![]()

Part I : The Ship

![]()

1 : The Gay Head Harpooner

Native American whalemen’s motivations and working life underwent a notable shift in the 1830s as the American whaling industry rapidly expanded. The number of whaling voyages doubled from the 1810s to 1820s, doubled again in the 1830s, and peaked at midcentury, with over 2,000 departures per decade in the 1840s and 1850s.1 The concomitant rise in labor demand placed new value on native whalemen’s skills and commitment. Because whaling was a relentlessly dismal occupation that drove most white men away, a niche opened for native men to fill the need for capable officers. How race informed native New England men’s participation in the whaling industry evolved, too, as employers in search of a large, flexible workforce drew on racial presuppositions selectively.2

At the start of the nineteenth century, whaling crews consisted almost entirely of white, African American, and Native American men local to coastal New England, and ship owners overtly used race in hiring by treating men of color as an undifferentiated racial underclass. Whaling records from the first few decades of the nineteenth century usually included native men among the “Black Hands,” “blacks,” or “coloureds” at the end of crew lists as though race was equivalent to rank and a low rank at that.3 Notions of Indians as childlike dependents added another racial dimension, since men living on reservations fell under the authority of state-appointed, white guardians. These guardians often helped whaling agents acquire labor. One notorious instance occurred in 1799, when Barnstable County authorities kidnapped two Pocknett brothers with the approval of a Mashpee guardian under the claim, or pretense, of debt. Transmitted to a Nantucket whaleship, where they refused to sign the shipping articles, the Pocknetts had no recourse but to go the length of the two-year voyage.4 Such machinations led to native complaints that their “men are sent [on] Long voiages to sea by those who practice in a more soft manner that of Kidnaping who when they Return with ever so great success they are still In debt.”5

Coercive hiring practices were on their way out in the 1820s, but middlemen found new ways to glean a profit and often targeted men of color. Gideon Hawley, missionary at Mashpee and frequently also guardian, called these middlemen “Indian speculators.” They bought and traded shares in a whaleman’s potential earnings, claiming the prerogative to place him on a vessel of their choosing.6 In an 1820 agreement between seventeen-year-old Aaron Keeter of Mashpee and Percival Freeman, Keeter’s mother signed the contract because he was under age, and then, because he was a Mashpee Indian, the tribe’s guardians signed also. Percival Freeman received half of Keeter’s anticipated profits on a three-year voyage by paying Keeter $100 and his outstanding debts. Freeman shipped Keeter on the Nantucket whaler Dauphin.7 The need for immediate income may have driven the impoverished to accept unfavorable terms when selling profits in advance but not without negotiation. A traveler on Martha’s Vineyard reported how Indian whalemen held out for cash advances or gifts of clothing and food before signing a contract.8 By receiving cash or goods up front, whalemen let middlemen assume the monetary risk, but they still shouldered the greatest risk in the high rates of death, disablement, and abandonment in a foreign port, fates endemic to the whaling occupation.

By the 1830s, these middlemen also faded from the scene. One class of middlemen remained, whaling outfitters, who advanced clothing and supplies to nearly all whalemen, no matter their race, but did not trade in voyage shares. And there were no more complaints about guardians helping whaling agents extort labor. In 1828, the Massachusetts legislature passed a law endorsing the Christiantown and Chappaquiddick guardian’s authority to “bind out” for the length of a voyage any who were “habitual drunkards, vagabonds, and idlers.”9 However, guardians seem not to have exercised this power, and there is no evidence of native men being shipped against their will after this law passed. Guardians continued to act as intermediaries, however. They collected and disbursed whaling earnings, which native whalemen must have considered both a bureaucratic nuisance and humbling reminder of their status as government wards.10 But guardians could also advocate for them in disputes with employers, as Leavitt Thaxter did in a lawsuit against Lawrence Grinnell for the earnings of Samuel P. Goodridge. A Wampanoag of Chappaquiddick, Goodridge had died in 1836 in the Galapagos Islands while serving aboard the Euphrates of New Bedford. Thaxter had purchased on outfit for Goodridge from a local vendor, but so did Grinnell as agent for the Euphrates. After Goodridge’s death, Grinnell retained Goodridge’s earnings to pay for the outfit. Thaxter lost his suit on behalf of Goodridge’s heirs, and the judge reprimanded him for expecting the ship owners to discern that Goodridge was a Chappaquiddick Indian with a legal guardian.11 The native community at Chappaquiddick defended Thaxter. Hearing a rumor that “our white neighbours” were trying to eliminate the guardianship system, they appealed to the legislature to keep it in place because “most of our Young men are employed in the Whale fishing and often need assistance in settling their voyages.”12 Thaxter’s defeat in court and the mounting critique of the 1828 law as inhumane reflected the rise of a free-labor ideology in antebellum America that celebrated voluntary participation in the labor marketplace as a man’s right.13

In the 1830s, native whalemen began to benefit from opportunities that white men had always had. In 1816, seventeen-year-old Elemouth Howwoswee of Gay Head would not have presumed as he boarded the Martha that he might advance up the ranks as could his shipmate Walter Hillman, of the same age and also from Martha’s Vineyard but white. The two went out again on the Martha the following year, Hillman as third mate. By 1822, Hillman had risen to first mate and the year after that to master of the Maria Theresa. Howwoswee was on the Maria Theresa, too, and served under Hillman’s command off and on over the next few years, by chance or because of some personal bond between them. After sixteen whaling voyages, Howwoswee died at sea at age forty-two still a boatsteerer, whereas Hillman had captained seven voyages.14 A generation later, native men’s prospects had turned around. Joel Jared started whaling at age sixteen on the Adeline in 1843, where he worked alongside six other Gay Head men, including first mate George Belain and third mate Jonathan Cuff. Immediately upon the Adeline’s return to port, Jared shipped as boatsteerer on the Amethyst and subsequently as third mate on the Samuel & Thomas in 1850. He ended his career as second mate on the Anaconda in 1856–1860. He might have gone further had he not died at Gay Head the year after the Anaconda’s return.15 Many had similar career trajectories, including the Belains, Goodridges, and Goulds from Chappaquiddick; George and James W. DeGrass from Christiantown; the Jeffers, Johnsons, and Cooks from Gay Head; Jesse Webquish’s sons Nathan, Jesse Jr., Levi, and William from Chappaquiddick and Mashpee; Asa and Rodney Wainer from Westport, Massachusetts; the Ammons brothers, Joseph and Gideon, from the Narragansett reservation in Charlestown, Rhode Island; and Milton, Ferdinand, and William Garrison Lee, belonging to a Shinnecock family on eastern Long Island.16

As the industry declined in the latter half of the nineteenth century, agents and captains continued to place Native American men in positions of authority. For example, Francis F. Peters and Alonzo Belain of Gay Head, both seventeen years old, embarked on their first voyage together on the Sunbeam of New Bedford in 1868.17 When the Sunbeam returned three years later, they advanced to boatsteerer on their next voyage, Belain on the Kathleen, Peters on the Atlantic.18 They then shipped on their third and final voyages, Belain as third mate on the Triton and Peters once again on the Atlantic but now as fourth mate.19 Belain died from consumption while at sea in 1877, at just twenty-six years of age.20 Peters was promoted to third mate during his voyage but died a year later when the Atlantic lost two boats crews at sea while whaling.21 Each voyage elevated the men another notch up the ranks, and if they had not died young, they might have made it as far as second or first mate.

Native Americans thrived in the whaling industry but only up to a point. Few became captains or investors. Most of those who did had connections to the mixed Wampanoag and African American families of Cuffes and Wainers in Westport, Massachusetts, and Bostons of Nantucket. In the 1790s, Paul Cuffe and his brother-in-law Michael Wainer bought their first whaler, the Sunfish. Wainer’s son Paul served as captain on the Protection in 1821 as Cuffe’s son William did in 1837 on the Rising States. This last excursion ended quickly and poorly, with Cuffe dead and the vessel condemned.22 On Nantucket, Absalom Boston commanded the Nantucket ship Industry in 1822, but it also failed to turn a profit.23

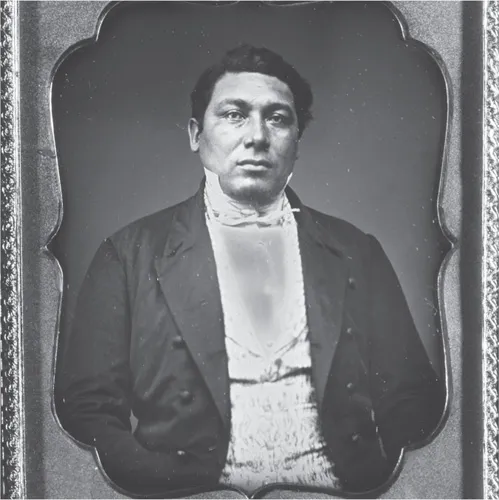

Otherwise, in the entire nineteenth century, only three native men—Amos Haskins, Ferdinand Lee, and Joseph G. Belain—reached whaling master. Amos Jeffers of Gay Head almost made a fourth. Returning to New Bedford in 1847 as first mate on the Mary, Jeffers agreed to take the vessel out again as captain, but while waiting for the vessel’s outfitting, he drowned in a fishing accident off of Gay Head.24 Amos Haskins encountered misfortune, too (figure 3). As first mate, he took over for a sick captain left at Fayal and brought the bark Elizabeth safely home to Mattapoisett in 1850 with 1,060 barrels of sperm whale oil aboard, an impressive cargo for a seventeen-month voyage. The following year, Haskins took command of the Massasoit but made a disastrous showing of only 325 barrels. One more venture on the Massasoit, cut short by a fever among his crew that killed four and downed seven others, returned a mere sixty barrels.25 Haskins continued whaling, as first mate, and died on the March, lost at sea in 1861.26 First mate Ferdinand Lee similarly gained the confidence of shipping agents when the Eliza Adams arrived at New Bedford in 1871 with a “splendid catch.”27 Given the command of the Callao for four years, he generated a mediocre cargo that proved a financial loss for its owners.28 Lee did not give up on whaling either. He died a second mate, along with first mate Moses Walker and several other Shinnecock men, when the Amethyst was crushed by Arctic ice in 1885.29

According to one study, perhaps as many as 40 percent of whaling masters from New Bedford made only one voyage, so Haskins’s and Lee’s brief tenures were not unusual.30 But because so many native whalemen became officers while so few realized that final step to become captains, clearly the color line had not disappeared. It merely shifted to allow Indians to serve as officers. Hired as first mate on the Palmetto in 1875 at age twenty-five, Joseph G. Belain held that rank for decades except when he replaced the captain of the San Francisco-based whaler Eliza for the 1890 Arctic season.31 Other native first mates took charge of vessels upon the illness or death of captains without official recognition as captain.32

Figure 3. Amos Haskins, captain of the bark Massasoit of Mattapoisett on its 1851–1852 and 1852–1853 voyages. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

African American whalemen were equally rare in the highest echelons of the industry. Among those few who became whaling masters were two men connected by marriage to native families. Pardon Cook, Paul Cuffe’s son-in-law, headed five whaling voyages in the 1840s, all out of Westport, the Cuffe family’s home port.33 William A. Martin married Sarah Brown of the Chappaquiddick community, where the couple resided. Martin later became captain of the Golden City in 1878, the Emma Jane in 1883, and the Eunice H. Adams in 1887.34

Although native seafarers mostly worked as whalemen, some opted to stay closer to home on small trading vessels. Solomon Attaquin of Mashpee went whaling in his youth but in 1837 transported wood to Nantucket as captain of the newly built sloop Native of Marshpee.35 Solomon Webquish, whose brothers rose to prominence in the whale fishery, preferred coastal trading also, with Plymouth as his home port.36 And Aaron Cuffee—the only native whaleman I know of with scrimshaw attributed to him in a museum collection (an “ivory swift,” or yarn winder, in the Sag Harbor Whaling Museum)—was captain of a New London–Sag Harbor steamship later in life.37

Native ownership of whaling vessels was rare as well, if not by choice then because of its great cost. Not only did owners have to invest several thousand dollars in the purchase of a vessel; they had the expense of outfitting it for a lengthy voyage. Missionary Dwight Baldwin obtained specifics on cost and profitability on his way to Hawai‘i on the whaleship New England in 1831. Built originally for the China trade, the New England cost its whaling investors $17,500, with an additional $12,500 put toward outfitting it, for a total investment of $30,000. Larger than most whalers at 376 tons, the New England carried enough casks for 3,800 barrels of oil. A sufficiency of 3,200 barrels, reaping $60,000, would make the trip worthwhi...