![]()

[ PART 1 ]

Rhetoric Revealed

![]()

Should We Name the Tools?

Concealing and Revealing the Art of Rhetoric

CAROLYN R. MILLER

“Socrates: My accusers…told you that you must be careful not to let me deceive you—the implication being that I am a skillful speaker. I thought that it was peculiarly brazen of them to tell you this without a blush, since they must know that they will soon be effectively confuted, when it becomes obvious that I have not the slightest skill as a speaker—unless, of course, by a skillful speaker they mean one who speaks the truth.”1

Throughout its troubled history, two opposing impulses have persisted within rhetoric, an impulse toward self-aggrandizement and another toward self-denial. Plato's Gorgias announces grandly that rhetoric is “the greatest boon, for it brings freedom to mankind in general and to each man dominion over others.”2 Cicero's Crassus claims that “in every free nation, and most of all in communities which have attained the enjoyment of peace and tranquillity, [eloquence] has always flourished above the rest and ever reigned supreme.”3 This one art, he says, has the ability “to raise up those that are cast down, to bestow security, to set free from peril, to maintain men in their civil rights.”4 And rhetoric is not only powerful, it is ubiquitous; it can speak on any subject: as Plato's Gorgias claims, “rhetoric includes practically all other faculties under her control.”5 Thus rhetoric vaunts itself, both in the academy and in the public sphere.

Such self-aggrandizement is not unfamiliar to contemporary minds, as rhetoric has experienced a disciplinary and intellectual renaissance, with journals and books, curricula and symposia, devoted to its power and ubiquity. We have said that rhetoric is “epistemic,” that it affects the conduct of inquiry and the substance of knowledge across the disciplines. We have committed ourselves to using the powers of rhetoric to meet challenges in the public realm, challenges to social justice, democratic process, public responsibility, and civility. Kenneth Burke, in an anaphoric, epanaleptic aphorism we love to quote, told us that “wherever there is persuasion there is rhetoric. And wherever there is ‘meaning' there is ‘persuasion.'”6 Rhetoric's imperialism has reached such a pitch recently that critical alarms have been sounded, urging “attenuations” of its epistemic claims and challenging its ambitions as a “universalized,” “promiscuous,” “free-floating,” “interpretive metadiscourse.”7

Criticism like this helps to counter rhetoric's grand ambitions, but there is another countervailing force, and that is rhetoric's own enduring impulse toward self-denial. Here, rhetoric seeks not to “flourish” or to “reign,” but to disappear, to get out of the way, possibly even to admit to being “mere rhetoric.” The motto for this impulse is that the art of rhetoric lies in concealing the art: ars est artem celare.8 Rhetorical treatises, beginning at least with Aristotle, point out the need for rhetorical artifice and strategy to remain hidden: “authors should compose without being noticed and should seem to speak not artificially but naturally. (The latter is persuasive, the former the opposite.)”9 George Kennedy calls this passage “perhaps the earliest statement in criticism that the greatest art is to disguise art.”10 In De Inventione, Cicero noted that brilliance and vivacity of style “can give rise to a suspicion of preparation and excessive ingenuity. As a result of this most of the speech loses conviction and the speaker, authority.”11 Quintilian put the matter plainly: “if an orator does command a certain art…, its highest expression will be in the concealment of its existence.”12

Rhetoric, it seems, must deny itself to succeed. Michael Cahn has called this rule “the very heart of rhetoric,” right from its beginning.13 The principle has become embedded in the tradition, a commonplace passed along and kept alive by writers who include Puttenham, La Rochefoucauld, Butler, Swift, Pope, Burke, Rousseau, and Wilde. The principle is modeled for the Renaissance in Castiglione's concept of sprezzatura, glossed by Richard Lanham as a “rehearsed spontaneity” and described by Castiglione himself as a capacity ensuring that “art is hidden and whatever is said and done seems without effort or forethought.”14 Sprezzatura is celebrated in the English Renaissance from Herrick to Sidney to Shakespeare.15 Another Renaissance figure who serves for us as the paragon of dissimulation is Machiavelli, who advises the prince that because it is sometimes necessary to do evil, it is also necessary to dissimulate, to construct what we might now call “plausible deniability,” so that “everyone sees what you appear to be, [but] few know what you really are.”16 But the principle of rhetorical concealment is more than the everyday dissimulation of intentions: it is the conviction that the means by which intentions are concealed must also remain undetectable; in other words, we must be convinced that no dissimulation is going on; it is a dissimulation of means as much as of ends. Thus, if “all a rhetorician's rules / Teach nothing but to name his tools,” it is best if the tools—and their names—remain under wraps when Sir Hudibras sallies forth.

According to Cahn, rhetoric is the only art with this tradition of self-denial, the one art that “has to live with the requirement of concealing its achievement in order to attain recognition.”17 Indeed, the ancient arts that were often compared with rhetoric, such as medicine, cookery, flute-playing, navigation, and gymnastics, do not seem to have much to hide, and neither do such contemporary arts as engineering or architecture. We can use and appreciate their products or results even if we happen know a great deal about how they are produced, what materials, ingredients, processes, and techniques go into their success. But other arts are different, and these are used by Plato in a series of complex comparisons and classifications that suggest rhetoric's affinity with arts such as cosmetics, seduction, enchantment, hunting, and military strategy.18 Here the story is different, suggesting that Cahn may not be correct about rhetoric's unique need for concealment. Cosmetics, for example, part of Socrates' elaborate comparison of the sham arts and the true arts in the Gorgias, would seem to require concealment.19 Like theatrical illusion, the effect of the cosmetic art dissipates the more we know about its part in the creation of beauty. We admire the skill involved in exercising the art rather than the appearance of the wearer, the art itself rather than its results.

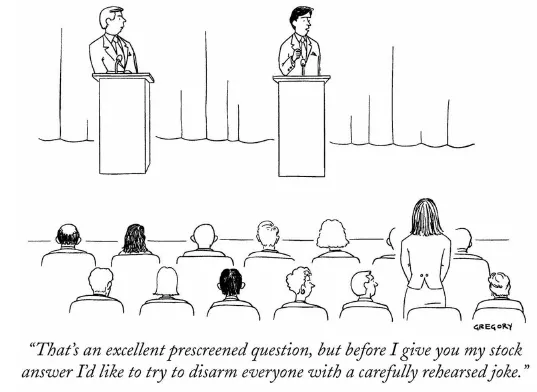

If dissimulation and concealment are indeed necessary for rhetorical success, we face a number of problems as we contemplate both the public work of rhetoric and the educational role of rhetoric. If rhetoric can be more effective, more useful, more powerful, if it remains concealed, what can it mean for rhetoric to go public? What can its “public work” be? Is there a self-defeating premise built into the educational project? Or an entailment of ever more widespread cynicism? If, through the sustained rhetorical education and public acceptance we seek, rhetoric is indeed revealed as a Gorgianic power available to everyone, will public discourse or our social conditions actually improve? The dilemma that intrigues me is epitomized in a New Yorker cartoon, where the public work of rhetoric is unconcealed by naming the tools.

In this essay, I spend some time exploring the principle of concealment in more detail, drawing primarily on the multiple ways that it is expressed in the classical tradition, because the ancients were astute observers of the workings of rhetorical power, particularly in the public realm. I examine these sources for what they can reveal about the justifications for and consequences of concealment. The sources give some clues to the conditions in which rhetoric must work and thus the possibilities for its public role. And I close with some observations about what these conditions mean for the relationship between rhetoric's public work and rhetoric's role in the education of citizens for that work.

The classical sources are suffused with observations and advice about the necessity for concealment.20 They reveal a series of recurring themes that justify the need to conceal the art of rhetoric. These themes seem to derive from two foundational assumptions that are fully naturalized in our understandings of how humans use language: an adversarial model of human relations and a mimetic model of language.

© The New Yorker Collection 2000. Alex Gregory from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved

HUMAN RELATIONS ARE ADVERSARIAL

1. The dominant and most frequent theme is one I call suspicion. This theme appears in the passage by Aristotle quoted earlier: artifice is not persuasive, because it makes people suspect “someone plotting against them.”21 We treat the intentions of others as plots against us in a zero-sum game: if you win, I lose. You are likely to be trying to cheat me out of something, to deceive me, so I must be suspicious. Athenian suspicion was embedded into a law against deceiving the democracy, a law justified in Demosthenes' statement to the assembly that “A man can do you no greater injustice than telling lies; for, where the political constitution is based on speeches/words, how can it be safely administered if the words/speeches are false?”22

Two examples from the advice about concealment suggest how pervasive the theme of suspicion is in the classical tradition:

There is an inevitable suspicion attaching to the unconscionable use of figures. It gives a suggestion of treachery, craft, fallacy, especially when your speech is addressed to a judge with absolute authority.…So we find that a figure is always most effective when it conceals the very fact of its being a figure.23

Care must be taken to avoid exciting any suspicion in this portion of our speech, and we should therefore give no hint of elaboration in the exordium, since any art that the orator may employ at this point seems to be directed solely at the judge.24

2. The second theme, spontaneity, identifies the notion that statements we can trust are those that come easily and naturally; conversely, a premeditated statement, one that is obviously crafted and constructed beforehand, deserves our suspicion. For example, the Rhetorica Ad Herennium cautions about the use of certain figures involving word-play: “[such figures] are to be used very sparingly when we speak in an actual cause, because their invention seems impossible without labour and pains.”25 The principle of spontaneity presupposes that dissimulation requires more preparation and effort than telling the truth—it requires precisely the effort of concealment. Spontaneity thus serves as a kind of guarantee that no concealment can have occurred and is thus generally understood as a sign of truth or credibility. Here, for example, is Longinus again: “For emotion is always more telling when it seems not to be premeditated by the speaker but to be born of the moment; and this way of questioning and answering one's self counterfeits spontaneous emotion.”26

But note the “seems” in the quotation and the possibility of counterfeit emotion. Spontaneity itself can be an effect created with no less labor than highly figured speeches, as Cicero makes clear in this passage about the orator Antonius: “His memory was perfect, there was no suggestion of previous rehearsal; he always gave the appearance of coming forward to speak without preparation, but so well prepared was he that when he spoke it was the court rather that often seemed ill prepared to maintain its guard.”27

In On the Sophists, Alcidamas suggests that “the style of extemporaneous speakers” is most effective and can be imitated. Quintilian also concedes that spontaneity may be artificial: “Above all it is necessary to conceal the care expended upon it [artistic structure] so that our rhythms may seem to possess a spontaneous flow, not to have been the result of elaborate search or compulsion.”28

3. Closely related to spontaneity is the theme of sincerity. Spontaneity affects the trustworthiness of statements, and sincerity affects our trust in the speaker; in this way spontaneity produces sincerity (or, to be more precise, the impression of spontaneity produces an impression of sincerity).29 Here is Quintilian, for example: “Who will endure the orator who expresses his anger, his sorrow or his entreaties in neat antitheses, balanced cadences and exact correspondences? Too much care for our words under such circumstances weakens the impression of emotional sincerity, and wherever the orator displays his art unveiled, the hearer says, ‘The truth is not in him.'”30

Similarly, the Rhetorica Ad Herennium cautions that “we must take care that the Summary should not be carried back to the Introduction or the Statement of Facts. Otherwise the speech will appear to have been fabricated and devised with elaborate pains to as to demonstrate the speaker's skill, advertise his wit, and display his memory.”31

The sincere speaker says what he or she really believes, which should require no effort, and is more interested in the truth than in persuasive influence. Such a speaker treats communicative relations as cooperative rather than adversarial, or perhaps as though they were cooperative rather than adversarial. But cooperation itself may be a disarming strategy, a distraction, a way of concealing adversarial intentions.

The themes of suspicion, spontaneity, and sincerity reinforce each other and together presuppose deeply adversarial communicative relationships, as illustrated in this formulation by Alcidamas: The truth is that speeches that have been laboriously worked out with elaborate diction (compositions more akin to poetry than prose) are deficient in spontaneity and truth, and, since they give the impression of a mechanical artificiality and labored insincerity, they inspire an audience with distrust and ill-will.32

Adversarial relationships figure prominently in Plato's classification of the arts, mentioned earlier. He classifies rhetoric with the combative, acquisitive, or conquering arts, such as boxing, wrestling, hunting, and military strategy.33 The comparison of rhetoric to these arts is endemic to the entire classical tradition. In such competitive endeavors, knowledge of the opponent's art makes it less effective, reducing surprise and enabling countermaneuvers. The hunter and the ...