![]()

1

THE SLAVE’S DREAM

Besides the ungathered rice he lay,

His sickle in his hand;

His breast was bare, his matted hair

Was buried in the sand.

Again, in the mist and shadow of sleep,

He saw his native Land.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “The Slave’s Dream”

The landscape served as the canvas upon which enslaved men and women forged a life and identity during the antebellum and postbellum period. This chapter establishes in lowcountry Georgia a sense of place, defined as a “feeling and understanding of a particular locale inscribed over time” by those who lived and traveled there.1 The ambivalence of the landscape as a place of terror and community is narrated through the individual and collective voices of African Americans who reenvisioned their objective reality by challenging the isolation of their physical geography; they engaged in what Toni Morrison fashioned as remembering and (dis)remembering elements of their African culture through revisions of the past and through political activity.2 In this chapter, political activity is understood as an organized collective action that affects power relations. Sterling Stuckey, Lawrence Levine, and Eugene Genovese have each looked beyond subversive acts for evidence of the deeper cultural and social resistance found in folkways, religious practices, and family life.3

Lowcountry Georgia emerged as the principal area for antebellum rice production. As late as 1860, twelve of the seventeen largest slave owners in the United States were rice planters.4 Moreover, rice plantations were larger than other staple crop plantations in the South and in several respects resembled Caribbean estates. By 1830 rice had surpassed cotton as king in Georgia’s five coastal counties: Chatham, Liberty, McIntosh, Glynn, and Camden. This region is divided into six natural ecosystems: barrier islands, coastal marine, estuaries and sounds, mainland upland, rivers, and swamps. The growth of rice in Georgia depended on the tide-flow method, the unusual requirements of the soil, and the knowledge and skill of enslaved Africans and African Americans. The tide-flow method required the flooding and draining of rice fields on the basis of tidal fluctuations. Because rice growth requires fresh water, rice lands were located above the saltwater lines on freshwater rivers. Furthermore, rice lands were positioned where the freshwater level could be raised by each high tide.5

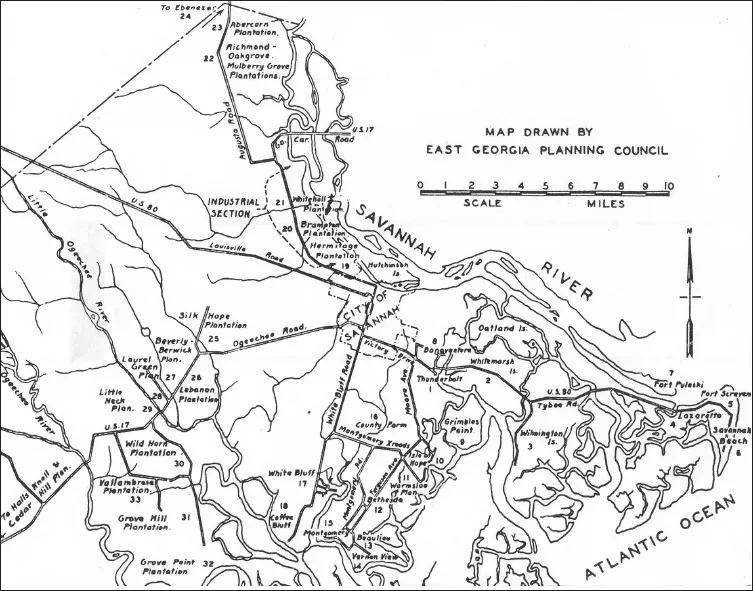

The soil required for growing good rice crops consisted of clay and swamp muck. As a part of the subsoil, clay retained water well when flooded and thus prevented the fields from losing large amounts of water through leakage. The region’s five large rivers, Savannah, Ogeechee, Altamaha, Satilla, and St. Mary’s, were vital to the growth of rice and served as the focal point for settlement.6 In coastal Georgia, transformation of the landscape emanated from the knowledge systems of Africans who were transplanted from rice-growing regions in West Africa. By 1860 three principal watershed rice districts had emerged: the Savannah-Ogeechee district, located between the Savannah and Ogeechee rivers; the Midway district, located between the Savannah and Altamaha rivers; and the Altamaha district, which stretched from the Atlantic between the Altamaha and St. Mary’s rivers. By definition, a watershed is the land area which contributes surface water to a river or other body of water. The boundaries of a watershed are formed by a high point and all water flows down to the lowest point or watershed outlet. Settlement in watershed areas is characterized by a complex system involving social, ecological, and physical factors. The water served as a powerful unifying force in watershed districts.7

Along the Savannah and Ogeechee rivers, over 12,000 enslaved Africans labored on lowcountry plantations.8 These plantations included Vallambrosia, Grove Point, Grove Hill, and Wild Horn, which were established by descendants of wealthy South Carolina planters. Daniel Blake of South Carolina purchased 1,321 acres of land, which comprised Vallambrosia plantation, from Stephen Elliott in 1827.9 A few years later, Arthur Heyward, who married Blake’s daughter, purchased the land and expanded it to 2,692 acres.10 During this same period, Stephen Elliott consolidated Grove Hill plantation from the initial 840 acres purchased in 1797 to 1,340 acres. Elliott’s son, Reverend Stephen Elliott Jr., sold the plantation to William and Stephen Habersham in 1849.11

Stephen Habersham began acquiring land in the Ogeechee area in 1848, when he purchased 900 acres from Francis H. MacLeod’s estate.12 MacLeod inherited Wild Horn plantation in the early 1800s from his grandfather Francis Harris, a speaker of the Colonial Assembly and a partner in the mercantile firm Habersham and Harris. Harris enlarged his initial 500-acre land grant to 3,400 acres.13 Similarly Grove Point plantation initially consisted of 500 acres granted to South Carolina planter-merchant James Powell, who received a total of fifteen land grants in Georgia, totaling 6,645 acres.14 In 1846 John R. Cheves purchased Grove Point plantation, which consisted of 1,500 acres.15

Plantation districts Savannah-Chatham County

The Midway watershed community included Bryan, Liberty, and McIntosh counties; the latter was at the geographic center of Georgia’s rice coast in 1860. Two of the earliest cotton and rice plantations were constructed on St. Catherine’s Island in Liberty County and on Sapelo Island in McIntosh County. Jacob Waldburg developed extensive holdings on St. Catherine’s Island, which at its peak, in 1853, included 255 enslaved Africans and African Americans. Waldburg also owned properties in Savannah.16 Similarly Thomas Spalding owned extensive rice, cotton, wheat, and sugar cane plantations on Sapelo Island, where 300 enslaved Africans and African Americans labored in 1853.17 According to the 1860 census, 41,084 Georgia slaveholders had an average of 11.2 slaves each, with owners in Liberty and McIntosh counties holding double the state average.18 By 1850 the largest planters in the Midway district, holding over 200 slaves, included Pierce Butler, with 505 bondmen and bondwomen on Butler’s Island; and Randolph Spalding, with 252 enslaved persons.19

The Altamaha River estuary served as a natural divider for the islands south and north of the Altamaha, where the third watershed district developed. As the Altamaha approached the sea, it partitioned into several channels that joined, separated, and rejoined each other in the marshland of the river’s delta.20 The marshlands and tidal rivers surrounding St. Catherine’s, Ossabaw, Sapelo, St. Simons, and Jekyll islands provide the intellectual framework for examining the interrelationship of land, space, and the creation of narratives of freedom.

The rice coast communities emerged as a result of three inwardly related and complementary historical developments: extensive headright privileges granted in the Georgia state constitution, the forced migration of thousands of Africans, and the concomitant transformation of the natural landscape. To encourage settlement of Georgia’s new counties, the state constitution provided headrights for prospective settlers in 1777. Each household head would receive two hundred acres, and the state provided fifty acres for each additional free person or slave. A 1783 amendment allowed applicants to acquire up to one thousand acres in the coastal counties.21 By 1790 the population of the counties, with the exception of Chatham, remained under five hundred, with enslaved Africans making up the majority of the population.22

On Glynn County’s St. Simons Island, the landscape epitomized the individual and collective ordeal of slavery. Separated from the sea by Little St. Simons Island, which confronts the Atlantic Ocean and Altamaha Sound with an expanse of hammock land, marshes, dunes, and sand beaches, St. Simons contained Hampton, Hopeton, Retreat, and Cannon’s Point plantations. These rice coast communities developed under the influence of Thomas Butler King, Hugh F. Grant, John H. Couper, Thomas Spalding, and Pierce Butler. Within the Altamaha watershed district, 1,700 acres of land formed the nucleus of Butler’s St. Simons properties, an expanse of land stretching across the northern end of Little and Greater St. Simons islands.23 Butler’s holdings consisted of four cotton plantations on St. Simons Island and a rice plantation on Butler’s Island. Six hundred acres on the Altamaha delta that consisted of mostly marshland to the north and west of Hampton became known as Five Pound Tree, which symbolized the fractured lives and the submerged voices of enslaved African Americans in that it served as an isolated home for the unruly. Coterminous with Five Pound Tree was an expanse of two thousand acres of marshland that became what was called the Experiment plantation.24

Butler’s Island serves as a spatial paradigm in which to view the conception of space within the coastal environment. Lying south and west of Darien and located ten miles upstream from Hampton, Butler’s Island contained 1,500 acres of land, with more trees than marshland. Enslaved Africans banked and then cleared the land with hand tools for the cultivation of rice.25 The high bank around the perimeter was nine miles in length. The removal of soil from the island side of the bank resulted in a large ditch that became a combination of aqueduct and canal. They placed floodgates and trunks (wood culverts) strategically in the high bank to facilitate the introduction of fresh water with the rise and fall of the river. Additionally they prepared a vast grid of banks, canals, and ditches, and drains and quarter drains from the heavy growth of the river swamp.26

The transition from long-staple cotton to rice production occurred following the perfection of the cotton gin in 1793. The exclusion of salt water from the incoming flood tides made the growth of rice possible along the Altamaha. From the beginning, enslaved African Americans directed the interior landscape by constructing a canal three hundred yards long, four feet wide, and eight inches deep that improved communications and access to Hampton.27 Both the task labor system and the gang labor system were employed on Butler’s Island and St. Simons Island. The growth of long-staple cotton required the use of the gang labor system. Moreover, seven horses and seven workers were required to operate the cotton gin, which freed the cotton of most of its seed. An ancillary step called moting required women to pick broken seeds and debris out of the cotton by hand and to winnow the cotton over a fan for further cleaning. On St. Simons Island, the cotton gin produced four hundred to five hundred pounds of clean fiber daily. The cotton was forced into three-hundred-pound bags by the compressing screw, and if it was sent on to Savannah or Charleston, it would be further compressed by more efficient equipment.28

On Butler’s Island, four settlements determined the spatialized power relations within the natural landscape. The four settlements consisted of the overseer’s house, located on the highest, most accessible land; the garden; the plantation complex, which consisted of the machine shops, the rice mill, and the sugar mill; and the slave quarters. Near the Champney River, located on the back side of the Altamaha, were the garden, the plantation complex, and the larger slave quarters.29 These settlements were protected from flooding within the island by their own lesser banks. As in other watershed communities, the river landing and its wharf were an integral part of this landscape. In the Altamaha watershed community of Camden County, Robert Stafford established extensive landholdings on Cumberland Island, consisting of over 4,200 acres for the cultivation of rice and sea island cotton worked by 348 enslaved Africans in 1850. By 1860 the Altamaha watershed community included 2,785 enslaved Africans and African Americans who worked 8,000 acres of land.30

Within the established watershed communities, resistance to enslavement became an integral part of the landscape. Materials as divergent as slave narratives, the post-Civil War petitions of former slaves, plantation records, and journals yield a composite picture of the complexities of the slave system that underscores the diversity of responses to the system. Collectively these materials demonstrate that narratives of resistance and freedom were a form of discourse within certain limits and with a conceptual language that established human agency. These narratives represented an attempt to construct an identity, a set of relationships, and boundaries for negation, resistance, and reinterpretation of their lived experience.31 Resistance and freedom persisted in the consciousness of enslaved Africans and African Americans in lowcountry Georgia.

TABLE 1. Rice Production in Lowcountry Georgia, 1860

COUNTY | POUNDS PRODUCED |

Chatham | 25,934,160 |

Camden | 10,330,068 |

McIntosh | 6,421,100 |

Glynn | 4,842,755 |

Liberty | 2,548,382 |

SOURCE: U.S. Census Manuscript Agricultural Returns, 1860.

Within the first generation of Africans in the lowcountry, a substantial number were West Coast Africans from the Senegambian region and Sierra Leone. The nearly two dozen ethnic groups with representation along the west coast from Senegal to Sierra Leone, and from Angola at various times, provided the ideological superstructure upon which to express r...