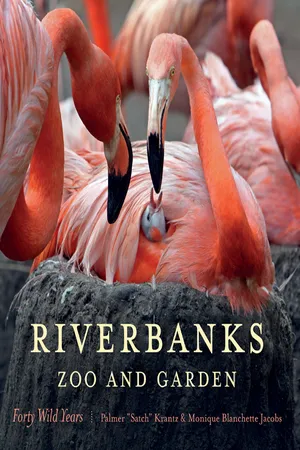

![]()

Chapter 1

THE EARLY YEARS

Contrary to popular belief, Riverbanks is neither Columbia’s first zoo nor its second. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Columbia actually had two zoos.

In 1897 the fifteen-acre Hyatt Park opened in Eau Claire, the city’s first suburban neighborhood. The park, developed by North Carolina–born Frederick H. Hyatt, featured a two-story pavilion, or “casino,” with a five-hundred-seat auditorium for vaudeville performances and concerts. It also boasted a café, soda fountain, shooting gallery and bowling alley. In addition the park was home to Columbia’s first zoo, housing an array of animals from a black bear, an alligator, rabbits, possums, porcupines, and deer to Japanese pheasants, an unknown species of bird referred to in various accounts as a “Mexican cockatoo,” ring-tailed and Java monkeys, lemurs, ocelots, and coyotes. Hyatt Park’s zoo operated until 1909. The pavilion continued to accommodate a handful of public events until it was demolished after World War I.

Four years later Irwin Park opened to the public on what is today the site of the city’s water treatment plant and Riverfront Park. The brain child of waterworks engineer John Irwin, the park is said to have been constructed by plant employees in their spare time. Along with a fountain, ponds, and a bandstand, the park featured a small zoo with swans, geese, ducks, owls, camels, deer, elk, ostriches, monkeys, bears, and goats.

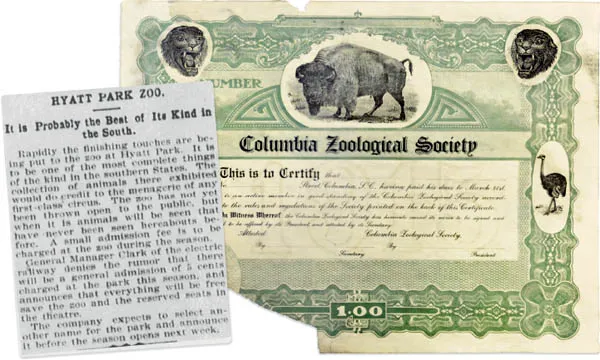

In hopes of demonstrating support for the Irwin Park Zoo, the first zoological society in Columbia was formed. By 1915 the society was offering lithographed membership certificates in exchange for annual dues of one dollar; a lifetime membership went for ten dollars. Animal donations were also accepted by the society. In the spring of that year, a local doctor told the press that he would consider donating a wild boar to the zoo, but only if the sign outside a Lady Amherst Pheasant display was removed because apparently the exhibit was occupied by a common crow.

(left) The State, May 5, 1901, p.8. (right) One of the original member certificates issued by the Columbia Zoological Society c. 1915

In 1916 several anecdotal stories appeared in the State. On February 24 one item reported that a new employee of the zoo, who was also an animal trainer with circus experience, intended to “train the animals in many smart things,” and he started out by taking on a wild cat with “serious objections to knowledge.” Another chronicled on October 12 that a North Carolina fruit farmer selling apples in Columbia had “hinted to the Irwin Park management” that he wanted them to take a four-hundred-pound bear named Mr. Bruin off his hands, “that is, of course, if the management is willing to pour a goodly number of dollars into the apple grower’s cart.” Another piece on December 30 recounted how a local businessman caught a six-foot rattlesnake, showed it off to all of his friends and customers, and then ultimately donated it to the zoo as a tribute to his own snakecatching skills.

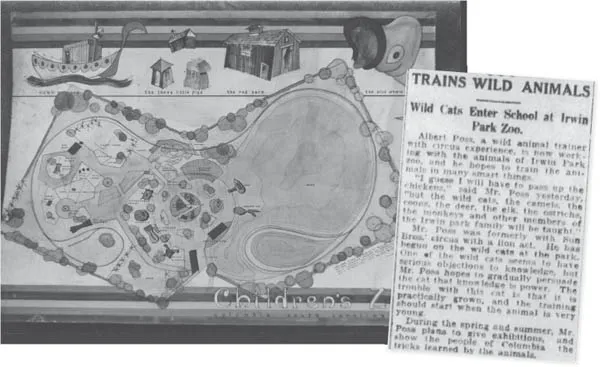

(left) The original concept for the Riverbanks Park was a children’s zoo featuring a storybook theme with exhibit names such as Noah’s Ark and Three Little Pigs. (right) The State, May 15, 1901, p. 9.

At the time Irwin Park was a refreshing addition to the community. A reminiscent piece in the Columbia Record dated May 9, 1946, claimed “it was almost the only public park in Columbia and the meeting place of the majority of the city’s children and nurses.” Irwin Park ultimately was dismantled during World War I because of the growing water demands by soldiers at Fort Jackson. Almost fifty years would pass before the citizens of Columbia could claim a zoo of their own.

Happy the Tiger remains a celebrity at Riverbanks. This bronze sculpture—a favorite family photo op—was donated by Stanley O. Smith, Jr., and his family in honor of the individuals and organizations whose early funding led to the development of Riverbanks.

Happy the Tiger

In 1964 Columbia, South Carolina, service-station owner O. Stanley (Stan) Smith bought a baby tiger. Unlike most exotic pet owners, he was not interested in having the most dangerous animal in town. Instead he wanted to promote his popular Gervais Street gas station and carwash. The service station was affiliated with Esso (now part of ExxonMobil), and the big oil company had just launched its famous “Put a Tiger in Your Tank” advertising campaign.

Smith purchased the two-week-old female tiger cub from Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo, at the time managed by legendary zoo director and TV personality Marlin Perkins. But Smith’s intentions were not entirely proprietary. He was also active in community affairs, especially with an initiative to develop a zoo for the children of Columbia. Efforts to build the zoo had so far failed, and interest seemed to be waning, so he hoped a live tiger would rekindle the public’s attention at a critical juncture. Smith also hoped that, in addition to driving gasoline sales and car washes, the tiger would serve as a living symbol for the future zoo.

Bamboo—Bambusa multiplex ‘Alphonso-Karrii’

COLOR: Yellow clumps with green striping

BLOOMING PERIOD: Grown for foliage

TYPE: Clumping Bamboo

SIZE: 15 to 20 feet tall

EXPOSURE: Full sun

People often cringe at the word “bamboo.” Riverbanks staff receive more calls from people wanting to rid their yard of bamboo than from people who want to plant the right kind. Bamboo does not need to be feared; clumping varieties such as ‘Alphonso-Karrii’ will not take over your yard (or your neighbor’s). This variety is especially nice for the color it adds to the garden with its yellow and green-striped canes.

Alphonso-Karrii boasts striped canes. Photograph by Matt Croxton.

The cub was soon housed in a replicated circus wagon parked against an outer wall of the carwash office. People flocked to see her, but there was a problem: the little tiger didn’t have a name. Ever the marketer, Smith held a city-wide naming contest, bringing even more publicity to his establishment. Competition was fierce; it seemed like everyone in Columbia wanted to name the community’s new four-legged celebrity. On March 8, 1965, a medical technician at Columbia’s VA hospital, Hattie Johns, was announced the winner with her submission “Happy the Tiger.” As part of the grand prize, Johns would have the honor of donating the tiger to the future zoo in her name.

Happy the Tiger was ultimately moved to the zoo and housed in one of a string of eleven glass-fronted exhibits in Small Mammal North (later renamed Riverbanks Conservation Outpost). She became known throughout South Carolina and, as Smith had hoped, helped provide the motivation needed to jumpstart efforts to develop the zoo-a zoo that would ultimately become one of the most successful in the United States. Happy died in 1979 at the age of fifteen. Smith commissioned a statue in her honor, which today can be seen just across from the original tiger exhibit at Riverbanks.

Columbia Zoological Society

In the early 1960s a prominent group of local business leaders, headed by Albert Heyward, formed the Columbia Zoological Society. Their goal was to develop a small children’s zoo just outside of the city-proper on the banks of the Saluda River. While little written documentation survives from their efforts, they were clearly instrumental in providing the spark that would soon ignite the creation of Riverbanks Zoo. Among the society’s most notable accomplishments was bringing to Columbia famed zoo director Marlin Perkins for advice on site selection. (It’s interesting to note that one of the sites identified was off Garners Ferry Rd. near the VA Hospital). The society also acquired sixteen acres of land along the Saluda River from South Carolina Electric and Gas and a small wood-framed house that would later serve as the zoo’s first administration building.

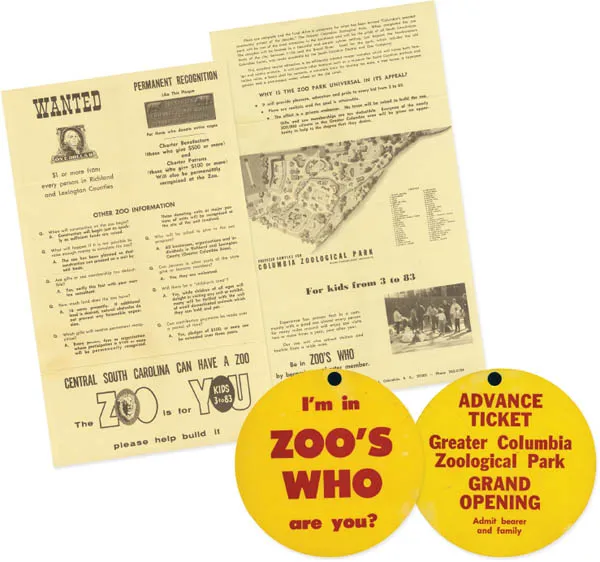

By 1965 an optimistic society had developed plans for a zoo that would cost between $300,000 and $350,000. The group proposed admission fees of 25 cents for adults and 10 cents for children, which based on their projected attendance, would generate about $24,000 in revenue each year. With this in mind, the society set out to raise money to build their zoo and launched a fundraising campaign called Zoo’s Who. In conjunction with donations received from the Columbia and Richland County Sertoma Clubs, the society ultimately raised around $60,000, far short of their $300,000 goal. The project fizzled after a few years because of a lack of funding, but the Columbia Zoological Society remained an active participant in the development of the zoo through the creation of the Riverbanks Park Commission in 1969. The group disbanded shortly thereafter, but their dream of a zoo for Columbia’s children served as the motivation behind all that followed.

In one of the first major fundraising efforts for the proposed zoo, schoolchildren went door-to-door seeking donations for the park. In exchange for contributions of one dollar, donors were issued a bright yellow “Zoo’s Who” tag, which served as an advance ticket to the grand opening of the zoo.

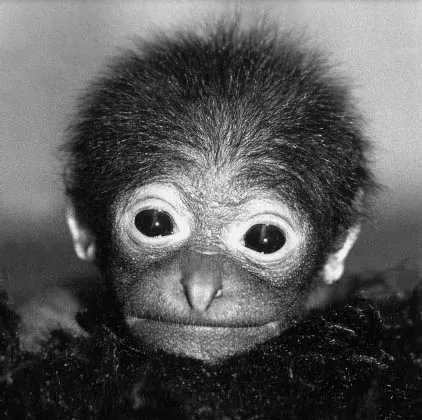

This baby siamang looks almost too cute to hoot and holler. Among the zoo’s most iconic animals are the howling monkeys, who are in fact not monkeys at all but siamangs—members of the ape family from Southeast Asia.

Riverfront Recreation

Columbia, South Carolina, sits at the confluence of two rivers—the Broad and Saluda—that on meeting form the Congaree River. In essence Columbia was a planned city, having been selected by the state legislature in 1786 to be the site of South Carolina’s new capital because of its centralized location. From the city’s inception, the riverfront area was considered undesirable, since it housed warehouses, wharfs, taverns, and more than one house of ill repute, and for much of the twentieth century Columbia’s riverfront property remained largely inaccessible and undeveloped, a tangle of abandoned buildings, vines, and thick undergrowth.

But in the mid-1960s a group of area business leaders set out to change this dynamic as they set their sights on developing an extensive park on a beautiful 500-acre tract of land on either side of the Saluda River, less than a mile from downtown. They hoped the park, which they initially envisioned as a historic theme park, would breathe life into Columbia’s meager tourism industry by turning their sleepy little city into a must-stop destination for people driving between the Northeast and Florida. This, however, would be no easy task. The next several years ...