![]()

Part I: U.S. History to 1877

![]()

Chapter 1: Borders and Borderlands

JULIANA BARR

This essay collection rests on the straightforward premise that American Indians are crucial to the teaching of U.S. history. Yet some might ask, “Why Indians?” The clearest response is that North America was not a “new world” in 1492 but a very old one with a history far lengthier than what has come since. More specifically, at the time of European invasion, there was no part of North America that was not claimed and ruled by sovereign Indian regimes. The Europeans whose descendants would create the United States did not come to an unsettled wilderness; they grafted their colonies and settlements onto long-existent Indian homelands that constituted the entire continent. We cannot understand European and Anglo-American colonial worlds unless we understand the Native worlds from which they took their shape.

It seems an odd realization that in teaching American history we discuss Indian sovereignty and bordered domains primarily in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when they were most under assault by U.S. policies that sought to dispossess Indian nations of land and disenfranchise them of their power. Thus we tend to talk about Indian sovereignty in negative terms—as something they were always in the process of losing over the course of U.S. history. Yet we need to address sovereignty in positive terms because we cannot begin to understand how Euro-American colonialism wore away at it unless we first know how Indians exercised power over the land and vis-à-vis their Native and European neighbors.

Thus we must begin by acknowledging the fundamental essence of Indian sovereignty—“the power a nation exerts within unambiguous borders.”1 More specifically, we must recognize “how Indians understood territory and boundaries, how they extended power over geographic space, and how their practices of claiming, marking, and understanding territory differed not only from Europeans’ but also from each other’s.” In my own research, if one compares the border marking of hunter-gatherers, sedentary agriculturalists, and mounted hunters and raiders in the region that would become Texas and the southern plains, one finds that residency, economy, trade, politics, raiding, horticulture, hunting, ethnicity, kinship, alliance, and enmity all played a part in shaping different Indian nations’ geographic dominion. Yet, no matter the political economy, all of them governed and defended bounded, sovereign domains.

Let us look briefly at those three case studies in Texas and the southern plains in order to get the conversation about Native borders going. It is often assumed that hunter-gatherers may be better understood for what they lacked as opposed to what they had, but they maintained clearly delineated ethnic domains defined by kinship and marriage. For hunter-gatherers such as Coahuilteco and Karankawa speakers, territories were often shared spaces of control within which certain groups maintained exclusive rights to collective ranges and resources. The allegiances among the groups meant that they joined together to hunt and to defend the lands they held in common. The boundaries of their territory were well established, known to all, and marked by natural sites such as rivers or bays and manmade phenomena such as watering holes, petroglyphs/pictographs, or painted trees. Trespass was a legal concept, and once Europeans arrived in the region they were subject to that charge.

Sedentary agriculturalists such as Caddos exercised control over a more expansive bordered domain made up of rings of settlement. Hunting territories manned and defended by small family groups in hunting lodges made up the outermost ring. Moving inward, the next ring was a space made up of farming homesteads surrounded by cultivated fields and small hamlets, each represented by a subchief. At the core, one found the ceremonial complex and primary township of the head political and religious Caddo leadership. To secure their domain Caddos had border control as well as passport and surveillance systems, and within their territory were internal boundaries between member nations.

For mobile groups such as Comanches and Apaches, raiding served geopolitical as well as economic purpose in aiding territorial expansion. Both groups evinced clear growth strategies by extending control over greater and greater subsistence zones. Their boundaries might move regularly, but that did not diminish the security of their borders; indeed, mobility was the key to border defense and resource management within extensive territories. Apaches and Comanches too marked their borders with landmarks, cairns, and trees made to grow in particular forms or directions.

Thus when Europeans arrived, all set to colonize the region, they found their border-making aspirations ran smack up against the border defense and border expansion of Indian nations. Spaniards and Frenchmen found no empty spaces into which to expand their empires; they had to seek Native acceptance and permission to build settlements, trading posts, and missions within recognized Indian domains. “Indian homelands brushed up against one another, their edges and peripheries creating zones of shared and contested indigenous dominion. The lines drawn between Indian polities more often than not took precedence over newer boundaries drawn between themselves and Europeans, even long after Spanish, French, and English arrival.”2

As it turns out, my scholarly concern with Indians’ borders, as outlined above, grew out of frustrations in the classroom teaching American history—frustration with two things particularly. One is the conceptual notion that as soon as Europeans put their first big toes on the American coast, all the Americas became a “borderland” up for grabs to the first European taker—a notion that denies Indian sovereignty, control of the land, and basic home field advantage. The second thing that set me off was the way in which our textbooks encourage this cockeyed vision of America with their maps.

Taking these two issues in turn, the concept of borderlands sometimes appears to be used alongside or in place of frontiers, but either way, when we map it out on the ground it remains essentially a European-defined space. In American history, borderlands, frontiers, hinterlands, and backcountry customarily refer to the edges and peripheries of European and Euro-American occupation and the limits of their invasion, expansion, conquest, and settlement, where Europeans and Euro-Americans confront Indians or rival European powers. Like frontiers, borderlands appear just beyond the reach or sphere of centralized power associated with imperial European governance. Like frontiers, borderlands are zones “in front” of the hinterlands of Euro-American settlement, or “in between” rival European settlements—think of the “Spanish borderlands” that are caught between the core of Latin America and the expansionary Anglo-American world. Either way, they are supposed to be untamed, unbounded wildernesses waiting to be taken in hand by civilized Euro-Americans.

Frontiers and borderlands are far from the imperial cores of France, Spain, Britain, and, later, the United States and by definition are absent of a monopoly of power or violence. So, on the one hand, these are spaces into which Euro-Americans go without the force of the state or military near at hand. Such conditions, by implication, are what make it possible for Indians to stand on equal ground, to negotiate, and to struggle for advantage. But, critically, Indians’ ability to stand their ground and to struggle for advantage has nothing to do with capabilities of their own; implicit to the idea of borderlands and frontiers is the assumption that Euro-Americans simply have not yet moved in or taken over, but, inevitably, they will. It is all part of a process, the first stage if you will, of inexorable conquest.

Borderlands are therefore spaces created by Europeans and Euro-Americans as they seek, explore, or expand into lands without borders. Borderlands appear where independent explorers, frontiersmen, and coureurs de bois launch themselves into the woods, in the process forging new paths for others—surveyors, settlers, and armies—to follow eventually. Or they develop where missionaries, licensed traders, and presidial soldiers move as representatives of church, state, or mercantile institutions at the forefront of official colonial projects. As Jeremy Adelman and Steve Aron outline, borderlands exist prior to European or Euro-American ability to claim, draw, and defend “real” imperial or national borders. The meeting of peoples creates frontiers, and the meeting of empires creates borderlands in their model. Most important, the only empires are European, and borders come into being only with European and Euro-American sovereignty.3 The problem here is that such an equation not only denies the existence of Indian borders but also credits the boundaries claimed by European empires and the United States with undue clarity.

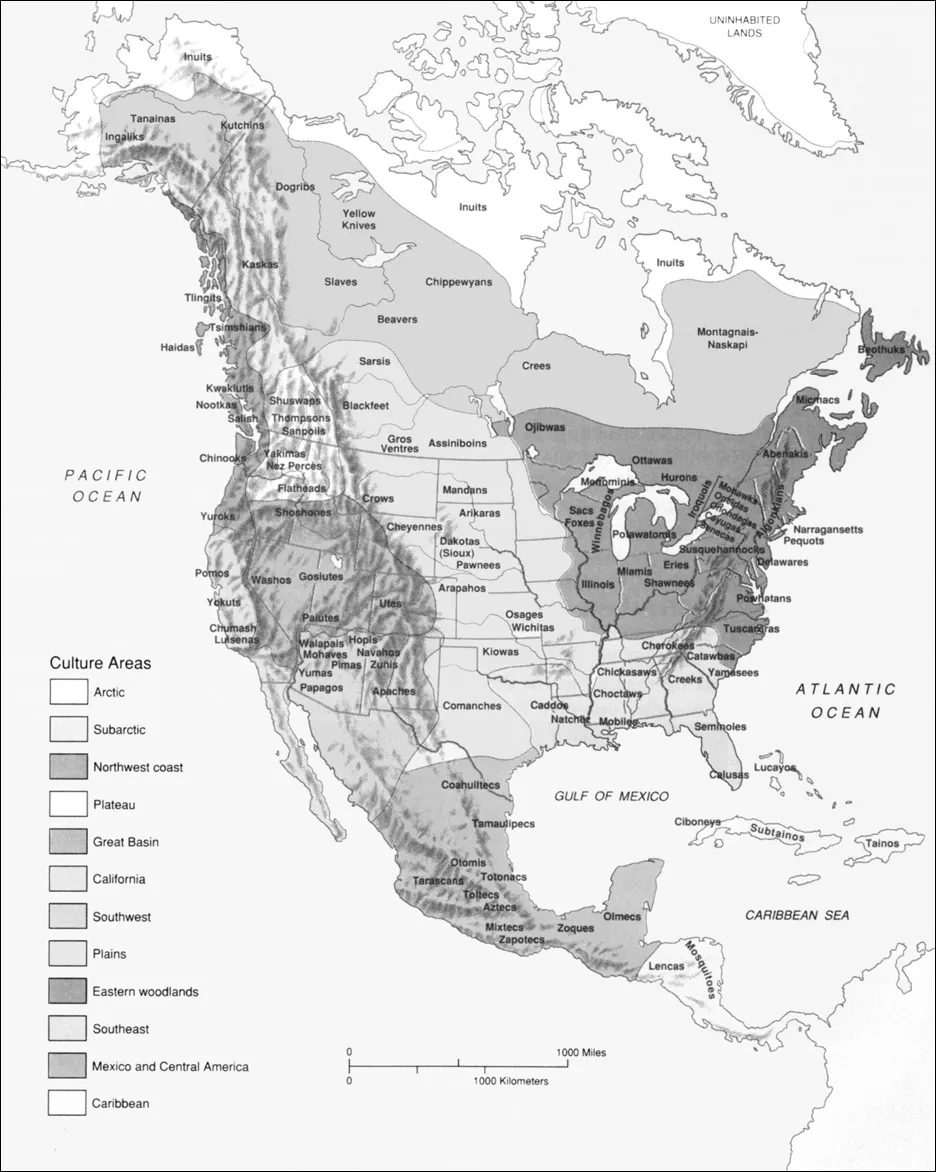

Meanwhile, whether intentionally or not, the maps in our textbooks contribute to an image of the Americas as a big blank, with no political divisions until Europeans and rival imperial colonizers arrive and begin to draw lines, divvying up the continent. When textbooks start with the obligatory section on pre-Columbian America, they feature maps that detail geographical divisions—Eastern Woodlands, Northwest Coast, Great Plains, Great Basin, Southwest, Subarctic, Arctic—or subsistence zones—agriculture, hunting, hunting-gathering, and fishing. Or, the maps detail the zones of different language families—Iroquoian, Muskogean, Siouan, Uto-Aztecan, Athabaskan, Salishan, Eskimo-Aleut, Algic. If and when the names of Indian peoples—never nations—appear in textbook maps, they float free of borders, hovering above the landscape with no defined boundaries to recognize the divisions of their territories. Thus, textbooks implicitly and explicitly tell our students that Indians had cultural, economic, and language zones of variation, but they had no named settlements or towns, no charted roads or highways, no territorial markers and, most important, no sovereign borders. We end up with a vision of North America ca. 1492 sparsely occupied by Indians living in tiny landless groups that were constantly on the move to hunt and gather.

FIGURE 1.1 “Culture Divisions among the Native Americans.” From Paul S. Boyer et al., vol. 1 of The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People, 8th ed. (Boston: Wadsworth, 2014), 1E. © 1990 Wadsworth, a part of Cengage Learning, Inc. Reproduced by permission, www.cengage.com/permissions.

Then, with European arrival, the map is wiped clean of wandering Indians or Native language culture zones, and in their places are Spanish, French, English, and Dutch “explorers” who tramp across a blank canvas, cutting through wilderness, discovering “unexplored” lands, with the only potential stumbling blocks along their paths being rivers, mountains, valleys, deserts and, for Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, the Grand Canyon. At this point, colored lines begin to appear marking the different routes of intrepid Europeans, with Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Hernando de Soto, Jacques Cartier, Samuel Champlain, Giovanni da Verrazzano, and later John Smith competing to cover greater distances and claim more territory for their rulers.

FIGURE 1.2 “The Spanish and French Invade North America, 1519–1565.” From Michael Schaller et al., vol. 1 of American Horizons: U.S. History in a Global Context (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 29. By permission of Oxford University Press, U.S.A.

Political borders first make an appearance in textbook maps of America only with the establishment of the British colonies, New France, New Netherlands, and New Spain—all of them “new” creations that rewrite historical spaces as European and, in so doing, deny the past of America’s indigenous populations. According to this cartographic vision, there are no “old” worlds in the Americas. Only then does America have towns for the first time—Quebec, Montreal, Boston, Jamestown, New Orleans, Santa Fe.

The most ubiquitous map design for this period of American history divides the continent into Spanish, English, and French territories—drawing borders for European claims far beyond the geographical reach of any imperial presence much less imperial control. If European rulers did indeed engage in a paper war of different colored spaces and imaginary borders during this period, our textbooks reprint the imperial fantasy. In stark contrast, Indian names may remain on the map, but they float free, with no moorings and no borders, subsumed under the authority of their presumptive new European overlords.

Taking this “anticipatory geography” to the extreme are the textbook maps that preordain the creation of the United States by backgrounding maps ...