![]()

CHAPTER ONE

ATLANTA

New South Brilliance Ascending from Embers of Civil War

FIG. 4. Atlanta Skyline, ca. 2010. Wikimedia Commons, OTRS System Archives.

On December 22, 1886, when the eloquent Henry Woodfin Grady (1850–1889), innovative managing editor of the Atlanta Constitution, presented his impassioned speech championing “The New South,” Atlanta had only recently established a viable industrial complex.1 Moreover, the city had merely a small, unofficial artists’ colony, formed long after Charleston’s and New Orleans’s organized art associations.

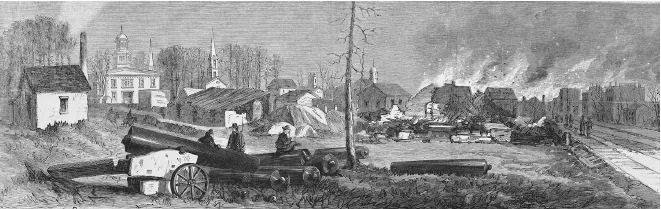

A significant hindrance to Atlanta’s early urban art alliance was its date of incorporation: 1847, a century and a half after Charleston was settled and some forty years after New Orleans was established. The other compelling hurdle was the Civil War. Many in the city, especially businessmen, opposed secession; but when the Civil War began, Atlanta became an axis of the Confederacy. Illustrators and photographers (such as George N. Barnard, hired by Sherman) were employed by the army or periodicals during the conflict (figs. 5 and 6); yet little effort was made in the organization of art in the midst of an embattled city.

FIG. 5. George N. Barnard, Atlanta, Before being Burnt by the Order of Gen. Sherman, from the Cupola of the Female Seminary, 1864. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

FIG. 6. Destruction of the Depots, Public Buildings, and Manufactories at Atlanta, Georgia, November 15, 1864. From Harper’s Weekly, January 7, 1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Sherman issued a mandatory evacuation before burning and devastating Atlanta. He wrote to Mayor James M. Calhoun (whose father was a cousin of John C. Calhoun): “I cannot discuss this subject with you fairly, because I cannot impart to you what we propose to do, but I assert that our military plans make it necessary for the inhabitants to go away, and I can only renew my offer of services to make their exodus in any direction as easy and comfortable as possible. . . . We don’t want your negroes, or your horses, or your houses, or your lands, or any thing you have, but we do want and will have a just obedience to the laws of the United States . . . and, if it involves the destruction of your improvements, we cannot help it.”2

After the wreckage hordes of detested Yankee soldiers invaded Atlanta, pillaging what homes were spared and breaking apart what they could not steal. Yet as early as 1865, Mayor Calhoun proposed a rapid restoration of commercial trading with the North, wanting the region’s “emigrants and enterprise.”3 He also wrote that it was necessary to repair his city’s wells, cisterns, and pumps, as well as fill the gullies and holes; clean the streets of bricks, mortar, and rubbish; and rebuild Atlanta’s market house and calaboose. This renewal had to be accomplished through loans because “all the money the city had was Confederate, which shared the fate of the Confederacy.”4 Atlanta was, in short, financially and largely physically destroyed, and it was Mayor Calhoun’s weighty responsibility to take swift action to restore the municipality’s infrastructure and economic value.

Federal occupation during the dreaded Reconstruction period was coupled with a smallpox epidemic. African Americans left their former plantations and headed toward Atlanta in droves to find employment as they also did in Charleston and Louisville. Others went farther north or tried to find their own bit of land to till. Carpetbaggers, some helped by citizens called “scalawags,” invaded Atlanta, taking advantage of distressed property owners and intertwining themselves in local politics.

By the time Benjamin Harvey Hill (1823–1882), a former Confederate senator who became a Democrat after the Civil War, declared in 1866, “There was a South of slavery and secession—that South is dead. There is a South of union and freedom—that South, thank God, is living, breathing, growing every hour”;5 Atlanta was still in the midst of rebuilding itself after the catastrophe of war. And city fathers were succeeding in their task. Indeed, that year artist and writer Thomas Addison Richards described Atlanta as “a new and thriving city.”6 The municipality also extended its city limits from the center, thereby slightly enlarging Atlanta. And in September, for the first time since the Atlanta Gas Light Company’s building was burned to the ground by Sherman, gas street lights were once again in operation.7

Hopeful signs also soon took shape for Atlanta’s visual art supporters and practitioners. These included the possibility of commissions from the Georgia State Legislature, which became a component of Atlanta’s fine art patronage in 1868 after the state capital moved from Milledgeville to Atlanta due to the latter’s railroad prowess.8 There were also other opportunities for artists. Theatrical performances of painted, narrative panoramas or dioramas were a form of entertainment (as they were in Europe and across the United States) and well attended by the Atlanta crowds in the Victorian Age. From 1860 to 1870, approximately eighty-seven panoramas were exhibited in Atlanta.9 The plot, along with a lengthy painting of more than one hundred feet literally unrolled, accompanied by music (usually played on a piano) and a narrator, who described each section as it was revealed to the audience. In 1862 at the Athenaeum on Decatur Street, Burton’s Southern Moving Panorama and Diorama featured an early Civil War battle as its main attraction.10 While these popular expressions of art raised the appreciation of it in the general citizenry of Atlanta, as well as other urban centers such as Louisville and Charleston, they were often executed by traveling artists who publicized their panoramas from place to place and did not remain in the city to build an alliance.

Other forms of theatrical and visual art appeared in the late 1860s, for the media used the term “high art,” referring to fine art, music, decorative art, and theater.11 In the following two decades, the Atlanta press more frequently utilized the term “high art” even when referring to furniture, rugs, and lady’s apparel. According to art historian Carlyn Gaye Crannell (Romeyn), high art in the Gate City for the most part had to incorporate high moral value as well as be pleasing to the eye.12 The correlation between high art and morality was not exclusive to Atlanta, however. It was an aspect of John Ruskin’s aesthetic credo and was described in the New York Times as well as in British publications from as early as 1851.13

Several Atlanta periodicals placed original oil paintings and fine engravings and etchings on a loftier tier than mere affordable chromolithographs. Art auctions were popular in Atlanta in the 1870s as well, with exhibitions a week prior to the sale so that “ladies” would have more time to convince their husbands to acquire a work. The local media approved, proclaiming that “all who can afford them should have pictures because they are pleasing to the mind, softening and humanizing to the heart and educate as well as books.”14

Liberal arts were also enhanced when, for a short period of time starting in 1870, the city was the home of Oglethorpe University (chartered in 1835) before it closed in 1872. It reopened after the turn of the century on Atlanta’s main street, Peachtree.15 An Oglethorpe alumnus, the Georgia-born poet, scholar, and essayist Sidney Lanier (1842–1881) was among those who considered Georgians to be the most broad-minded members of the southern states—much more so than South Carolinians. Therefore, Atlanta as Georgia’s hub soon became the South’s resonant symbol of progress.16 (Many New Orleanians with good reason may have protested that they were the most progressive in the South.)

Scattered art exhibitions began to appear during this time of waning Reconstruction. For example, in 1872 a large gallery display of prints and original paintings was held underneath Atlanta’s popular DeGive’s Opera House. The Atlanta Constitution saw the show as admirable and encouraged sales when it wrote, “It would be the fault of our art-loving community generally, if such handsome productions of brain and pencil are not scattered and broadcast among our homes of taste and refinement.”17

Joining the visual arts was the written word, and in the 1870s a floodtide of southern literature captivating voracious readers of books and magazines became apparent in the region—with artists enjoying employment as illustrators. Artists also portrayed the New South ideals of Henry Woodfin Grady (fig. 3). The visionary wrote one of his first editorials on the New South in 187418 and declared in 1876 “that the future of the South lay not primarily in politics but in an industrial order which should be the basis of a more enduring civilization.”19 And in the future that basis of industrial order benefited Atlanta immensely, much more so than in any of its southern rival cities.

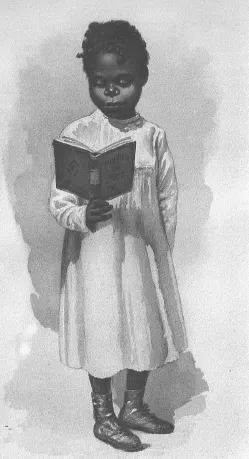

FIG. 7. James H. Moser, The Bookworm. Fetherolf collection. Grace Fetherolf, James Henry Moser: His Brush and his Pen (Sedona, Arizona: Fetherolf Publishing, 1982), 29.

In 1877 Atlanta became Georgia’s permanent capital, and Grady and his circle of artists, writers, and urban pundits soon enriched, reflected, and revitalized its civilization. Indeed, it was because of fine art connoisseurs, economic promoters, jingoistic politicians, outspoken authors, and visual artists who united to promote Atlanta’s Gilded Age and New South cultural awakening.

One of the artists in Grady’s circle was a young Atlanta native, Horace James Bradley (1862–1896). Bradley became a prime chronicler of Atlanta’s New South development thanks to his ability in drawing and watercolor, which was praised for “showing poetic feeling and a free bold handling.”20 With the assistance of Grady, the talented delineator became known as an accomplished illustrator of periodicals, including Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly. Bradley was also an influential art booster in Atlanta, establishing classes at his studio in the Young Men’s Library Association building.21

Adding to the list of urban cultural celebrities was another young painter, James Henry Moser (1854–1913), described by one magazine editor as “genial, gifted, [and] boy-hearted.”22 Moser was born in Ontario, Canada, and arrived in Atlanta in 1879, the same year the city obtained its first telephone exchange. Like Bradley, Moser was a friend of Grady’s, and he illustrated southern periodicals and books amplifying Grady’s New South message. Moser also enjoyed painting images of local Atlanta residents.

One can see in Moser’s The Bookworm (fig. 7) that he was capable of rendering Atlanta’s African Americans with artistic sensitivity. The painter was making an optimistic and individualistic comment about this little girl, portraying her as intently reading a book, the artistic symbol of knowledge. Moser stressed the practice of his craft, high ambition, and complete relish of painting the urban black community—admitting that it was his greatest joy as an artist—and while in private notations he occasionally referred to his subjects in the period’s standard jargon, he wrote that he was copiously polishing his technique in portraying them. He also compared these works to the paintings of well-known New York colleagues, such as Thomas Hovenden.23 But while Moser saw his subjects as individualized human beings, at least one of his major works would be perceived by his southern audience to be a generalized view of African Americans.

By 1881 Moser was garnering national recognition along with numerous magazine commissions he received after providing illustrations for the first edition of Uncle Remus: His Songs and Sayings; The Folk-Lore of the Old Plantation, written by his and Grady’s friend Joel Chandler Harris (1845–1908). The widely read book concerned rascally Brer Rabbit and his cronies of the Briar Patch, based on tales told to Chandler by a Georgia slave he knew as a youth—stories that were also published in the Atlanta Constitution. Sidney Lanier described Uncle Remus himself as a “famous colored philosopher of Atlanta who is a fiction so founded upon fact and so like it as to have passed into true citi...