eBook - ePub

Living a Big War in a Small Place

Spartanburg, South Carolina, during the Confederacy

- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Living a Big War in a Small Place

Spartanburg, South Carolina, during the Confederacy

About this book

A history of life in one South Carolina city during the American Civil War, featuring personal stories from those who were there.

Most of what we know about how the Civil War affected life in the Confederacy is related to cities, troop movements, battles, and prominent political, economic, or military leaders. Far less is known about the people who lived in small Southern towns remote from marching armies or battles. Philip N. Racine explores life in one such place—Spartanburg, South Carolina—in an effort to reshape the contours of that great conflict.

By 1864 life in most of the Confederacy, but especially in rural towns, was characterized by scarcity, high prices, uncertainty, fear, and bad-tempered neighbors. Shortages of food were common. People lived with constant anxiety that a soldiering father or son would be killed or wounded. Taxes were high, inflation was rampant, good news was scarce and seemed to always be followed by bad. The slave population was growing restive as their masters' bad news was their good news. Army deserters were threatening lawlessness; accusations and vindictiveness colored the atmosphere and added to the anxiety, fear, and feeling of helplessness. Often people blamed their troubles on the Confederate government in faraway Richmond, Virginia.

Racine provides insight into these events through personal stories: the plight of a slave; the struggles of a war widow managing her husband's farm, ten slaves, and seven children; and the trauma of a lowcountry refugee's having to forfeit a wealthy, aristocratic way of life and being thrust into relative poverty and an alien social world. All were part of the complexity of wartime Spartanburg District.

"A well-written account that not only captures the plight of both the black and white population, but also offers some amazing cameos, especially the life of Emily Lyle Harris, who struggled to keep her large family in tact while her husband went off to war. This is a lively read and a perfect book to assign for classes covering the Carolina Upstate during the American Civil War." —Edmund L. Drago, professor of history, The College of Charleston, and author of Confederate Phoenix: Rebel Children and Their Families in South Carolina

" Living a Big War offers a fascinating, unflinching look at the toll the Civil War took on Spartanburg, clearly showing divisions that emerged and deftly employing stories of slaves, women, and other individuals to reveal the experiences of people on the home front." —Gaines M. Foster, dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Louisiana State University, and author of Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South, 1865–1913

Most of what we know about how the Civil War affected life in the Confederacy is related to cities, troop movements, battles, and prominent political, economic, or military leaders. Far less is known about the people who lived in small Southern towns remote from marching armies or battles. Philip N. Racine explores life in one such place—Spartanburg, South Carolina—in an effort to reshape the contours of that great conflict.

By 1864 life in most of the Confederacy, but especially in rural towns, was characterized by scarcity, high prices, uncertainty, fear, and bad-tempered neighbors. Shortages of food were common. People lived with constant anxiety that a soldiering father or son would be killed or wounded. Taxes were high, inflation was rampant, good news was scarce and seemed to always be followed by bad. The slave population was growing restive as their masters' bad news was their good news. Army deserters were threatening lawlessness; accusations and vindictiveness colored the atmosphere and added to the anxiety, fear, and feeling of helplessness. Often people blamed their troubles on the Confederate government in faraway Richmond, Virginia.

Racine provides insight into these events through personal stories: the plight of a slave; the struggles of a war widow managing her husband's farm, ten slaves, and seven children; and the trauma of a lowcountry refugee's having to forfeit a wealthy, aristocratic way of life and being thrust into relative poverty and an alien social world. All were part of the complexity of wartime Spartanburg District.

"A well-written account that not only captures the plight of both the black and white population, but also offers some amazing cameos, especially the life of Emily Lyle Harris, who struggled to keep her large family in tact while her husband went off to war. This is a lively read and a perfect book to assign for classes covering the Carolina Upstate during the American Civil War." —Edmund L. Drago, professor of history, The College of Charleston, and author of Confederate Phoenix: Rebel Children and Their Families in South Carolina

" Living a Big War offers a fascinating, unflinching look at the toll the Civil War took on Spartanburg, clearly showing divisions that emerged and deftly employing stories of slaves, women, and other individuals to reveal the experiences of people on the home front." —Gaines M. Foster, dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Louisiana State University, and author of Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause and the Emergence of the New South, 1865–1913

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE DISTRICT

PART ONE

People in Spartanburg District were in trouble. Life had become defined by scarcity, impossibly high prices, bad-tempered neighbors, and hard living. Many people were short on food. Salt, necessary to keep meat edible over time, was difficult to find and even then too expensive. Many lived in constant anxiety that a father or son off at war might be killed or wounded at any time. Often people blamed their troubles on their new government. Taxes were too high, everything cost too much and prices only seemed to get higher. What good news there was about the war seemed always to be followed by bad. The slave population was turning surly, and army deserters were threatening lawlessness—all creating fear. It seemed as if the new nation was on the brink of collapse, and leaders were asking for even more sacrifice, taxes, and fighting men, all resulting in more worry. How had such a good thing become so hard? How could their new nation, the Confederacy, and Spartanburg District survive? After starting off so well, so promising, so exciting, how had it all come to this?

1

The Setting

Located in the northwestern part of South Carolina among the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, Spartanburg District is made up of rolling hills drained by three river systems: the Pacolet, the Tyger, and along its most northeastern border with York District, the Broad. In the antebellum period half of the adjoining county of present day Cherokee was part of Spartanburg District. Dotted by shoals and in the dry season, shallows, none of the rivers is navigable to the coast. Since the latter part of the eighteenth century the upstate had the majority of the state's white population and a minority of its black population. Some of South Carolina's lowcountry districts had populations that were 80 percent slaves while its upcountry districts had populations that were typically about 30 percent slaves. By 1860, the lowcountry was dominated by plantations. Coastal areas grew rice and cotton (on the sea islands and up to thirty miles inland planters grew the long fiber, silky, “sea island cotton” and the rest of the area grew inland, short staple cotton) while the upcountry districts grew corn, other grains, and the short fibered cotton. In Spartanburg District 56 percent of the heads of households owned their own land and 44 percent were tenants; overwhelmingly they grew grains, especially corn, and only a few bales of cotton. Only about 30 percent of the heads of households owned slaves, and almost all of those households grew cotton.

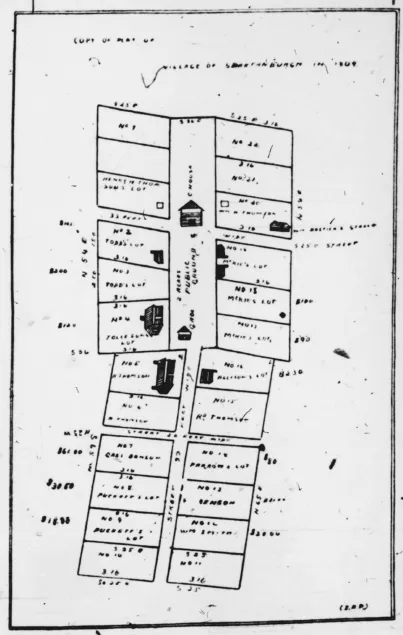

The center of the district was the city of Spartanburg. The city was more of a village. It had been laid out in 1787 on the Williamson plantation after its owner had sold the district a two-acre tract which contained a substantial spring.1 The layout of the buildings was centered around a large rectangle of vacant land, which, in 1881, would become known as Morgan Square—named for the statue of Daniel Morgan erected to celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of his victory at the Battle of Cowpens.

This 1809 drawing shows the rectangle of land around which Spartanburg village grew. Notice the jail on one end of the open space and the court house in the middle. Courtesy of Wofford College Library Archives.

At first the “square” was dominated by a jail on one end and a court house in the middle. By the 1860s, both had been removed; the court house (Spartanburg's third), was replaced in 1856 by an imposing structure with six two-story columns. Since 93 percent of the district's inhabitants were engaged in agriculture the village was small with one thousand to twelve hundred residents. In the mid 1850s, the Carolina Spartan, the village's newspaper, reported that the village consisted of “Thirteen dry-goods establishments; two saddler and harness establishments; two confectionary and druggist stores; one furniture room—any articles manufactured here; three carriage manufactories, five blacksmith shops; two shoe and boot making rooms; three tailoring establishments; three excellent hotels; three commodious churches, and another in progress of construction; two Academies, male and female; two day-schools for smaller pupils; lawyers and doctors a-plenty.”2

By 1860 there were some changes: now there were nine lawyers, nine surgeons and dentists, fifteen more merchants, one watchmaker, one brick mason, several wealthy farmers and one college for males—Wofford College, established in 1854.3 Spartanburg's business community grew little during the war. The Confederate government discouraged growing cotton, so agriculture stagnated. That same government bought up the production of the district's cotton mills, and other businesses had all they could handle supplying local demand. Many wealthy Confederates living elsewhere in the South late in the war nearly or actually bankrupted themselves by investing their fortunes in various Confederate bonds. It appears that the district's entrepreneurs did not as there was sufficient local capital after the war to promote and sustain a revived and expanded cotton mill building boom and a significant population increase in the city of Spartanburg.4

Built in 1850, the Palmetto House was one of three hotels in Spartanburg village during the Civil War. Photograph courtesy of the Herald-Journal Willis Collection, Spartanburg County Public Libraries.

As to industry and manufacturing in the rest of the district, the 1860 Industrial and Manufacturing Census reported forty-six grist and saw mills employing fifty hands, six tanning establishments employing thirty-eight hands, six cotton mills employing sixty-two male hands and seventy-four female hands (continuing a tradition which dated back to the first of Spartanburg's mills which preferred female hands as mill owners considered them more careful with the thread, less likely to break it, and less likely to create labor troubles), one iron foundry, and four cotton gins. All these enterprises were small and supplied little more than the local market. Ultimately, trade outside of the district was in cotton grown by a few plantations and large farms—owners of small farms who were lucky enough to grow one or two bales sold them to their more substantial neighbors who blended them into their own larger crops.

The district also had seven male academies with 284 students and eight teachers, and two female academies with fifty eight students taught by two teachers. The census also listed forty-eight “primary schools,” with a student population of 1,316 pupils taught by forty-eight teachers. The category “primary schools” probably included all the neighborhood, privately funded educational enterprises taught by tutors brought together by the individual efforts of farmers and businessmen. Year by year in their neighborhoods these people contracted with a teacher to instruct their children. David Harris, for instance, yearly tried to get up such a “school.” He was not always successful, and some years his wife Emily would take on the extra burden of instructing their daughters and sons. Even these “home schooling” efforts may have been included in the category “primary schools.”5 Also listed were two “Male High Schools” with ninety pupils and four teachers, and two “Female High Schools” with 165 pupils and eighteen teachers. The relationship between these schools, if such existed, is somewhat unclear, but it is clear that they received little in public funding. Each of the academies and the primary schools received fifty dollars a year. Clearly these were privately funded schools.

The district also had a number of churches dominated by the dissenting denominations. The census listed thirty-four Baptist churches with 19,350 members, twenty Methodist churches with 6,987 members, two Presbyterian churches with 1,100 members, and two Episcopal churches with 850 members. The membership for the Baptist churches seems high (over two thirds of the entire population or more than the entire white population). Perhaps that membership included slaves. Many slave owners allowed and even preferred their slaves to attend church services, sometimes with, but most often separate from, the white members. Slaves often had their own preachers. These services with an all African-American congregation required the presence of a white person lest the preacher engage in unacceptable rhetoric. Slaves often preferred Baptist and Methodist services as they were more emotional than those of other denominations. Whether the African-American congregates were counted in the census totals for Baptist and Methodist churches is unknown. If they were it would help account for the exceptionally high number given as Baptist congregates.6 In any case, the number was significantly exaggerated.

During the antebellum period, the politics of the district revolved around the Smith clan from the Southern part of the district. Its members were descendants of William Smith, who had served both as a United States Representative (1797–1799) and in the state senate (1801–1818). He had three sons, Isaac, John Winn who had his named changed to John Winsmith, and Elihu Penquite, all of whom served in the state house of representatives.7 Dr. John Winsmith and his brother Elihu continued to buy land and slaves throughout the antebellum period until they became some of the wealthiest of Spartanburg's planters. John Winsmith and John Zimmerman, both of whom lived in the Glenn Springs area, owned the most slaves in the district—just over one hundred each. A significant challenge confronted the Smith clan's dominance in the district over the nullification issue in 1832. Most of the opposition to nullification came from the upstate districts, especially Pickens, Greenville, York, and Spartanburg. Among the leaders of the opposition to nullification in Spartanburg was James Edward Henry, who arrived in South Carolina in 1816 and went on to become one of Spartanburg village's leading lawyers and politicians. Indeed, Henry was usually on the opposite side of most political issues from the Smith clan. In the 1830s, the majority of the residents of Spartanburg opposed the Smiths and nullification. Over the years, however, the increased activity of Northern abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates drove the inhabitants of Spartanburg District—and even Henry—toward secession.

By the late 1840s as pressure for secession grew, especially in the deep South, all factions in the district were moving in a radical direction. This was illustrated by the appearance of both Dr. Winsmith and James Henry on the same platform at a public rally on March 6, 1849, where Winsmith, who chaired the meeting, told his audience: “the question is now urged as one of political power, by which it is intended to make every interest of the South—her labor, and all her industrial pursuits, entirely subservient to Northern supremacy. Under this aspect of the case, all will agree that it is high time, this agitating question was settled…it must be met, and met now.”8 Henry also spoke at this meeting, and his remarks were well received. Some days later, in a letter to a friend, he gave some indication as to why he had been so welcomed: “Will your state stand up to your resolves? If so we shall have a Southern Confederacy. I have no doubt I am willing to take my share of the responsibility. I hope my ‘boys’ in case of fighting will be ready to do their duty…. In fact I am not exactly certain but what a dissolution of the Union would be the best thing that could happen to us.”9 A compromise worked out by Henry Clay avoided South Carolina's secession in 1850, but the differences between the sections were too great, the anti-slavery forces too determined, the slavery system too uncompromising, and the moral issue of slavery too explosive for peace to last.

During the Civil War political alliances tended to form around personalities. The Whig party had disappeared, and the vast majority of citizens were Democrats, but party played almost no role in political affairs. Issues were either distinctly local or centered around support for or in opposition to the administration of Jefferson Davis. Figures who had become prominent in the politics of the district and whose influence would remain during the war were B. F. Kilgore and B. B. Foster among the farmers; Gabriel Cannon and Joseph Finger, who had industrial interests in the district; and H. H. Thomson, Hosea J. Dean, James Farrow, D. C. Judd, Joseph Foster, Simpson Bobo and O. E. Edwards among the village dwellers.10 Residents of Spartanburg District elected the following delegates to the Secession Convention in December, 1860: John G. Landrum (Baptist minister), B. B. Foster (farmer), Benjamin F. Kilgore (physician-farmer), James H. Carlisle (professor of Mathematics at Wofford College), Simpson Bobo (lawyer) and William Curtis (Limestone Female High School president). Although a number of the district's inhabitants were unhappy with these proceedings, the overwhelming majority enthusiastically endorsed them.

Although the society of the district was generally egalitarian, there was no doubt that the wealthier farmers and townspeople were expected to lead, and so they did. Meta Grimball, an aristocratic refugee from the lowcountry, remarked on this seeming egalitarianism in the journal she kept during the Civil War.11 Except in unusual circumstances such as secession, people left those interested in politics to engage in them at will. Farmers who owned middling land and few slaves often interacted with owners of thousands of acres and many slaves. David Harris, for instance, who owned ten slaves and four hundred acres, went hunting with Dr. John Winsmith who owned more than fifteen hundred acres and over one hundred slaves.12 Most residents wished simply to be left alone and often showed remarkable apathy to the goings on in the district. Those persons, whether in the countryside or in the village, who seemed to have the most at stake when political decisions were made were happily obliged by the majority.

The entire state supported a slave economy. The lowcountry boasted its large plantations, with most having up to one hundred slaves, and many of the wealthy planters owned more than one plantation. The upcountry mainly consisted of small farms which typically had a smaller number of slaves (most often a slave family), and many farms with no slaves at all. Most upcountry people fervently supported slavery, for many upcountry, white, non-slave holders believed that the chief way to get ahead in the world was to acquire more land and obtain slaves. For many white people, the slave system was the bedrock of the greatest society the world had ever known, and many white people in South Carolina believed that any threat to the slave system was a threat to civilization itself.

Rural Spartanburg District was shattered by the Civil War. The relatively isolated area had a population of about twenty-eight thousand, about nine thousand of which were African Americans; Spartanburg village had about one thousand to twelve hundred inhabitants. The war years tested the mettle of these people, who were locked in a struggle that proved increasingly unpopular. After the Nullification controversy anti-slavery sympathies grew steadily in the rest of the nation (abolitionists were generally unpopular because of their insistence on the immediate eradication of slavery). After the nation acquired multiple territories in the West in the 1840s, Southern politicians became increasingly apprehensive over the issue of slavery's expansion into these newly acquired territories. This was a matter of principle more than reality, for few slave owners wished to move their slaves into what was then considered a desert. Southern politicians became exclusively defensive in their approach to national issues, and amidst this turmoil more residents of Spartanburg District mirrored their leaders and came to distrust the rest of the nation.

The major issue which overshadowed every other was slavery. From the 1830s on most of the white inhabitants of Spartanburg, both those who owned slaves and those who did not, grew increasingly defensive of their way of life. It appeared to them that the rest of the nation was determined to reduce the influence of their region and alter their institutions by ultimately abolishing slavery. This was ultimately symbolized in the second half of the 1850s by the rising strength of the Republican Party. In 1860, the election of a Republican president played a catalytic role in the secession of South Carolina from the Union. Defying the majority of their neighbors, some people in Spartanburg continued to reject secession as premature, unnecessary, and dangerous. Some Spartanburg residents were reluctant secessionists, primarily moved by public opinion. That reluctance would manifest itself in a myriad of ways during the coming war years. In the end, the war destroyed slavery, imperiled race control, and ultimately challenged the rural nature of life with an aggressive and voracious industrialism. The war profoundly shook the area's society. Spartanburg District was removed from the war's battles but not from its impact.

2

Spartanburg Wages War

Secession from the Union meant the independence long sought after by many of the men and women of Spartanburg District. Others in the area were ambivalent about the Union for many years prior to the 1850s. Leaders of the pro-Union factions in South Carolina were for the most part upcountry people, but during the decade of the 1850s political events hardened the attitudes of the people of Spartanburg into a strong distrust of the northern and western parts of the nation. Secession, which almost everyone in Spartanburg District strongly supported, engendered a feeling of triumph and a certainty that they were right. David Harris, an owner of ten slaves and a four hundred acre farm, wrote in his daily journal: “The members of Congress (Some of them) says South Carolina shall be shipped back into the Union. As she has declared her independence, I had rather see her blotted out of existence than to apply for admittance in the union again. Let her stay out if she perishes for it. Let her die rather than so humble herself.” Yet even before Fort Sumter made war certain, David had an uneasy feeling which lingered on behind his bravado: “As the certainty of war becomes more certain the fiery arder of the fighting men seems to cool off rapidly.” For those whose love of the Union had remained steadfast this was a time for a brief last hurrah. For a few days a group of Union men ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Part One: The District

- Part Two: Individuals

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Living a Big War in a Small Place by Philip N. Racine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.