![]()

Chapter 1: Join’d Together

The Anglo-Cherokee Alliance, 1730–1753

In 1729, an eccentric Scottish baronet named Sir Alexander Cuming sailed to Charles Town, the capital of the British colony of South Carolina.1 He was inspired by his wife, who dreamt that he would find wealth in America. Cuming spent five months in Charles Town, where he established a loan office and a mercantile firm. Then, he cajoled a coterie of traders into following him up the Cherokee Path to Indian country. His motives remain elusive to this day. Scholars have suggested he was slightly unbalanced.2

In the forty years before Cuming hatched his scheme, the French and British (and their North American allies) had clashed in two major wars. Tensions had flared again, and Cuming now inserted himself in the mix. He understood that a Franco-Cherokee alliance would devastate commercial profits and endanger British interests.3 With no credentials from the British government, he undertook an enterprise of incomprehensible hubris: he would convince Cherokees to declare their submission to the King of Great Britain and would forge an enduring Anglo-Cherokee military and commercial alliance. He would escort a delegation of Cherokees to tour England and formally seal the deal. The British Crown, Cuming hoped, would appoint him the first “minister to the Cherokees,” and he would become rich and famous.4 A member of the Royal Society, he would search for undiscovered medicinal roots and prospect for rocks and minerals. He might even lay the groundwork for a pharmaceutical or mining enterprise.5

The three-hundred-mile journey to Cherokee country carried Cuming toward several clusters of historically, culturally, and linguistically similar villages. Most villagers still identified strongly with their matrilineal clans. The seven Cherokee clans—Bird, Blue, Deer, Long Hair, Paint, Wild-Potato, and Wolf—corresponded at one point in time to seven “mother towns” where the Cherokee people originated.6Beyond clans and villages, there was no Cherokee nation-state. It existed only in the imagination of Cuming and other Britons.

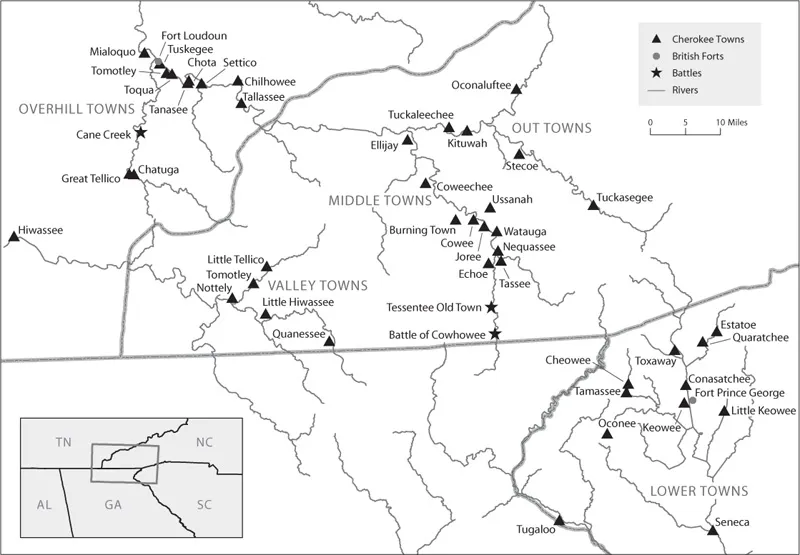

Some fifty settlements housed about three hundred inhabitants each, fifteen thousand Cherokees in all. Each village was autonomous. Geography, international relations, economic connections, and dialects grouped these villages in clusters identified by British traders as early as 1715: the Lower, Middle, Out, Valley, and Overhill Towns. Each settlement cluster was independent and, by virtue of proximity to different outsiders, each pursued different economic and foreign policies.7

The Cherokee Path headed northwest from Moncks Corner, about twenty miles northwest of Charles Town. It followed a road now beneath the waters of Lake Marion, then passed through Eutaw Springs, St. Matthews, and into present-day Cayce—“The Congarees.” From there it ran along the southwest bank of the Congaree River, then parallel to the Saluda River and through Saluda Old Town. It passed through the future site of Robert Gouedy’s trading post at Ninety Six (1751) and then through present-day Anderson, Pendleton, and Clemson before entering Keowee and the Lower Towns. These villages stood in the valleys of the Keowee and Tugaloo Rivers and on the headwaters of the Savannah in present Pickens and Oconee Counties, South Carolina. Prominent villages included Toxaway, Tamassee, Keowee, and Oconee. Villagers spoke the now-extinct Elati (Lower) dialect.8

From the Lower Towns, the trail then headed west, over mountains and across streams, approximately along present Highway 76. In present Clayton, Georgia, it forked. A northern fork headed to the Cherokee Middle Towns. They lay on the headwaters of the Little Tennessee River and along the Tuckasegee River, nestled among the Cowee and Balsam Mountains. Watauga, Joree, Ellijay, Cowee, and Echoe were among the larger Middle Towns, but political life centered on Nequassee (now spelled Nikwasi), in what is now Franklin, North Carolina.9

The Out Towns, the oldest of the Cherokee settlements, sat northeast of the Middle Towns, deep in the Smoky Mountains over Leatherman Gap. They lay off the main trade routes, unapproachable from the north and difficult to reach from the south. The Out Towns included Kituwah, Stecoe, Oconaluftee, Tuckaleetchee, and Tuckasegee. In time, the descendants of Out Townsmen and those who avoided removal in the nineteenth century would form the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Both the Middle and Out Towns spoke the Kituwah dialect; the Eastern Cherokee Nation and the United Keetoowah Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma still speak it today.10

MAP 1.1 Cherokee Villages in the Mid-Eighteenth Century

To the west of the fork at the Dividings in present Clayton, Georgia, and to the west of the Middle Towns, lay the Valley Towns, situated on the Hiwassee River and its tributaries. Hiwassee (or Great Hiwassee), renowned for its fierce warriors and its Natchez Indian inhabitants, was the chief village of the Valley. Other Valley Town settlements included Nottely and Tomotley.11

The same trail led northwest across the Unicoi Mountains to the Overhill Towns in present Monroe County, Tennessee. From there one path headed north to the Cherokee hunting ground in present Kentucky. Another followed the Blue Ridge and Shenandoah Valleys and connected the Overhills to western Virginia. Along the way, a road split off and led east to Williamsburg (sometimes spelled Williamsburgh), which lay 500 miles from the Overhills. The wide, verdant valleys along the Tellico River and the lower reaches of the Little Tennessee embraced villages such as Great Tellico, Chota, Tanasee (today spelled Tanasi), Toqua, Chatuga, Settico (Citico today), and Tallassee. Both the Overhills and the Valley spoke the same Atuli dialect. It later blended with Kituwah to form the Western dialect spoken by the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma.12

While the origins of the word “Cherokee” remain fuzzy, villagers called themselves “Tsalagi,” “Jalagi,” or “Tsaragi.” White traders commonly rendered the “ts” sound as “ch.” They thus applied the term “Charakee,” or “Cherokee” to the Lower Towns as they encountered those villages first, then applied the term to the people in each of the settlement clusters. The Spanish and French coming from the other direction—where the Creek Confederacy populated the area to the west—knew them as Chalaque or Chalagee.13 But for the English, the term “Cherokee,” sometimes spelled differently but with the same pronunciation, stuck.

On March 23, 1730, Sir Alexander burst into the Keowee townhouse with a cutlass at his side and two pistols in his hands. He told the Indians he would torch the building and kill those inside if any “endeavoured to make their Escape.” Cuming proclaimed himself an agent of King George II. At Cuming’s orders, or perhaps just to humor him, the Cherokees knelt in allegiance to the King. Cuming demanded that they send runners to invite the headmen of each village to meet him at Nequassee on April 3. Whether the Cherokees feared the economic consequences of ignoring Cuming’s bizarre display remains unclear. These tribal people may also have been swayed by the kilt-wearing Cuming’s use of Highland—tribal—garb.14

Cuming traveled through the Cherokee towns, shaking hands and memorizing names. In Great Tellico, he befriended a local leader named Moytoy. Then, Cuming and his entourage proceeded to the Middle Towns to Nequassee. Situated atop a fifteen-foot-high conical mound, that village’s townhouse was the center of village life. By Nequassee legend, Nunnehi, “the immortals,” lived under the mound and had come out to fight off an invading tribe, assisting local warriors. Centrally located within Cherokee country as a whole, the village of Nequassee lay in the heart of the Middle Towns. It was a “peace town,” a place of refuge, in which no living thing could be killed. Cherokee houses, orchards, and fields formed a picturesque panorama, with mountains in the backdrop. Here, on April 3, as Alexander Cuming ordered, Cherokees from each of the settlement clusters converged.15 “Such an Appearance as this, never was seen at any one Time before in that Country,” the adventurer wrote in his journal.16

The days that followed brought with them a series of ceremonies that English and Cherokee each viewed through culturally distinct lenses. Cherokees apparently assumed that the festivities were no more than mutual displays of friendship and peace. After a day of singing and dancing, Sir Alexander convinced the Cherokees to name Moytoy the “emperor” of the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokees, unaware of the meaning of that declaration, lifted the Scotsman onto Moytoy’s seat. They performed the Eagle Tail Dance for him and “stroak’d him with 13 Eagles Tails.” In a rousing speech, Sir Alexander “represented the great Power and Goodness of his Majesty King George.” He bade “all his Subjects” to “do whatever the great King ordered them.” When the Cherokees then knelt, he assumed their unflinching obedience to the Crown and to himself. The next day, Moytoy presented Cuming with the Crown of Tanasee—a wig of possum hair—“with five Eagles Tails and four Scalps of their Enemies,” imploring him to lay these items at George II’s feet. Cuming believed that the Cherokees had given him markers of sovereign power and status to bring back to Britain. However, this was a sign of friendship, not allegiance; none of the Cherokees interpreted the events as a ceremony of subjection.17

Sir Alexander then assembled a delegation of Cherokees to accompany him to England to prove that this had all happened and to conclude a treaty. He had already booked passage on the Fox, and it would leave in just a few weeks. Cuming targeted Ouconecaw, “a young warrior of Tannassy,” to join him. If the King knew “We were so poor & naked & so much Want of everything,” Cuming told the warrior, “He would take pity on our condition & would give us Some Cloaths.” The young Cherokee related later that his friend, the trader Eleazar Wiggan, “pressed” him that night. Finally, Ouconecaw relented and agreed to make the trip.18

Young Ouconecaw, or “White Owl,” was born in 1710. By some accounts, he was actually a captive from Canada. He went by many names, including the “young warrior of Tannassy” and Chuconnunta. By 1756, he answered to Attakullakulla, “the Little Carpenter.” He became one of the most influential but controversial Cherokees of all time. As a child, his Wolf Clan uncles trained him in the traditions of his people. He fished and fired blow darts along the Little Tennessee and its tributaries in the Cherokee Overhills. He was groomed for greatness.19 Young Attakullakulla witnessed a sequence of events that set the disparate peoples of the Southeast on a collision course.

By the time of Attakullakulla’s birth, Cherokee warriors had raided their neighbors and sold slaves to Charles Town for a generation. European diseases and the Indian slave trade depopulated the coastal tribes. The Tuscarora and Yamasee Wars of 1711 and 1715 took a further toll on the native peoples of eastern Carolina. The Indian slave trade declined, and the once-ready supply of deerskins and hunters near the coast evaporated. By 1715, the position of the Cherokees in the deerskin trade—and that of the Creek Confederacy and other nations to their south and west—changed dramatically.20 In 1711, trader Eleazar Wiggan had set up the first permanent trading houses among the Cherokees. By 1716, South Carolina established a public monopoly. Traders, many of them adventure-seeking Highland Scots, some of them exiled after the Jacobite Rebellion, rushed into the Cherokee country. South Carolina dominated the trade and its governor came to direct Anglo-Cherokee affairs. Charles Town was the largest and most navigable North American port below Philadelphia. From the Cherokee towns, traders sent their wares down the Savannah River and north by sea to Charles Town. Later they carried their trade overland as well.21

London merchants credited dealers in Charles Town, who in turn credited Indian traders with their season’s stock of goods. The traders advanced supplies to the Indians, whom they expected to repay them in peltries from the years’ hunt. In the winter, after several weeks of hunting, Cherokee men returned with deer. Women then cleaned and scraped the skins, since “dressed” skins fetched a higher price. In a time-consuming process, the skins were stretched on frames and dried, soaked, scraped, removed of hair, and treated with pulverized animal brains to create soft and supple leather. Cherokees also supplied ginseng root, snakeroot, and other plants to colonial markets for use as medicines. By the late spring or early summer, traders, with packhorsemen, servants, and slaves, arrived with an ever-expanding array of British goods. They brought English woolens in bright colors—strouds, duffels, striped shirts, coats, blankets, match-coats, hats, shirts, stockings, and anklets. They carried hoes, hatchets, knives, adzes, bells, kettles, scissors, and mirrors. They brought vermillion paint, guns, powder, bullets, gunflints, and tomahawks. The traders also delivered salt, liquor, and live poultry. And they established a permanent and visible presence in or near the Cherokee villages, marrying Indian women and introducing mixed-race offspring into Indian society.22

The deerskin trade was the vortex that sucked in the Cherokees. With gardens to tend, deer to hunt, and skins to tan, little time remained to manufacture household items and clothing. In these changed circumstances, the Cherokees needed British goods to replace things they no longer made themselves. But there were new items as well, readily incorporated into daily life. The Cherokees took pride in personal appearance, and the array of available merchandise was mesmerizing. Beholden to the merchants on the coast, traders kept the Indians in perpetual debt, or close to it.23 Thus they became more dependent on manufactured items. By 1753, Skiagunsta of Keowee, then the most prominent warrior in the Lower Towns, claimed that “every necessary Thing in Life”—clothes, guns, blankets, and more—“we must have from the white People.” He continued, admitting, “my People … cannot live independent of the English.”24

By the 1750s, the Cherokee were not just dependent upon European trade goods. They were embroiled in a territorial dispute with their neighbors to the south: the loose confederacy of Indian peoples known as the Creeks. They were also in the middle of the rivalry between France and Brita...