![]()

Chapter One: Where Chicagoans Found Nature

An Expedition with Leonard Dubkin, Urban Ranger

The common weeds, in spite of man’s militant opposition, survive and flourish everywhere.… As an example of the hardy, well-adjusted weed, take the dandelion. Through the years man has fought this weed with every resource known to science, and he has succeeded in keeping it out of cultivated areas only with much effort and a great deal of expense. The dandelion grows everywhere, in city lawns and parks and yards, in country fields and meadows and swamps, on mountainsides and on the edge of deserts. It is probably as perfect, as well-integrated, as sensitive and as “intelligent” a plant as can be found anywhere in the world.… A single dandelion flower is to me, not for what it is in itself, or in competition with other, more lavish blooms, but for what it represents, for the vitality, the toughness, and the logical balance that went into its production, the most beautiful of all flowers.

—LEONARD DUBKIN, Enchanted Streets: The Unlikely Adventures of an Urban Nature Lover, 1947

During their summer vacations, tens of thousands of turn-of-the-century Chicagoans left their “artificial” city and traveled into what William Cronon calls the recreational hinterland: scenic areas of Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan; and national parks, such as Yellowstone. In such faraway places, many felt that they could escape the work, exhaustion, illness, and artifice they associated with Chicago and come into contact with the restorative power of nature.1

Marginalized Chicagoans—Germans, Irish, Poles, African Americans, groups of working-class neighborhood youth, and trade unionists—also made this leisure-time exodus out of the city and back to nature, especially as transportation costs fell during the early twentieth century. As we will see in the following chapters, Chicagoans traveled to wilderness parks, such as the Indiana Dunes, but also to ethnic and labor resorts, such as Camp Sokol, Illinois Turner Camp, Idlewild, Camp Pompeii, Camp Chi, Harcerstwo Camp, and the Chicago Federation of Labor’s Camp Valmar. For others, nature was even further afield, back in distant homelands: the forests of southwest Germany, a small village on the Aegean, the rich farmland of occupied Poland, the grasslands and mountains of Jalisco, a rice-growing village in Guangdong, the peaks of the Carpathians, or the dunes of Lithuania’s Baltic Coast.

These destinations, though, were for the lucky few. Working-class Chicagoans typically stayed home, back in the hot, polluted city. They simply did not have the time or the money to spend a long weekend in the lakes and forests of rural Michigan or Wisconsin much less take a pleasure trip back home to a distant German, Irish, Swedish, or Mexican homeland. But this lack of means hardly implies that these Chicagoans were blind to the attractions of nature—far from it. Even though they could not afford to vacation outside the physical parameters of the city, they could and did seek out green spaces closer to home, on the urban fringe or within the city itself.2

In this chapter, we will survey some of these urban and peri-urban landscapes where Chicagoans found nature. We will visit six major nineteenth-century pastoral parks, dozens of smaller neighborhood athletic parks, the Lake Michigan shore, and a crescent of forest preserves that enclosed the city to the north, west, and south. We will explore commercial groves, beer gardens, and amusement parks located throughout the city as well as unexpected green spaces: vacant lots, railroad rights of way, alleys, industrial yards, wharfs, canals, the Chicago River, and even sidewalk cracks.

We need a reliable guide or “urban ranger” for this expedition, and there is none better than Leonard Dubkin. In 1907, Dubkin (who was two years old at the time) immigrated to Chicago with his Ukrainian Jewish parents. Like many other impoverished newcomers, the family moved to the slums of the Near West Side. This neighborhood was the home of Hull House, the famous “settlement” administered by Jane Addams and other native-born middle-class women who made it their mission to aid the urban poor. Although Dubkin lived in a small apartment in a densely packed urban environment completely devoid of trees (he saw his first tree when he was nine or ten years old), he developed an early interest in the natural world and hoped to become a naturalist when he grew up. As a teenager in an impoverished family, he spent most of his time going to school and working (delivering newspapers and cleaning saloons), but when he had a spare moment, he avidly read Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, Ernest Thompson Seton, and other famous naturalists and went on collecting trips around the city. He stuffed birds, mounted butterflies, collected rocks and fossils, and brought living snakes, turtles, snails, and crayfish back to his parent’s crowded tenement. Using a public typewriter at Hull House, Dubkin wrote stories about his adventures with urban nature, which the Chicago Daily News published regularly on the Sunday children’s page. Impressed, Jane Addams gave the boy a new typewriter as a gift. Although Dubkin never became a professional naturalist as he had hoped (he did not have the means to go to college), he did go on to write six books on nature in the city, publish numerous articles on nature for the Chicago Daily News and the Chicago Tribune, and correspond with famous naturalists, including the nature writer and ecologist Rachel Carson.3

Unlike the largely affluent and Anglo American members of the Prairie Club who traveled out of the city in search of original, uncontaminated Illinois, Wisconsin, or Indiana wilderness, Dubkin insisted that nature could be found within the very city that so many elite Chicagoans spurned. Whether we go to nature for knowledge, beauty, or recreation, there was no need to leave the city, he told his readers. All we have to do is open our eyes to the nature around us.

Pastoral English Parks in Chicago

If Dubkin were to give us a tour of the places where Chicago’s disadvantaged sought nature, he would probably begin by taking us to the city’s great nineteenth-century pastoral parks. During the second half of the nineteenth century, Anglo American politicians, intellectuals, and physicians in cities across the nation called for the development of large urban parks, such as Manhattan’s Central Park, which was opened to the public in 1857. Advocates claimed that these parks would increase surrounding property values and bring culture to unrefined frontier cities. Public parks would also further American republicanism because they gave all citizens access to restorative private park landscapes that were monopolized by aristocrats back in Europe. But foremost among the justifications for spending public money on the creation of these landscapes was health. These green oases would serve as a natural resort where one could retreat and recover from the ill effects of artificial urban life.4

This priority on health can clearly be seen in the writings of John Rauch, a medical doctor who was the most influential early advocate of Chicago parks. He explained in 1869 that Chicago was an “unnatural and artificial” environment where residents devote themselves single-mindedly to work, the acquisition of wealth, and the accomplishment of something “bold and novel,” all of which creates an “atmosphere of excitement, more so, perhaps, than any other community in the world.” One downside of such an overly stimulating and artificial environment, he wrote, was “expenditure of physical and mental force,” which led to premature exhaustion, inability to work, and a host of diseases, such as apoplexy, dropsy of the brain, consumption, dyspepsia, convulsions, epilepsy, and palsy. For Rauch, the answer was not a wholesale evacuation from the unhealthy urban environment, but rather the development of large city parks where Chicago residents could temporarily escape unhealthy urban conditions.5

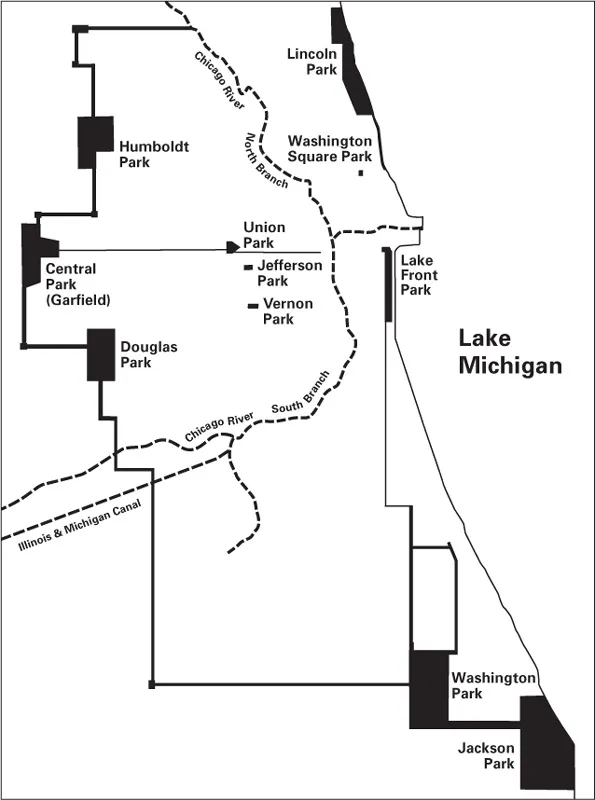

Chicago ultimately followed Rauch’s advice. After opening Lincoln Park in 1865, the city began work on Humboldt, Garfield, and Douglas Parks on the West Side and Washington and Jackson Parks on the South Side (see Map 1.1). Given that park builders understood these landscapes as natural retreats from an artificial city, we might think that these nineteenth-century parks, with their rolling greensward, banks of irregular trees and shrubs, and quiet ponds, preserved the original native Illinois landscape that existed before Chicago became a city. But our guide would undoubtedly quickly disabuse us of this notion. Although Dubkin had no formal training as a naturalist, he had more than enough knowledge of native plants, animals, and topography to quickly recognize that these parks hardly preserved last vestiges of indigenous prairie wilderness.

Victorian park builders such as Frederick Law Olmsted, the dean of nineteenth-century American landscape architecture and the most influential midcentury advocate for parks, certainly believed that untamed sublime scenery had its place. Olmsted called for protecting the Yosemite Valley and Niagara Falls, and he incorporated the seemingly untamed Ramble into his design of Manhattan’s Central Park. But at Yosemite, he was much more interested in the pastoral valley floor than the surrounding “cliffs of awful height.” At Niagara he focused on the parklike virtues of Goat Island rather than directing attention to the overly stimulating cataracts. And in reference to urban parks, he advised in 1870 that they should not contain “very rugged ground” or “abrupt eminences.” What is needed is “the beauty of the fields, the meadow, the prairie, of green pastures, and the still waters. What we want to gain is tranquility and rest to the mind. Mountains suggest effort.” In an overwrought, overworked, and “nervous” nation where many still associated the wilderness with danger, terror, and toil, Olmsted—like other landscape architects of his generation—always subordinated unruly sublime and picturesque scenery to the far more soothing pastoral.6

MAP 1.1 Chicago parks and parkways in 1888. Based on “Index Map of Chicago: Running South to Seventy First Street” (Chicago: Rufus Blanchard, 1888).

Courtesy of the Map Collection, University of Chicago Library.

Landscape architects working in Chicago (including Olmsted) sometimes saw the sublime scenery of Lake Michigan as a potentially important element in urban park design. But, as historian Daniel Bluestone demonstrates, they found absolutely no value in the native prairies, marshes, forests, and dunes that sometimes still existed in reduced and simplified form in and around Chicago. Victorian park builders found the indigenous landscape exhausting and depressing, not refreshing or rejuvenating. Olmsted, for instance, described the Illinois prairie as “one of the most tiresome landscapes that I have ever met with,” and he noted that “Chicago is situated in a region most unfavorable to parks and should she ever have any that are deserving the name, it will be because of persistent wisdom of administration and a scientific skill as well as art … such as has been no where applied to similar purpose.” One of Olmsted’s contemporaries, the landscape architect H. W. S. Cleveland, asked, “by what means is it possible to give to areas so utterly devoid of character an expression of natural beauty, and secure enough variety to relieve their monotony?” He answered that in Chicago, “everything must be created. Nature has not even offered a suggestion for art to develop.”7

Instead of trying to preserve or reproduce the original “wild” landscape, Chicago landscape architects looked back East, in particular to Europe, especially England. In the early eighteenth century, English gentry began to turn away from rigid geometric gardens, such as those found at the Palace of Versailles, just outside Paris. Instead of linear walks, manicured trees and topiary, symmetrical beds, and elaborate fountains, English landlords embraced a far more informal garden composed of rolling greensward, informal groupings of trees, serpentine paths, and still ponds.8

Cultural critic Raymond Williams links the emergence of the informal English park to changes in agricultural production occurring throughout rural England during the eighteenth century. The quest for greater agricultural efficiency drove landlords to enclose or fence in common lands used for gardening and grazing and to evict tens of thousands of peasants, many of whom left for cities and colonies. The enclosure of common lands (as well as profits from colonial trade) meant increased profits for the landlord gentry, who symbolically expressed their newly gained wealth in the form of fashionable country estates surrounded by extensive, well-maintained landscape gardens. As the rectilinear, efficient, and productive field rigidly surrounded by stone fence or hedge became an increasingly common site throughout England, the English landscape architects of the eighteenth century abandoned level and line in favor of sweeping curves, serpentine lakes, and expanses of open meadow framed by irregular banks of trees and shrubbery. As the gentry took part in the destruction of the commons and as they benefited from market-oriented agriculture and the displacement of English cottagers, they simultaneously re-created a lost classical or medieval pastoral world for their own private use.9

During the nineteenth century, the informal English park captured the imagination of landscape architects working not only in England, but also in France, Germany, Australia, South Africa, India, and the United States. Olmsted, for one, noted that the medieval English deer park (whether original or reproduced by landscape architects) possessed an unrivalled therapeutic effect. It was doubtful, he wrote, whether there was any other natural scenery that was “equally soothing and refreshing, equally adapted to stimulate simple, natural, and wholesome tastes and fancies, and thus to draw the mind from absorption in the interests of an intensely artificial habit of life.”10

In Chicago, landscape architects such as Olmsted, Cleveland, Swain Nelson, and William Le Baron Jenney transformed flat treeless prairies, wetlands, sand dunes, and other “wastes” into therapeutic parks in the English style. In Lincoln Park, Lake Michigan dunes dominated the site, and commissioners noted that “it is easy to perceive that a range of windswept sand hills is an unpromising place for a park, but hard to conceive of the immensity of the task of subduing it to verdure and beauty.” The commissioners’ laborers uprooted existing scrub oak, moved sand with plow and scraper, spread ten thousand loads of street sweepings on the ground, and created ponds, mounds, and ridges. They planted thousands of native and exotic trees in irregular patterns, planted grass, and applied millions of gallons of irrigated water to the sandy soil. Using pilings, oak plank, and huge blocks made of Portland cement, they also built tremendous breakwaters against Lake Michigan waves, the park’s “unresting enemy.” As in New York’s Central Park, the commissioners even released nonnative English sparrows. As an 1896 guidebook to the park noted, “The great beauty of Lincoln Park is … in no wise due to original gifts of nature … but is, on the contrary, essentially artificial, the ‘work of men’s hands,’ and thus is a triumph of man’s skill over adverse natural conditions.”11

On the city’s West Side, landscape architects created English parks (Humboldt, Douglas, Garfield) on sites seen as even more unfavorable. One writer described the unimproved parklands as “an unbounded expanse of bleak plain, destitute of vegetation, except low … [vegetation] and a distant line of spindly young trees, hardly more sylvan in appearance than telegraph poles. In the foreground are stagnant pools of water and an unfenced, ungraded prairie trail. The scene is as barren, lone and desolate as could well be conceived.… There was upon the whole tract not a single tree of natural growth worthy of preservation.” To build parks on the “bleak” indigenous landscape, the city chose William Le Baron Jenney, an engineer who, in the 1850s, had studied in Paris, where he had witnessed urban planner Baron Von Hausmann’s modernization efforts, including the construction of English-style parks (such as the Bois de Boulogne in Paris) favored by Napoleon III. On Chicago’s West Side, Jenny followed the Parisian model. By digging o...