‘Alī).

5 In contrast, his grandson Jalāl al-dīn Bukhārī Makhdūm-i jahāniyān presents himself as very definitely Sunni in his

malfūẓāt; while his teachings contain a great veneration for the family of the Prophet and especially for the twelve Imams, it was the Sunni Ḥanafī creed that he taught and practiced. When asked by members of the sayyid community in Medina about his

maẕhab, he answered, “the

maẕhab of Abū Ḥanīfa, along with all my forefathers in Bukhara,”

6 thus asserting not only his own identification with Ḥanafism but also that of his whole lineage. Bukhārī’s remarks on the Shi‘a identity of most of the sayyids that he met in Mecca and Medina, especially his use of the derogatory term

rawāfiż (turncoats), assume that Shi‘ism is foreign to himself and his audience.

7 Furthermore, Bukhārī was extravagantly praised by the historian Żiyā’ al-dīn Baranī, a strident anti-Shi‘a bigot, and patronized by Sultan Fīrōz Shāh Tughluq, who boasted of suppressing and humiliating his Shi‘a subjects.

8Could the Bukhārī sayyids have been secretly Shi‘a, practicing taqīya (dissimulation) to avoid persecution? Might Jalāl al-dīn Bukhārī’s statements be purposefully misleading? While this would be difficult to reconcile with Bukhārī’s career as a very public and erudite expert in the Sunni scholarly and religious traditions, it is not impossible. Devin Stewart has documented numerous cases of Shi‘a legal scholars participating in the “Sunni legal system,” mostly through public affiliation with the Shāfi‘ī maẕhab.9 During the 740s/1340s when Bukhārī was in Arabia, he studied with several leading Shāfi‘ī scholars. Furthermore, as exemplified by his statement quoted above, it seems that he was obliged to answer questions about his sectarian affiliation from various sides, suggesting that his contemporaries were not always certain of his Sunni identity. At any rate, whether it was a matter of conversion or of coming out of the Sunni closet, the family’s Shi‘a identity dates from after the eleventh/seventeenth century.10

Although the Bukhārī family’s illustrious genealogy did not necessarily indicate a sectarian Shi‘a affiliation, it did place the family into a specific social category, that of sayyids (descendants of the Prophet Muḥammad through his daughter Fāṭima). Being a sayyid was a significant aspect of Bukhārī’s public identity; in his malfūẓāt, he is often called sayyid al-sādāt (“sayyid of sayyids” or “master of sayyids”) and eulogized for the purity of his descent. Sayyids constituted and, in some parts of the world, continue to constitute a high-status group among Muslims, associated with religious learning, piety, and charisma.11 In eighth-/fourteenth-century India, the status of sayyids was formally recognized by the Delhi Sultanate. According to Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, sayyids and other religious dignitaries, such as judges, scholars, and Sufi shaykhs, took the “principal place” at Muḥammad bin Tughluq’s royal banquets, ahead of his own relatives and the nobility.12 One of the examples of Fīrōz-shāh Tughluq’s piety, listed by the historian Żiyā’ al-dīn Baranī, was his generosity to sayyids, as well as the ‘ulama, Sufis, and other religious figures.13

It is worth noting that in these examples sayyids are listed with religious professionals, even though, as a group, they had no defined social or religious function and might in fact, as individuals, have careers as scholars, judges, or Sufi shaykhs. That is, since a sayyid is categorized by his or her blood descent while the other categories are defined by professional qualification, there is obviously opportunity for overlap and, as mentioned above, the religious careers were considered particularly suitable for sayyids. Many of the great South Asian Sufi shaykhs were said to be of sayyid descent, including most of the early Chishtī masters: Mu‘īn al-dīn Chishtī, Quṭb al-dīn Bakhtiyār Kākī, Niẓām al-dīn Awliyā,’ and Naṣīr al-dīn Maḥmūd Chirāgh-i Dihlī.14 To this day, there is an assumption in South Asian Muslim communities that any saint or holy person is most likely a sayyid.

In the case of Jalāl al-dīn Bukhārī the status and label of sayyid tended to trump other acquired labels, a pattern found in other figures of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. One minor indicator of this is the seeming inalienability of the title sayyid from the name of any figure with the right to bear it, for example, Sayyid ‘Alī Hamadānī, Sayyid Ashraf Jahāngīr Simnānī, Sayyid Gīsūdarāz. In general, medieval South Asian Muslim culture was quite flexible as to which elements of a person’s name would be highlighted or forgotten, paying scant attention to the classical Arab distinctions of ism (personal name), laqab (honorific), patronymic, and so on. According to those distinctions, our subject would be more appropriately referred to as Ḥusayn or Abū ‘Abdallāh or Ibn Aḥmad rather than Jalāl al-dīn Bukhārī. Furthermore, Sufi shaykhs and saints were given a plethora of hyperbolic titles and nicknames by their disciples such as makhdūm-i jahāniyān (served by the inhabitants of the world), sulṭān al-mashā’ikh (king of shaykhs), shaykh al-akbar (greatest shaykh), quṭb-i ‘ālam (axis of the world). Yet, despite all this creativity and flexibility, we rarely find the name of a descendant of the Prophet without sayyid preceding it.

In order to preserve the purity of their lineage, sayyids frequently practiced endogamy—for a sayyida this was the only appropriate marriage since a Muslim, especially Ḥanafī, woman may only marry an equal or a better. Although the information on Jalāl Surkh’s life is sketchy and despite the general neglect of women in medieval Sufi texts, the sources are careful to mention that all of his wives were sayyidas. His first wife, whom he married in Bukhara and by whom he had two sons, Awḥād al-dīn ‘Alī and Ja‘far, is variously described as belonging to a family of Medinan sayyids and as the daughter of Sayyid Qāsim Bukhārī.15

Given the nature of the sayyids as an endogamous descent group, with a fixed status above others, and a religious justification for this status, it is unsurprising that attempts to identify caste or a caste-like system among South Asian Muslims have frequently listed sayyids as the highest caste.16 However, the question of whether caste exists among Muslims is a vexed one whose answer depends on how caste is defined. And though it might be analytically useful to view sayyids in the context of caste, it would be unwarranted to take this as an example of the influence of Indic traditions on Islam, since sayyids have been a high-status group in many different regions of the world. Furthermore, unlike Hindu caste systems, sayyids do not form part of an overarching hierarchical scheme theoretically incorporating all of society. In some ways, they stand out as a unique phenomenon in Islam: a pan-Islamic descent group maintaining its status in a range of Islamic societies, each of which is made up of various competing social classes, factions, and ethnicities.

Table 1: Genealogy of the Bukhārī Sayyids

Sacred Geography

Though we have no definite information on the dates or motivations for Jalāl Surkh’s emigration from Bukhara, it is probable that, like so many others, he fled the destruction and upheaval brought by the Mongol invasions of the 620s/1220s. He is said to have visited the holy cities of Mecca, Medina, and Mashhad before arriving in South Asia. His two eldest sons accompanied him to India but later returned to Bukhara.17 In India, Jalāl Surkh first lived in Bhakkar (near the modern towns of Sukkur and Rohri in Sind), where his relative Sayyid Badr al-dīn Ḥusaynī was settled. Badr al-dīn gave him his daughter in marriage. According to one account this was in obedience to the Prophet Muḥammad’s instructions given in a dream. The match lead to a rift with Badr al-dīn’s brothers and Jalāl Surkh’s departure from Bhakkar.18 Another account gives the bride’s name as Zahra and states that after her untimely death Jalāl Surkh married her sister Fāṭima.19 The couple had three sons: Ṣadr al-dīn Muḥammad, Aḥmad Kabīr, and Bahā’ al-dīn.20 From Bhakkar, Jalāl Surkh moved to Multan to attach himself to the Suhrawardī saint Bahā’ al-dīn Zakarīyā (577–661/1182–1262). Various dates are reported for his discipleship and his initiation into the Suhrawardī path; ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Lak’hnawī asserts that this took place in 635/1237, but according to Sawāl ō jawāb, Jalāl Surkh came to Multan when the Sultan of Delhi was trying to conquer Thatta and Bhakkar. That would suggest the 650s/1250s when Sultan Nāṣir al-dīn b. Iltutmish (r. 644–664/1246–1266) was attempting to quell the Sumra tribe in Sind.21 At any rate, Jalāl Surkh was eventually instructed by his spiritual mentor to move to the town of Uch, where he spent the rest of his life and where his tomb is still a site of devotional activity.

Today, Multan and Uch are part of the Pakistani province of Punjab, while Bhakkar is in Sind. At the time, however, the whole valley of the Indus and its tributaries, from Multan down to the sea, was referred to as Sind in contrast with Hind (the Gangetic plain and by extension northern India as a whole). Sind had been the first region in the sub-continent to come under Islamic rule with the Arab invasion in 92/711 and the ancient towns of Multan and Uch were both conquered by the ‘Umayyad general Muḥammad bin Qāsim. Multan was also among the first cities taken by Maḥmūd of Ghazni in the early fifth/eleventh century and subsequently remained a significant possession of the Ghurids and the Delhi Sultans. By the eighth/fourteenth century, therefore, Multan and Uch had been under Muslim domination for over six hundred years and had become significant centers of Islamic learning and culture. As the two most important cities of upper Sind, they served as the administrative and political centers for their regions, although Uch was sometimes politically and culturally dominated by Multan. Control of these territories was a ...