- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Mobile River

About this book

"A fine, fascinating book. John S. Sledge introduces us to four centuries worth of heroes and rogues on one incredible American river." —Winston Groom,

New York Times–bestselling author of

Forrest Gump

The Mobile River presents the first-ever narrative history of this important American watercourse. Inspired by the venerable Rivers of America series, John S. Sledge weaves chronological and thematic elements with personal experiences and more than sixty color and black-and-white images for a rich and rewarding read.

Previous historians have paid copious attention to the other rivers that make up the Mobile's basin, but the namesake stream along with its majestic delta and beautiful bay have been strangely neglected. In an attempt to redress the imbalance, Sledge launches this book with a first-person river tour by "haul-ass boat." Along the way he highlights the four diverse personalities of this short stream—upland hardwood forest, upper swamp, lower swamp, and harbor.

In the historical saga that follows, readers learn about colonial forts, international treaties, bloody massacres, and thundering naval battles, as well as what the Mobile River's inhabitants ate and how they dressed through time. A barge load of colorful characters is introduced, including Native American warriors, French diplomats, British cartographers, Spanish tavern keepers, Creole women, steamboat captains, African slaves, Civil War generals and admirals, Apache prisoners, hydraulic engineers, stevedores, banana importers, Rosie Riveters, and even a few river rats subsisting off the grid—all of them actors in a uniquely American pageant of conflict, struggle, and endless opportunity along a river that gave a city its name.

"Sledge brilliantly explores the myriad ways human history has entwined with the Mobile River." —Gregory A. Waselkov, author of A Conquering Spirit

The Mobile River presents the first-ever narrative history of this important American watercourse. Inspired by the venerable Rivers of America series, John S. Sledge weaves chronological and thematic elements with personal experiences and more than sixty color and black-and-white images for a rich and rewarding read.

Previous historians have paid copious attention to the other rivers that make up the Mobile's basin, but the namesake stream along with its majestic delta and beautiful bay have been strangely neglected. In an attempt to redress the imbalance, Sledge launches this book with a first-person river tour by "haul-ass boat." Along the way he highlights the four diverse personalities of this short stream—upland hardwood forest, upper swamp, lower swamp, and harbor.

In the historical saga that follows, readers learn about colonial forts, international treaties, bloody massacres, and thundering naval battles, as well as what the Mobile River's inhabitants ate and how they dressed through time. A barge load of colorful characters is introduced, including Native American warriors, French diplomats, British cartographers, Spanish tavern keepers, Creole women, steamboat captains, African slaves, Civil War generals and admirals, Apache prisoners, hydraulic engineers, stevedores, banana importers, Rosie Riveters, and even a few river rats subsisting off the grid—all of them actors in a uniquely American pageant of conflict, struggle, and endless opportunity along a river that gave a city its name.

"Sledge brilliantly explores the myriad ways human history has entwined with the Mobile River." —Gregory A. Waselkov, author of A Conquering Spirit

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

COMING AHEAD

1

Indian Stream to

Entrada Española

Tantalizing archaeological discoveries not far from the delta, such as a beautiful fluted Clovis spear point found along the lower Tombigbee River, indicate that human beings were present in southern Alabama many thousands of years ago. They were nomadic hunters and gatherers, descendants of those hardy Siberians who first crossed the land bridge into North America during the last ice age. It is almost certain that they ranged the gentle river valley that is now Mobile Bay and the coastal woodlands that are now inundated by gulf waters far offshore, but for obvious reasons hard evidence is lacking.1

Concrete and much more extensive evidence of human habitation along Mobile River and Bay becomes available for the period beginning about three thousand years ago, when area shorelines had essentially assumed their present configurations. Archaeologists refer to this as the Woodland Period, characterized by more-settled living; a practical mix of hunting deer, small game and birds, gathering nuts and berries, limited agricultural efforts, and exploitation of such estuarine food resources as oysters, clams, and fish; the construction of burial mounds; and the use of sand or fiber tempered pottery to bind the clay and prevent cracking.2 Woodland peoples were thoroughly at home in their world and adept at utilizing everything in it to enhance survival. Nothing was wasted, and in the benign climate their numbers increased.

Numerous Woodland sites have been identified and dug in the Mobile River delta, providing valuable insight into that distant era. At least three were mapped and briefly investigated during a cultural resources survey of the area during the early 1990s. As simple as these sites are, they provide a useful window into Woodland ways. The first is located on the west bank of Bayou Sara and consists of a small shell midden—or, crudely put, a trash heap. At the time of the dig the midden was roughly nine feet wide by fifteen feet long, just over seven inches high, and steadily eroding into the bayou. Despite these modest dimensions and the instability of the site, a simple shovel test unearthed a fascinating range of artifacts including a deer bone, marsh clam shells, some burned bones, wood fragments, and several sand-tempered potsherds. The site would appear to have been a campsite, occupied for a limited time, where the native people hunted, harvested shellfish, and then cleaned, cooked, and ate their game.3 From these fragments one can easily imagine what these Indians’ life would have been like at this place. Everyone in the group—men, women, and children—participated in hunting and gathering food. Men ventured far afield for large game such as dear and bear for days at a time. Women and children hunted the immediate surrounds for smaller game, perhaps using snares. And everyone harvested the rich waters around them, net-fishing and easily scooping clams out of the brackish shallows and quickly heating them on little wooden grills over small fires. When the men returned from long hunts, there must have been hearty greetings—if they were lucky that is—and people would have turned to butchering and skinning the partially cleaned animals so that some meat could be eaten on the spot, more smoked and hung on strings from house rafters for later, and the hides and bones worked into multifarious utilitarian items such as pouches, moccasins, scrapers, and awls. No doubt much of these people’s time was occupied with the getting and preparation of their meals, and when they finished eating they flung the refuse onto the ground to be unearthed by future archaeologists.

The second site is submerged beneath Chuckfee Bay, to the east of Twelve Mile Island and the Mobile’s main channel, but originally it would have been above water. The archaeologists reported a badly eroded midden composed mostly of clam shells, with large amounts of pottery scattered around the feature and across the bay bottom. The sherds they recovered were plain or simply decorated and sand tempered, typical of the Woodland Period. They also found part of a turtle shell and fragments of mammal bones. As with the Bayou Sara midden, these items indicate that the Indians enjoyed a variety of readily obtainable foods in their diet, and ceramic vessels were critical to preparing, eating, and storing them. The fact that the site is underwater also provokes intriguing thoughts about how many other early archaeological sites might be flooded and lie yet undiscovered beneath the area’s rivers, streams, bayous, and bays.4

The third site is on the west bank of Big Briar Creek, east of the Mobile’s main channel. It includes a large shell midden eroding into the water, which shovel tests showed to include hundreds of clam shells, as well as turtle, mammal, and bird bones. But the most exciting discovery was a partial human skeleton, including numerous teeth, a right femur, an arm bone, and a shoulder blade. Analysis showed them to belong to an individual well-formed adult male. Though later material was found at the site, because of the type of pottery associated with the skeleton, it is believed to date to the middle Woodland Period. If so, its degree of development further confirms that the Mobile delta’s early human inhabitants were well fed and strong.5

Woodland customs persisted until about a thousand years ago, when the more sophisticated Mississippian Period began. Lasting roughly until the Spanish entradas of the sixteenth century, this period was characterized by large-scale mound building; elaborate religious ceremony and ritual; better and more decorative pottery; widespread cultivation of beans, maize, pumpkins, and squash; athletic games; extended trade routes; larger towns grouped into chiefdoms; use of the bow and arrow; and more warfare.6

One of the gulf rim’s most important Mississippian chiefdoms was centered in the Mobile delta on what is called Mound Island, not far from the Tensaw and Middle Rivers. Accessible only by boat via a small stream known as Bottle Creek, the site is an astonishing complex of eighteen earthen mounds, the tallest of which is forty-five-feet high. Since it is heavily grown over now with towering trees and large palmettos that spread their broad fans at eye level, it is difficult to fully appreciate what this place would have been like during its prime Indian occupation seven hundred years ago.

Happily, due to the efforts of many archaeologists and researchers down the decades, a fairly plausible sense of the Bottle Creek site’s significance and original appearance can be pieced together. It served as the ceremonial capital of what archaeologists call, somewhat confusedly for the layperson, the Pensacola Chiefdom. They chose this term because of so many associated sites clustered around that city and the general environs, but the Pensacola Chiefdom’s influence stretched along the coast in both directions and up the Mobile River system as far as present-day Selma. The people who established this chiefdom had strong ties with the Indians at Moundville to the north and in the Lower Mississippi Valley to the west, and might have even represented a colonization effort of sorts. Given the Pensacola Chiefdom’s access to the rich resources of the Mobile Bay Delta, it is easy to see why inland chiefdoms would value its friendship, no doubt making for a wide trade web. In this scenario these Mississippian Indians would have moved into the area, dominating and absorbing the resident Woodland Indians and creating the Pensacola Chiefdom.7

Certainly the construction of all those mounds required a high level of social organization and control. They were erected by basketfuls of earth transported from nearby borrow pits and when completed were topped with structures that were occupied by the chiefdom’s religious and secular leaders. These structures, now long deteriorated away, had timber posts set into the ground, walls of river cane and mud, and roofs of palmetto fronds. From their lofty platforms the nobles would have looked over a large cleared plaza surrounded by the smaller mounds and earthworks, some of which contained burials. Besides enjoying a better view than their people, the leaders also got better food. In digging the top of the largest mound, archaeologists discovered evidence of superior cuts of meat, plenty of corn, and bigger oysters and clams than those found below. Also, the number of serving vessels recovered indicates that the ruling nobles were well tended by servants or slaves.8

Ensconced in the middle of this watery world, the Pensacola Chiefdom depended on good boats to exert its influence, conduct trade, and just manage the day-to-day realities of life in such a place. Like early people elsewhere, these Indians became practiced at fashioning safe and effective dugout canoes. Their construction methods likely did not change much over the centuries, and the observations of Captain Bossu regarding the making of such a canoe in the 1750s by Mobile Indians would obtain for the residents of the Bottle Creek site as well. According to Bossu, the Indians first selected a good tree of the right girth, usually cypress, and then set fire to it. After it fell they laid it on a frame, crudely shaped it, and again used fire along its length after which, he wrote, “they scraped away the live coals with a flint or an arrow.” Wet mud might have been used along the sides of the log to control the fire and extensive working with stone and shell tools ultimately produced a sleek and swift river-worthy craft. Some have even been found in Florida with holes drilled into the bow for securing a line. Bossu noted that these canoes were used both for war and for carrying furs, and that the Indians were “very skilled in conducting these little vessels upon their lakes and rivers.”9

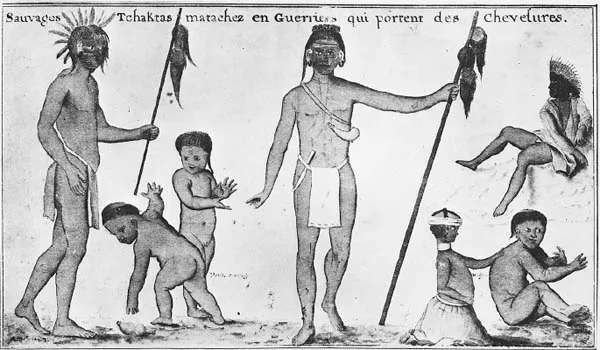

What did these Indians looks like? According to the archaeology as well as later descriptions by the Spanish and the French, they were “well made both men and women,” with coppery skin and long black hair. In a strange custom some had flattened foreheads that were the result of being strapped to cradle boards in infancy. This feature was thought to be highly attractive in their culture. Elaborate tattoos were common, sometimes in great whorls, and necklaces and earrings were worn by the more important. Copper and pearl adornments were also popular, but these Indians did not possess any gold, as the Spaniards would soon discover to their keen disappointment. Clothing varied by season and social class. During the warm months men and women went mostly naked, with only loincloths or, in the case of the women, Spanish moss, to cover their sex. In colder weather, deer or other animal skins and feather capes provided effective comfort. Chiefs, such as that of the Coosa encountered by Hernando de Soto in 1540, were sometimes quite impressively attired in beautiful robes or capes, with ornate headdresses.10

Warfare was a brisk and brutal business, with the enemy usually dispatched by arrow or club. Scalping was routine. Pitched battles between equal numbers of combatants would have been rare. Ambush or surprise was preferred. Captives were triumphantly paraded back to the home village and either put to work or, if they were important warriors, tortured and killed. Indian torture was a ghastly practice that made many Europeans shudder, but it is not exactly clear how much the Indians were influenced by the Spanish in their techniques, especially the burning or roasting prisoners alive. This was a common punishment during the Inquisition in Europe and no doubt was used on the Indians as well by Soto and possibly others. Sometimes a captive was simply made to kneel and had his brains dashed out by a heavy war club. The more unlucky were stripped, tied to a post, and prodded with sticks, weapons, and burning brands. Indian women, especially those who had lost relatives to warfare, were enthusiastic participants in the proceedings. The prisoner’s ears and nose were cut off, his hair scalped, hot coals placed on his head and held down with mud, and his skin gashed. If the victim cried out or was obviously afraid, the punishment was delightedly redoubled. He was expected to bear up, sing a war song, taunt his enemies, and mock the efforts to inflict pain. The end result was always the same, of course, but the warrior’s demeanor and pride were everything.11

Choctaw Indians. The black child with the strange headgear was probably taken in a raid. Courtesy of the History Museum of Mobile.

Whether or not anyone was tortured on Bottle Creek’s plaza is unknown, though the French encountered the practice among the area’s Indians when they arrived much later. There can be little doubt that the plaza hosted games, dances, and ceremonies related to the chiefdom’s agricultural calendar. Among the most important of these would have been a green corn ceremony, or busk, to greet the ripening crop in high summer. The Pensacola Chiefdom included numerous small farming villages, and crops were extensively cultivated on the delta’s low ground, where regular flooding continually renourished the soil. The success of these crops was crucial to the people’s survival, and a good year meant plenty. In celebration there would have been fasting, dancing, and games such as chunkey. This sport was played in an open smooth area, like the plaza, in front of numerous onlookers—some perhaps even betting on the outcome. The action consisted of rolling a disk-shaped stone and having warriors throw spears at it in an attempt to come the closest. Team sports including ball, which was in reality a distant cousin of lacrosse, were also popular and frequently violent. One nineteenth-century account describes a player killed outright on the field, three badly hurt who died later, and more than a dozen who took better than a month to recover. Chiefdoms likely competed against one another, with the losers being deeply shamed. The Indians considered such competition “the little brother of war,” and it held great importance within their culture.12

In their spiritual life these Indians worshipped the sun, and fire was also important to them. In the early eighteenth century a Frenchman reported that the Natchez Indians kept a perpetual fire burning in their temple. “They say this fire represents the sun,” he wrote, “which they worship.”13 It is probable that Bottle Creek harbored such a flame as well, closely attended and maintained atop one of the mounds. The Indians also paid close attention to celestial events, knew how to read the weather—vitally important in hurricane country—and told stories to explain their origins and various aspects of the natural world. They were curious about strangers, if nonthreatening, and that is probably how they initially reacted when oddly dressed white men in an unusual watercraft appeared in the large bay at their doorstep.

Who were they, those first white men? If legend is to be credited, they were a ragtag company of medieval Welshmen led by their prince, Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd, fleeing bloody civil war at home. The old poets mention him and his great voyage but provide no details of his route. Nonetheless, during the sixteenth century the English found the legend useful in reinforcing their New World claims, and during the nineteenth century American intellectuals marveled over unusual ruins in the mid-South and seemingly credible stories of Welsh-speaking Indians. They connected these to the Madoc legend. In a letter dated October 9, 1810, former Tennessee governor John Sevier described an interview he had conducted with an old Cherokee chief almost thirty years earlier. Sevier asked the chief about the origins of some castlelike fortifications and was told they were made by “the White people who had formerly inhabited the country now called Carolina.” When asked who these mysterious white people were, the chief told the governor, “they were a people called Welsh, and . . . they had crossed the Great Water and landed first near the mouth of the Alabama River near Mobile and had been driven up to the heads of the waters.”14

It is indeed romantic to think of a small wooden ship, much battered by the elements, moving up the Mobile River with her salt-stained sail hanging limply while her crew labors at their oars. The men’s grunts and the steady bump of their wooden sweeps against rusted iron oarlocks the only sounds in an awesome new green world, as dark eyes wonderingly stare at them from deep in the river cane. Could this possibly have been? Might the Mobile’s uncommunicative mud yet yield a jeweled brooch or an iron shield boss dating to the twelfth century? No reputable historian believes so. But there is always the possibility. One of the most distinguished scholars of Gulf Coast history once tackled the subject, and in the end pronounced Madoc “as elusive as a seawraith.”15 ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: Downriver with Cap’n Joe

- Introduction: “A fine, large river”

- Part 1. Coming Ahead

- Part 2. Currents

- Epilogue: Elegy for a Small Shipyard

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Mobile River by John S. Sledge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Historical Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.